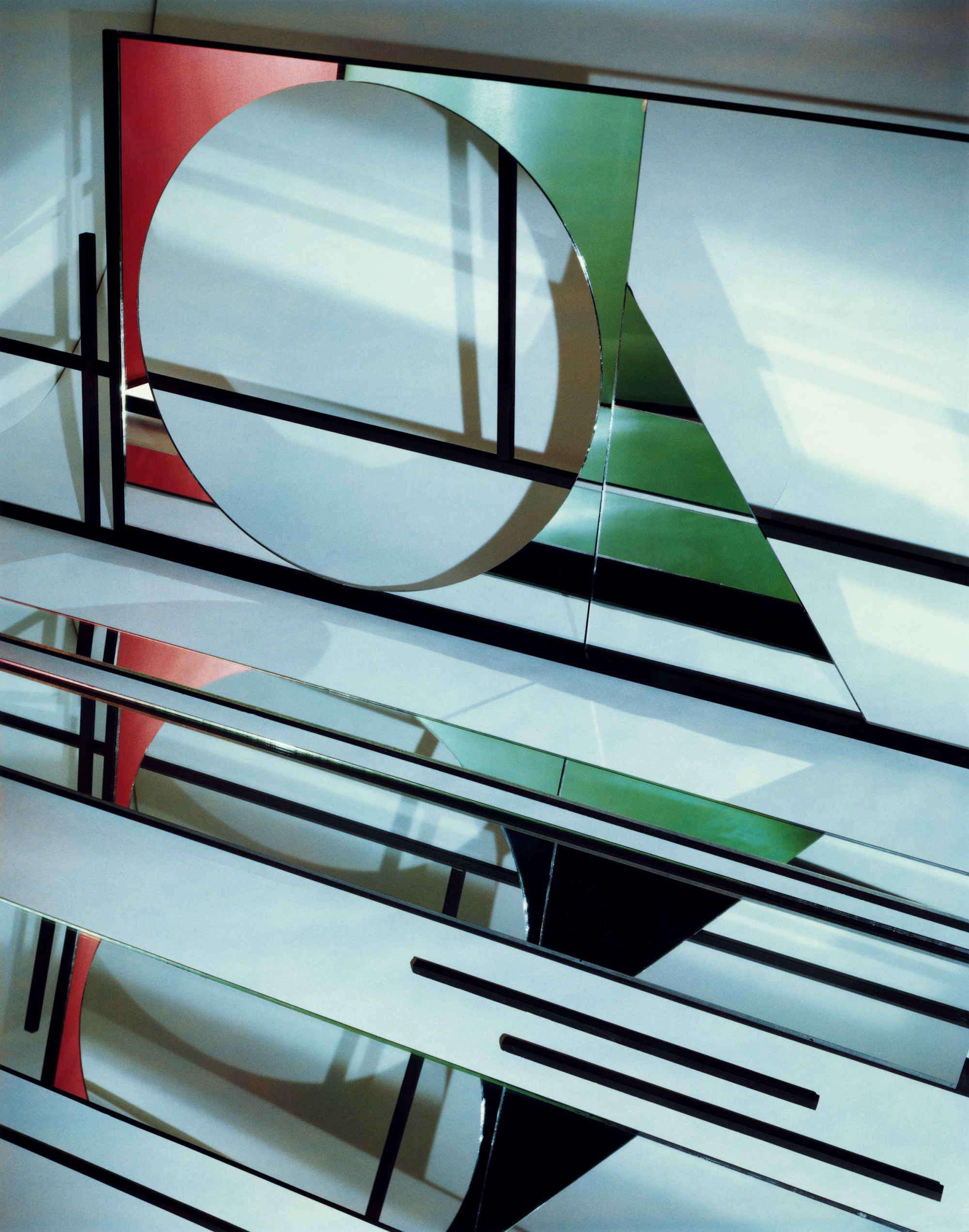

Barbara Kasten, Construct XI A, 1981

Courtesy the artist; Bortolami, New York; and Galerie Kadel Willborn, Düsseldorf

This article originally appeared in Aperture’s winter 2016 issue, “On Feminism,” under the title “On Defiance.”

In 1971, Linda Nochlin famously asked in the title of an essential essay, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” Lamenting the meager representation of women in art, she declared: “There are no women equivalents for Michelangelo or Rembrandt, Delacroix or Cézanne, Picasso or Matisse, or even, in very recent times, for de Kooning or Warhol.” In the heated debates of second-wave feminism, these dialogues were crucial and vital, and were essential to creating a more pluralistic narrative of art in the twentieth century. But those conversations rarely included photography—or film, or architecture, or design, for that matter—art forms that were other.

