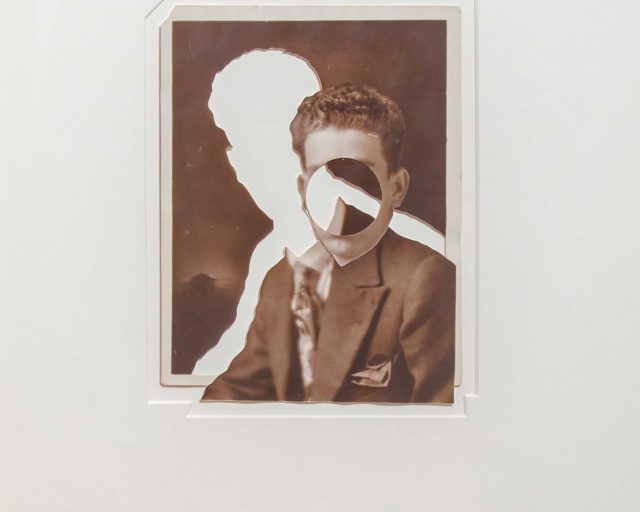

Alice Rose George, New York, 2012

Photograph by Susan L. Stewart

Perhaps the clearest picture of Alice Rose George, beloved editor, curator, teacher, and poet, who died on December 22, 2020, in Los Angeles at the age of seventy-six, can be seen through her own eye, connecting—as she so innovatively did in the books and magazines where she made her mark—all the seeming and revelatory contrasts of her life.

George’s mother was an accomplished pianist who taught her daughter to play Robert Schumann and Frédéric Chopin; her father, who called her “Sweetie Pie,” liked to sing her the 1919 song “Alice Blue Gown,” about a girl heading to town in her silk dress. After George left rural Mississippi in the 1960s, she whittled her nickname down to “Pi,” got a job in the photo department at Time and, eventually, landed the extremely New York City address of 1 Fifth Avenue—“It was impressive, and so were the drinks, which were stiff,” recalled Jim Goldberg, one of the many photographers she either mentored, taught, edited, or otherwise worked with in her lifetime.

George helped shape a pivotal visual era in publishing. “It was the eighties, a time when magazines were king,” said Catherine Chermayeff, now director of special projects at Magnum Photos, whom George hired when she worked at Fortune. “I didn’t have women as role models who had important jobs. Alice was magical to me; she had a very confident eye, which I respected and copied.”

