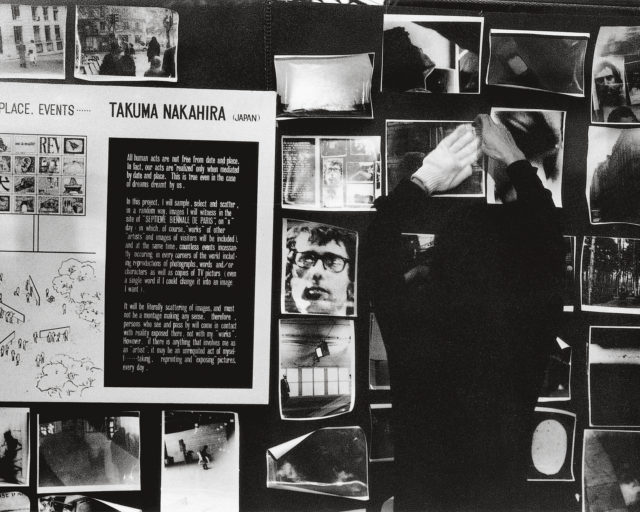

Higher Ground

Vittorio Sella, born in the foothills of the Italian Alps, combined his passions of photography and mountaineering to capture the elevated beauty of the world’s most inhospitable places. An excerpt from “Odyssey,” the Spring 2016 issue of Aperture magazine.

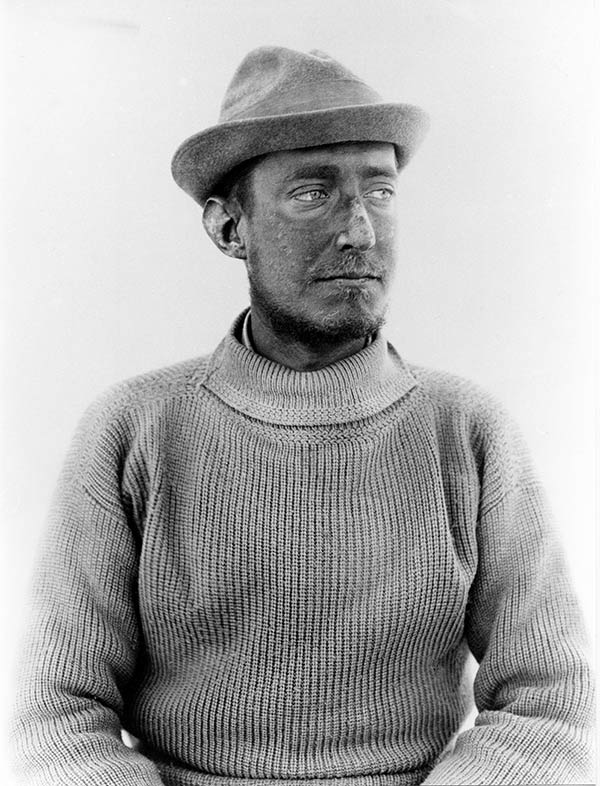

Vittorio Sella, Luigi Amadeo di Savoia-Aosta at age 24, just after returning from Mt. St. Elias, 1897

Mountains are powerful symbols of eternity, of the immensity and grandeur of nature, towering above and indifferent to human civilization and history. Yet our interest in and preoccupation with mountains—climbing, studying, painting, and photographing them—are the products of a very recent history.

High and remote mountains, which earlier European generations avoided, viewing them as dangerous wastelands inhabited by the poorest and most backward people, suddenly took on new appeal in a rapidly industrializing nineteenth-century Europe. Romantic poets longed to escape from the “dark Satanic mills” (William Blake)—the factories beginning to dot the landscape—and from the “getting and spending” (William Wordsworth) of growing urban life. Wordsworth, Coleridge, Byron, and Shelley all wrote about the powerful, formative experiences of their visits to Mont Blanc and their encounters with the mighty Alps. “High mountains are a feeling, but the hum / Of human cities torture,” Byron wrote. While the eighteenth-century traveler concentrated on the ancient sites of Italy and Greece, the Alps became an obligatory Grand Tour destination for cultivated young English gentlemen of the nineteenth century. John Ruskin, Victorian England’s most influential tastemaker, proclaimed, in 1856, that “mountains are the beginning and the end of all natural scenery.”

