Gus the Bear

This essay was first published in issue 206 of Aperture magazine (Spring 2012).

Stop and go: always on some journey. My bounty is a photograph or two. I remember what pulled me, an instant of clarity, a moment of perfection, but where was I? Beyond the edge it often fades to darkness: I don’t always remember the season or the place.

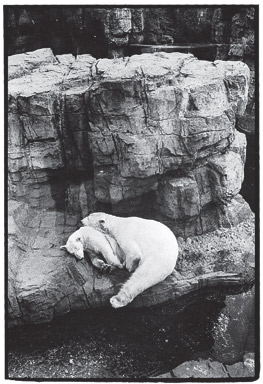

But with Gus and Ida, I do remember. It was 1988. They were new residents of the renovated Central Park Zoo, which finally saw the end of those cramped little nineteenth-century cages. Gus was brought from Toledo and Ida from Buffalo. They were both rambunctious and about three years old—preteens, in polar bear terms. I saw them through the glass wall of the pool gliding and frolicking in their white buoyant bulks. What joy! I saw them again in 1992 resting on a rock, quietly locked in an embrace.

Almost twenty years passed and then last summer, I read in the paper that Ida had died and Gus was now alone. The morning I went to see him, he was nowhere to be found. I asked a woman standing next to me if she knew where Gus was? “I think he is in mourning,” she said, as though mourning were a place—some dark cave— rather than a state of being.

When I came back that afternoon, I knew from the commotion and the way the children were squealing that Gus was present. And there he was, a glorious thousand pounds, with eyes half-shut swimming back and forth, as if pacing. Each time he reached the outer edge of the pool, and before he threw himself back again into the water, he pushed himself up, raised his bushy head, shook off the water and took deep whiffs of the air—looking for Ida, I thought. Poor Gus.

I tried to find someone who might have known Gus over the years. The zoo officials didn’t know, didn’t care, said they’d call me. The zookeepers were busy and too young. All channels were blocked. I turned to the chatter on the Internet. Through the noise and PR jargon and giddy superficiality, I gleaned that Gus had been depressed before; some called him “the bipolar polar bear.” He had had expensive psychiatric therapy, and occasional relief with toys and distractions. Ida joined him in 1987 and Lily, another female bear from Germany, came a few years later and shared the “enclosure.” Lily is gone, too; she died seven years ago.

Time stands still in photographs. Like the guys in John Keats’s “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” the bears remain forever suspended in motion. Gus and Ida’s idyllic underwater dance, my illusion that all was well in some small corner of the world, was the truth only of that one second, a break in hours of tedium. Though there must have been many good moments and many visitors have been cheered, a zoo is a zoo: an enclosure is a prison. Outside, on the other hand, fear and hunger are frequent companions: Nature is not all it’s cracked up to be. Life anywhere is good only in spurts.

Now in this new portrait of Gus, he is alone. He is too old, I hear, to get used to yet another bear, his toys are really just plastic buckets, and as he continues his joyless swim at the dark side of the pendulum, he yearns for something—he doesn’t know what— perhaps not just his lost Ida.

As I leave the zoo, I read a sign on the fence: “Treat each bear as the last bear.” There is no source, no explanation. I am left with another riddle.

All photographs © Sylvia Plachy, 2012