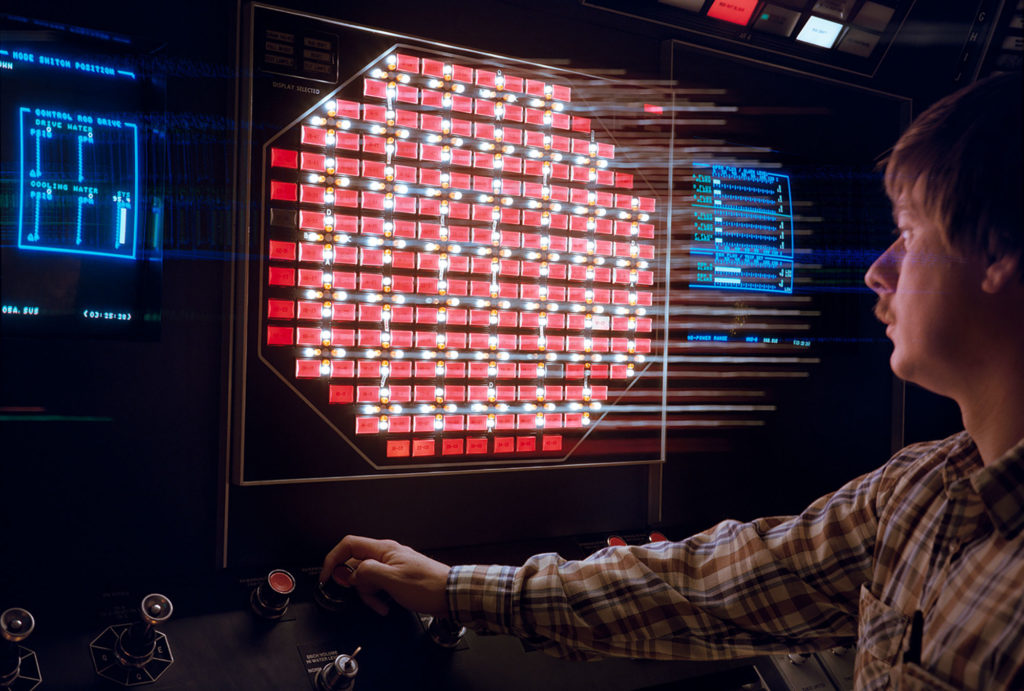

Mitch Epstein was among the unlikely photographers George commissioned to shoot business stories at Fortune—along with Nan Goldin, Peter Hujar, Duane Michals, and Gilles Peress—prioritizing art over technical expertise. George sent Epstein to shoot a story on nuclear power plant control rooms. “It didn’t matter to her that I had no experience shooting industrial environments, and no lighting prowess,” he said. “She was the rare picture editor who appreciated photographers for their idiosyncratic sensibilities.”

Just prior to her job at Fortune, George was photo editor at the short-lived but influential Geo; she would go on to work for Magnum Photos and Details, and as publisher of the literary magazine Granta, and she was an instrumental consultant for other publications, including Aperture magazine. She curated a series of books for Damiani, consulted for private collections, and edited or coedited five books of photography, among them Hope Photographs (1998) and Here Is New York: A Democracy of Photographs (2002), an 864-page celebration of the city which grew out of a grassroots exhibition George organized with Peress after the 9/11 attacks.

I must have met Alice Rose George around 1999. This was at DoubleTake, another short-lived but deeply influential magazine, a literary and photographic quarterly housed at the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina. At DoubleTake, words and images were seen as collaborative equals—neither existing to literally depict the other. Even as a young intern, this was exciting to me; and while I was officially working with the fiction editor, I wanted to learn about everything. When Alice came to town, I was allowed to sit in on a couple of her marathon editing sessions—Polaroids of various sequences, prints spread all over the floor of the photo office, lunches ordered in, as Alice, soundtracking these scenes with her infectious laughter, unearthed incongruous, perfect connections in work by both famous and almost totally unknown photographers. In those brief encounters and in the pages that emerged, I witnessed how Alice, the poet, was able to see photographs as texts, words as pictures.

In the last year of George’s life, her partner, Jim Belson, witnessed those same layouts on the table at home in New York and, after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, in Los Angeles. Photographers continued, as they had always done, to send her their work. “She had this uncanny vision about sequences,” Belson told me. He and George had first fallen for each other in 1975 at a reading on the Upper West Side, reconnected in the mid-’90s, but they lived on opposite coasts and lost touch. Eight years ago, on a trip to New York, Belson was sitting in Washington Square Park, when he impulsively looked up George online and sent her an email, unaware that she was still living half a block away. “Now I know why I created that website,” she said when they were finally reunited.

