Photograph of the cover of Life magazine, April 30, 1965

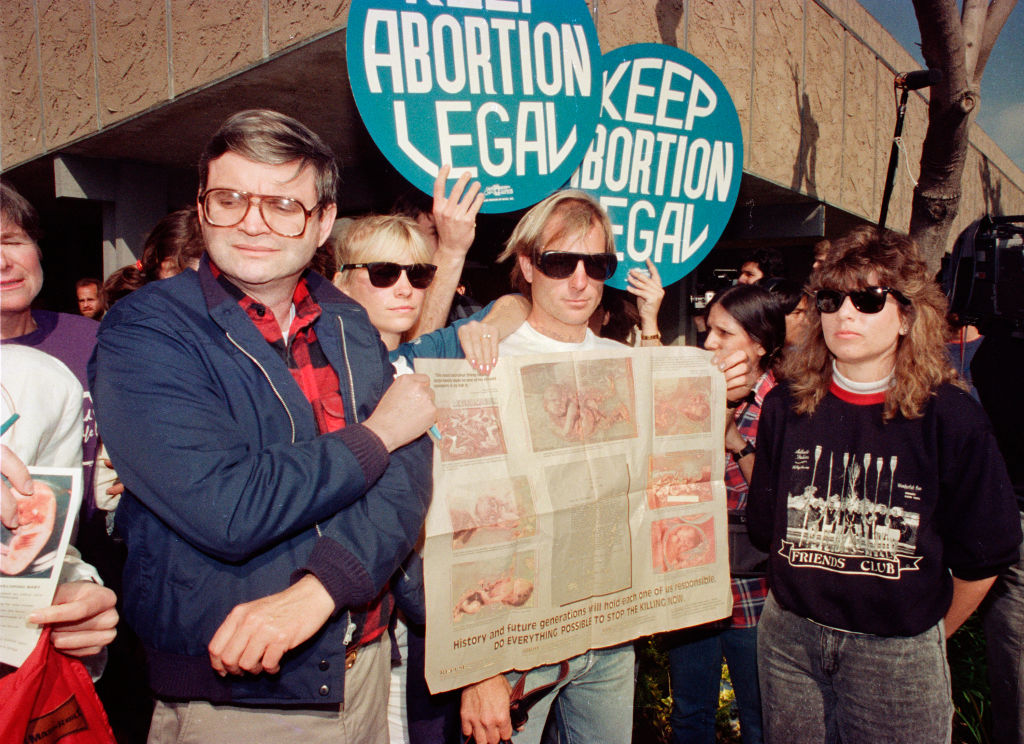

While I’ve been reflecting on the many farces and cruelties that led to the Supreme Court overturning Roe v. Wade, thus ending the right to safe abortion in the US, one particularly crass manipulation has been turning in my mind: the successful drive of some anti-abortion campaigners, over the decades leading to the ruling, to ensure that people seeking a termination be pushed to look at ultrasound images of the fetus before moving forward with their abortions. To be forced to look at anything is the stuff of nightmares, an almost cartoonish symbol of extreme control, a torture. By 2013, eight states had passed laws requiring providers to suggest a viewing of images from a mandated ultrasound (in three of these states, the law permits the woman to avert her eyes from the image, though the doctor must still display and describe the image). This was done on the justification of giving patients “information,” and off the back of research from the 1980s conducted with just two women, both of whom actually wanted to give birth, that suggested that seeing grainy photos of the fetus helped with bonding. The push for such requirements shows society’s steadfast belief in images to awaken, to chastise, to shame, to convince. The thrill for anti-abortion campaigners was the motif of baby, of tiny man: the bobbing head, the curved body. Could Roe have fallen without the proliferation of such visuals—the theater of fetuses—brandished outside clinics, in schools, and online?

As commentators rush to analyze the social, political, and religious shifts and divisions that led to the fall of Roe, the role of photography must also be acknowledged. That means photography in the widest sense, including medical imaging, which, in the context of anti-abortion campaigning, has been subjected to selective editing and visual distortions. See, for example, the infamous anti-abortion propaganda film The Silent Scream—released in 1984 and shown in numerous schools, churches, and at the Reagan White House—in which speed and sound, including doomful music, were used to effectively turn ultrasound recordings of the abortion of a twelve-week fetus into a sensationalized snuff film. The fetus (usually at that moment around the size of a lime and not sufficiently developed to feel pain) was enlarged so as to resemble a grown baby and depicted, via close-ups on key angles of its head and heavy use of slow motion, “screaming” in response to the surgical tools. The visual was intended to back up the narration, by the anti-abortion doctor Bernard Nathanson, that the fetus was “another human being indistinguishable from any of us” and thus acting in ways we would imagine ourselves when in pain: calling out, retreating, writhing.