Photography is now our lingua franca—it is the dominant medium of our image-saturated era. Over the last half century photography has joined the ranks of painting and sculpture in the art market and the museum (this May, for instance, the newly expanded San Francisco Museum of Modern Art dedicated an unprecedented 15,500 square feet to photography). Recent years have also seen a spate of women-only exhibitions, including the Centre Pompidou’s 2010 elles@centrepompidou featuring works from their collection, the Musée d’Orsay’s Who’s Afraid of Women Photographers? 1839–1945 (2015–16), and Revolution in the Making: Abstract Sculpture by Women, 1947–2016 (2016) at Hauser Wirth & Schimmel in Los Angeles.

Courtesy the Getty’s Open Content Program

Despite exhibitions to further the visibility of women artists, many museums have fallen short of presenting balanced and diverse programs. In 2007, the Museum of Modern Art came under fire for its lack of female representation in its permanent galleries, with critic Jerry Saltz tallying a pitiful 3.5 percent of the art on view from their collection as being by women. But his numbers reflected displays from the collections of painting and sculpture only, not the collections of architecture and design, drawings and prints, and photography, where there were more works by women on view (although still not 50 percent). As a curator working at MoMA at the time, I was acutely aware of the imbalance, but dismayed by Saltz’s limited (and retrograde) view of art. In fact, MoMA was in the midst of organizing Pictures by Women: A History of Modern Photography (2010–11), an exhibition (of which I was a cocurator) that surveyed the history of photography with some two hundred works by women. This is all to say that even in the early twenty-first century, photography is still other.

This century has witnessed a boom of women artists investigating the possibilities of the photographic medium in new and exciting ways. Artists such as Liz Deschenes, Sara VanDerBeek, Eileen Quinlan, Miranda Lichtenstein, Erin Shirreff, Anne Collier, Mariah Robertson, and Leslie Hewitt all defy the dominant idea of a photograph as an observation of life, a window onto the world. While each artist possesses her own aesthetic language and artistic concerns, as a whole, their practices represent a look inward—to the studio, still life, rephotography, material experimentation, abstraction, and nonrepresentation. Driven by a profound engagement with the medium, these artists have created a dynamic domain for experimentation that has taken contemporary photography by storm.

© Berenice Abbott/Getty Images

It’s certainly risky to create a binary of “traditional” photography, which claims an indexical relationship to the world, versus the avant-garde tradition that considers the properties of photography itself: its circulation, production, and reproduction. As curator Matthew S. Witkovsky notes, “Abstraction … is not photography’s secret common denominator, nor is it the antidote to ‘traditional’ photography.” Recent scholarship has gone a long way to recuperate, and problematize, the status of experimental photography within photographic discourse. Nevertheless, throughout photography’s history, the avant-garde tradition has been considered an “alternate” to the dominant understanding of photography.

Can an argument be made that women have found fertile ground in the underchampioned arena of nonconventional image making? Have the historic marginalizations (of photography, avant-garde experimentation, and women artists) contributed to the vitality we see today? Can working against photographic convention, in a medium that is still sometimes considered other, be viewed as an act of defiance? It’s also challenging to make an argument based on gender (or race, sexuality, geography), since men have undoubtedly made accomplished work in the avant-garde tradition. Do we still need to discuss gender? Do we need exhibitions of women artists to shine the spotlight on underrecognized practices?

Courtesy the artist

I think so. At the time of this writing, Hillary Clinton has clinched the Democratic nomination for president, but the threat to reproductive rights and women’s scant representation in boardrooms and in government confirm that there is still much work to do. In the arts, there is marked gender inequality. Last year ARTnews cited the paucity of solo exhibitions dedicated to women in major New York museums (and for women of color, it’s even more dismal), and a 2014 study, “The Gender Gap in Art Museum Directorships,” by the Association of Art Museum Directors, reports that female art museum directors earn substantially less than their male counterparts. While there has been some progress since Nochlin’s rallying cry, the artists of this generation are more aware than ever of their roles in an imbalanced art world.

