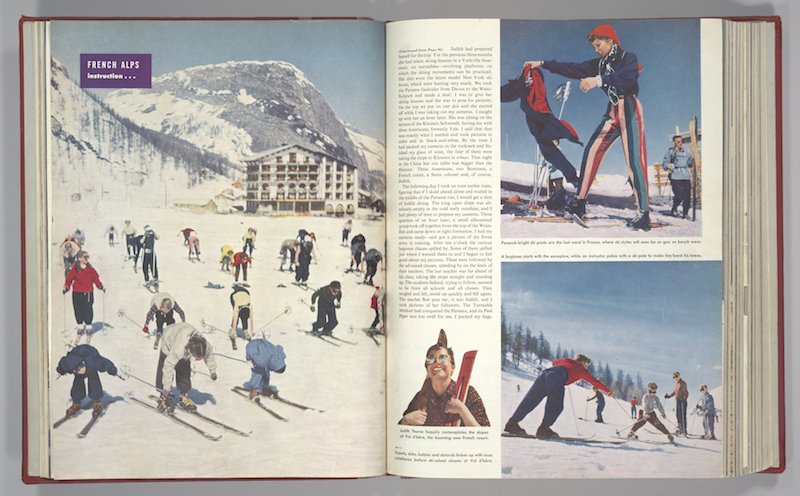

On Holiday

As spring begins we revisit the pages of vintage magazine Holiday, a luxury title launched in the 1950s and became widely known for its ambitious and opulent photographic spreads. In this excerpt from Aperture magazine issue #198, Mary Panzer, a historian of photography and American culture as well as curator, tours us through the history of the former magazine, which featured photo stories spanning everywhere from Japan to Havana, by photographers among the likes of Robert Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and Elliot Erwitt. This excerpt first appeared in Issue 5 of the Aperture Photography App: click here to read more and download the app.

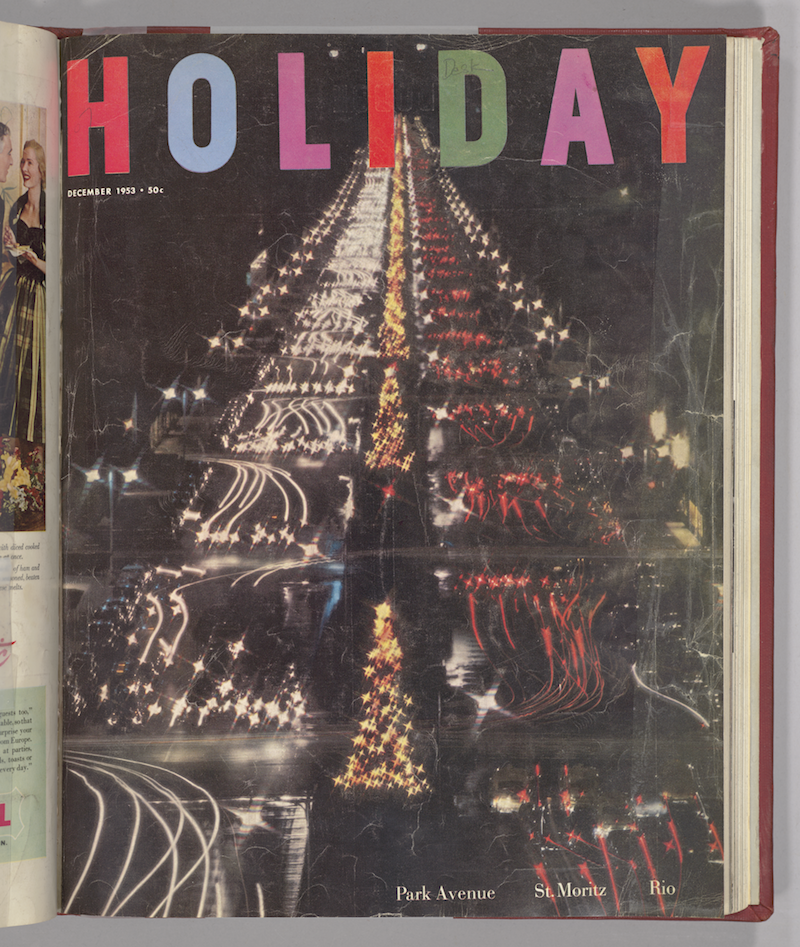

Cover photograph by Slim Aarons

Holiday magazine was launched in 1946 and appeared monthly until 1977. It was the first postwar project of Curtis Publications, publisher of the Saturday Evening Post and Ladies’ Home Journal, and corporate rival of Time/Life. Holiday preserves a clear document of the growth of the American photojournalism in an era of flux. When the magazine started, there was no Cold War, no rock ‘n’ roll, no civil rights movement, and fewer than 10 percent of families in the United Sates owned a television; in just the next fifteen years, that world would be turned upside-down.