Images are often taken as evidence of reality, and by default, personhood and existence—all the things anti-abortion advocates are keen to assert. The ability of photographs to supposedly prove, to make things true and lasting, can be a horror and a danger. There was perhaps never a more feverish attempt to harness that power than in the battle to fell Roe, in which the ultrasound has been proffered as an illusion of humanity. In the push for forced pre-abortion fetus-viewing (a drive partly inspired by the sensation caused by The Silent Scream), the hope of anti-abortionists was that women who came face-to-face with the image would be overcome, moved in some way, and change their minds. In fact, researchers have found that the process makes little impact on decisions to go ahead with the procedure. Other impacts of this charade—on women’s time, their patience, their mental health, their peace—are, of course, unknown.

As commentators rush to analyze the social, political, and religious shifts and divisions that led to the fall of Roe, the role of photography must also be acknowledged.

Writing recently on the fall of Roe in the London Review of Books the historian Marina Warner notes of early abortion battles, “it was not only a question of what language to use to express the arguments for women’s authority over their own bodies, but of visual representations too. The antagonists used images quite unscrupulously to spread their arguments about the foetus being a human person, with a soul, images which erased the personhood of the women themselves.” As she implies, the anti-abortion movement owes its success not only to the direct weaponization of images, but also equally to their capacity for misinterpretation, their dangerous veneer of neutrality that smothers questioning, and the impression of progress implicit in the association between photography and technological development.

