Photographer unknown, Lily Wiley Vallejo and Louisa Vallejo with Emily Melvin, ca. 1870s

Collection of Ken Gonzales-Day

The history of Latinx people in photography is sordid. Often, we are the subject of suspect representation: grotesque stereotypes and racialized images that pathologize Latinx bodies as hypersexualized, criminalized, diseased, derelict, or dead. For the most part, the camera hasn’t been good to us. As photographic technologies developed from the mid-nineteenth into the twentieth century, so too did the ease with which depictions of Latinx people could be produced in photography and film, and imprinted on the cultural imagination. To this very day, we still encounter Latinx stereotypes that first appeared in early forms of photography

A nuanced account of Latinx photography is also difficult to discover. It takes searching family holdings, scouring library collections, and chasing fugitive archives to bring Latinx people into the story of photography in a way that captures the complexities of our lives without recirculating distorted and harmful images.

Ken Gonzales-Day, the Los Angeles–based visual artist best known for his Erased Lynching photographic series (2002–ongoing) and the related 2006 book, Lynching in the West: 1850–1935, has been researching and collecting Latinx photography spanning from the 1850s to the 1950s. That one-hundred-year period, during which the technologies of photography developed rapidly, was a crucial, disorienting century for Mexican Americans in California, many of whom had to learn to live in the United States as tenuous citizens under the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

This was an era of dispossession, displacement, and diaspora for Mexican America and also a century marked by violence, deportation, and large-scale erasure that sought to disappear Latinx people from history. It’s an era when Latinx people were “always on the edge of erasure,” as Gonzales-Day puts it, though the photographic archive he’s collected promises to keep us from oblivion.

Collection of Ken Gonzales-Day

Jesse Alemán: Tell us about the archives and collections you researched to find early Latinx images.

Ken Gonzales-Day: When I was invited to put together a group of images for this issue, I went through my personal archive, which is not really an archive. It’s a bunch of boxes I have in my garage and in my closet, and pictures on my computer compiled while I was working on my own research. It’s a very impromptu collection. I’ve written a bit on the history of lynching in the West, but I actually started out wanting to do a history of Latinx portraiture in California from 1850 to 1900. As someone native to California, I was interested in early California families whose traces can still be found around Los Angeles in street names and other locations. I wanted to learn more about my city, and California in general, so I spent a year researching. A number of the images that I’ve collected came from local archives and university libraries, such as the Bancroft at University of California, Berkeley, the Seaver Center for Western History Research at the Natural History Museum, and the Los Angeles Public Library, but some images come from my research on the history of lynching in the West. I’ve also collected some from my own family history to have a range of images and historical periods represented.

Courtesy the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History Foundation

Alemán: Your initial research was focused on 1850 to 1900, but you’ve broadened it to span 1850 to 1950. Looking at Latinx images over that century, what strikes you about the photographic record you’ve seen? What are the images, trends, or themes in Latinx portraiture?

