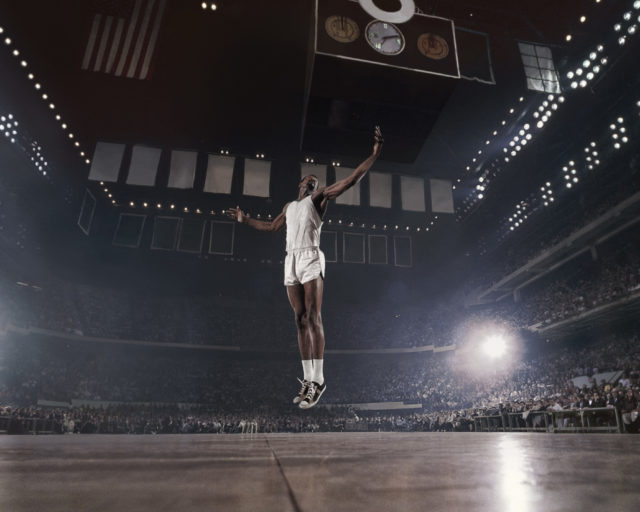

Gregory Halpern, Untitled, 2019, from Let the Sun Beheaded Be (Aperture and Fondation d’entreprise Hermès, 2020)

Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa: This new work you’ve made is a little unusual relative to your earlier work, in that you’re making photographs in a place that’s distant from you and relatively unknown to you. Up to now, you’ve only made work in the US, and yet here, you’re making work on the Caribbean island of Guadeloupe. How does your relative distance from it all inform the way you’ve approached the project?

Gregory Halpern: It’s true—a lot of my work is about the American experiment, its promises, its failures, and trying to look at that in new ways. But in Guadeloupe, I felt overwhelmed at times by the sense that I was such an interloper. The constant awareness of being a white, American man with a camera in the Caribbean, the relationship between photography and colonialism, the fear that I was no more than a glorified tourist—all of that was creatively paralyzing at times.

For the Immersion commission, I was asked to propose a project based in France. I spent a lot of time thinking about how and where I could work in “mainland” France. I struggled with that question until I realized that it might be interesting to think about France through the experience of a former French colony and landed on Guadeloupe, a modern-day “overseas region” of France.

The barriers were much larger than in previous projects, and my French is pretty poor. Plus, the weight of history there felt immense; it felt unknowable to me in a way that I wasn’t used to. So I felt much less confident at first editorializing in Guadeloupe than I did in, say, Los Angeles—which by comparison I knew quite well, and where I felt more comfortable imposing my vision on the place.

Wolukau-Wanambwa: What was notable to me in looking at the first and then especially the second edit of the book, was the extent to which you’ve found a means to address concerns that I’d argue are integral to your ongoing project as an artist, but from Guadeloupe. I see you looking at death and violence as they’re figured in the earth, in symbols, and on bodies; I see you working across an epic register of forms of light: that seems to me very consonant with your ongoing work.

Halpern: I’ve never been one to make quick photographic visits, especially to foreign countries, so making this work in less than three months was a challenge. I like to sit with the work, show people, figure out what’s working and what’s not, and then return to making pictures with a more informed vision. Both ZZYZX [2016] and A [2011] took five years to finish, and Omaha Sketchbook [2009/2019] was made over fifteen years. But I think you’re right that almost whatever I photograph, I tend to think about the same sets of issues, and want similar ideas and feelings to drive the pictures.

Wolukau-Wanambwa: Do you worry at all that there might have been a different story to be told, but that you were incapable of telling it, whether in this accelerated time frame, or perhaps at all?

Halpern: I worried about both. The time constraint forced me to be productive, but the fear was that I would be desperate to come back with images, without having the time to consider if they were the right images. And yes, a story I couldn’t tell was a story from the perspective of an insider. I worried whether that story would be more compelling than mine could ever be.

Wolukau-Wanambwa: For me, from your vantage point as an outsider, the photograph that most powerfully forces us to reckon with the continuities and discontinuities pursuant to slavery, colonialism, and their aftermath is the one of a dark black male figure with the fisherman’s hat, who stands in the water, carefully carrying the recumbent figure of a white woman. It’s incredibly beautiful, and it’s suffused with the explosively uneven nature of racialized difference, which is as central to the United States as it is to colonial France. I imagine, or I hypothesize, that your way “in” to making work in Guadeloupe might have been to look at it as someone who is an inheritor of settler-colonial violence, and to make work from that standpoint.