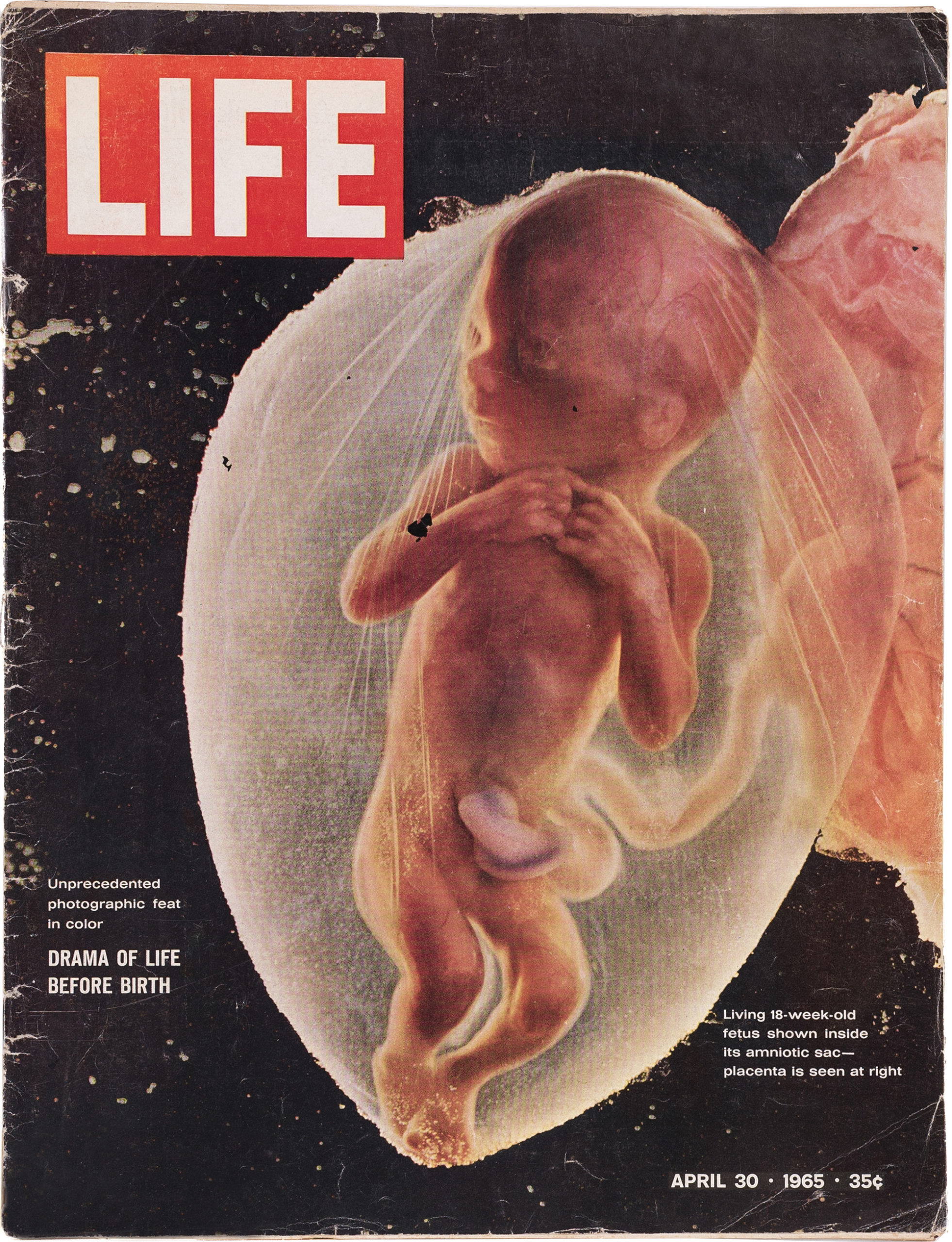

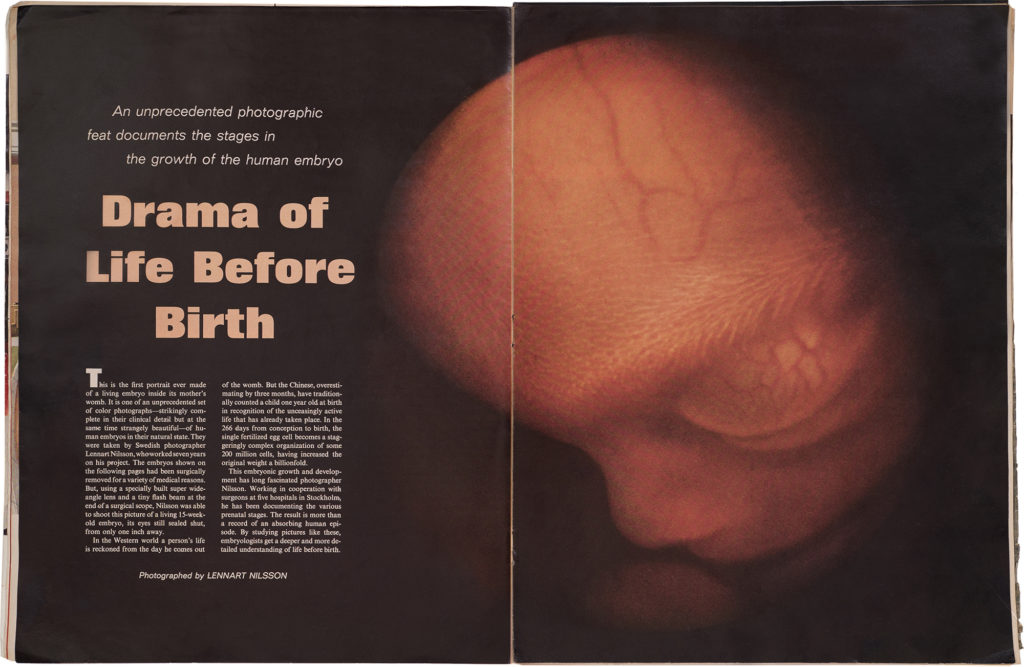

The thrust of the fetus into the public imagination can be traced to the Swedish photographer Lennart Nilsson and his book A Child is Born, first published in 1965 by Bonnier, as well as the corresponding Life magazine cover story “Drama of Life before Birth,” which appeared that same year to promote the book. (Interestingly, 1965 was also the year an obstetrician in Glasgow became the first to experiment with the use of ultrasound imagery for pregnancy.) The story featured color images of supposedly living fetuses at various stages of development—an “unprecedented photographic feat,” according to the magazine’s cover. Through Nilsson’s lens, which purported to offer a direct view inside the human body, the fetus was a tiny floating “spaceman,” a being destined for, and deserving of, the chance to continue its life on Earth—something emphasized equally by the magazine’s chosen headline. The images and their insinuations have, as the historian and gender-studies scholar Barbara Duden writes in her 1993 book Disembodying Women, “since become part of the mental universe of our time.”