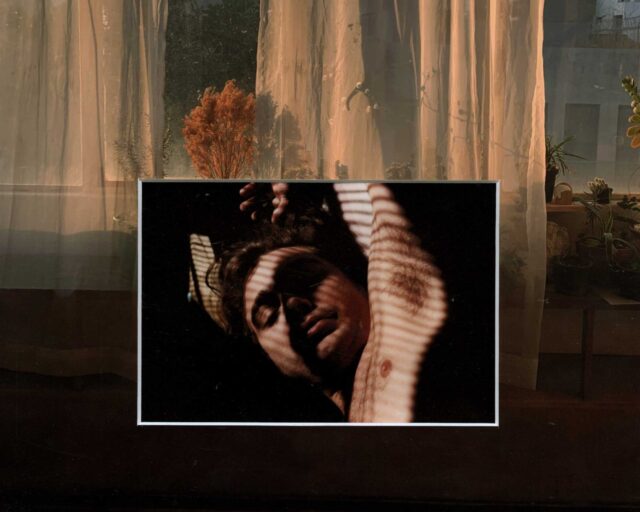

Photograph by Slim Aarons

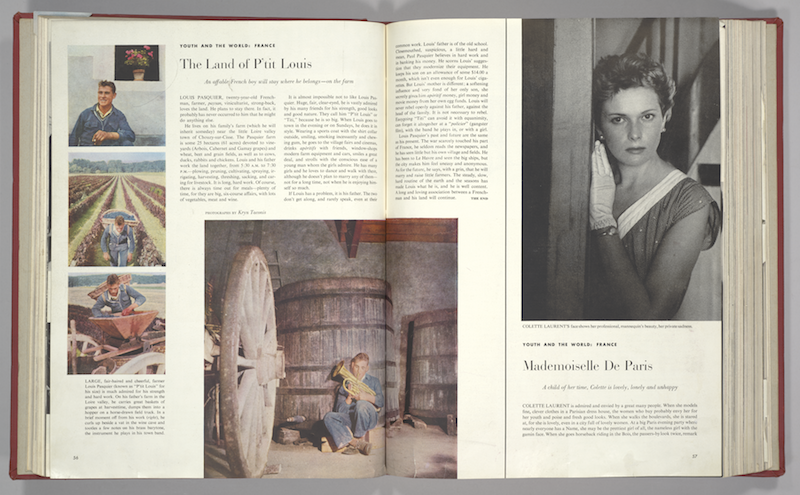

During its best years– roughly 1951-64– Holiday regularly reported on American culture, European recovery, traditional travel spots, exotic places, playgrounds of the rich, and popular culture, including food, movies, and television. Part-Fortune, part–National Geographic, part-New Yorker and Gourmet, Holiday reflected the vision of founding editor Ted Patrick, a self-made man, a risk-taker, and an intellectual who enjoyed the good things in life. Patrick spent his early career in advertising, and served as the director of publications at the Office of War Information (OWI) during World War II before being hired by Curtis. In 1951 Patrick brought in Frank Zachary (also a OWI veteran) to be art director of Holiday. Zachary was a talented writer and graphic designer who, in the 1940s, turned the “how” magazine Minicam into Modern Photography, a lively journal for professionals and serious amateurs. Zachary was also a follower of Alexey Brodovich.