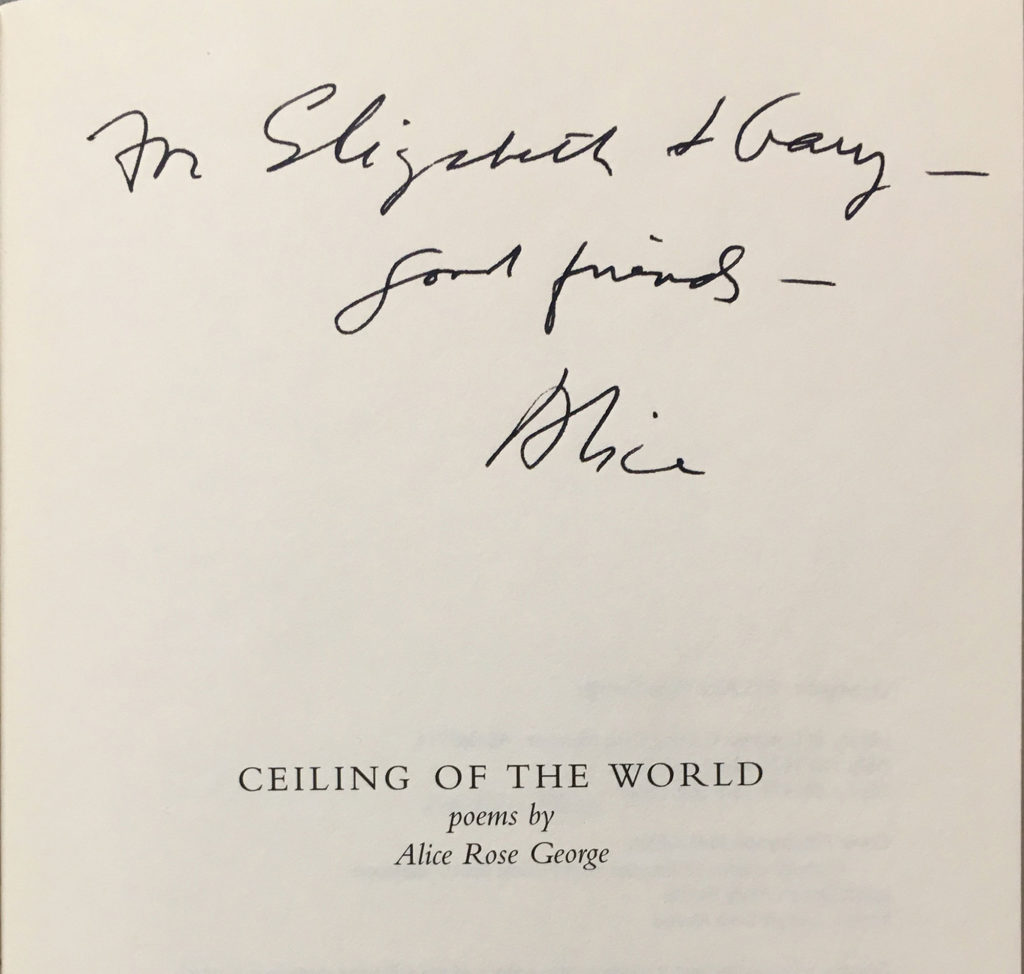

George was a writer first and a raw and visceral poet always, even and especially when it came to photography. George’s poems—collected in Ceiling of the World (1995) and Two Eyes (2015)—appeared in Bomb, the Paris Review, and the Atlantic. In “What Is Beautiful,” the title’s question turns explicitly to the relationship between words and images:

Later, pages turned down, she said,

“It is words.” The most beautiful

thing in the world. “But they aren’t visual.”

“Yes they are.” Without meaning to

he slammed the book shut, started a fire.

They sat face to face.

Here, friends and colleagues, editors and photographers remember Alice Rose George.

Photograph by Daniel Reuter

Melissa Harris, editor-at-large at Aperture Foundation

Alice was remarkably generous. She was generous with young photographers, and she was generous with her colleagues and collaborators.

We met sometime in the 1990s, a few years after I joined Aperture, but it wasn’t until later, when we became neighbors in the Village, that we really got to know each other. Over long dinners at the Knickerbocker, we discussed photography, but also her first love, poetry, as well as music, and her Mississippi roots. There was something charmingly Southern belle-ish about Alice—the grace in her gestures, the lilt in her voice—which became wonderfully apparent to me when I once saw her bantering with William Eggleston. And she had street smarts along with a full-throttle laugh. Occasionally, we ran into each other in Washington Square Park—Alice walking her Shiba Inu, Iko, and me walking my Lhasa Apso, Ella. Sometimes, the two of us would see Mary Ellen Mark on her regular walk around the park with her husband, Martin Bell. Given Mary Ellen’s over-the-moon-ness for dogs, those serendipitous occasions were especially festive.

Alice went out of her way to help emerging photographers, and to advance the medium in which she had invested so much of her heart, mind, and time. Countless photographers went to her for her fine eye, and she helped edit and sequence their projects. Because of her open spirit, how much work she saw and, most importantly, how much I respected her sensibility, when I became Aperture magazine’s editor-in-chief, I invited her to join the editorial advisory board (which later evolved into a stellar group of contributing editors). It was largely because of Alice’s involvement with us, and with Howard Stein’s remarkable organization Joy of Giving Something, that Aperture was able, for the very first time, to commission large-scale photographic stories. We published the first of three commissions—British photographer Jason Florio’s exploration of the “new” Libya—in 2004. Supporting a photographer’s dream project was something we’d always hoped to do, but had never had the means to until then. Without Alice, this unique opportunity would not have been possible. We will always be grateful to her.