Nilsson began making fetal images in 1952, when the Bonnier-owned magazine See commissioned him for a story on the anti-abortion Swedish gynecologist Per Wetterdal and his hospital’s collection of fetal specimens. Wetterdal had hoped that these specimens, if widely seen, could curb enthusiasm for abortion. This story ran with the headline, “Why Must the Foetus be Killed?”. Sensing an opportunity to capitalize on and contribute to moral panic, Bonnier funded Nilsson to continue the project and sent him to tour hospitals; over the subsequent decade it published various anti-abortion articles with his images. But come the mid-1960s, support for abortion in Sweden was growing, and some of these stories received backlash. Also conscious of a wider appetite for improved sex education and information on women’s health, Bonnier abandoned the debate and packaged Nilsson’s A Child Is Born as a pregnancy guide, with additional images guiding couples through conception, fetal development, and birth. It contained no reference to abortion.

Nilsson’s photographs have since had a complex life. Some have, as the publishers supposedly intended, been used in maternity care and education. Others, over the book’s many reprints and international editions, have been proposed as works of art. In 2009, Bonnier repackaged A Child Is Born as a shiny coffee-table book, with commentary from the picture editor Mark Holborn, rather than the gynecologists and doctors of the early editions. The following year, the images went on display at Fotografiska in Stockholm. The breadth of contexts demonstrates how images of the fetus have, through agenda and interest, crossed genres and been liable to repurposing and reformatting. Perhaps the most notable role of Nilsson’s fetus “feat” has been in providing the anti-abortion movement with a readable symbol, a clear logo, and thus the aesthetic punch that is, arguably, essential to any successful protest movement. The images provided content for countless posters and fueled, in the battle over abortion rights, the replacement of medical knowledge with gut reaction and superficial impression.

Ironically—though fittingly, given the anti-abortion movement’s penchant for chicanery—almost all of Nilsson’s images were not, in fact, of babies steadily developing in the womb. Rather, they were of dead fetuses, the remnants of ectopic pregnancies or abortions, which Nilsson had posed in front of a backlight or in dishes of liquid to suggest their position inside the body and the illusion of a prosperous life. “It is presumed that the readers have realized that the pictures show foetuses that are dead,” the doctor Lars Engstrom wrote in 1965, in a critical review of the book in the journal Swedish Medical Associations. He referred to one especially florid caption for an image of a four-month-old fetus: “Infinite calm rests in these faces. They look as if they are waiting for eternity. But it is the short life on earth they are preparing for and it is not sleep that keeps their eyes shut.” Engstrom asked, “Is this embryological poetry or deception? The truth is down to earth and simple: the eyes in the picture will never see.”

Nilsson’s images pay little attention to the bodies that contained the fetuses—it is unlikely the women were even asked for permission before the remnants of their pregnancies were photographed. His work instead turns pregnancy into a story that could be told without or even despite of the pregnant person, or to them, by external observers. As Warner argues in the LRB, this is typical of images popular with the anti-abortion movement, in which the pregnant body is often not even a mere vessel but completely absent. “Treating a fetus as if it were outside a woman’s body, because it can be viewed, is a political act,” Rosalind Pollack Petchesky writes in her important essay “Fetal Images: The Power of Visual Culture in the Politics of Reproduction,” published in Feminist Studies in 1987. Indeed, such visuals helped assert the independence of the fetus, as a separate life and entity, a supposedly soulful being of its own. They helped conjure the utterly inappropriate “pro-life” tag that was, until recently, used widely by anti-abortion campaigners, and create the warped sense of equality between “lives” that allows the rights of the fetus to prevent a ten-year-old rape survivor from pursuing an abortion (as was recently the case in Ohio). The images helped make “real” something that for most people floated tenuously in ambiguities and personal philosophies about the very nature of life—the notion of when personhood begins, of when we become “human.” And, of course, the images are emblematic of the entire concept of photography, the core property of which is to slice, to frame one thing and not the other, to remove context and surroundings. What is out of frame does not matter.