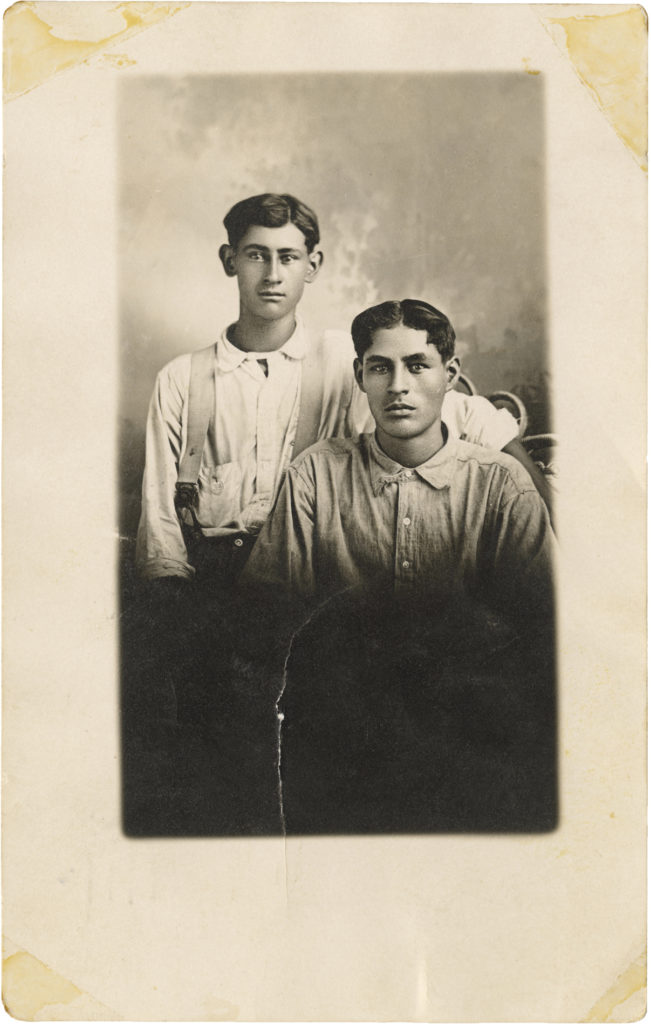

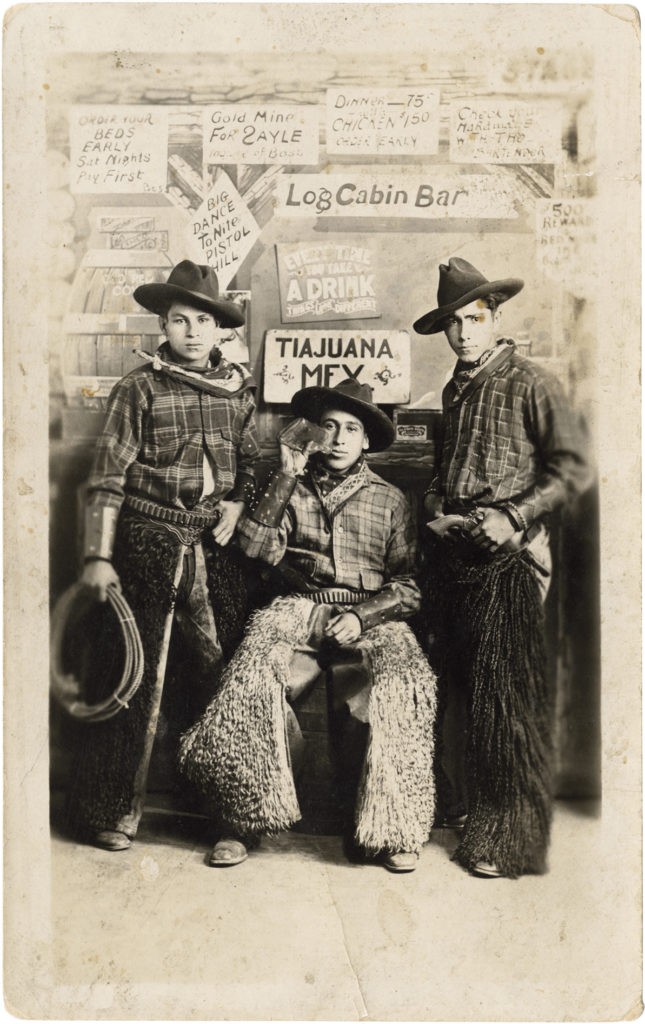

Gonzales-Day: I’m a professor of art and I teach photography. I have looked at a lot of art history books on the history of photography, and one of the things that struck me in the teaching of the history of photography in the United States—and globally—is that there are almost no Latinx people included. When thinking about what we think of as Chicano, Mexican American, Latinx here in the United States, there are just so few images. So, that’s how I started. I thought, Well, there must be portraits that were taken. There must be people who had the resources to document themselves, and they must have valued these pictures. As we all know and are familiar with in our own families, there is always a picture of the grandparents or some other old photograph of someone somewhere in the house. I very quickly found the traditional studio portraiture, but there were also a lot of commercial images, meaning those done for sideshows, theatrical performances, businesses, or calling cards. There were themes of the Wild West, California as the land of opportunity, or manifest destiny and U.S. expansion. You see images of Native Americans, crumbling missions, and the idea of the “decline” of people of Spanish blood, known as Californios, which, of course, was a racist trope that was very popular and still is in some circles.