Courtesy the artist

Susan Meiselas, photographer and president of Magnum Foundation

Alice had what I called an “authored eye.” She challenged the kind of old magazine photojournalistic framework that meant hiring people to illustrate the ideas of the world as the powers that be wanted to present it. Early on, she understood this shift. You see an expression of it in her work at Geo and Granta, for instance, and in so many books and exhibitions, and her work in supporting collectors.

Fred Ritchin, dean emeritus of the International Center of Photography School, New York

Being a picture editor could be somewhat of a grim business due to the pressure of deadlines and the harrowing photos one often had to look at. Being a picture editor in the 1970s, when I first met Alice, was an extraordinary and impactful position, given the renaissance in photojournalism that occurred in the years after the weekly Life magazine went out of business. Alice was prominent in the field, a major force and a leader, empathetic and open to new ideas.

In 1978, she and I both applied for picture editor positions at Geo and the New York Times Magazine. She got the job with Geo, and I went to the Times. Our paths crossed and we remained friends. She held many positions at major publications, but I remember her especially for her continuing generosity with photographers, helping them to edit their personal projects, often, as I understood it, simply out of friendship. She continued to write poetry, and she began to teach, finding a new equilibrium, even as the industry in which she had played so much a part had constricted. I will miss her laughter, her energy, her warmth, and her discerning eye. She helped to define an era.

Philip Gefter, author and photography critic

I worked with Alice at Fortune in the 1980s. Fortune had a tradition of using photographers well—including Margaret Bourke-White in the 1930s, and Walker Evans as picture editor in the 1950s. I felt a kinship with Alice, as we shared a similar visual sensibility and a mutual intention to advance that august tradition in photojournalism in a way that would take the history of photography forward.

Alice established a periodic photographic feature called the Fortune Portfolio, a platform for visual documentation and storytelling and an opportunity to allow photographers to do in-depth picture essays. The range was broad and a lot more fun than one would expect from a sober business publication: one, for example, was about the construction of satellites that were being sent into orbit at the beginning of the technological revolution; another chronicled the shoot for the first MTV video with Madonna in Venice. Alice would go to battle with the editors to secure ten pages for the pictures, if necessary. She was a champion of photography. She had imagination, spirit, commitment, and a vision.

Nan Goldin, photographer

I can’t imagine the photo world without Alice. She was one of the pillars. She gave me my first commercial job at Fortune in the ’80s, photographing Paul Newman at the Detroit Grand Prix. She was shocked that I didn’t have a credit card or a driver’s license, but she understood my lifestyle. We always had fun together in and out of bars. She’ll be much missed.

