How a Museum’s Photographic Archive Honors Generations of Chinese American Lives

After a devastating fire in early 2020, the images in the Museum of Chinese in America’s collection continue to tell a story of resilience.

Bud Glick, “Big Tall” (Gao Da) Chin at Sam Wah Laundry, Bronx, 1982

Courtesy the Museum of Chinese in America

In late January 2020, as a fire tore through the building at 70 Mulberry Street, in New York’s Chinatown, the staff of the Museum of Chinese in America feared the worst. They watched from a park across the street as firefighters worked deep into the night to contain the blaze. This five-story corner building was once a schoolhouse; now it housed a dance center, a senior citizens’ center, a vocational training office, an athletics association, and the museum’s off-site collections. Luckily, there were no fatalities. By morning, the building was a smoldering husk, and it would be weeks before they would be allowed back inside. Many figured that if the fire hadn’t ruined the collection, then all the water surely had.

Courtesy Wally Wong

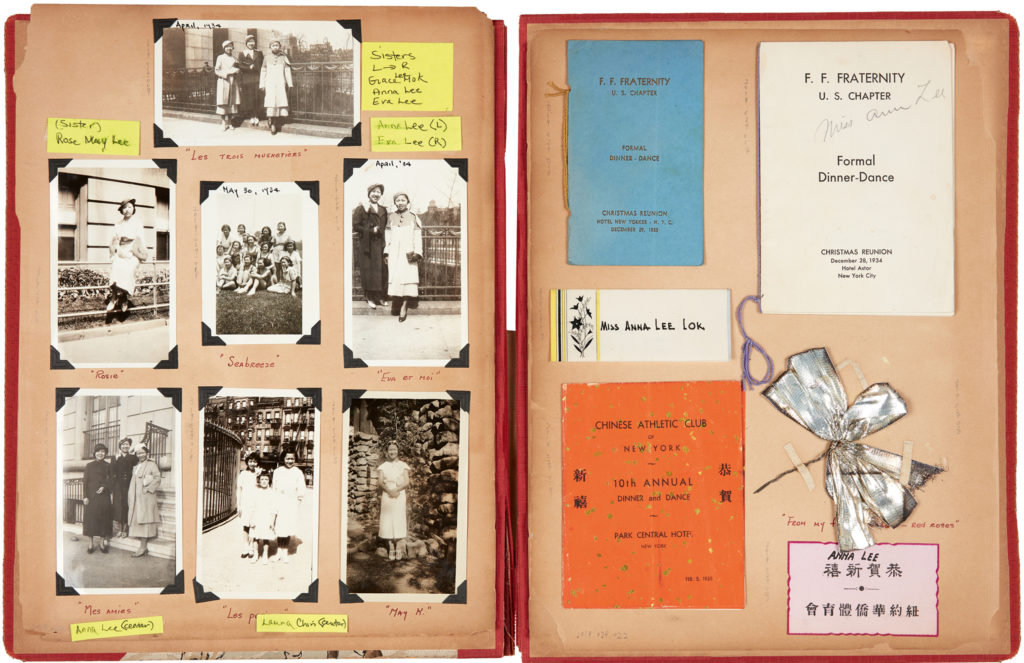

The museum, located a few blocks away on Centre Street, was started as a salvage operation of sorts. In the late 1970s, Jack Tchen and Charlie Lai began noticing all of the stuff old-timers were leaving out on the streets as junk. Luggage, clothing, personal papers, things that had outlived their usefulness. But Tchen, a historian, and Lai, a community organizer, saw these items as part of a broader history. Perhaps whoever owned this old suitcase or sheaf of menus never perceived themselves that way—as having a history, or participating in a broader story of belonging, let alone an American one. What began as Tchen’s and Lai’s dumpster diving resulted in a museum that today contains some eighty-five thousand items. They are random items, yet they collectively articulate the diverse experiences of Chinese in America.

