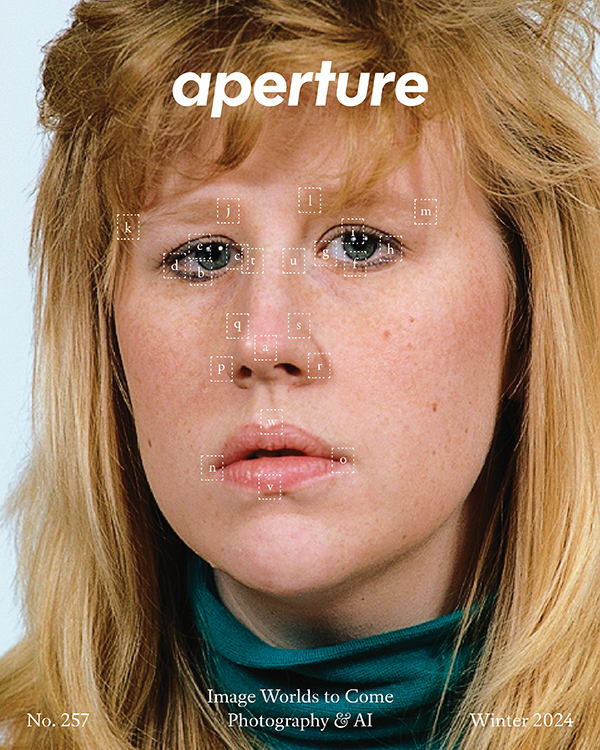

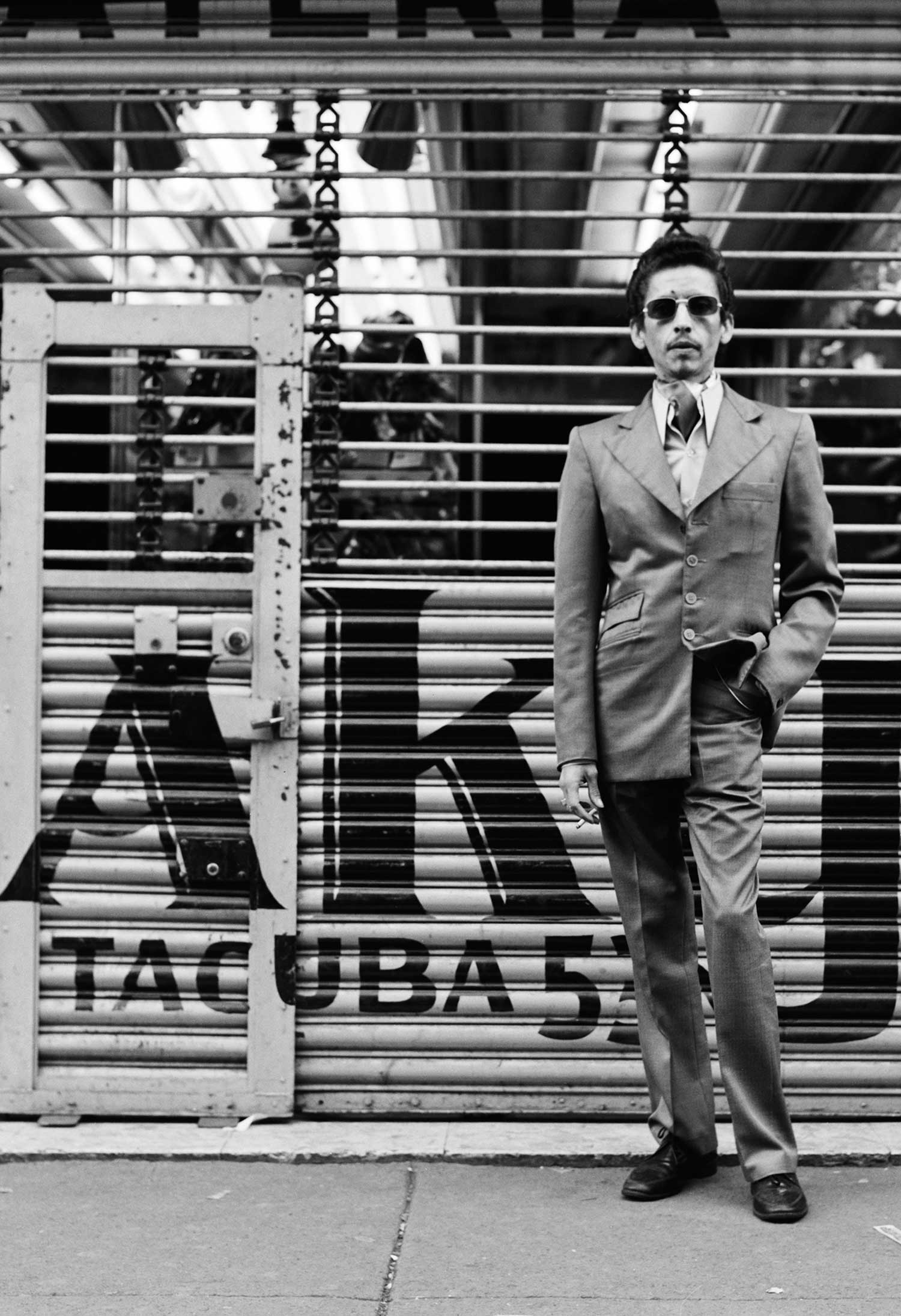

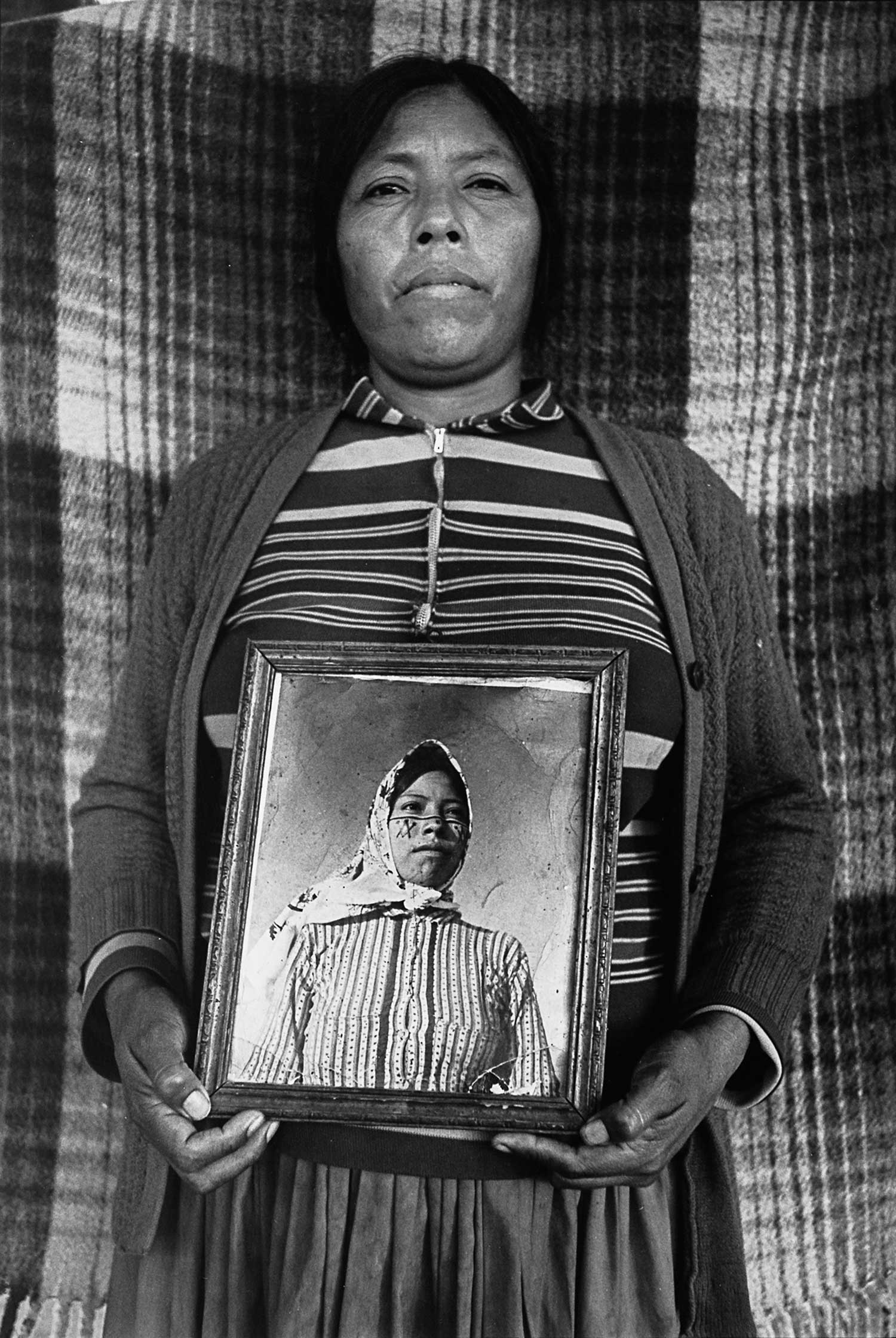

Graciela Iturbide’s Dreams and Visions

For more than fifty years, Graciela Iturbide, recognized today as the greatest living photographer in Latin America, has envisioned the diversity of life in her native Mexico. Her lyrical, black-and-white images of street scenes in Mexico City, of Seri women in the Sonoran Desert, of political rallies in Juchitán, and of details inside Frida Kahlo’s bathroom are revered throughout the world. At the age of twenty-seven, aspiring to be a filmmaker, she enrolled in a university class with the maestro of modern Mexican photography, Manuel Álvarez Bravo. The experience was formative. “More than being my teacher of photography,” she recalls, “Don Manuel taught me about life.”

Earlier this year, the editor and publisher Ramón Reverté visited Iturbide at her home in the Mexico City neighborhood of Coyoacán. One wall of her living room is lined with soaring shelves full of beloved photography books. In her studio located across the street—built by her son Mauricio Rocha, a noted architect—she keeps altars of objects and books that belonged to Álvarez Bravo and Josef Koudelka. At the time of Reverté’s visit, Iturbide had recently opened two major solo exhibitions, one at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and another at the Palacio de Cultura Citibanamex, in Mexico City’s historic center, which drew hundreds of thousands of visitors.