Alemán: Given the span of your research focus, how have the changes in image technologies impacted, transformed, or influenced Latinx representation? How do these different technologies circulate or recirculate racialization of Latinx people?

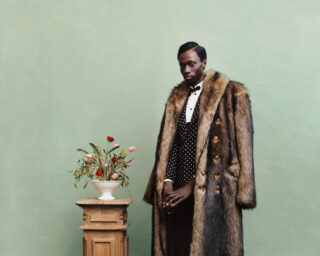

Gonzales-Day: That’s a complicated question. One of the things we certainly see is the idea of the “type.” In the history of racial formation, this idea was a way of grouping people that lead to racial categories. In the case of Latinx people, we have a very complicated history within the United States’ racial categories, and in California, in particular, we find two threads that move through early photography. The first is the Californio, lighter-skinned landowners asserting their middle-class standing through formal studio photography, through their clothing, and all of the trappings of Western, European-style portraiture. The second is the Indigenous, the mixed race, and the outlaw, known as the bandido. These two themes reappear throughout photographic images, in scenes of the wealthy at leisure, having picnics, days in the outdoors, and wearing lovely outfits versus images of the less prosperous at labor, in a field, or in front of a crumbling mission or collapsing building, often with some kind of tool in hand. These are the images of cultural difference within Latinx people.

Alemán: Definitely—the studio portraits shore up the class standing that some Latinx families enjoyed, especially in California, and particularly in Los Angeles, where there was a demonstrable elite Latinx middle class throughout the nineteenth century. This raises the question of access: Who has access to photographic studio portraits? And what’s the difference between studio portraits and other images you’ve encountered that are not produced in the studio?

Gonzales-Day: It varies by time because the technologies vary by time, but, certainly, by the 1870s and 1880s, the camera is lighter and easier to move, and so we begin to see some of these outdoor images—impromptu shots at picnics or large family outings—that are made possible by a photographer with relatively quick, light-sensitive material. Charles Lummis, for example, who in 1884 began walking across the United States and ended up in California, came to admire Spanish Mexican Californios. In the late nineteenth century, Lummis often traveled with his camera and made many cyanotypes. He could have an exposure and a print on the same day. His images represent the front edge of highly portable photographic technology for that period. Studio photographers, who made their living doing formal portraits, were also able to go out and photograph banquets, events, and sideshows, and then make pictures to sell to tourists. Postcards, view cards, and cartes de visite also become more prevalent at the time. So, there’s a wide range of uses for the photograph by the end of the century.

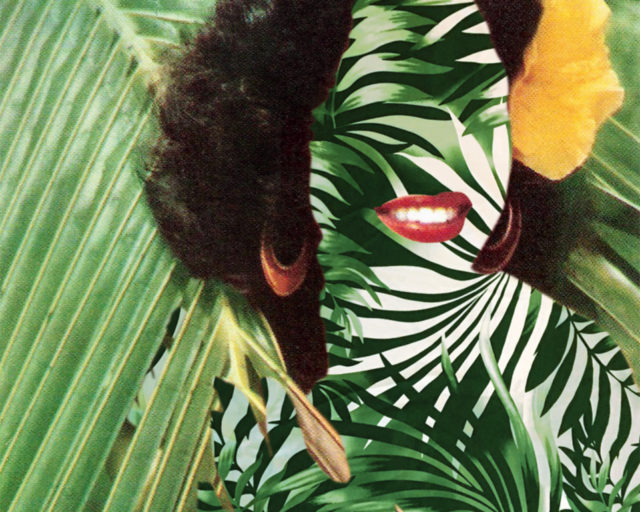

Courtesy the artist and Luis de Jesus Los Angeles

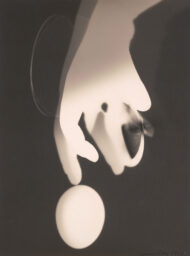

Alemán: On that last point, can you talk about your own use of the photograph for the Erased Lynching project? You photographed pictures or postcards of lynching scenes and then digitally removed the lynched body, foregrounding instead the faces of white violence. Explain that process and then, perhaps, situate your own photographic art in the trajectory of Latinx photographic technologies you just described?