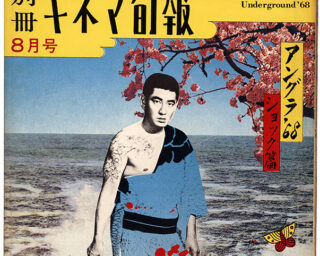

Photographs by Robert Capa

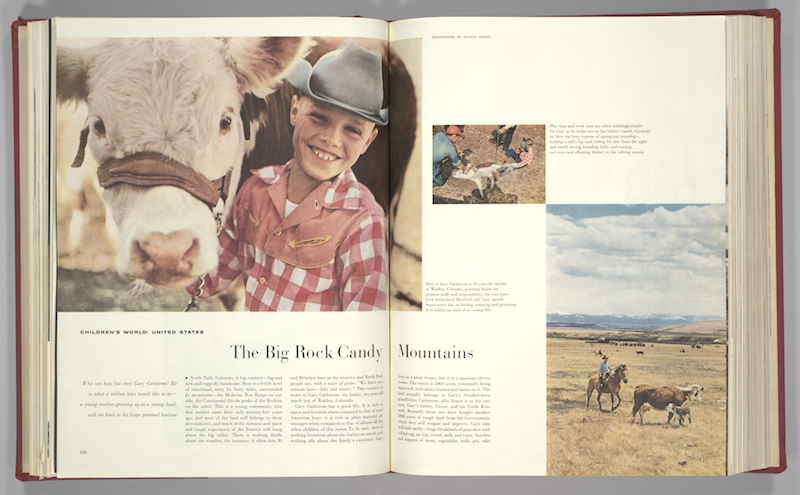

Through Holiday. Patrick promoted his belief that those lucky Americans who had survived the war had a responsibility to make something of their prosperity, productivity, and leisure. As he wrote in the pages of Holiday’s tenth-anniversary issue (March 1956): “We now have the means, money and products by which to achieve the fullest, richest life ever known to mankind, and we now have the unprecedented time of our own, which might be the greatest gift of all. What we do with that gift will decide the quality and the place in history of American Civilization.” Patrick’s confidence in the power and potential of his fellow Americans now seems like a scrap of early science fiction: a bit prescient, a bit quaint, and largely wrong.

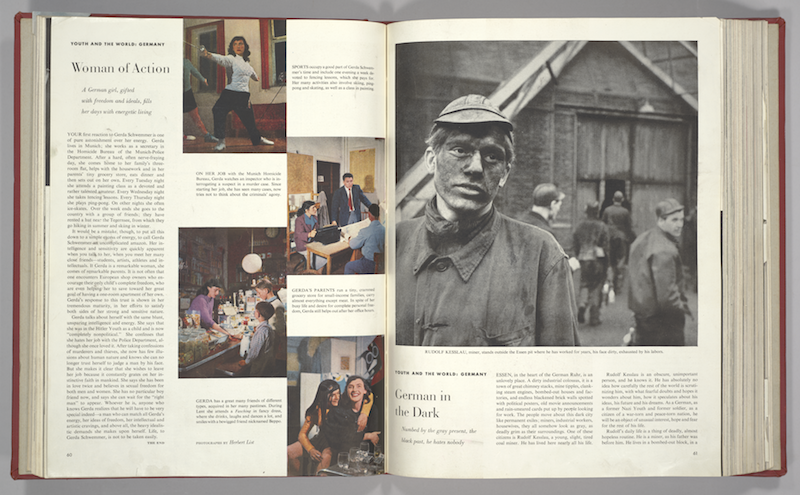

Left: photographs by Herbert List; right: photograph by Robert Capa

Despite the magazine’s title, Holiday was not simply a guide to new vacation spots. The articles were meant to educate and enlighten. A story on Wales, for example, included gorgeous scenery, a trip through a coal mine, and a visit to a small village where music formed an important part of everyday life. Patrick seemed unconcerned by the paradox of teaching readers to seek out places and people who were not for sale, while his magazine was supported by ads for luxury commodities like cars, liquor, cigarettes, cruises, and cameras . . .

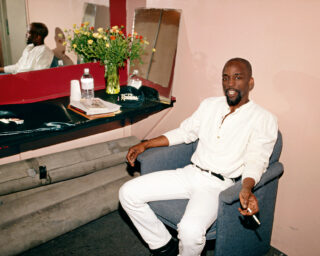

Photographs by Elliott Erwitt

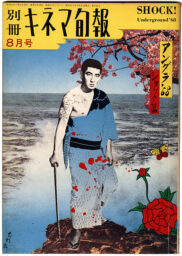

From the start, photography comprised an essential element of the magazine. Patrick gave photographers generous budgets and deadlines, and very little direction. Photographers Tom and Jean Hollyman, who often worked as a pair, received these typical instructions from the managing editor: “Go to the French Riviera, Portugal, Lichtenstein, and one or two other places (we haven’t made up our minds which). Go in whatever order appeals to you. And let us know what you need in the way of research or dough.” They stayed away for a year. Burt Glinn reported the same casual generosity for his trips to Japan, the Soviet Union, and the South Seas, though his trips were shorter– only four to six months. . . .