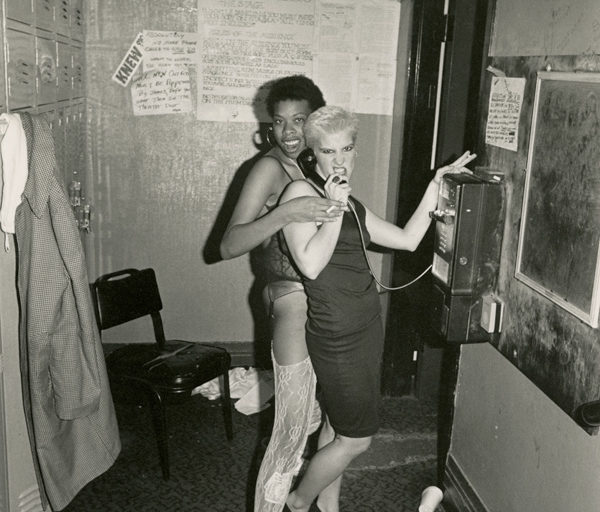

Photography has always been hospitable to women, and women have made some of the most radical accomplishments in nonconventional image making. It’s a relatively new medium, free from the crushing millennia-long history of painting and sculpture. In its infancy, photography was practiced by scientists and alchemists, not artists. A photographer didn’t have to be enrolled in the hallowed halls of the academy; she could cook it up in the kitchen. Victorian England saw the early botany experiments of Anna Atkins, narrative allegories by Lady Clementina Hawarden (featuring her daughters as sitters), and Julia Margaret Cameron’s purposeful “misuse” of the wet collodion process to create her signature portraits. The proliferation of mass media and new camera and printing technologies in the early twentieth century ushered in radical collages by Hannah Höch, Bauhaus experiments by Lucia Moholy and Florence Henri, and the modernist compositions of Tina Modotti. Some women worked in isolation, like Lotte Jacobi, who created her light drawings in seclusion in New Hampshire; others had patronage, such as Berenice Abbott, who was commissioned by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to make pictures of scientific phenomena. The postwar movements of pop art, land art, conceptual art, and performance art significantly incorporated photography—Hannah Wilke, Ana Mendieta, and Adrian Piper leaned heavily on photography, in all its uses. Their work is unfathomable without it.

Recent years have witnessed a generation of women exploring new ground in the photographic medium.

The experimentation, manipulation, and disruption of photographic conventions of the early twentieth century reached a crescendo in the century’s last decades. Art of the past forty years has set the stage for the dominance of contemporary experiments by women today. Since the 1970s there has been a plethora of women working in photography (some asserting they are artists “using photography,” not photographers), including Cindy Sherman, Sherrie Levine, Sarah Charlesworth, Louise Lawler, Barbara Kasten, Lorna Simpson, Barbara Kruger, and Carrie Mae Weems. These artists share an interest in the status, power, and representation of both images and women within cultural production. They collectively challenge the chief tenets of traditional photography—originality, faithful reproduction, and indexicality. While we now refer to many of the women of this time period as Pictures Generation artists, Sherman recalls, in a 2003 issue of Artforum, the unprecedented prevalence of female practitioners:

In the later ’80s, when it seemed like everywhere you looked people were talking about appropriation—then it seemed like a thing, a real presence. But I wasn’t really aware of any group feeling…. What probably did increase the feeling of community was when more women began to get recognized for their work, most of them in photography…. I felt there was more of a support system then among the women artists. It could also have been that many of us were doing this other kind of work—we were using photography—but people like Barbara Kruger and Jenny Holzer were in there too. There was a female solidarity.

These women embraced the expansiveness of photography’s parameters and have deeply informed, animated, and ultimately liberated the work of the artists who came after.