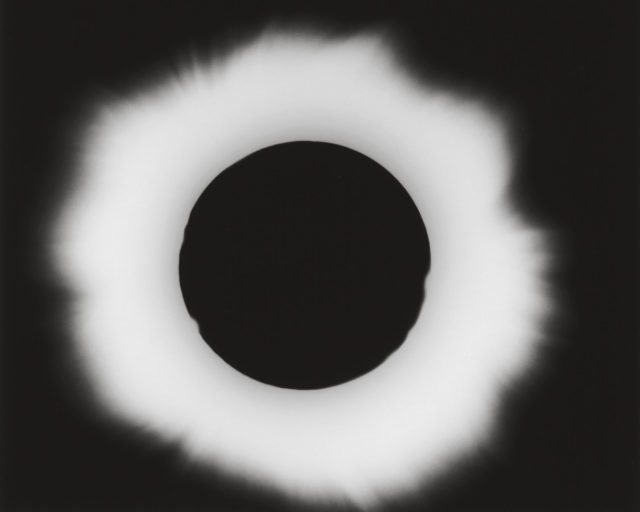

Vittorio Sella, Crevasses, Glacier du Chardon, August 3, 1888

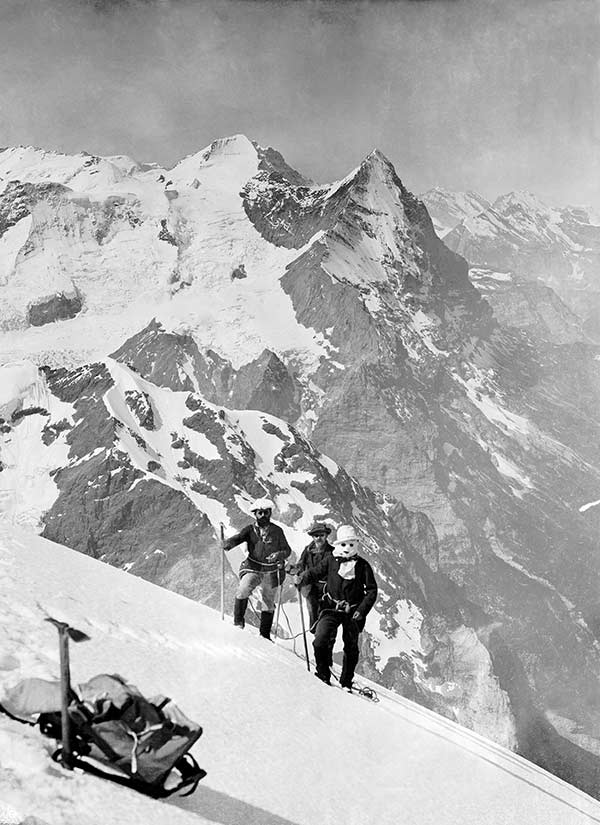

This sudden awareness of the mountains, together with improved transportation and technical capacity for systematic mountain climbing, tempted Europeans not just to admire the mountains from below but to see the world from their heights. In the mid-nineteenth century there was an active scramble—a kind of friendly, international competition among a new class of gentleman mountaineers and explorers—to reach the remaining unexplored peaks of the Alps, the last frontier of nature in Europe untouched by man. The ascent in 1854 of the Wetterhorn—one of the highest peaks in Switzerland—by British climber Alfred Wills was an international event, ushering in the “golden age” of mountaineering and the formation of the Alpine Club in 1857.

