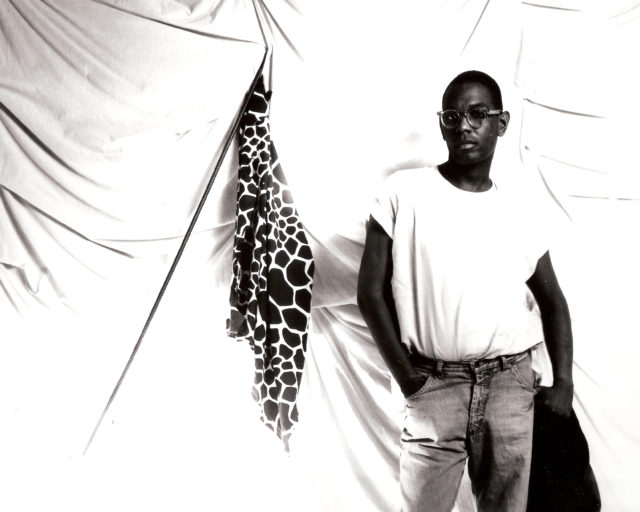

Ming Smith, David Murray in the Wings, Padua, Italy, 1978

The photography of Ming Smith has haunted the international art form like a specter for over four decades. Artist Arthur Jafa has been on record as Smith’s most enthusiastic hype man for half that time, routinely referring to her as the greatest of African American photographers, if not of contemporary art photographers in general. In 2017, he put his admiration and advocacy on “front street,” per the vernacular, by including a survey of Smith’s work in his epic traveling “solo” show A Series of Utterly Improbable, Yet Extraordinary Renditions, an exhibition which debuted at London’s Serpentine Galleries and has since toured several European cities, including Berlin, Prague, and Stockholm.

Smith was born in Detroit and raised in Columbus, Ohio; her father was a dedicated amateur photographer. She began her own photographic journey into the art world shortly after graduating from Howard University and moving to New York to work as a model. She quickly garnered a series of significant “firsts”: the only female member of the Kamoinge Workshop for Black photographers founded by Roy DeCarava, and the first Black woman photographer to have her work purchased for MoMA’s permanent collection. Smith exhibited sporadically in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, but jazz fans internationally were made aware of her work via over a dozen album covers for recordings by her former husband, saxophonist David Murray, on the Italian label Black Saint and the Japanese imprint DIW. The selections were an eclectic mix of self-portraits, jazz subjects, and more oblique personal work.

The work that has most inspired and intrigued Jafa has been images in which Smith foregrounds blurred figures of Black folk. In his book Black and Blur (2017), critical theorist Fred Moten (Jafa’s good friend and intellectual confidant) provides myriad novel ways of thinking about blurring in contemporary Black art-making as an artistic and political strategy—one frequently bent on poetically illuminating, through sublimation and subterfuge, the impact of anti-Black violence (historic and systemic) on post-traumatic Black subjects, Black interiors, and Black communities.

Smith’s strategic deployment of blurring in rendering her varied Black subjects and communities is seen by Jafa as an act of love and loving protection from predation by a policing white gaze. It is also testament to Smith’s creative affinity for the freedom-seeking music produced by her generation of jazz artists—that revolutionary group of outliers from California, the Midwest, and New Haven, Connecticut, who collectively transformed the music’s sonics and expanse of conceptual vision in late-1970s New York. These musicians embraced Smith as a creative compatriot and fellow traveler and she, in turn, immortalized them in her artful and liminal documentation of their effigies and performances.

In our conversation, Jafa opens an initial emphasis on Smith’s musicality and visual sonorities into a more complicated discussion about her work’s explorations of what we’d call the “maroon fugitivity” of Black postmodernity and post-traumatic modern Black folk.

Greg Tate: Brother J!

Arthur Jafa: I’m here, I’m here, I’m here.

Tate: We’re talking about the presence of music and sound in Ming’s work.

Jafa: [hums a refrain]

Tate: That series of album covers that Ming did for David Murray in the 1980s, was that your first exposure to her work?

Jafa: Well, no, it actually wasn’t. The first time I saw her work was in The Black Photographers Annual, that featured the work of several members of the Kamoinge group. In each issue, everybody would get one or two photos; then maybe they would have three or four photographers who would get a bit more of an extended space, like a little portfolio section. If I remember correctly, Ming had five or six photos in one issue. So that was my first exposure to her work, and I thought it was pretty amazing.

Tate: It had an impact immediately.