Here, Iturbide speaks intimately about her beginnings, her passion for photography and books, her long-standing interest in Mexico’s Indigenous cultures, and her favorite photographers, including Álvarez Bravo, who has been, as she says, “her guru.” On one occasion, Iturbide told Álvarez Bravo that she was traveling to Paris to visit museums. “But why,” he replied, “if you can see it all in books!” Iturbide, a relentless reader, took his advice, but only partly: she has never stopped traveling.

Courtesy the artist

Ramón Reverté: I’d like to ask about the beginning of your career—I’m sure you’ve probably gotten the same question a thousand times—how did you come to photography? And I’m curious whether from an early age you enjoyed painting and photography, or is it an interest that was ignited as a result of your meeting Manuel Álvarez Bravo?

Graciela Iturbide: In my family, there wasn’t an affinity for any of those things. I wanted to be a writer from a young age. My father, who was very conservative, wouldn’t let me attend university because women were supposed to stay at home. I married very young. I quickly had three children. I wanted to study philosophy and literature, but I couldn’t because, with three children, I had no time.

At an early age, I had a camera, and I took photographs because my father was an amateur photographer. I loved to go into his closet and steal his photographs, which led to various punishments, but my father should have been proud I was stealing his photographs.

In 1969, when I was already married and twenty-seven years old, I heard on the radio that there was a university where you could study film, and I enrolled. It was very easy to get admitted; everyone got in because it was when the film school was just getting started. That’s where I met Manuel Álvarez Bravo, who was giving photography classes. I had the book he had published during the 1968 Olympics in Mexico and brought it to him so he could sign it. I asked if I could take his classes, and he said yes. No one went to his classes because everyone wanted to be film directors. After two days, he said, “Listen, I’d like you to be my achichincle,” and I said, “Of course.” An achichincle in Mexico is the person who assists the construction worker and does a bit of everything.

That’s how my life changed. We spoke a lot about painting. We listened to a lot of music. It was my salvation in life because he had a very different way of thinking than my family. On one occasion, he told me, “You know what, Graciela, divorces help because one can start anew.” It was like he was opening me to life. Within a year, I was divorced, without any struggle, without any issue.

Courtesy the artist

Reverté: Tell me about your parents. Did you go to exhibitions when you were little?