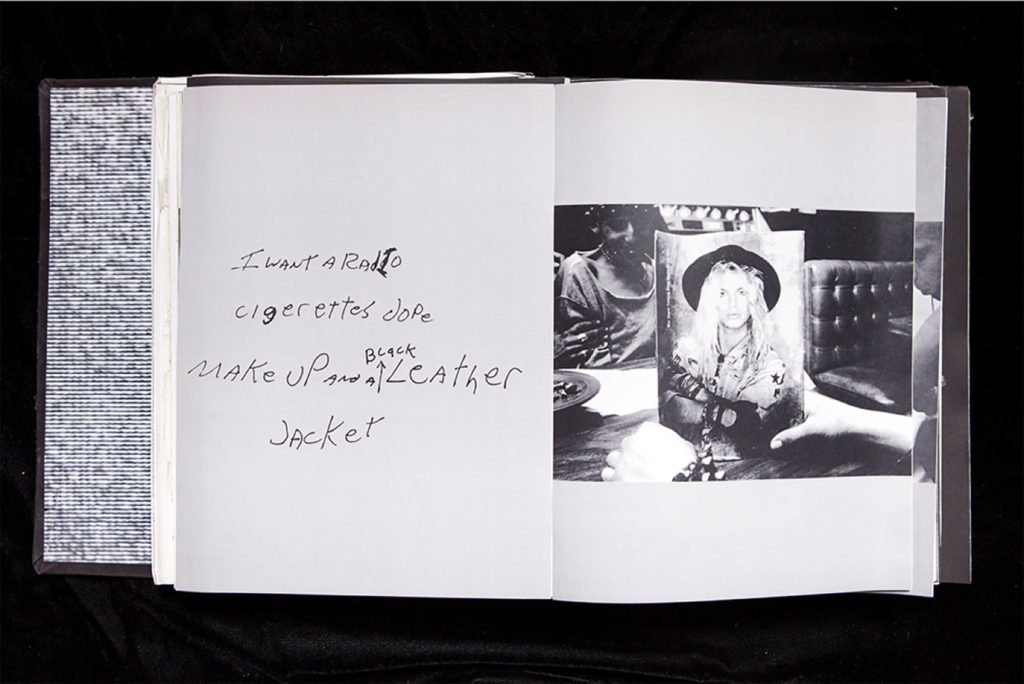

Courtesy the artist

Jim Goldberg, photographer

Alice was part of a group of people I would send maquettes to when I was working on what would become the book Raised by Wolves (1995). She would talk about picture relationships and how images could elicit thoughts and memories and stories, and the way I was using text in combination with photographs. I think she felt aligned with that, and also with this idea of playing with truth and playing with documentary. I think that’s what she liked about words—that they could be open and not didactic.

Alec Soth, photographer

Every year, I looked forward to seeing Alice as a fellow faculty member in the University of Hartford MFA program. Alice was worldly and cosmopolitan, but her Mississippi roots ensured she was equally warm and easygoing. She was also funny as hell. She never let me forget the time I managed to get us wildly lost in Connecticut while attempting to bring her back to her hotel in downtown Hartford. Recently, I spent time with Hope Photographs, a book Alice edited in 1998 along with Lee Marks. It feels appropriate to mark Alice’s passing with this book’s spirit of hope and gratitude.

Courtesy the artist

Alex Harris, photographer

Alice entered our lives at just the right moment in 1995, here in North Carolina, to help us create and launch DoubleTake magazine and to edit books under the DoubleTake imprint. It is one thing to edit a monograph, but another altogether to create a mosaic of disparate voices—this was Alice’s specialty—to delight us and engage our imaginations.

For a magazine devoted equally to the written word and visual image, where writers and photographers had equal weight to wander and wonder, it made sense that DoubleTake would turn to Alice, who brought her poet’s eye to her work as our photography editor. As a poet, Alice believed in the power and necessity of words, but she also knew the world is more complicated than anything you can say about it. That’s where Alice—and photography—came in.

Alexa Dilworth, publishing and awards director and senior editor of CDS Books at the Center for Documentary Studies, Duke University

I liked Alice a lot; she was dry and easygoing and smart and irreverent. I was the managing editor of DoubleTake, and I was working from home and both of my kids were with me (they were maybe two and four—some deeply needy age), and I must have been on a landline with a very long cord, as I was in the bathroom with the door locked talking to Alice about page proofs. I had gotten into the bathtub and had pulled the shower curtain across (like that would help with muffling sounds!). The kids were banging on the door and screaming for me to come out—it was one of those standard working-mother squeeze plays. I was going to go check on them, and had asked Alice to hold, when she said, “Wait. If they’re knocking down the door, we know they’re alive, so let’s keep working until they go quiet.” We both laughed pretty hard at that. We kept going through the pages with a nonstop din in the background.

