How Can Photography Shape our Relationship to the Environment?

An exhibition in Pittsburgh highlights the ways images can reveal the long-forgotten and unseen histories of ecology.

Xaviera Simmons, Sundown (Number Two), 2018

Courtesy the artist and David Castillo Gallery, Miami

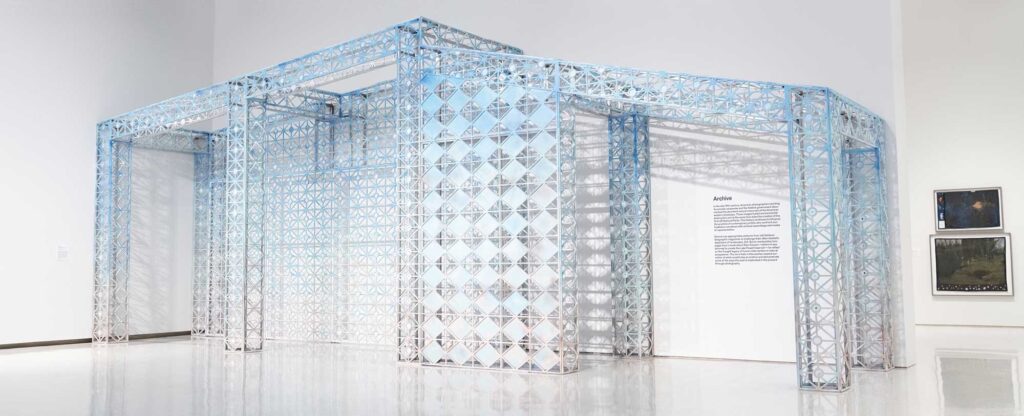

Edra Soto’s El Destino (Destination) (2024)—a wall-sized structure installed in the Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh—is filled with snapshots of San Juan, Puerto Rico: bright bougainvillea, neighborhood street views, a house glimpsed through a hole in a fence. Except, you wouldn’t know it. The images can only be accessed by bending down to peer through the little holes in the structure, as you would look through the viewfinders or keyholes of a different time. It’s a piece that sets the tone for Widening the Lens: Photography, Ecology, and the Contemporary Landscape, an exhibition that proposes expansive and multidimensional responses to human-environmental relationships as mediated through photography. The nineteen artists in the exhibition engage with land and place through the sensorial and the political, proposing possible answers to scholar Eva Díaz’s question, “How can we overturn the historical bias of experiencing site primarily through vision?”

Photographs by Zachary Riggleman

Near El Destino, David Hartt’s The Histories (Crépuscule) (2021) presents a fabricated experience of the sublime. A broad, woven vista of the Jamaican coastline recalls nineteenth-century paintings, while a blue-hued video of icebergs conjures a sense of impending doom. Graphically rendered palm trees on the far side of the tapestry situate the viewer in the tropics. All is set to lo-fi electronic music. The effect of peering at Soto’s small pictures fosters curiosity at the same time that it negates and obfuscates the type of broad views that Hartt’s work references and re-presents, offering two alternatives to, and critiques of, the visual language of colonial landscapes that has long characterized views of Latin America and other Global South territories. In contrast to Hartt’s monumental images, only one person at a time can see a particular view in Soto’s structure; landscape is construed as a slow, private experience.

Courtesy the artist

Widening the Lens succeeds in foregrounding realms beyond the visual and in centering artists who address fraught histories of slavery and forced labor, indigenous dispossession, and ongoing structural inequity and exclusion inscribed in landscape. They contend directly with the imperial origins of photography, as per theorist Ariella Azoulay. Through performative gestures, Xaviera Simmons, Dionne Lee, and Chanell Stone present various photographic approaches for grappling with the history of landscape in relation to the Black female body. In her Sundown series (2018–23), Simmons appears in brightly patterned clothing, holding up objects that refer to the history of Sundown towns, municipalities or neighborhoods that excluded Black people after sunset, a widespread form of Jim Crow–era discrimination. In Sundown (Number Two) (2018), the artist wears a purple patterned dress and stands with her back to the camera, facing a dense, green hedge. She holds across her back a photograph of a group of Black agriculture laborers and white overseers, all leaning against the back of a truck. These are sharecroppers, not enslaved workers, but the photograph still makes explicit a racial hierarchy that descends from chattel slavery.

The connection between Black bodies and the land is also front and center in Dionne Lee’s poetic photographs, which reflect on strategies and skills for wilderness survival and on the construction of the outdoors as intended for white leisure. Lee’s images of tender gestures also reflect on the medium-specificity of photography: Breaking the Fall (2016) closely frames the artist’s brown hands as they move across a color photograph of natural vegetation, tearing into it, as if making room for darkness and absent histories.

Courtesy the artist and Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York

Courtesy the artist

Stone’s dark, large self-portraits in agricultural fields allude to the perils of the outdoors that Black individuals and Maroon communities faced; other pictures focus on the place of Black bodies in urban, public spaces. With their somber, silvery hues, Stone’s photographs recall the deep darkness of Dawoud Bey’s and Roy DeCarava’s photographs, but frame an emphatically female gaze and presence in the landscape. The outdoors as a place for women and queer individuals is also foregrounded in Justine Kurland’s joyous Girls series (1997–2002), and in more somber, striking tones in Mark Armijo’s McKnight’s high-contrast, black-and-white series Hunger for the Absolute, which depicts queer male bodies languorously embedded within the Southern California desert. Sam Contis’s delicate black-and-white views of walls and fences in the British countryside, from the series Overpass (2020–22), home in on the modifications that render them porous and traversable, while veteran landscape photographer Victoria Sambunaris’s expansive views of sand dunes reveal the dirt bikers in their midst only to those who step up close.