Halpern: You’re right that the histories of the two places are not entirely dissimilar, but the trauma of slavery and colonialism somehow feels so much more raw there than in the US. Perhaps the contemporary, semicolonial relationship with France continues to irritate those wounds? But also, the vast majority of the population of Guadeloupe is black, which helps ensure that that history is not relegated to the margins. There’s an incredible number of slavery-related memorials, for example, and there’s nothing like that in the US. They address very directly the violence and trauma of the past, and picturing them was simply one way of trying to visualize that history.

As for the photograph you mention, I liked how that moment was hard to read. Who is playing what role? Are the arms of the dark figure protective or menacing, loving or servile, a reference to the “utility” of colonialism’s past—or present, for that matter, because it’s the labor of locals that carries tourists, as if they were weightless, through their island vacations.

For a picture to work there has to be something that defies expectation, that surprises or unsettles or nags at you, something that doesn’t just reaffirm what you already know or feel. For me, that picture did that.

Wolukau-Wanambwa: Did you try to photograph regular forms of labor and activity? Were you thinking about work specifically? Did you make a choice to more or less avoid the tourist trade?

Halpern: I tried photographing the tourist trade at points, but the pictures were caricatures or one-liners. I couldn’t seem to get past the sort of ridiculous look or “character” of the tourist. There’s a clichéd or clownish image of tourists we all know—bad style, pasty skin, camera, English spoken with an air of loud entitlement—it’s an image we know, true or not, and my pictures sometimes couldn’t get beyond that reference. Or if they did, they functioned within the book to suggest two polarized worlds—tourists and locals— which is a legitimate way of viewing the island, but it made for a more reductionist reading of the book. The individuals pictured became symbols of one group or another, and it felt somehow an injustice to everyone.

In relation to labor, I have recently gone back to Guadeloupe to make a video, which touches on it. There’s a market in downtown Pointe-à-Pitre near the harbor, and when the cruise ships dock, hundreds of tourists flood downtown for a few hours. They stroll into the market and inevitably photograph the women working there, usually without asking permission. The women sometimes respond by yelling “no photo” at the tourists, annoyed that they haven’t asked permission, or bought fruit, or even said hello first.

I sat there one day and watched the dynamic, mesmerized. It was unsettling. I was shocked by some of the tourists’ brazenness and disrespect, shooting as if on a safari, not talking or making eye contact. I found myself sympathizing squarely with the workers as they yelled at the tourists, and yet I also couldn’t help but recognize myself, at least to a degree, in the tourists. There was something quite powerful and instructive in that dynamic being laid so bare.

Wolukau-Wanambwa: I can certainly see how heavily the images you excluded would skew the balance of symbolism in the book toward fundamentally external concerns. They sound a loud, interrupting note. Are there other images in the book that emerge from you trying to look outward from a Guadeloupean perspective, or from following an island dweller’s instructions or invitations as to where to go, or where to look?

Halpern: Maybe half of the images are the result of advice from a Guadeloupean. I tend to wander and talk to a lot of people. I’m sort of a sponge when I have the camera, accepting just about any invitation, picking up hitchhikers, following stray cats down alleys, et cetera. I often start the day with a vague plan, maybe choosing a spot on a map or returning to a place where the light was poor previously. I rarely stick to the plan, but the plan is an important starting point, because it gets me out the door.

Wolukau-Wanambwa: Can you describe a few of the conversations you had with people in Guadeloupe as you made the work, and perhaps speak to the extent that they’ve varied from or mirrored conversations you had in Los Angeles or Omaha, Nebraska, or Buffalo, New York?

Halpern: I think my conversations are pretty similar no matter where I am, but it was definitely more of a challenge to connect with people, because my French is mediocre and very few people are fluent in English there. There were a lot of photographs I couldn’t wind up making well because of language, and perhaps because of my timidity as an outsider, but nonetheless, I occasionally still made strong connections, and that’s always amazing when that happens. Twice in my life, I’ve made portraits of people where the only communication was with hand gestures and facial expressions—once there was a lot of smiling and laughing at ourselves, and once it was just really silent and peaceful, but both times were intense and beautiful experiences.