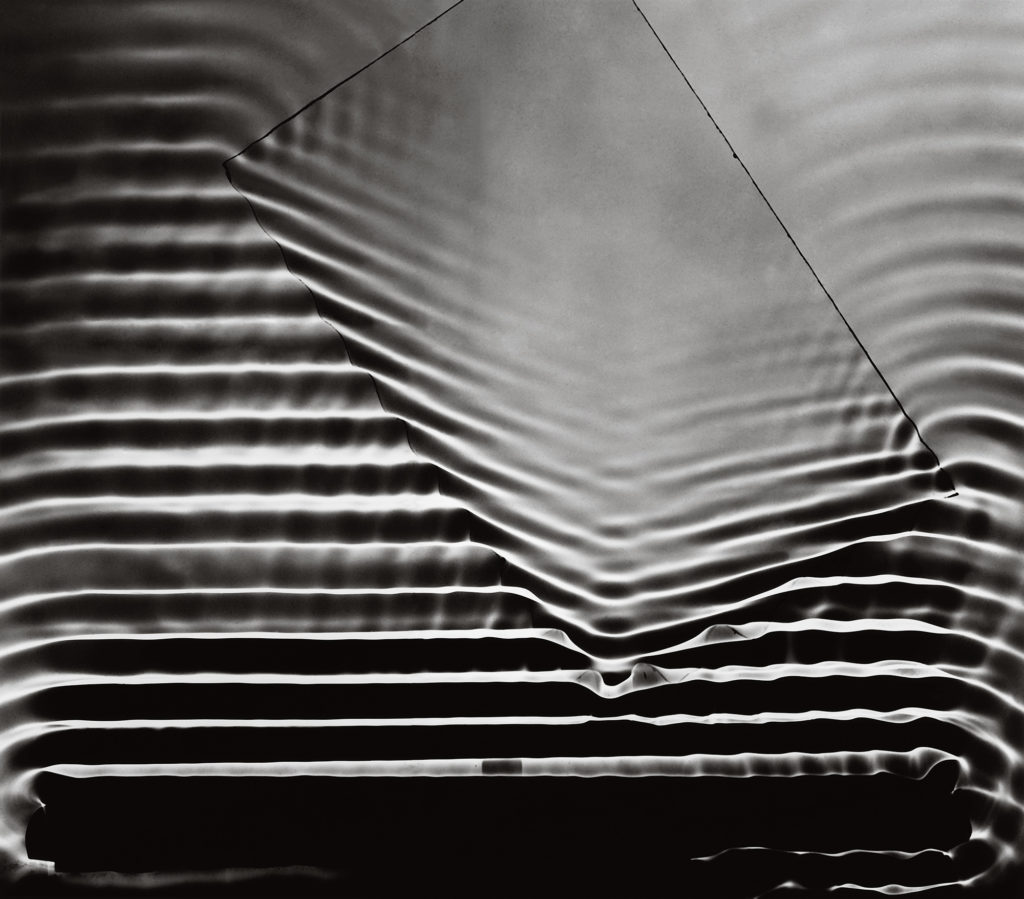

Courtesy the artist, MASS MoCA; Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York; and Campoli Presti, London/ Paris

Recent years have witnessed a generation of women exploring new ground in the photographic medium. I spoke with several of them for this article. Liz Deschenes, whose work sits at the intersection of photography, sculpture, and architecture, is central to current conversations around nonrepresentational photography. Working between categories and disciplines, Deschenes is also deeply rooted in the histories of photographic technologies, challenging the notion of photography as a fixed discipline. Deschenes questions and resists all power structures, including binaries that confine works of art. Photography is frequently reduced to polarized classifications—color versus black and white, landscape versus portrait, analog versus digital, representation versus abstraction. As an educator, she underscores the medium’s fluidity by introducing disregarded figures (often women) and so-called alternate histories into her teaching. Deschenes explains:

It does not make much sense for women to follow conventions. We have never been adequately included in the general dialogue around image production. I think women have carved out spaces in photography because for such a long time the stakes were so low or nonexistent, that there was no threat of a takeover. I believe that has shifted with the female-dominated Pictures Generation.

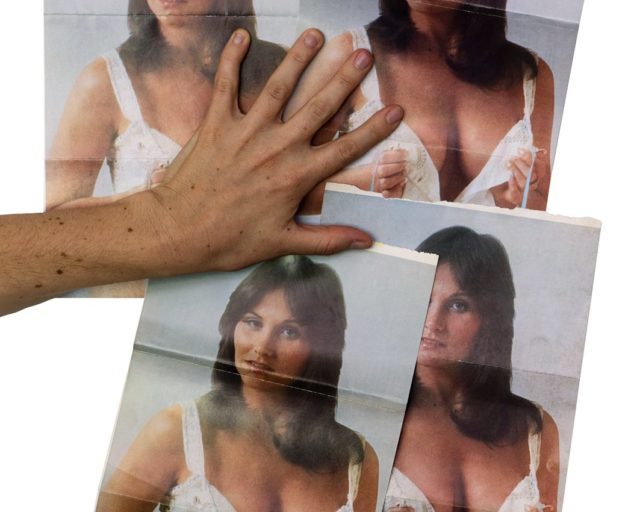

Miranda Lichtenstein, whose lush images have revived the contemporary still life, similarly cites the influence of the Pictures Generation on her work:

I began working in nontraditional ways with photography because I wanted to push against the images around me (particularly of women). I used collage and alternative processes because it allowed me to transform and control the pictures I was appropriating. I studied under Joel Sternfeld, so “straight photography” was the dominant paradigm, but I was lucky enough to see work by women in the early 1990s that had a dramatic impact on me. Laurie Simmons, Sarah Charlesworth, Gretchen Bender, and Barbara Kruger were some of the artists whose work cleared a path for me.