Gonzales-Day: The Erased Lynching Series, which began around 2002, came about as a result of increased vigilante violence on the U.S.–Mexico border. We see basically a groundswell of anti-immigration rhetoric happening at the turn of this century. I just found myself startled by news of people crossing the border being shot by landowners, and there was this general sentiment that it was okay to shoot migrant people. As someone whose family has been here for several hundred years, I found myself thinking that it seems so wrong, and that it’s still ongoing, and the anti-immigrant rhetoric is still being used. So, with that in mind, I wanted to look at the history of racialized violence against Latinx bodies in California and the West, which is something I felt had been overlooked. The “erasure” was meant to say that Latinx bodies had been erased from our national history and, really, are still to this day not included. We are all familiar with the history of lynching in the United States, which is a history of racial terror against African Americans. Black Lives Matter, the George Floyd protests, and other current events have raised our awareness around the power of representing racialized bodies. This raises larger questions for me: Why are Latinx bodies still seen as different from other bodies? Why is their incarceration or death not registered in the same way that it’s registered with other bodies? As a Mexican American, I’m deeply troubled by this.

The arc of Latinx representation asks us to consider how we go from invisible, to visible, to invisible again. We’re always on the edge of erasure.

So, as a visual artist, my job is to try to create an object that reflects my feelings in the world. A poet looks at the world, has experiences, and then writes a poem. The artist’s job is the same: we experience the world, just as anyone else does, and then we produce something that will hopefully invite further investigation. That something is called an artwork. The Erased Lynching Series began as a way to invite people to think about the social dynamics that made these histories possible, and the social dynamics that made these histories visible or invisible. It’s an idea. Art is an idea. For me, the removing of the body in different lynching scenes was to not revictimize those killed.

To get to the last part of your question: How does this all fit into the larger history of Latinx representation? What can we learn from our past, and how does it help us connect and understand what it means to be Latinx now? Well, the arc of Latinx representation asks us to consider how we go from invisible, to visible, to invisible again. We’re always on the edge of erasure.

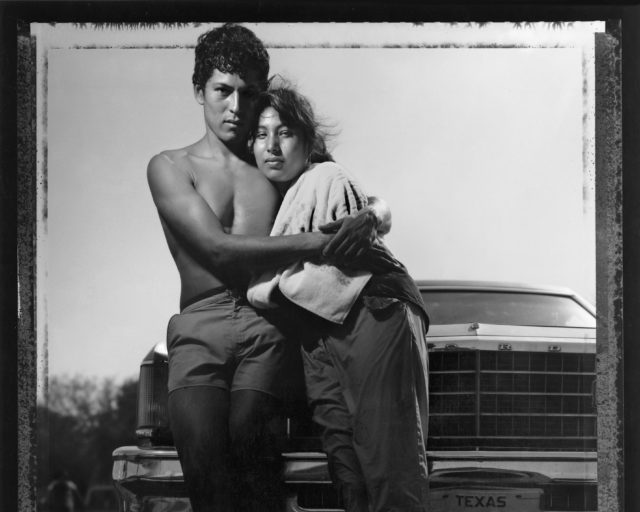

Collection of Darlene Bailey

Alemán: As a relatively new term, the x in Latinx marks the absence of something, but in doing so, the x also makes something present. Your project is doing something similar: it is bringing to the forefront what has been erased and simultaneously engaging erasure itself as an artistic act. So, let me ask you to reverse your creative process: Who, or what, would you add into your collection of Latinx images?

Gonzales-Day: In some of my other projects, I’ve worked on issues of the x. What is the x? It connects to gender roles, the question of gender formation, and also the overlap with Indigenous cultures. The x brings us to all of the different ways of being that many of us have, at least in part, in our ancestry. We need to add in the different gender and cultural expressions of the x. You think about the x as this slippery space where loss happens, but if you turn the x a little bit, it can become a plus (+). So, it’s a matter also of how the x multiplies or transforms the state that we’re in now to empower rather than reduce us.

Alemán: That’s a great point because the x doesn’t mark out something as much as mark that something is there. In this sense, what kind of record does the Latinx photographic archive capture?

Gonzales-Day: In all cases, the photograph is a way of marking, and particularly for us, looking back. Once the vernacular image comes out of the memory book and into the archive, then the language and meaning of that image change. So, one of the things Latinx people have to do is to collect and gather all of that information and history. There has been no place to collect our histories and no place to put them, and so many of them have been lost.