It’s always hard photographing people, though, even when you speak the same language. I’m pretty introverted, and I usually still have to work up the nerve. I tend to approach people in a sort of formal way—respectful, positive, honest, and direct about what I’m doing. I’m always aware of what a huge ask I’m making. I’m aware of the skepticism I’d feel if a stranger approached me on the street asking for a portrait, and that’s always in the back of my mind. And I carry a little laser-printed card that I hand to people, so they know how to reach me if they want copies of pictures. A lot of people don’t follow up, but I think the gesture is appreciated nonetheless.

Wolukau-Wanambwa: Can you speak about the ways in which your Jewishness informs your sensitivity to ethnic and racial difference? I’m thinking about the ways that certain racial and ethnic differences can go unobserved, and the ways your own personal experiences might attune you to the different, but related, inequities that others suffer.

Halpern: I’ve generally been uninterested in making work about myself or my identity, but increasingly, I’ve come to think my Jewishness is a powerful reality in the background that has deeply shaped how I see. My brother and I were the only Jews in our high school in Buffalo, and there was the sense that it was wise to just “pass.” Oddly that sentiment has lingered, and I sometimes still find myself wondering whether or not to “out” myself in conversations. My grandfather fled Hungary just before the outbreak of the Second World War and snuck into the US illegally because of anti-Semitic immigration laws. I am alive because he made that journey. The family who stayed in Hungary was almost entirely killed in extermination camps by the Nazis, although my great-aunts Olga and Goldie somewhat miraculously survived Auschwitz.

When I was a kid, usually at Thanksgiving, my dad would almost ritually ask my grandfather to tell the story of coming to the US—two weeks hidden in the bottom of a boat, going to the bathroom in the corner. And so this became our family’s origin story—fleeing genocide and sneaking into a country that did not want us. I have a complicated relationship to this story, and over the years have felt various combinations of pain, shame, strength, and pride in relation to it. And then there is the history of those who did not escape—the photographs of the piles of pale, malnourished bodies I somehow saw as a child, and which became, and perhaps remain, the primary association I have with the word Jewish. It’s such an overwhelming experience to see those pictures for the first time, especially as a child, that that becomes your people and your history.

Of course, whether or not Jews came to this country legally, they came of their own volition, not as enslaved people. Whether or not it’s useful to compare griefs, I don’t know, but there is something quite dark and not often talked about in the inherited trauma of Jews. I think it manifests itself in strange ways. It may be present, if latent, in the pictures, which is not to say that viewers need to know any of that when looking at the pictures, but I do think perhaps it’s there. Narratives and traumas across cultures are obviously different, and I don’t make this point to overlook or discredit the singular experience of any one narrative, but I do feel that through art there is the potential for shared experience, for some form of transcendence.

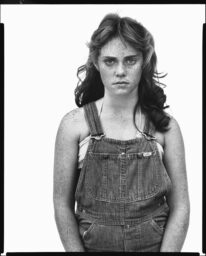

Photographer unknown

The family photo above was taken before the Nazis invaded in 1944. My grandfather had already left Europe, so he is not pictured. Of the rest, all but three were killed in Auschwitz. Of those three, my great-aunt Olga (the young girl in the gray dress, second from left) is the only one still alive, at age ninety-two.

All this makes me think of a 2019 New York Review of Books piece by Zadie Smith called “Fascinated to Presume: In Defense of Fiction.” It’s a remarkable piece, running counter to the current mood, that argues for the potential value of portraying the “other” as a possible form of connection:

[W]hat insults my soul is the idea—popular in the culture just now, and presented in widely variant degrees of complexity—that we can and should write only about people who are fundamentally “like” us: racially, sexually, genetically, nationally, politically, personally.

She goes on to argue that in our own deeply personal, unique experiences of grief, there is the potential for us to know each other:

I was fascinated to presume that some of the feelings of these imaginary people—feelings of loss of homeland, the anxiety of assimilation, battles with faith and its opposite—had some passing relation to feelings I have had or could imagine. That our griefs were not entirely unrelated. . . .

What do I have in common with Olive Kitteridge, a salty old white woman who has spent her entire life in Maine? And yet, as it turns out, her griefs are like my own. Not all of them. It’s not a perfect mapping of self onto book—I’ve never met a book that did that, least of all my own. But some of Olive’s grief weighed like mine.