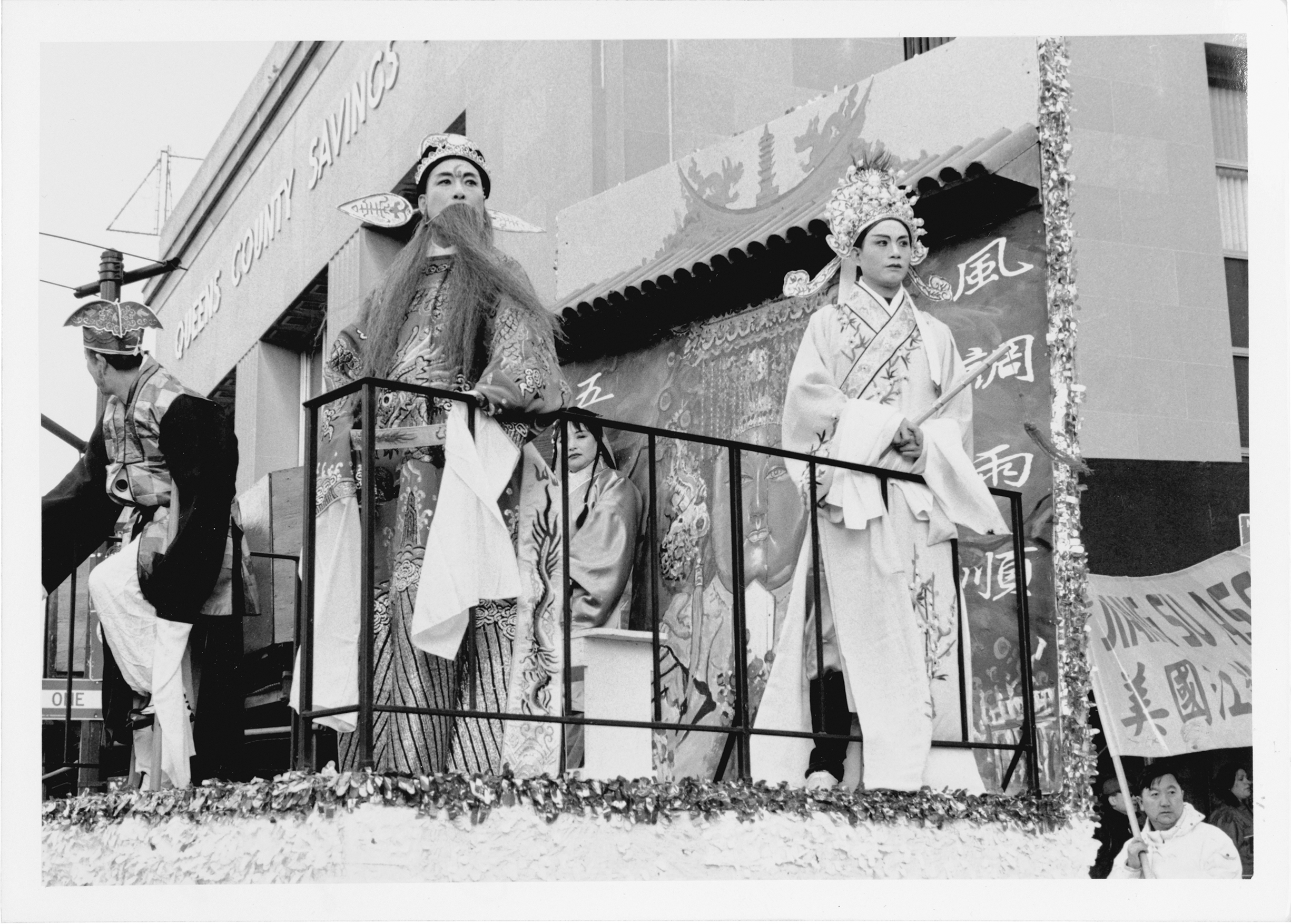

In the months following the fire, curators and archivists were allowed to reenter 70 Mulberry. Somewhat miraculously, the bulk of the collection could be restored and saved—T-shirts, concert posters, hand-painted signs, old passports and immigration documents, paper fans, cigarette cartons. These are items which might be worthless in purely monetary or market-driven terms. Yet they are irreplaceable, indexing immigrant histories, traditions, and practices that have yet to be written. Very few of these objects were meant for archival preservation. Old signage or furniture once served a primary function for the nearby merchants who couldn’t understand why a museum would want such things. Instruments were meant to be played. Costumes were for performance. Irons and washboards were merely tools of the laundryman’s trade.