Courtesy the artist and Metro Pictures, New York

As Lichtenstein suggests, these women opened avenues for new ways of observing and interrogating the image in today’s culture. In the digital age, where photographs are most often images (that is, JPEGs and TIFFs, not prints), Lichtenstein, Deschenes, and others affirm the material properties of the medium and contribute to a more malleable idea of photography within a historical continuum.

Photography’s history and its relationship to sculpture, media, and film technologies are central to Sara VanDerBeek’s work. Through carefully calibrated photographs of her own temporary sculptures, neoclassical sculptures, ancient edifices, and architectural details, VanDerBeek has developed an aesthetic language that deftly prods the relationship between photography and sculpture. In addressing the history of sculpture, she shifts a mostly male- dominated history into a contemporary female realm, where object and image are leveled. VanDerBeek, whose recent art addresses “women’s work,” remarks:

This sense that there is a quality of impermanence to our progress [as women] leads me to photography. Specifically I’m referring to its expansive and elastic nature, its space for experimentation and its “democratic” nature. Photography has always been open to diverse practitioners and throughout its history it has included the possibility for expression for many who were not easily allowed into other arenas. I think some of this does come from its status as “other,” and perhaps, for me, even more so from its interdependent relationship with mass media and technology.

Courtesy the artist and Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York

Eileen Quinlan, whose photographs are grounded in material culture, the history of abstraction, feminist history, and, most lately, the ubiquity of screens, cites the predominance of conventional photography curriculums as fomenting a type of resistance:

Photographers have always created constructed, nonobjective, and materially promiscuous pictures. But this history isn’t taught, and if it is alluded to, it’s mentioned derisively. Photography remains a male-dominated field, both in the commercial and fine art sectors, and is saturated with “straight” photographers who supposedly harness the medium’s “strengths,” that is, the ability to sharply and irrefutably record and depict a kind of truth about the world. Maybe women sense that taking unconventional approaches to photography will somehow afford us more room to move? Jan Groover was political when she made abstraction in the kitchen sink. Working with still life, setup, or self-portraiture isn’t only about investigating interior or domestic worlds, either. Women are more sensitive to the potential for exploitation when we photograph others … as an artist I am consciously rejecting much I have been taught about pure photography as observation of reality. I understand all photographs to be made rather than taken or found.

Courtesy the Estate of Sarah Charlesworth and Maccarone

Many of these female artists are educators, and in some cases their roles as teachers can be profoundly impactful. Deschenes asserts, “There is no domain within higher photography education that does not have a male authority and history inscribed in its hierarchies, curriculum, alumni, buildings, and more. To attempt to subvert any of that is certainly a political act.” Perhaps the most important figure in this regard is Charlesworth. Deeply respected by younger artists (she is cited as an inspiration by those quoted here), Charlesworth created a vital link between her generation and the next. She taught, wrote about, conversed with, and empowered a new generation of artists working in experimental ways, who, in turn, have made community and dialogue central. Through her own groundbreaking work and her strong desire to build community among women artists, Charlesworth established a space for diverse photographic practices to flourish. Her advocacy for the medium and its continuation today by Deschenes, Lichtenstein, Quinlan, Hewitt, and VanDerBeek, who teach at prestigious schools, has unquestionably influenced the course of photographic history and how it is taught.

Like their work, each artist under discussion presents a different viewpoint on photography and so-called experimental practices. However, together they affirm that the medium has always been fluid and resistant to typologizing. Through exhibiting their work, teaching, publishing, and public and private conversations, these artists celebrate the inherently hybrid, pluralistic, and mutable nature of photography, within a robust space for dialogue, debate, and, I would posit, defiance. As a curator who has worked with many of these figures, I have witnessed artists creating work, meaning, and community in arenas long hospitable to women but outside the mainstream, marshaling a shift from the periphery to the center. Artist Emily Roysdon, in the 2010 catalogue Modern Women: Women Artists at the Museum of Modern Art, perhaps expressed it best: artists today are not “protesting what we don’t want but performing what we do want.”