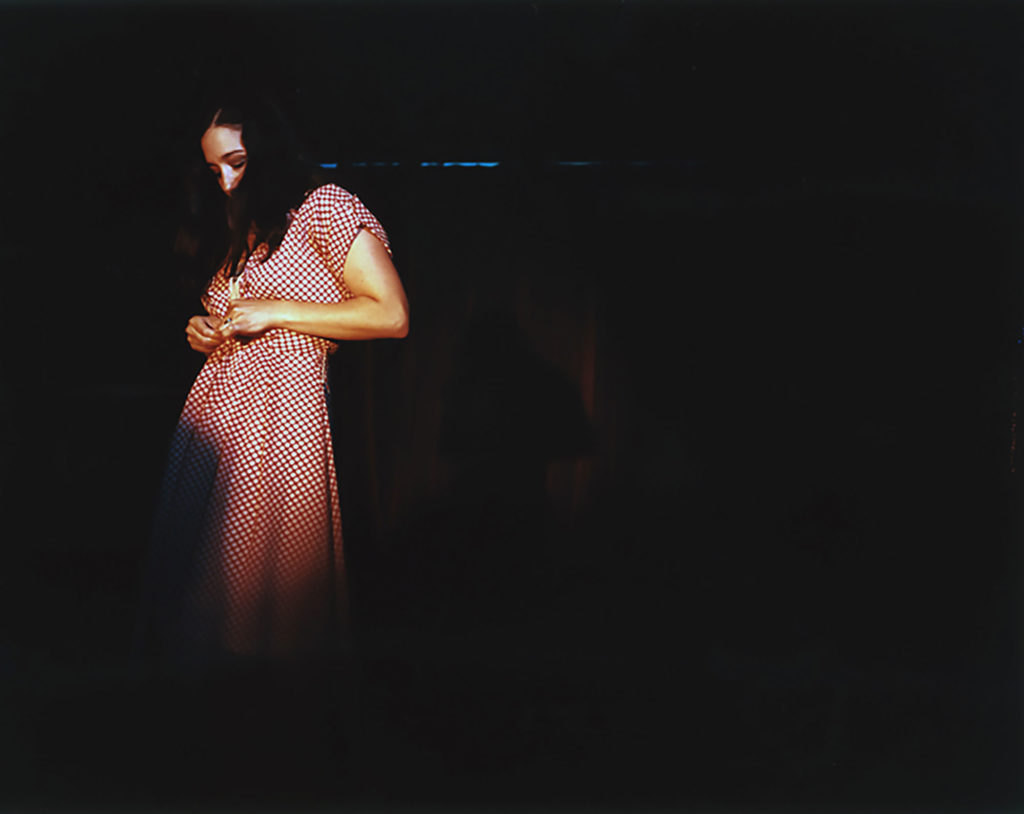

Courtesy the artist and Yancey Richardson Gallery

Lisa Kereszi, photographer and critic and director of undergraduate studies at the Yale School of Art, New Haven, Connecticut

We met two years after I graduated from college in the late ’90s, when I had begun working as Nan Goldin’s assistant. I don’t see how I would have had any monographs published without her steadfast support. She understood what I was trying to do with the joining of two bodies of work (strip-club interiors and New Burlesque dancers) in the book Fantasies (2008), and understood that it was not a documentary project, but a poetry of juxtaposition offered up to the viewer. I otherwise would have felt a bit off-base or just plain wrong in combining the two, but she felt strongly that it worked on many levels, which gave me the confidence to proceed.

Nelson Chan, Carl Wooley, Tim Carpenter, and J Carrier of TIS books

Alice was our teacher. More than anything, working with her made you tough. Her particular gift was for making a book work, more as a partner than as an editor, through close reading of the pictures. Alice would pore through stacks of prints as if putting together a puzzle; she had a formidable memory for many rounds of edits, the placement of a single picture. Her insistences were gentle but unambiguous.

We are publishers, in part, because of the example of Alice Rose George, but far more importantly, she’s the reason we want to be better in everything we do.

Courtesy Elizabeth Krist

Elizabeth Krist, former photography editor at National Geographic

Dear Alice,

Do you remember?

My first story at Fortune, when you had me send Gilles Peress to Oklahoma to photograph a piece of farm equipment called the Ditch Witch?

When I brought you my recently cut hair to Garrison as ammunition for your endless battles with the deer?

Asking me to read aloud your letter mourning our friend Ethan Hoffman at his memorial in New York, when you were living in Paris?

That I kept a photocopy of one of your published poems on the back of my office door for a year?

Our trip to Greece, when we were at the beach, and you and Gary desperately tried to distract Anna, who was seven, from turning around and seeing a fisherman killing an octopus behind her?

Cooking for me when I stayed with you at 1 Fifth that week I was supposed to be taking care of you after your surgery?

How excited I was to meet Jim, finally, when he came back into your life?

Do you remember?

© Chris Killip Photography Trust

Duane Michals, photographer

In her sweet little Alice blue gown, the belle of Mississippi floated into town.

Alice was a poet, the real thing, which meant she was vulnerable, felt deeply, and loved deeply. When I look at the blue sky, I think of Alice.