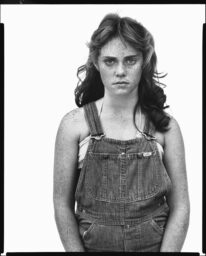

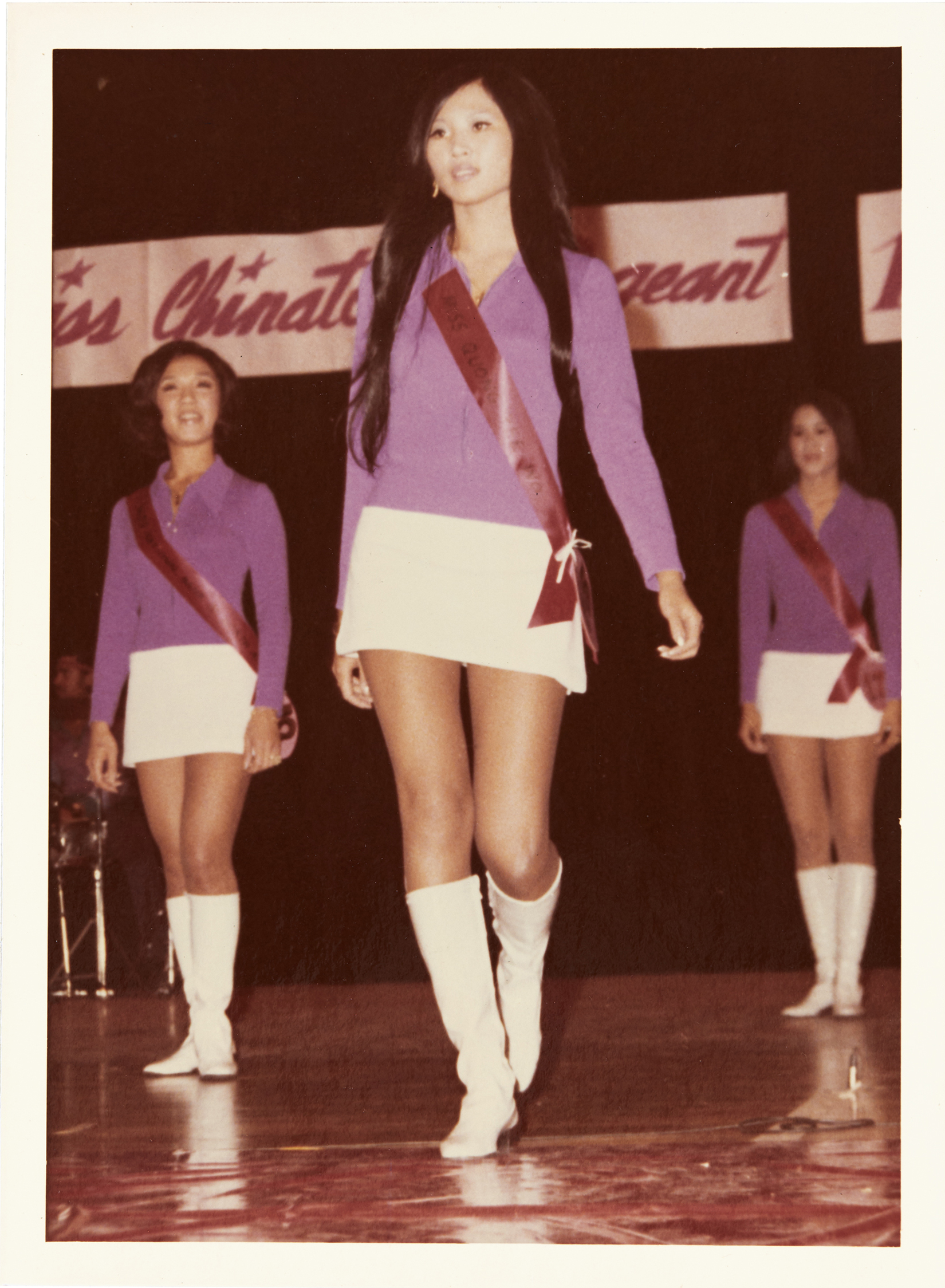

Courtesy Alison Shue Lee

Unlike other parts of the collection, the museum’s holdings of photographic prints, slides, and negatives communicate a clear desire to leave something behind, despite the lingering possibility that the people on both sides of the camera may have regarded this U.S. chapter of their lives as a temporary, transient one. These images articulate aspirations or desires that the subjects themselves might not have felt brazen enough to speak aloud: the family looking their spiffiest for a holiday portrait; professional headshots for modeling or singing gigs; school children obediently reciting from their workbooks; the tourist measuring himself in front of a statue of some supposedly great American. There is a photograph of the Chinese Musical and Theatrical Association, which opened on Pell Street in 1931. Associations such as this one functioned as community centers and schools, ways of maintaining a tie to centuries-old traditions of storytelling and performance. In this photograph, taken at a fundraiser in 1946, the performers huddle together onstage. Some radiate pride, smiling, sitting up as straight as possible. Others look shy or uncertain; perhaps they’d prefer to have a picture taken without all this makeup on. They are flanked by performers holding Chinese and U.S. flags.

Courtesy the Museum of Chinese in America