Jafa: Yeah, definitely. My ongoing obsession at the time was like, Where are the photos of Black cultural modes? I knew Ming was great. No doubt about that. But being great and being somehow bound up with a quest for a thing—they would call it a “mother tongue”—they’re not exactly the same thing; Black artists can be great without the thing being inherently Black. But Ming’s thing was super Black. She definitely made an indelible impression on me. She was the standout of The Black Photographers Annual, and not just of one volume, but of the entire series. Later, when I moved New York, I became aware of the David Murray album covers and stuff like Home [David Murray, 1982].

Tate: What is the relationship between Black visuality and Black musicality, in your critical sense? What’s the path that binds the two?

Jafa: I was always interested in a certain kind of transformative proximity. Meaning, I was fascinated by the pressure that the music put on the visualizations which, more often than not, had to do with album covers at that point. But there was a pressure the music put on the visualization, to come up with something that seemed simpatico or consistent with the nature of the music.

There’s a long history of jazz photography that’s quite amazing, like many of the Blue Note covers and things like this, that are very distinctive, to say the least. But nevertheless, much of that photography, even though I think it’s good photography, didn’t necessarily feel like it was uniquely Black in its modalities, in its expressive and technical modalities. You know what I mean? So the first time that I saw work that I thought actually was tapping into something was, like I said, album covers. And particularly things that Ming shot, and at the same time, I sort of stumbled on Hart Leroy Bibbs [journalist and photographer from Kansas City, Missouri; 1930–1994]. Bibbs, in some ways, may be the predecessor. His work seemed to be preoccupied with the photography of jazz and Black music performing. Then, the other person one would have to reference would be Roy DeCarava, who had, as a subset of his larger body of work, jazz photography. In particular, there are some really incredible pictures of Coltrane and his ensemble.

From the beginning, from the inception of jazz, you had identifiable musical phrases, songs, melodies, things like that. Then, when you get to bebop, you start to feel an abstract relationship to melody and figures. But then you start to get to free jazz and you start talking about a blurred figure, a figure that isn’t so discretely defined as a figure against a background, then you start talking about the slow shutter speed. In visual terms, you would start with Roy DeCarava. You can see it from his crisply defined but moody figures. In his photos of Trane, there is a kind of impressionism and expressionism that starts to enter into the photography. There’s DeCarava’s John Coltrane on Soprano [1963]. The combination of low light levels, like you would have in clubs, not being able to use flashes, and having to open up the shutter speed, together with people’s movements being more agitated, would generate some of these sort of blurred figures that I’m talking about.

I don’t know if DeCarava went into these spaces and said, “Hey, I’m going to slow my shutter down and create this effect that’s going to seem more commensurate with the music,” or if it just was a technical solution. But one thing that becomes really clear is that Ming, Hart Leroy Bibbs—and I would also put Spencer Richards in this group of photographers—realized that there was an equivalency between this music flow and these blurred figures, which erases much of the distinction in between foreground and background.

Tate: Well, part of the rhetoric around free jazz is that it’s cosmic energy music, music concerned with invoking and evoking spirit possession. The kind of vibratory resonance. Anyone who’s been to a really electrifying performance of the freer music knows that it does open up a heightened sense of the optical as well as the auditory, and expands our sense of the spiritual and the soulful. So we definitely see a connection between that idea of energy music and Ming’s work that has the blur, has a similar kind of vibratory harmonics going on. How would you relate that to what’s going on in her nonmusic practice?