Wolukau-Wanambwa: I think that you’ve often made photographs that engage with the production of difference, or the individuated experience of racial difference particularly. I’d argue that your sensitivity to, and your compulsive interest in the forces that shape how we might articulate our inchoate selves, and the forces that might limit our capacity to be receptive to others, are central to much of the work you’ve made. One thread that runs through some portraits is a powerfully reflexive figuration of difference. You make photographs that point to the activity of picturing in complex and expressly racial ways. Do you think that your sensitivity to the reduction of Jewishness to images of emaciated corpses, or the reduction of Jewishness to anti-Semitic tropes that are expressly visual, might inform your relationship to imaging more broadly? I think about this as a black photographer too: I know how the power of looking can shift suddenly, radically, and all too often dangerously, and that has a meaningful effect on the ways I think about seeing and about images.

Halpern: That’s a great question. I don’t know the answer. But I think there’s something fascinating there—especially when I think about the ability of images to work powerfully on our unconscious mind, and how susceptible we are to being manipulated visually, be it through propaganda or advertising.

At the same time, I’m pretty skeptical of the power of images to transform reality or to create change. More and more, I’ve come to feel that change happens almost exclusively through protest and direct political action, when enough people come together to create a tipping point. I think that the art world is driven too much by capitalism to have any teeth as a political tool. I’m not sure any highly collectible commodity can ever really bite its owner, so to speak.

On the other hand, making art is a way of participating in a conversation, and conversation is perhaps the starting point for all change. The images of the [extermination] camps, for example, transformed reality for me. As did a book by Milton Rogovin, which I also saw when I was a boy. Rogovin lived and photographed not far from where I grew up in Buffalo. He made portraits of the same people over the course of twenty-five years, and when I first saw his work, as a teenager, I was shaken to the core.

I remember feeling confused, almost ashamed, that these pictures of strangers had moved me to tears. I hadn’t known art could do that. That book changed the course of my life, and so in that sense, I can’t deny the power of images to create change.

The impact of images is so hard to quantify. It’s so internal, like they skip past the cerebrum and get deep inside, into the body. It’s like they have the power to bypass the conscious mind and infiltrate without us knowing how, or what they’re doing once they’re inside. We think we know what we’re seeing, at least we tell ourselves that. But it’s more like we never really know what we’re seeing.

What about you? Are you ever discouraged to think that what we make are “just pictures”?

Wolukau-Wanambwa: I recognize precisely the quandary you’re describing, if that’s the right word. How can making objects that circulate in relatively or absolutely small numbers for middle-class people, or infinitesimally in even smaller numbers for wealthy collectors and institutions, be considered a form of radical political action? I get that, and I’d agree that it’s not. I think that there’s a very good case to be made that says that these activities are not inherently radical forms of political action, and that they cannot be divorced from normative politics either.

I think we’ve also certainly seen meaningful social and political mobilizations in physical space as a response to both art images (Dana Schutz) and to the terrible realities approximated by nonart images (Michael Brown, Eric Garner). The circulation of those images does have real-world consequences, even though we need to be careful in those cases not to mistake the image for the real.

Do you think that a viewer of your work would respond differently if they viewed your photographs as fiction rather than as indexical fact? Would adopting the stance of storyteller—à la Zadie Smith—rather than documentarian, alleviate any of the contemporary concerns we’ve been discussing around difference and the structural violences meted out against the marginalized? I have this sense from so many discussions in the contemporary American classroom, that the identity position of the author matters far more than genre today.

Halpern: I agree with you about the emphasis on the author’s identity position, especially in the American classroom. After centuries of (mis)representation, there’s a need for marginalized groups to take ownership of their own narratives. And increasingly that’s being celebrated, and that’s essential. But in my eyes, it doesn’t eliminate the need to connect, to try to create something transcendent, or to look for the shared weight of experience across those lines that separate us.

Lately, I’ve been thinking about Marina Abramovic ́’s The Artist Is Present—when over the course of nearly three months in 2010, for eight hours a day, Abramovic ́ sat in a chair at New York’s Museum of Modern Art and stared into the eyes of one person at a time, often for longer than five minutes each—and thinking about how so many of those sessions ended in tears. As children we’re taught not to stare, especially at strangers, and among adults, staring is often considered offensive or threatening. I’ve always been fascinated by how, through portraiture, the face of a stranger can take on meaning for another stranger, how an anonymous viewer can look at that person—a person who should mean nothing to them—and feel something. In an evolutionary sense, there’s no logical reason why one stranger should feel something for another. To me, there is something deeply mysterious and hopeful knowing that we can react to each other that way.