Indeed, there is a bigger link, beyond the fetus, between the fall of Roe and photography. Consider the medium’s entire history as a device for enshrining men’s vision and hopes for the world (natural, given who has typically made and commissioned photography): men as active, driving, moving; women and children as accessories, caring, waiting, fragile. Photography has, for most of its existence, upheld regressive systems. It has been a crucial tool in the lie of the idealized family and the fantasy of serenity. Recall how camera companies, in marketing the technology to the masses, directed new patrons to record their kin and family milestones—weddings, graduations, first days of schools, and births, endless births, and the slippery, ideally pink, forms of babies—and paste them into albums. They directed not only what should be photographed but also what was aspirational, what was normal. In the fight to limit abortion, such motifs have been employed with zeal as a way of reassuring conservatives and disparaging would-be outliers. They appear, for example, in political-campaign videos and images, formats that, tellingly, swelled from the 1984 Reagan presidential campaign onward, and that ushered in a culture of appearances and facades that was crucial to the anti-abortion movement. Such visuals showed domineering fathers, round-cheeked children, and mute wives (the idealized mother). They served to protect an imagined history that was purported, without care for accuracy, to be abortion-free, to be good—better.

The lie of abortion as a “new” right—a supposed result of feminism or modernity or spiritual decline—underpins one of the more bizarre moments of interplay between photography and abortion: the strangely avant-garde films of American father-son duo Francis and Frank Schaeffer, which helped radicalize evangelicals, a group previously relatively neutral on abortion. (Though it is near impossible to imagine now, abortion was once accepted by many religious groups, many of whom viewed it as a Catholic issue or a personal matter between woman and doctor, as Jia Tolentino explores in a recent essay in The New Yorker.) The story starts, of course, with male ambition. In the 1960s and ’70s, the aspiring filmmaker Frank Schaeffer, a devotee of Fellini, Bergman, and Vittorio De Sica, was growing up in the Swiss Alps in the evangelical Christian commune L’Abri, led by his father, the theologian Francis Schaeffer. L’Abri hosted a steady stream of high-profile visitors, including Billy Zeoli, who was president of the large Christian film company Gospel Films and, in the mid 1970s, the unofficial “White House chaplain” to President Gerald R. Ford. Zeoli suggested that Schaeffer turn his attention to moving image, proposing, with the guarantee of a multimillion-dollar budget, a series of Christian documentaries. Through rampant nepotism the teenage Frank got to direct. “I was looking at it as film school,” he recently told the writer and podcaster Jon Ronson, noting that he hoped the work could be a springboard to Hollywood, where he could make “real movies.”

Midway through production, Frank had an epiphany, inspired partly by his experience as a teen father: the films should reference abortion, especially the recent Roe case. He convinced his father to target the issue, and the elder Schaeffer appears on camera, saying, “By this ruling, the unborn child is considered not to be a person.” The film series, titled How Should We Then Live?, was a hit with evangelicals. And yet the audience was not totally overcome or inspired by the abortion segments. Frank was undeterred; he recommended doing a new series just about abortion, and the elder Schaeffer agreed. He was keen, Frank told Ronson, to secure “another paycheck for his errant son.”

The new work, titled Whatever Happened to the Human Race?, was made with similar ambition and a comparable budget. Created in collaboration with C. Everett Koop (later, Surgeon General during the Reagan administration), the five-part documentary includes a scene of an anti-abortion doctor standing on a rock in the Dead Sea, surrounded by a thousand naked baby dolls—a mass of chubby, plastic limbs. Other dolls were filmed rolling down a conveyor belt into an incinerator. In another scene, a toddler is trapped in a cage, crying and rattling the bars. The work is strange and visually experimental, and was, at first, unpopular. Few evangelicals turned up to screenings, and few church leaders cared to give their voice to an issue they considered settled. But when the press picked up on the oddness of the cinematography in the context of the topic of abortion, protestors—including feminist groups—started to picket screenings, which caused Schaeffer fans to turn up in support. With each showing, the group’s size swelled until, eventually, abortion became an issue that reliably attracted evangelical protesters who were inspired by both the film’s rhetoric of baby-killing and the motivational aspect of a clear enemy.