Iturbide: Not so much to exhibitions, but we went to concerts, to the opera, to musical things. Sometimes my father would take us to the Cervantino Festival. I was very young then and was somewhat interested in cultural things. My parents’ parents had haciendas. With the revolution, and then under President Lázaro Cárdenas, they lost everything. My father had to work from a young age to support his family. At the age of sixteen, he started working in Oaxaca with the archaeologist Alfonso Caso, strangely enough, as his assistant. He never had a formal profession. My mother played piano recitals when she was young, and she loved classical music. She also drew. She was more sensitive to those kinds of things. But I wouldn’t say it was a cultured family. It was a bourgeois family.

Reverté: When you decided to study film, was it because you liked film, or because you saw some kind of escape? Was it a conscious decision?

Iturbide: Yes, because I wanted to. I told myself, In film, there is a script, and I want to study literature, so I might as well study film and see what I can do from there. I did it out of my need to study something because I had never been allowed to. It was an urgent need within myself.

Reverté: So photography wasn’t an interest of yours at that time?

Iturbide: I took photographs as a child because my father gave me a camera when I was eleven years old. But I took photographs of things like churches, from the bottom up, stranger things than my cousins and siblings photographed. I always saw my father taking photographs, and he did a bit of film, but just as a hobby.

Courtesy the artist

Reverté: So it’s really Don Manuel who introduced you to the world of photography?

Iturbide: More than being my teacher of photography, Don Manuel taught me about life. I was already developing my own film because I had taken some photography classes before taking lessons with Manuel. So one time I asked him, “Maestro, how do you properly develop a roll of black-and-white film?” And he responded, “You know, Graciela, go to the photography store, buy yourself a roll of film, read the instructions, and that’s how you do it.” He never told me whether my photographs were good or bad. Never. But he spoke to me a lot about painting. He spoke to me about literature. We listened to opera in the afternoons.

He made me see life in a different way than I had lived it as a child. When I lived with the father of my children, who was a more liberal man than others I had known, it also helped a bit in my development. In my time, it was unlikely for husbands to say, “Yes, yes, of course, go study.” It wasn’t very easy.

Reverté: How long were you working with Don Manuel?

Iturbide: I worked with Don Manuel for about two years. But I stayed near him all my life, that’s why I live here. When I separated from my partner, I came to live here [the Coyoacán neighborhood of Mexico City] because Álvarez Bravo told me, “They’re selling a little plot of land over there, Graciela. Come here to Coyoacán.”

Courtesy the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Reverté: Photography wasn’t an easy path to making a living.

Iturbide: I’ve had money, I’ve had no money, but when I didn’t have money, there were rolls of film in my refrigerator. I’ve always been taking pictures. At the very beginning, and when I got divorced, the only work I had was for hire for magazines like Mundo médico (Medical world) and Médico moderno (Modern doctor) to go photograph operations.

Reverté: And what did you photograph?

Iturbide: Births. Once I won an award for a cover that I shot. They paid me monthly. I didn’t have to be there the whole time, only when they commissioned things. It’s the only work I’ve ever had for hire, and I loved it.

Reverté: What was your first contact with the photography world? Was it at the INI [National Institute of Indigenous Peoples] that you first began?

Iturbide: I only did a project with the ethnographic archive at the INI. They made various films and published seven books about this archive under the direction of Pablo Ortíz Monasterio. It was my job to go to the desert with the Seri, and I was fascinated.

Reverté: The first exhibition you had was in Mexico, and then it traveled to New York.

Iturbide: My first exhibition was at the Orozco Gallery with Paulina Lavista and Colette Álvarez Urbajtel. And then it traveled to New York, with a photographer named Larry Siegel, who had been my teacher here in Mexico before I went to study with Álvarez Bravo. He was the director of the gallery in New York.

Reverté: So that exhibition had nothing to do with Don Manuel?

Iturbide: Yes, that exhibition came about thanks to Manuel because Larry spoke with him and Manuel decided that it should be three women: Paulina Lavista, Colette, and me. After that, I started to have solo exhibitions.

Courtesy the artist

Reverté: How did you manage to maintain a family at such a complicated time, in addition to being a woman on your own, in that era in Mexico, with three children?

Iturbide: At the beginning, I had the help of my husband, then I worked for Médico moderno, and then I worked taking photographs of people who asked me to take photographs.