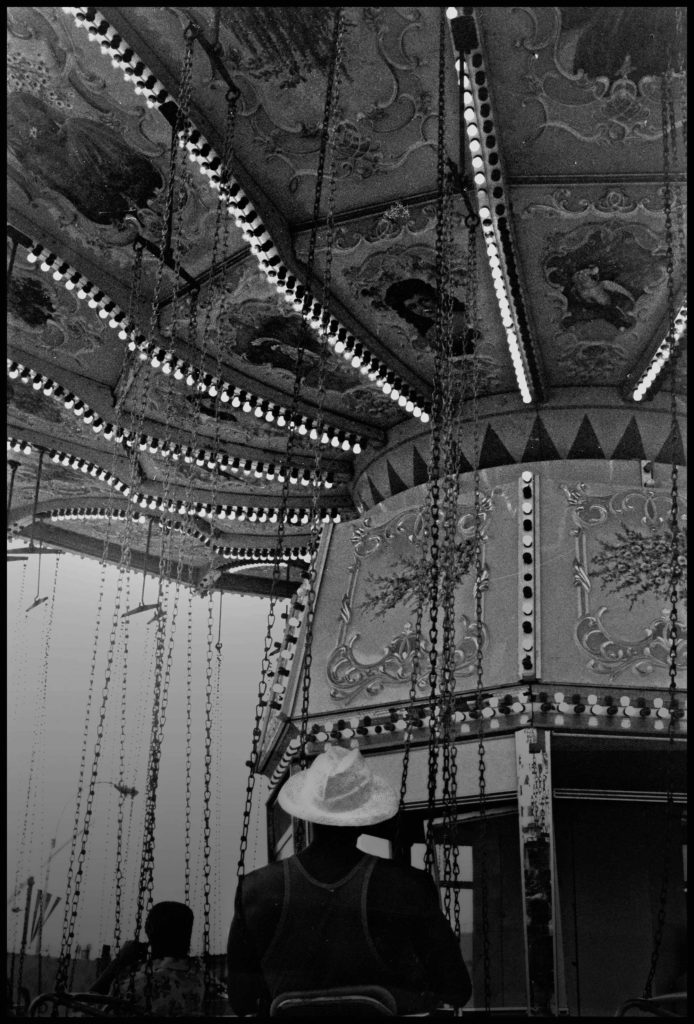

Jafa: The two places that you see this pronounced vibratory quality are in the photos, like we said, of musical figures, and the other place would be in the photography of churches. In both instances, you’re talking about a kind of heightened experience. You’re also talking about lowlight situations, or at least situations where a flash would be inappropriate. Versus, one could be “discreet” in a pool hall or something like that, but it would have more to do with being discreet than the appropriateness in a cultural sense, in the appropriateness of a flash. Certainly not outside, or when people are posing.

The typical Western visual dynamic has to do with figure and ground relationships. Like, what is the figure? What is the subject? What is the object? What is the background? What is the foreground? There’s really two ways you can get at blurring the distinction between the foreground and the background. One way is the shutter speed, which means that the figure itself is being smeared, in a sense, on the negative, or the target. And the other way that you can get at it is tonally. Basically, the foreground figure is high-lit. You know what I mean? It’s generally edged by the light in a certain kind of way. In the most elemental sense, it’s what you see in classic Hollywood cinema—the subject is keyed by the light. Even if it’s an interior, the sunlight is hitting their face, and the background will fall off behind them. So they actually are brighter than the background.

If you talk about Ming’s work outside of the church and outside of the music thing, what you see her doing is something akin to what DeCarava does, with these flattened midtones. Or everything is in a high key. She erases or destroys this background-foreground relationship by making the figure or the subject not brighter than the background. Some of Ming’s most incredible photos—I’m thinking of things like in the telephone booth in Harlem—they’re striking precisely because of that. In many instances, her figures are silhouettes. There’s a heightened sense of shape. If you’re going to have a figure that’s not brighter than the background, things like shape become one of the primary tools that’s being utilized to create formal complexity, to create differentiation in the visual field.

Even in some of Ming’s Sun Ra pictures, what you actually see is a combination of these two techniques. You see the blur and, as in DeCarava, these flattened midtones. What’s unique about Ming is her ability to use this shutter thing to erase much of the distinction of the boundaries or the edge between the figure and the background, but at the same time, have it be very precise in this articulation of form. It’s a very, very, very difficult thing to do, because as soon as you lower the shutter speed, you reduce the sharpness of the figure. Man, it’s crazy that she can actually do that so consistently, know what I mean? It’s one of the great mysteries of her photography that I’ve always been curious about—what her actual settings are. And then, even when you have the shutter speed, it’s not just the figure moving. It’s like, how much motion you induce to the figure by the camera shaking, to a certain degree. Which is another way that the shutter speed winds up manifesting itself.

Now the other thing, which I think goes even further to this question, is completely tethered to insights taken from Robert Farris Thompson’s African Art in Motion [1974]. Thompson talks about the classic natal context in which African artifacts are being exhibited. In the West, where the object has no agency, it is on a pedestal; the eye can move around the object, which is static. The object is frozen, in a sense. It has no ability to move or to relocate itself in space, he says. In the classic or the natal African traditional context, that artifact moves around the viewer as much as the viewer moves around the artifact. And that dual movement produces a blur. You don’t want to have one static thing, like a kind of open appraisal. That’s what the shutter speed is, the length of appraisal, the time in which one will actually look at a thing. And if you extend that length of time and you move, you’re going to get a blur. Then, in the church or the performance, there’s the motion that’s being induced by the actual movement of her hands—meaning not holding the camera perfectly static. That’s in space-time terms too, like a target that’s distended. It’s the classic thing of people posing for a photo. You always say, “Be perfectly still.” Right? Ming’s technique is based on a complete disavowal of both of the classic tenets of the photographic capture. And I think that lines up perfectly with the deep philosophical implications of this inverted or subverted figure, foreground-background, figure object relationship that Robert Farris Thompson articulates in African Art in Motion. So these things are not accidental.