Frank Schaeffer later left the evangelical movement, but he kept images from the films in his show reel and eventually made it to Hollywood. His films include Headhunter, an occult-themed horror film, and the post-apocalyptic Wired to Kill, which features a murderous robot. “[W]ith the abortion issue, the religious right found a catalyst that energized a political movement that then evolved into all sort of other areas, from trying to attack the gay rights movement to getting people to vote for Republican candidates,” Schaeffer told NPR in 2008, “the energy, the catalyst, all of that happened when my father and I went out with these film series and books and basically told Christians you need to apply Christian teaching to all of life.” He recalled the doll scene and how the “surrogates for aborted babies were just this kind of artistic image floating in a turquoise . . . space.” It would be a joke if it weren’t reality. The dreamt-up images of a teen Fellini fan reverberate to this day, shaping policy and ruining freedoms.

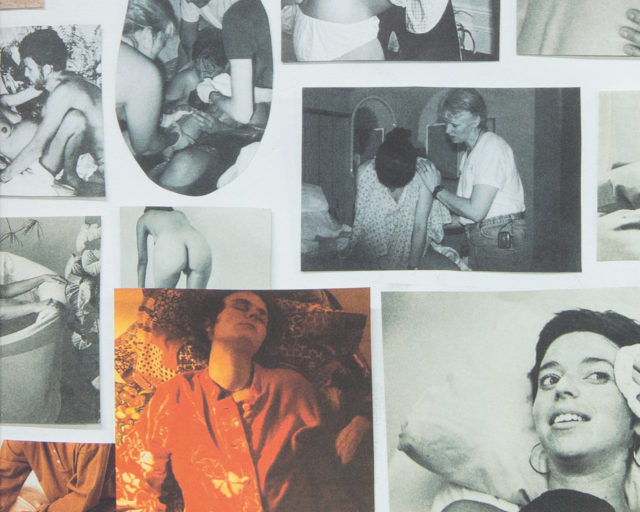

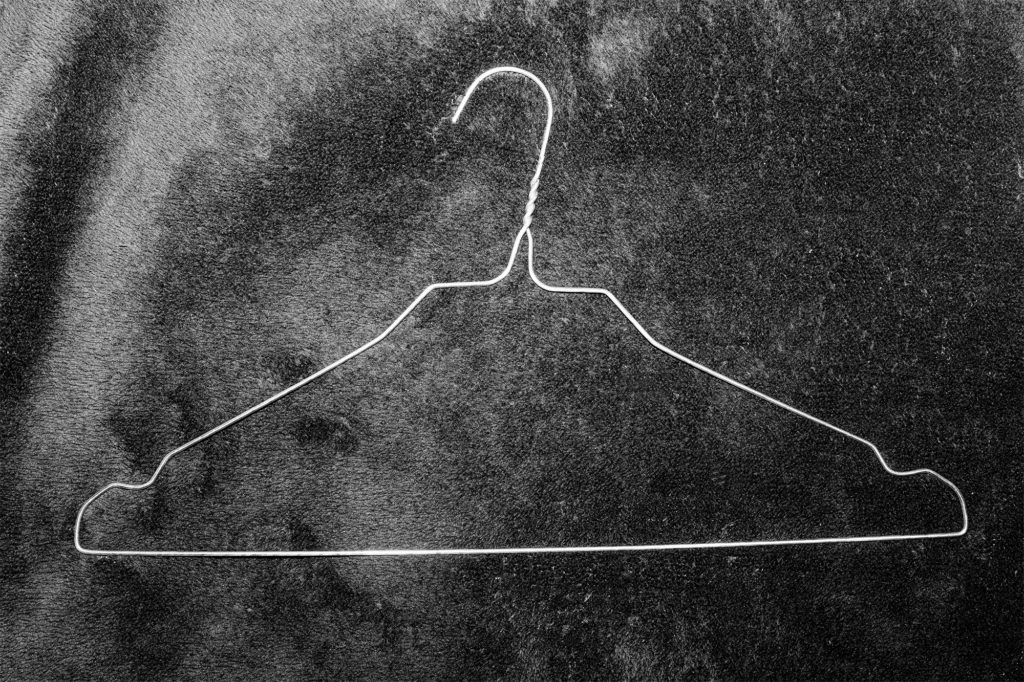

Today, the question Warner references—how should pro-abortion campaigners deal with visual representations when it comes to abortion?—remains unsettled, and it will be debated even more as activists unite post-Roe. A small number of photographers have, over the years, offered their own suggestions. In 1972, as part of her bold explorations into women’s limited choices, Abigail Heyman photographed herself having an abortion. The camera points down at her open legs and the light is stark; there is no warmth, no subtlety. More recently, Laia Abril’s exceptional book On Abortion (2018), from her long-term project A History of Misogyny, has been receiving the acclaim it deserves. Abril considers the history of abortion, the damage caused when women lack legal, safe, and free access, and the plight of the forty-seven thousand women, worldwide, who die each year due to botched procedures. The book amalgamates images, text, and ephemera to make its case with clarity and force. It takes on a topic with a thoroughness that exposes how frequently photographers have shied away from addressing it robustly, or from engaging with personal or shared experience.