Reverté: Portraits?

Iturbide: Lots of portraits, even weddings. I managed. I made money, but I never stopped taking my own photographs. I loved going to the country to be with Álvarez Bravo.

Reverté: You continually saw Manuel Álvarez Bravo?

Iturbide: Always. Until the end. I always went to see him to speak with him, to listen to music. The thing is that I didn’t want to be his assistant anymore because I didn’t want him to influence me. I had to cut the umbilical cord.

Reverté: Even though Don Manuel’s influence is present in your work, in the most positive sense, you had a personality all your own in your photography from the very beginning. What is it that truly moves you to take photographs? If you go somewhere now, what motivates you? What is it you want to photograph immediately?

Iturbide: It’s never clear to me what I want to photograph. I always go out walking, even when I’m asked to go photograph something in particular. Surprise is what gets me to pull the trigger on the camera. If I say, “Ay! What a wonder!”—then I press the trigger.

Courtesy the artist

Reverté: Do you take lots of photographs?

Iturbide: A normal amount. I’m not like the people who came from Magnum. When I took them to Manuel’s house, they saw a dog on the rooftop and started to take a ton of photographs. Manuel always said to me, “Chaca chaca chaca chaca, why so much junk, Graciela? For what?” I learned a different way of taking photographs from Álvarez Bravo, because he always took one or two shots. If, by chance, he took two, it was already too many. In my case, if I come across something and I like it, I could even take three or four photographs, but I’m not a compulsive photographer. Sometimes I’d take more than one shot in case the negative gets scratched. I always took photographs calmly and enthusiastically and with surprise.

Reverté: If I were to go with you to photograph for two days in Oaxaca, what would the process be like?

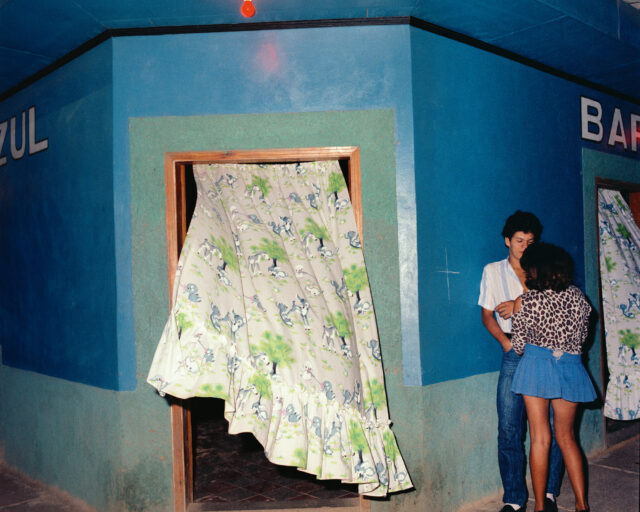

Iturbide: I went to these villages with my camera so that people would know that I was a photographer, and I lived with them, which created solidarity. If I go to a festival where photography is allowed, then I take photographs because it’s allowed. If I see that it isn’t allowed, that people don’t want me to take photographs, I don’t. I don’t have a telephoto lens, nor a tripod, nor flash. It’s how I’ve always worked, with a handheld camera but always with people’s complicity. Sometimes, people ask me to take their photographs, like with Magnolia [the iconic photograph from the 1979–89 series Juchitán de las Mujeres]. I was at a cantina, and she was there, and she saw me with my camera and said, “Ay, ay, my love, take my photo.” I went upstairs with him, or with her, to the room, he got dressed, he made himself up, and I went on taking photographs as he wished, exactly as he wished.

Reverté: It’s obvious that you share empathy with people.

Iturbide: Yes, it’s beautiful when people ask you to take their photograph. When I go to Juchitán or when I am with the Seri, for me they are not “the other” because they also come to visit me at my house, the same with the Mayo [the people of Sinaloa] as with the Juchiteco. These are people of my country, just like me.

And yes, I have a capacity to feel empathy. I try not to hurt people. That’s why I just have a normal lens that allows me to come close to people, and somehow they accept me even if I don’t ask permission. In some way, with the camera, I am asking. There is an implicit permission.

To continue reading, buy Aperture issue 236, “Mexico City,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

This interview was translated from the Spanish by Elianna Kan.