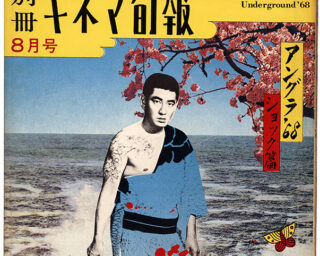

Collection of Ken Gonzales-Day

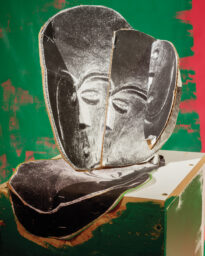

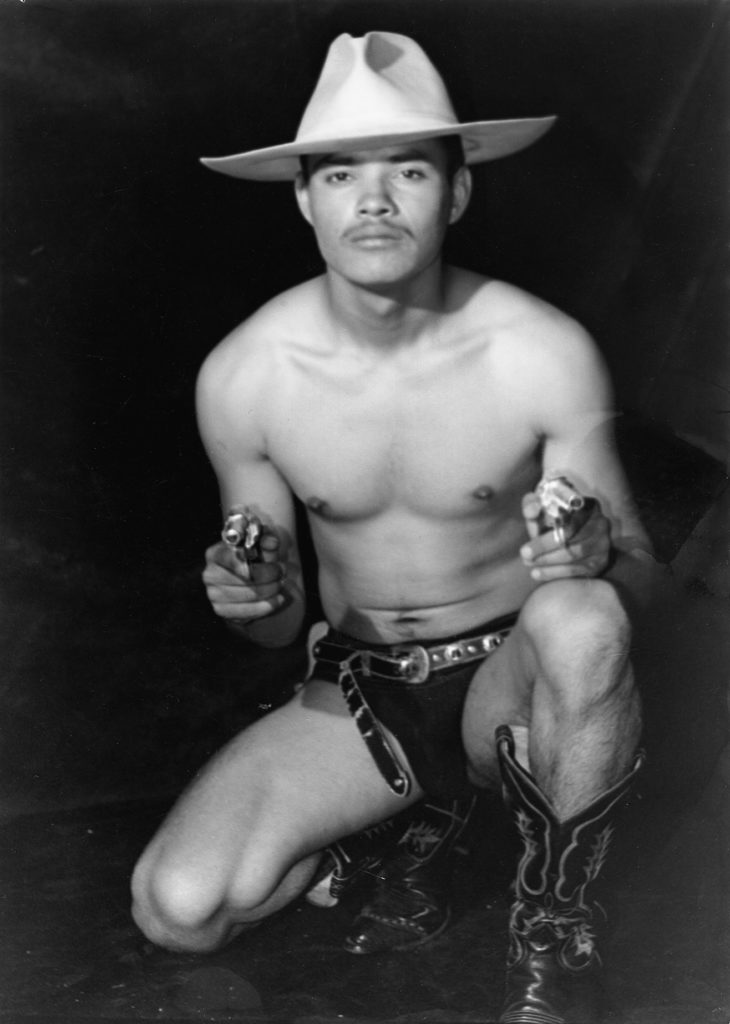

Alemán: One of the themes seen in your collection is that of the bandido—the Mexican bandit. Whether it be images of Joaquín Murieta, Tiburcio Vásquez, Pancho Villa, or nameless others, the bandido has been a mainstay over the one hundred years of photography you’ve collected. But one image in your archive stands out: it appears to be a Latinx man striking an outlaw pose with nothing much on except for a hat, cowboy boots, and black underwear six shooters out, so to speak. Tell us more about this image: Where does it fit in the longer history of the bandido figure?