Tate: When you were talking about shapes and silhouettes, I thought of that great Amiri Baraka line, “the shapes in the darkness had histories,” from his book Tales [1967]. With Ming and Baraka, you recognize this quest into the underground of the Black working-class environment. They both have created these magnificent bodies of work that put you inside of a particular kind of Black populated darkness, an Abyssinian field of communal interaction. There’s been hundreds of Black photographers who have shot in the hood. But there’s something extraordinary that Baraka and Ming pull out of their intimate engagement with what I call “real Black life.” It’s so rarefied.

Jafa: They’re both more into the dark places. There is a direct correlation between this idea of darkness, just like literal darkness—in technical terms—and how your eyes adjust to the darkness at a certain point. And that darkness is both figurative and literal at the same time.

The one photography book that Baraka was involved with is In Our Terribleness [1970], by Fundi, who was also in The Black Photographers Annual. And one of the things that’s really distinct about his work, too, is the darkness; and the darkness that he achieves is not just from the light level being down, but it’s also completely bound up with this flattened tonal thing between the foreground and the background. You also see that in Carrie Mae Weems’s work, the way she’s playing with the figure against the dark ground.

Some of the way I term it is “super bad,” like when people shoot things that are not just bad, like in technical terms, but they’re like unrepentantly bad! And the technical badness starts to function on the meta level. It’s almost like the Black man’s heaven is the white man’s hell—some shit like that. It’s like when James Brown said, “I’m bad, I’m super bad,” this whole idea that we’re going to invert these values. It’s this interconnected space where the metaphoric becomes literal, becomes a new point of reference to any kind of norm. So the whole question becomes: what is the default status for Blackness? And it, of course, is darkness. Because Blackness is not the same thing as Darkness, but Blackness as it’s structured in the West is inherently going to be always in proximity to Darkness, because Darkness functions as all kinds of things, like positively and negatively. It functions as black. Deprivation. Not having power. But it also functions as stealthiness. Doing things under the cover of darkness. You don’t really think of runaway slaves as running away in the day. You think of them as running away in the night. Steal away, steal away; you think of people stealing away in the night.

Tate: Under cover of darkness.

Jafa: Yes, under cover of darkness, exactly. As soon as you make a photograph that starts foregrounding things like darkness, it’s inherently bound up with issues of self-determinacy and of freedom.

Tate: I remember what the photographer Jules Allen was saying about Ming; this was the first aesthetic appreciation of her I ever heard from anybody. He just said, “She’s the best of us.” I know you certainly concur with that. But I’m wondering, if we want to talk about aesthetic benchmarks established by Black artists, what’s going on in her work that generates an aspirational response? What’s she doing that’s so singular and powerful?

Jafa: Her capacity to control the dual technical strategies and abnormal technical strategy of slow shutter speed, and the flattened tonal range, to erase the typical relationships between figure and background, foreground and background, are unparalleled.

Tate: I’ve heard you talk about it in terms of Black cinematography, this whole notion of a “God particle.” I’m also asking, what is it about her relationship to Black subjects in the visual fields that Black people occupy in the world that is just so potent and so poignant? Let’s talk about the existential or the emotional aspects of what her photographs generate for you.

Jafa: I mean, what you see in the work, which is what you see so often in the works of any Black artist—let’s talk about music, as an example. That field has been so defined, so structured by Black phonic expressivity, that even the most casual Black-produced music is doing certain kinds of things that Black people take for granted, in terms of them affirming what we consider beautiful. And then there’s people, like an Aretha, or an Albert Ayler, or Jimi Hendrix, who seem to go that further distance—they’re always bound up with the limits to which they are willing to go to affirm aspects of Black sonic beauty or taste, which would be considered, at best, on the margins of appreciation in other musical modalities. Vibrato. Undertone. Overtone. Things like this. It’s on the edge of those things. In other words, it becomes like the space in which a Black person in the space of other values, or maybe dominant values, nevertheless will hold the line in foregrounding schemes in their work.

In photography, that thing which is taken for granted in the musical arena, around which we have basically structured ourselves, is much less prevalent. So, when I talk about these foregrounds, backgrounds, and things, that’s the gist of it. Nobody else has gone as far as Ming in terms of her commitment to doing it. The existential dimensions have to do with the way in which the technical parameters of what she’s doing are, in fact, structured by a commitment to being in those spaces that Black people occupy. The spaces that are underlit. And because they are underlit, and because they are secret spaces and things like this, they require the technical approaches to be aligned with those spaces.