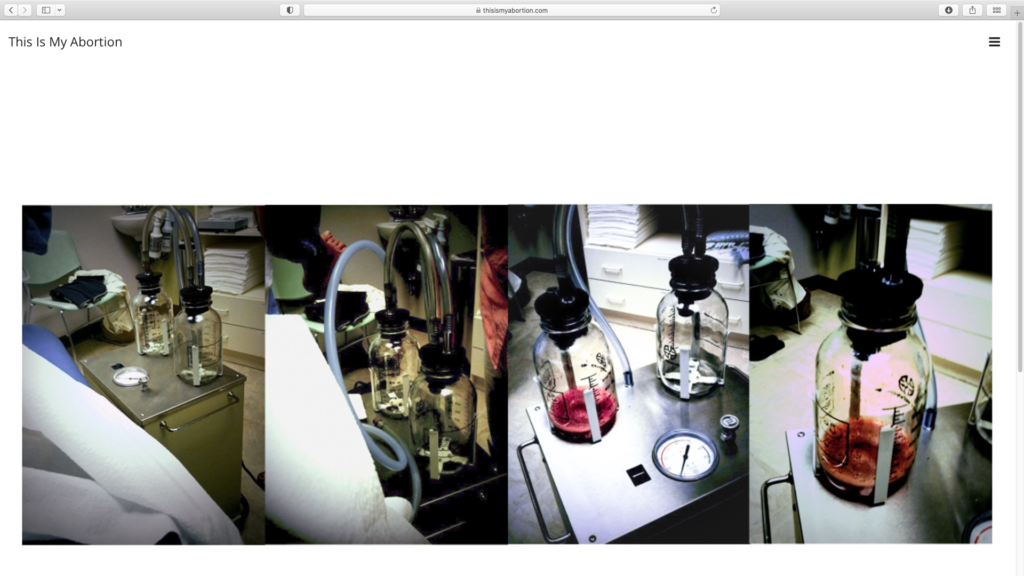

It has become popular to argue that the pro-abortion cause is, in general, unphotogenic. That there is nothing suitable or palatable to pull at heartstrings that isn’t gory or, by contrast, humdrum. Implicit in this idea is the shame that pervades abortion: the notion that to picture the ease of the process would only make the issue seem flippant, the advocate uncaring, or the patient untroubled (one could build a strong argument that this would be a good thing). A rare project that cuts through the expected histrionics is the committedly calm, and brilliantly useful website This Is My Abortion, where an anonymous woman posted photos she took on a concealed camera phone during her abortion. “My hope is this project will help dispel the fear, lies and hysteria around abortion,” she writes on the landing page. In an article for the Guardian, she recalls arriving at the clinic to see protestors: “Viewing, again, the horrific graphic images they displayed, I wasn’t sure if I was more afraid of being harmed by the anti-abortion protesters or if I was more anxious about the procedure itself.”

A sea of images—what good have they done? To take on Warner’s question, I would propose the answer to the “visual representation” of abortion is not to be found in more photographs. Nor is it to be found in the partisan or the contrivedly wrought. The solution, instead, could come from a push to question what a photograph can be, in the inclination to challenge the truths about images we have accepted in the past. It could also lie in resisting the spray of narratives and sentimental insinuations—of deaths, missed chances, regrets, or could-have-beens—the projections and delusions and imaginatory leaps that have defined the discourse of both photography and abortion. It could be there in the stoicism to confront the tendency to search for meaning or some supposedly lingering emotional truth. Nilsson’s “babies” were not miracles of life but abortions. There was no cry in The Silent Scream. The dolls in the sea were just dolls. The metaphors fall; the reason emerges. A cluster of cells is not a baby. The eyes in the picture will never see.