While studying at Juilliard, Mary Mon Toy was told that an Asian could never become an opera singer. There is a studio portrait of her from the 1950s, when Mon Toy had defied expectations to become a pioneering Asian American performer on Broadway. A finger is pointed artfully toward the sky; she gazes far past the photographer. Where will her vision take her? I’m particularly drawn to a photograph of Stephen Cheng, an idealistic singer who, in the 1960s and 1970s, sought to connect the United States and China through a fusion of jazz, rock, and Chinese traditional music. He even dabbled in reggae. In one of the only surviving photographs of his band, the Dragon Seeds, from a 1971 concert at the Museum of Modern Art, Cheng appears to be swaying to a groove, eyes and wide smile conveying a sense of bliss, as his band plays behind him.

In the United States, whites first encountered Chinatowns in major cities in the mid-1800s and early 1900s as an exotic, potentially dangerous portal into other worlds. In the early twentieth century, there were best-selling guidebooks about the savagery and old-world quirks of Chinatown in San Francisco and New York, as well as “slumming tours” that brought daring tourists down dark alleyways, past knife-wielding gangsters, and into opium dens. Some of the most famous images of San Francisco’s Chinatown, from the 1890s and into the first decade of the twentieth century, were taken by Arnold Genthe, a German-born photographer who lived and worked there at that time. He often hid his camera from sight as he took photographs so as not to be noticed by the locals. Yet his work presented a skewed version of immigrant life. He frequently cropped out the presence of Western culture, such as white people or English-language signs or advertisements, in order to preserve an alien, inscrutable quality in Chinatown.