Vittorio Sella, mountain-photography pioneer, was born in 1859 into a family of explorers and photographers in the town of Biella, in the foothills of the Italian Alps, where his family ran a successful wool factory. A few years before Sella’s birth, his father published the first major treatise in Italian on the new science of photography. When Sella was four years old, his uncle, Quintino Sella, led the first expedition to the top of Monte Viso (or Monviso), the highest mountain in the French-Italian Alps, and in 1863 founded the Club Alpino Italiano, which remains Italy’s principal mountaineering club.

Vittorio Sella, The Duke of Abruzzi and guides climbing through Chogolisa Icefall, 1909

Sella’s father died when Sella was just sixteen, leaving him in the care of his uncle, an important and emblematic figure in nineteenth-century Italy. After getting an undergraduate degree in engineering, Quintino Sella studied mineralogy at the École des Mines in Paris, then returned to Italy, where he taught mathematics and mineralogy. During his frequent ascents, he gathered samples of unusual rocks, assembling one of Italy’s most important collections of minerals. He was placed in charge of a new royal museum of mineralogy in Turin, which was the capital of the Duchy of Savoy, home to what would become the Italian monarchy. Quintino Sella entered politics in 1860 and became Italy’s minister of finance in 1862, after Italy was unified. The conquest of the alpine peaks was not entirely divorced from the politics of the newly unified Italian nation: Quintino Sella shrewdly included a member of parliament from Calabria in his ascent of Monte Viso, making the climb a public moment of patriotic unity.

Vittorio Sella, Alessandro Sella, Joseph Maquignaz, and Gaudenzio Sella on the Wetterhorn, July 19, 1886

Vittorio Sella synthesized his father’s expertise in photography with his uncle’s passion for mountaineering. When he was nineteen he made his first serious effort at alpine photography, dragging heavy, borrowed photography equipment up to Monte Mars and making his first panoramic views of the Alps. At the time, he was working with extremely cumbersome and volatile wet-collodion glass-plate negatives. With this method a photographer needed to coat each plate with a silver-nitrate solution and develop each shot within ten or fifteen minutes of exposure, while the negative was still wet. This meant that Sella had to carry and improvise a portable darkroom up in the Alps. Despite the technical difficulties and uneven photographic results of these initial efforts, Sella persisted, learning a great deal through the trial and error of an art that was still in rapid evolution. “From 1880,” he wrote, “I made up my mind to combine photography with Alpinism, and I took almost no interest at all in the lower parts of the mountains, and confined myself to photographic work on the summits, and to those higher regions of the Alps, which were little known and had not been photographed.”

Fortunately for Sella, photographic technology was evolving; particularly revolutionary was the development of the gelatin process—glass plates with a dry photographic emulsion—which meant that negatives could be prepared in advance and developed later. The new dry negatives were both more convenient and exceptionally sensitive, allowing for shorter exposure times and remarkable photographic detail.

Vittorio Sella, The Karagom Glacier as seen from its right moraine, Caucasus, 1890 © Fondazione Sella and courtesy Decaneas Archive

Sella was a pioneer in mountaineering as well as photography. In 1882, he led the first group to successfully climb the Matterhorn (known as Cervino in Italian), the largest mountain on the Italian–Swiss border, during the winter—an achievement hailed by the Alpine Club as “beyond doubt the most remarkable that has ever been made during the winter season.” Later that same year, in a fever of excitement, he wrote to the camera company J. H. Dallmeyer in London: “I beg you to undertake immediately the camera for plates 30 × 40 cm described in my letter. I beg you to make it in the best mahogany, with every care possible, as I will serve myself of it for taking photographs in the high Alps…Here, we have splendid weather and I burn with impatience to start photographic excursions.”

The camera that Sella acquired from J. H. Dallmeyer weighed nearly forty pounds; each glass plate, almost two. Despite this exceptional challenge, Sella managed to get the camera and plates back up the Matterhorn, where he began to make some of the pictures that established him as the premier mountain photographer of his time.

To see this article in its entirety and read more from “Odyssey,” buy Issue 222, Spring 2016, or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.