Gonzales-Day: It looks like a 1940s or 1950s image, and, to me, it looks like what was very popular in the Los Angeles area: an early gay male culture of physical-fitness magazines that catered to men. Not necessary queer or gay, but they had that flavor to them, with young men flexing and changing from ninety-pound weaklings to musclemen. Some of it was about masculinity and not simply about sexuality, and some of it was about lifestyles where ideas of masculinity were performed. This image is very much in that style. It appears to have a fabric background, so it’s probably a studio shot, and it’s very much a beefcake model. He’s just got the cowboy boots on, a western-style belt, and then his guns out. It’s not even very well focused, but it seems to me like it’s both selling an idea of masculinity and fitness, along with an idea of the sexy bandit. He’s reinhabiting that bandit mythology, which we find in many parts of popular culture as well as in Latinx culture, too, where we might have to macho up or have to perform different elements of masculinity. This image, in particular, is a great example in the sense that we don’t see many brown bodies in that photographic history. Historically, the photograph of the bandit is taken once he is captured and in custody: he’s being held by police, and the photograph would be sold up to the day of his public execution. The trope of the criminal continued under President Trump, who used it to help secure his election and to further divide our nation. But in this particular image, we find it being used differently: Is it ambivalent? Is it simply that the guy needs a paycheck? Is he a victim? Is he empowered? I don’t know these answers, but this image definitely fits within the complex history of portraying the bandido.

Courtesy the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley

Alemán: Finally, what do these images tell us as artifacts of Latinx history as opposed to just illustrations of it? What sets the Latinx archive apart from, say, the photographic histories of Anglo America, or of Indigenous, Asian, or Black people in the United States?

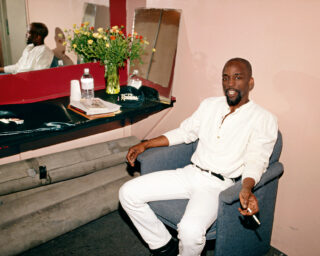

Gonzales-Day: First, I should say that there are shared elements of the camera for all of us. There’s a performative component for all photography that cuts across cultures and people because it’s used as a way to mark an event: a birthday or a wedding, for example. Since its origins, photography was a special thing, something done on purpose, and I think that’s universal. You can certainly see universal themes come through in Latinx photographs that are marking specific moments. Then, there are others that capture a Latinx cultural performance clothing, ranges of class difference, complexion, style, images of the dandy. There are so many things to find in the Latinx photographic archive that are part of a performative notion of culture. What is it to be Latinx? How much of it has to be recognized by others? Much of our identities require community, acknowledgment, consensus. The importance of the past, the importance of ancestors, the question of our connection to an “other” are tied to the idea of our being diasporic. Are we displaced? Are we where we should be? Are we a new identity? I believe Latinx people are very much part of U.S. history, yet we continue to be underrepresented at every level.

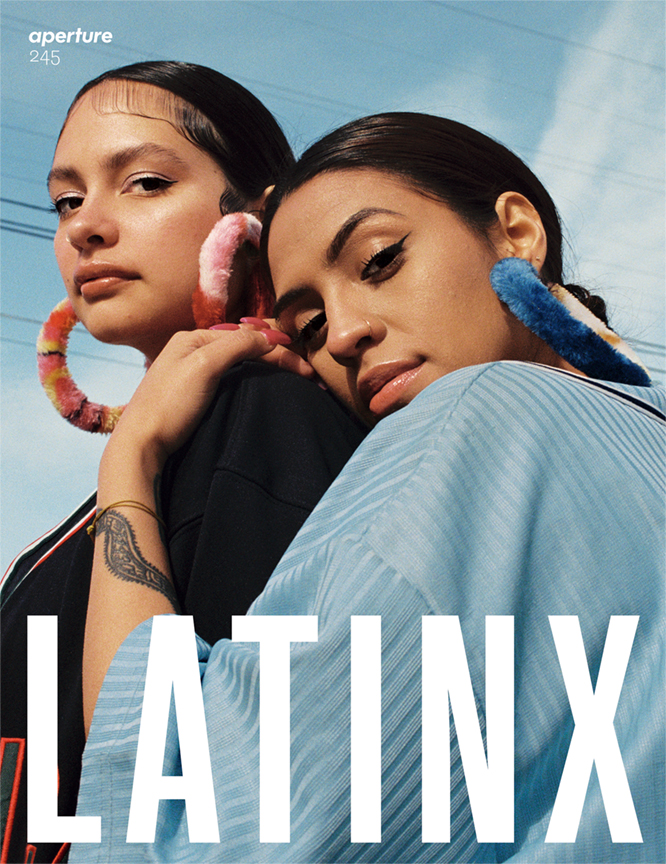

This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 245, “Latinx,” under the title “Always in Resistance.”