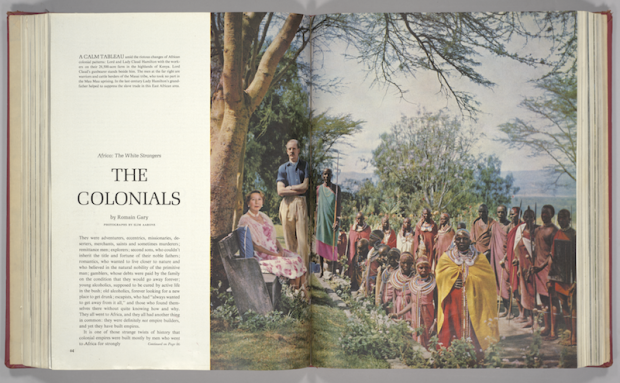

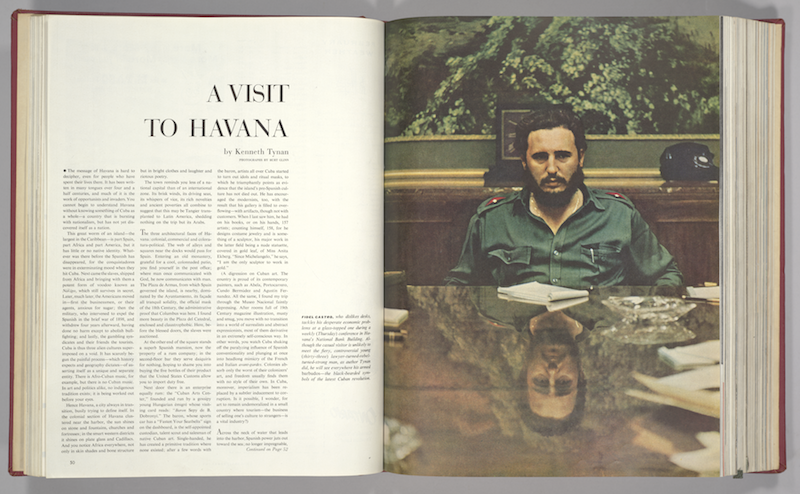

In the early years of Holiday, color images were largely conceived and utilized in the same ways that black-and-white pictures of the 1930s had been. After Zachary arrived, the quality of photography and layout grew more sophisticated: bigger pictures, more white space, more telling details, and fewer generic vistas. Outside the magazine’s staff– which included such names as John Lewis Strange, George Leavens, Ray Atkeson, Ernest Kleinberg, Bob Smallman, Ike Vern, and Rosa Harvan– Zachary gave assignments to photographers who had special experience or access: Dan Weiner in South Africa, Bill Brandt in Scotland, Hans Namuth for art world portraits. He incorporated the cartoons of Ludwig Bemelmans, Ronald Searle, and George Giusti. Zachary claims credit for inventing a new photographic genre– the “environmental portrait,” in which a subject poses in the setting from which is power comes– as when Robert Moses stands on a steel I-beam suspended high above New York City, or Edward R. Murrow poses inside a control booth at CBS Zachary’s frequent favorites Slim Aarons and Arnold Newman used this approach on every possible occasion, even to the point of parody, as when an assignment in Africa sent Aarons to photograph white colonial rulers dressed for safari on their luxurious estates, while Newman photographed newly elected African politicians in business suits, or in remote locations, surrounded by their tribal family.

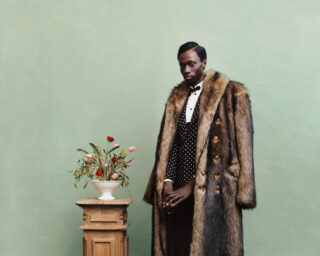

Photograph by Burt Glinn

Ted Patrick met Robert Capa around 1949, and soon after, Holiday became on of the Magnum agency’s steadiest clients. Beginning in January 1951, nearly every issue of the magazine included at least one story by a Magnum photographer. Burt Glinn, Elliot Erwitt, Dennis Stock, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Capa, and Ernst Haas contributed dozens of stories over the following two decades. On the surface, Holiday seems an uneasy match for Magnum’s mythic commitment to justice, the common people, and black-and-white photography. But Holiday suited Capa’s taste for travel and glamour, as well as his determination to create lucrative assignments for photographers. In Patrick he found an ideal patron– and poker partner. Patrick admired Capa, and in fact the entire organization, describing them in the pages of Holiday as “truly international, truly modern men… [who] had the world not only as their beat but as their living room. They were at home, sympathetically at home, wherever they opened their cameras and suitcases.”