But to get to your question, I see fiction and nonfiction as existing on a spectrum. If science fiction represents one end of the spectrum and journalism represents the other, the middle might be occupied by things like lyric documentary, creative nonfiction, and perhaps, photography itself. I definitely borrow from a documentary tradition and aesthetic, but I have difficulty with the term documentary. It carries so much baggage, and is too often misunderstood as implying indexical fact. Once you claim the authority to understand and represent another’s reality, you’re sort of on shakey ground, as far as I see it. In that sense, to call the work fiction seems more honest.

But it can be both liberating and unsettling to not know how to classify work. When you pick up a book of literature, it’s usually categorized right on the back cover (fiction or nonfiction), and that can be helpful in knowing how to read and process the work. That doesn’t exist in photography, which is interesting.

What about your work—One Wall a Web [2018], for example —how would you classify it in terms of traditional genres?

Courtesy the artist

Wolukau-Wanambwa: I think that to some extent (but by no means universally) in this identitarian moment, and especially in the (white) liberal art world, who you’re perceived to be as an artist can often dictate what your pictures can say, which then handily relieves a viewer of working that out for themselves. For me, the term documentary is one that I would want to reclaim in all its inherent complexity, rather than abandon it. I think that what I sought to document in One Wall a Web—far beyond a specific place or person—was the enervated psychic states from which white-supremacist, white-heteronormative violence flows. I wanted to document that violence as a real but also importantly intangible force. I tried, through the structure of the book, to trace its presence and effects on the landscape, in and on and around differing people, and through a history of appropriated photographic images and texts that extended into those images and texts I made in the present tense. In that sense, a lot of my “subject matter” is ethereal, immaterial, and inherently fantasist. So the forms of realism I needed varied over time, and those variances (hopefully) help to break up any notion that there’s one stable, transparent, objective lens through which what’s on offer can be reliably seen and understood.

To come back to your earlier points about the perils and virtues of categories like documentary, I think that maybe we’re focused on a symptom rather than the cause. I think that many of us in the Western world are exhausted, overstimulated and undercooked, overworked and undereducated, full of sensations and terrified of feeling, full of thoughts and uncertain how to think. I think that veridical statements and notionally credible documents (“real” news vs. “fake” news; “documentary” images vs. “fake” images) help to alleviate some of our interpretive anxiety. Simplifying our sense of the world by outsourcing interpretive responsibility for understanding it is appealing, precisely because we’re drowning in false choices all day long. I think that we sometimes need to believe that facts are simple, and that documents are true.

Halpern: I think you’re right, and in a way, that’s what concerns me about photography—that at times we all want to be fed facts, that we want to trust what we see. It’s unsettling to think of photography as fiction, but I think it can be useful.

Earlier, when you critiqued the notion of art being “reliably seen and understood,” I was struck by the idea of reliability and found myself thinking about the unreliable narrator in literature. I love the idea that a reader can’t trust an author/artist even when they appear to be telling the reader what to think. It forces the reader/viewer into the uncomfortable, but important, position of having to decide for themselves.

I am thinking here of the way William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury [1929] might get at the messy truth of a single family more than any traditional documentary about a family might. As a narrative strategy/structure, it’s just such a beautiful way of speaking to the impossibility of “telling the story” of a single family, in all its inconsistencies and contradicting truths. In that sense, I find the deliberately fractured nature of One Wall a Web, with its multiple “narrators” or “voices,” similarly beautiful and a fitting way of documenting, as you say, the “enervated psychic states from which white-supremacist, white-heteronormative violence flows.” That is an impossible thing to “document,” as I see it, but the dilemma of that impossibility is one of the things I find compelling about the work, and I like that you don’t shy away from the word. Maybe for documentary to be reclaimed, it needs to be embraced in that way, by artists who are working in profoundly innovative and experimental ways, who celebrate not only its potentials but its pitfalls as well.

This interview and images were originally published in Let the Sun Beheaded Be (Aperture and Fondation d’entreprise Hermès, 2020).