Courtesy the Museum of Chinese in America

Courtesy the Museum of Chinese in America

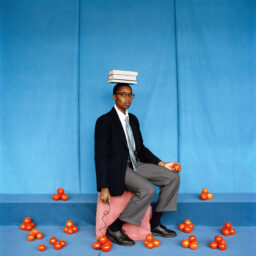

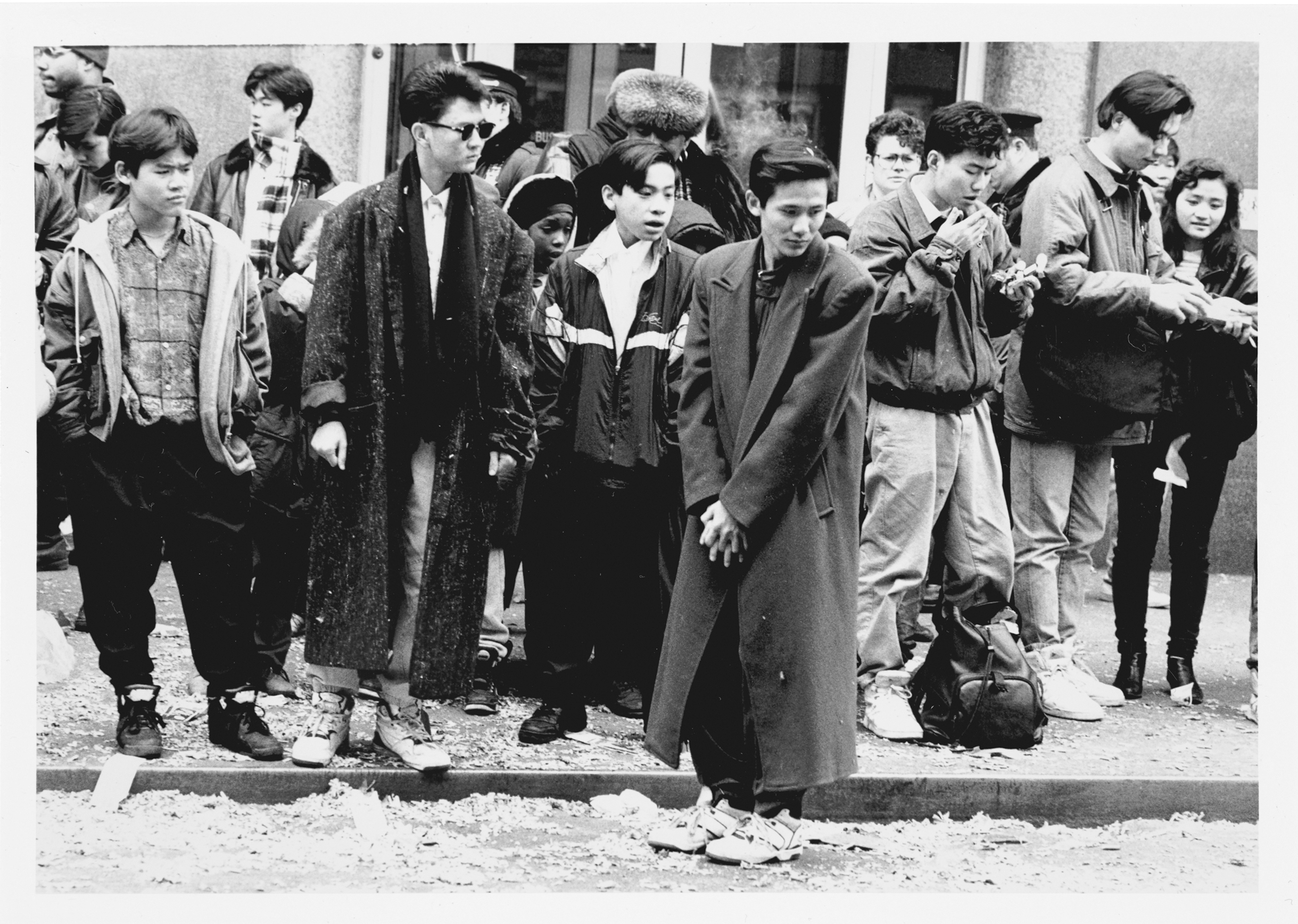

As various waves of immigrants slowly adjusted to life in the United States, the reality was often more mundane than those sensationalistic representations from the past. In the early 1980s, Bud Glick began taking pictures around Chinatown as part of the New York Chinatown History Project. His images document the neighborhood’s shifting generations, as the old-timers were passing on, and younger folks, horsing around with Black and brown neighbors, or posing in their punk-rock T-shirts, were beginning to explore new identities. In one of Glick’s pictures, a middle-aged woman at a laundry stares off into the distance, a moment’s reprieve during the busy workday. She leans on the counter and looks as though she is in a trance. Is this the life in the United States she once dreamed of? Among the collection’s newest acquisitions is a portfolio of 2020 images from Mengyu Dong documenting Chinese American communities participating in Black Lives Matter protests. Dong follows a group of young activists at a march in Washington, D.C. Their bilingual signs blend into the broader landscape of protest that these images depict. But they hint at how this community will continue to change and evolve from within.

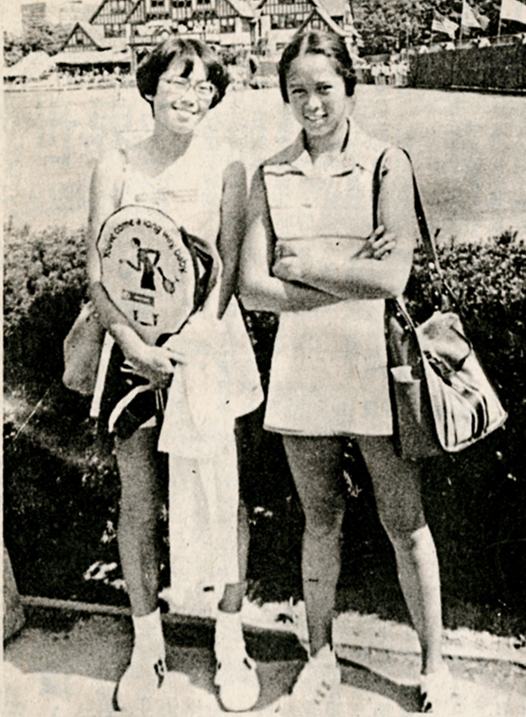

There is a photograph of the Chinese American tennis player Marcie Louie at the U.S. Open in 1977. It’s unclear whether she’s competed yet. She hugs her racket and smiles. She is with her younger sister, Maureen, who will eventually become a tennis pro too. But Maureen’s arms are folded, and her grin is a bit harder to read. She looks impatient. Perhaps she is tired of being photographed. Maybe she’s just not accustomed to it yet. It reminds me of how tedious it felt to pose for my parents’ pictures when I was a child. I couldn’t understand why we needed so many pictures.

A few years ago, I began collecting photographs of Asian American life. As with any excursion into found materials, I was drawn by the storytelling questions that emanated from these scenes of mustached teens waiting for a movie; kids on a playground beating up a peer; a seemingly generic family portrait, only the father is dressed like a greaser. Who were these people? Where did they live? Did they get along with their neighbors? What did they imagine, if they allowed themselves that privilege? My collection involves an element of fantasy, too, a naive hope that I would reconnect with honeymoon photographs my parents lost when they were new to this country.

Courtesy the Museum of Chinese in America

Courtesy the Museum of Chinese in America

For those from the Chinese diaspora who came to the United States in the twentieth century, photography was a tool for imagination and self-fashioning. It holds a special status in the inventory of immigrant things—a way of stopping time, commemorating one’s presence, perhaps capturing a snippet of one’s new life that can be mailed back to everyone across the sea. Especially in the predigital age, photography recorded a sense of acculturation, expressing a desire to register your presence in front of a national landmark or a momentous scene. A sense that you would someday look back, once you had the time. Perhaps it becomes art or a statement about history only to the later generation. In the moment, it’s just a desire to stand in front of the statue or totem that everyone else is standing in front of.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 242, “New York,” under the title “Voices & Memories.”