So, as opposed to saying, “People, come outside in the sun so I can photograph you,” it’s like, “No, I’m going to go into these dark spaces with you.” And the technique that would conventionally be considered what you would have to do to rescue the photography, to make a suitable picture, is thwarted. It’s like saying, “No, I’m going to put the pressure on myself of actually coming to where Black people are,” rather than bringing Black people into what would be considered a technically appropriate relationship to the photography.

You see a lot of consequences of this commitment to going into the spaces that Black people occupy, or are forced to occupy, or left to occupy. For example, we know one of the more egregious aspects of the very mechanism itself, photography, is surveillance. Right? Black people get tight around photos, in a certain respect, because they are being surveilled, and there’s always a danger that the photograph can be used as evidence against you in some fashion. But as soon as you say, “I’m going to go into the spaces in which Black people feel comfortable that they’re not being surveilled”—meaning dark spaces, underground spaces, spaces in the woods—the photographer is now introducing into that space the instrument par excellence of surveillance. What that means, then, is you have to be willing to embrace techniques that, in a sense, void the ability of the photograph to function as evidence. In many of Ming’s photos, you can’t identify anybody.

Tate: Photographer as a predator for The State.

Jafa: Exactly. You can’t identify anybody in them. They couldn’t be used in a court of law, because you can’t make out people’s faces! What you’re left with are things like the line of a person’s body, a person’s postural semantics, things like that, which cannot be used as evidence. You can’t be like, “That person stands like X, Y, and Z,” you know what I mean, when you can’t really see who it is. It’s amazing how in a large percentage of Ming’s photos, you can’t identify a single person!

Tate: It’s this rendering of evidence of things unseen.

Jafa: Absolutely.

Tate: They operate in this meta-dimension. Some call it “Blacknuss.”

Jafa: Or, as you say, in planes and shadows. It’s not true of all of her pictures. But I mean, Male Nude [1977]. The person’s back is to the camera. And then it’s quite literally a figure against a background, and it looks a little dark. And not because the person is Black. I’m saying the tones are pressed together. Or Farewell to Alvin Ailey Ailey (Mother) [1989], you can see those people’s faces, but that would have something to do with the nature of it. That’s a more straightforward document of that event. But then you go to Dakar Roadside with Figures [1972]—you can’t use that to say who that person is. Not at all. And the same with Family Free Time in the Park [1982]—they’re silhouettes. You go to What’s It All About? [1976]—that kid is on the cusp of silhouette. You can certainly identify him there. But he’s on the cusp of silhouette.

These are pictures that I would say—like God, Mary, Jesus [1991]—that I think typically get presented in Ming’s work as evidence that she can take a decent photo. They look more conventionally like the photojournalism that we associate with Black photography, which I think most people do. But when you come to Invisible Man, Somewhere, Everywhere [1991], which is one of her masterpieces, you can’t fuckin’ identify nobody in that. It’s really interesting, the tension in so many of these photos between saying it’s X, Y, and Z, that you can’t identify the person. It’s not clear of all of them. But I’m saying it’s something you see quite a bit of. It’s a high percentage of her photos. Or Cadillac Man [1991]. These are clearly pictures that are about how bodies occupy space. But they don’t identify who the bodies are.

All photographs courtesy the artist

Tate: Ming has a romance with the mystery of Black people as shadows moving in a shadow world.

Jafa: And, I would say, she is very invested in Black fugitivity, the fugitivity of Black people.

Tate: A fugitivity that’s not bound up with escape but a kind of self-illumination.

Jafa: A Yeah, totally. Circular breathing. It’s like this whole question of shape, man. Shape and silhouette. How pronounced it is. She can do all kinds of things. But this is something she does that hardly anybody else can do on this level. I don’t know another photographer who can do work in this modality with this level of specificity and precision. Look at Abhortion [1978]. If these photos are not about the whole idea of fugitivity, I don’t know what else they’re about. She takes a picture of a person next to, I guess she’s next to a traffic light, and where she’s not in silhouette, her hair is blocking her face. These are masks, people who are masked. There’s a certain masquerade dimension to these photos.

And in Prelude to Middle Passage [1972]. This is a photo in which the figure is defining the background. It’s framing the background! [Laughs] The background is not framing the figure. The figure is framing the background. In Invisible Man, that’s the blur. The traces. The phantom. The fugitivity of people willing to be free from being fucked with. You can’t fuck what you can’t see. Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee; you can’t fuck with what you can’t see!

This conversation was originally published in Ming Smith: An Aperture Monograph (Aperture/Documentary Arts, 2020) under the title “The Sound She Saw.”