Courtesy the artist and Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York

Courtesy the artist

The experience of the works in the second gallery is mediated by the mournful songs in Diné artist Raven Chacon’s Three Songs (2021), an affecting video of three indigenous women singing at historic massacre or displacement sites, accompanied by the rhythmic beating of a drum. Their voices activate Ho-Chunk artist Sky Hopinka’s delicate photographs of waters, skies, and forests, to which he applies delicate, meandering cursive writing. His phrases appear like lichen growing on the captured forms, making no distinction between human and non-human organisms. They reflect lyrically on long histories of togetherness, rather than separation between people and land, as do David O. Alekhuogie’s vivid and layered color photographs, with their attention to place, to food traditions, and Black history in works such as the collage Borrowed Recipe 1 (2021).

Nearby, Fever field (California poppies, hands, seabirds, sun), 2021 (2023), a wall-sized ethereal installation by Melissa Catanese, invites a multisensorial experience of beauty commingled with grief. The work features soft-focus color photographs of bright orange poppies in bloom alongside black-and-white fragments of found photographs. Printed on vellum, the pictures sway with the gentle air currents in the gallery. Approaching multidimensionality from a different angle, Erin Jane Nelson’s compellingly strange ceramics and a quiltlike fabric works, which contain embedded photographs of plant life, point at the sculptural possibilities of engaging photography with other physical media. They do not so much straddle as triumphantly override the tired dichotomy between craft and art.

Courtesy the artist

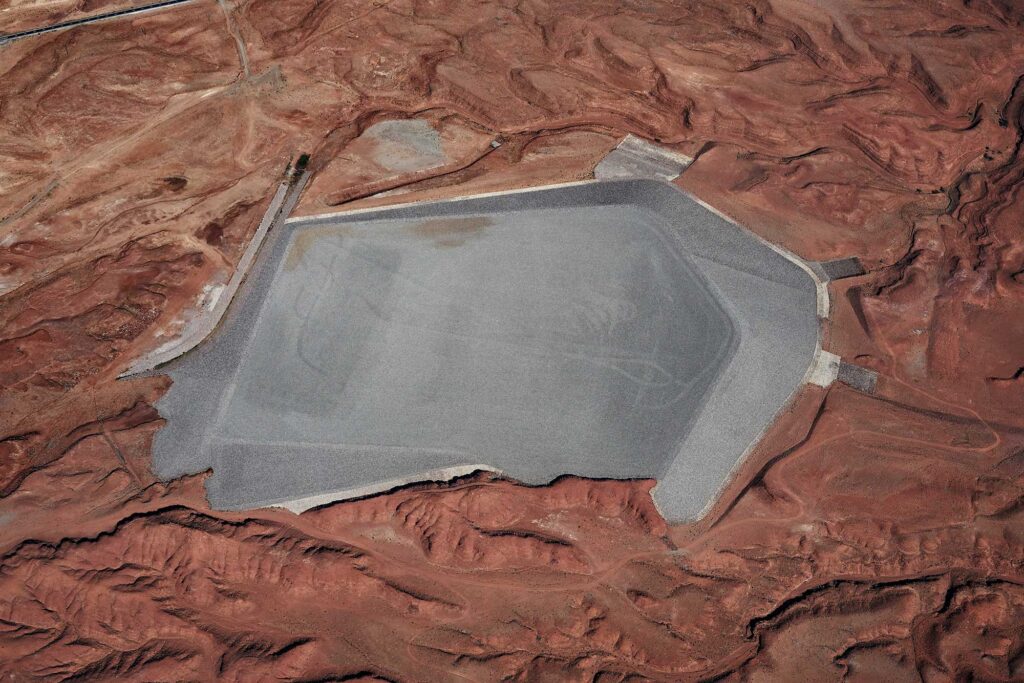

Ecological devastation and the uncertain future of sustainable human life on the planet are especially in focus in the last two galleries. Cyprien Gaillard’s video Ocean II Ocean (2019) includes dreamy underwater footage that reveals the surprising afterlife of New York subway cars dumped into the ocean, and the turtles and fish that are now its passengers. Fazal Sheikh’s documentary and aerial photographs of radioactive waste sites in Navajo territory in Utah are a sobering reminder of newer forms of dispossession and climate despoliation, and the ways environmental racism ruinously affects the lives and health of indigenous communities. The timed explosions of Lucy Raven’s video installation Demolition of a Wall (Album 2) (2022) punctuate the experience of the second half of the exhibition with a sense of eerie discomfort that echoes through the sparser installation of the third and fourth rooms, with the latter also showcasing Raven’s mysterious shadowgrams, moving the experience of landscape in this exhibition into its most abstracted presentation.

Courtesy the artist

Widening the Lens is a fitting title for a curatorial project that presents an expansive way to conceive of landscapes and human-environmental relations, while also leaving the visitor with a lingering sense of disquiet. The opportunity to see an installation or multiple works by most artists in the show allows for deeper engagement with the pieces’ multiple meanings as well as the conversations between them. The show foregrounds multiplicity, echoing scholar W. J. T. Mitchell’s definition of landscape as a “physical and multisensory medium (earth, stone, vegetation, water, sky, sound and silence, light and darkness, etc.).” At the same time, it lends credence to T.J. Demos’s sobering reminder that “photography doesn’t just show the effects of the Anthropocene, it also helps produce it.”

Widening the Lens is on view at the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh through January 12, 2025.