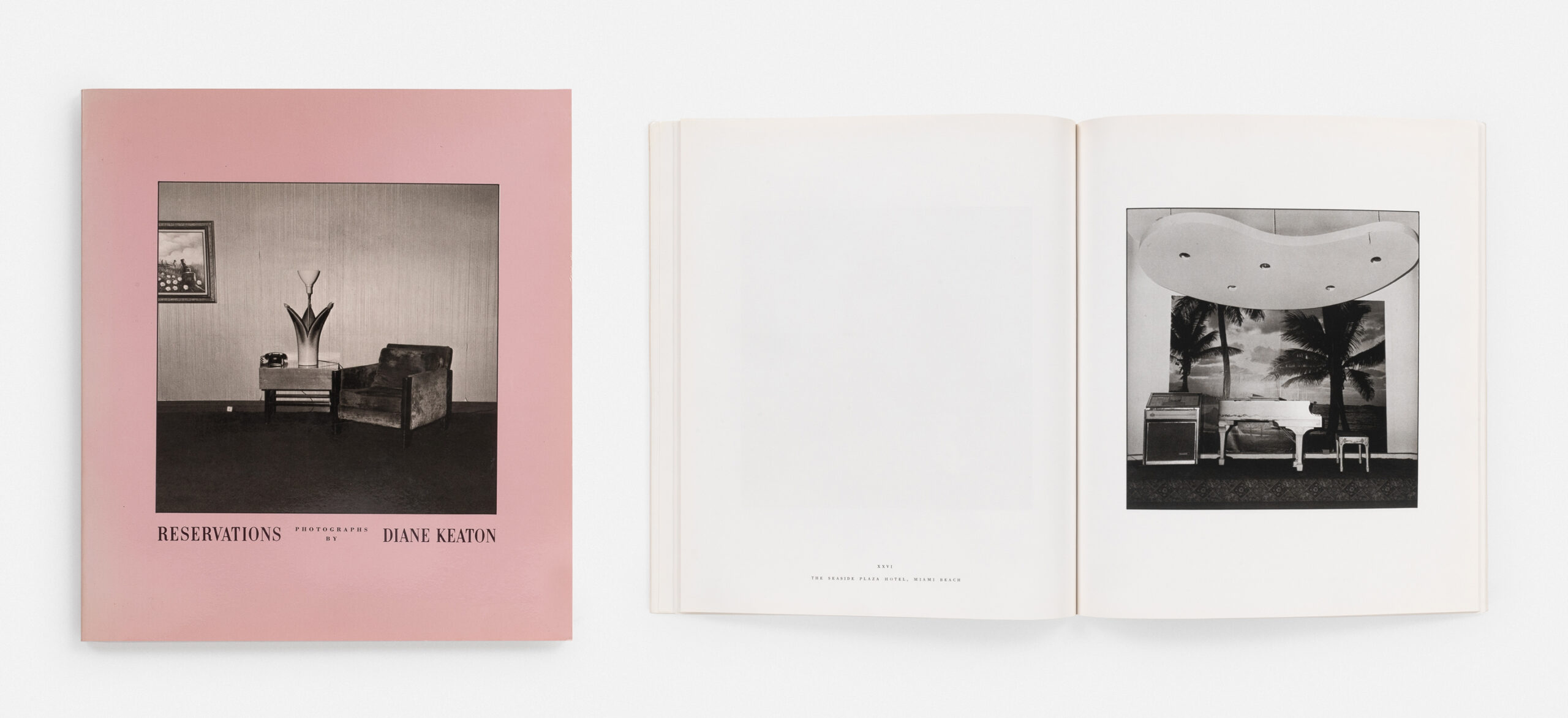

Diane Keaton, Reservations (Detail), 1980

Since Diane Keaton’s death last Saturday at age seventy-nine, much has been said about her great depths as an actor, one who brought to her best performances a vivacious vulnerability and flustered grace. She was other things too: an openhearted memoirist, a designer, an androgynous icon, a single mother. Less discussed is Keaton’s surprising contribution to photography, a medium she held close throughout her life.

A couple of years ago, a friend with unimpeachable taste gifted me Keaton’s first photobook, Reservations, published in 1980 by Knopf, and I’ve treasured it ever since. Like all great photobooks, it seems endowed with talismanic powers. Clad in a flamingo-pink cover, the monograph consists of forty-five black-and-white photographs of deserted lobbies and banquet halls in luxury hotels across the United States, taken during the 1970s—presumably as Keaton traveled around the country promoting New Hollywood classics like The Godfather, Annie Hall, Looking for Mr. Goodbar, and Reds, which had begun production in 1979.

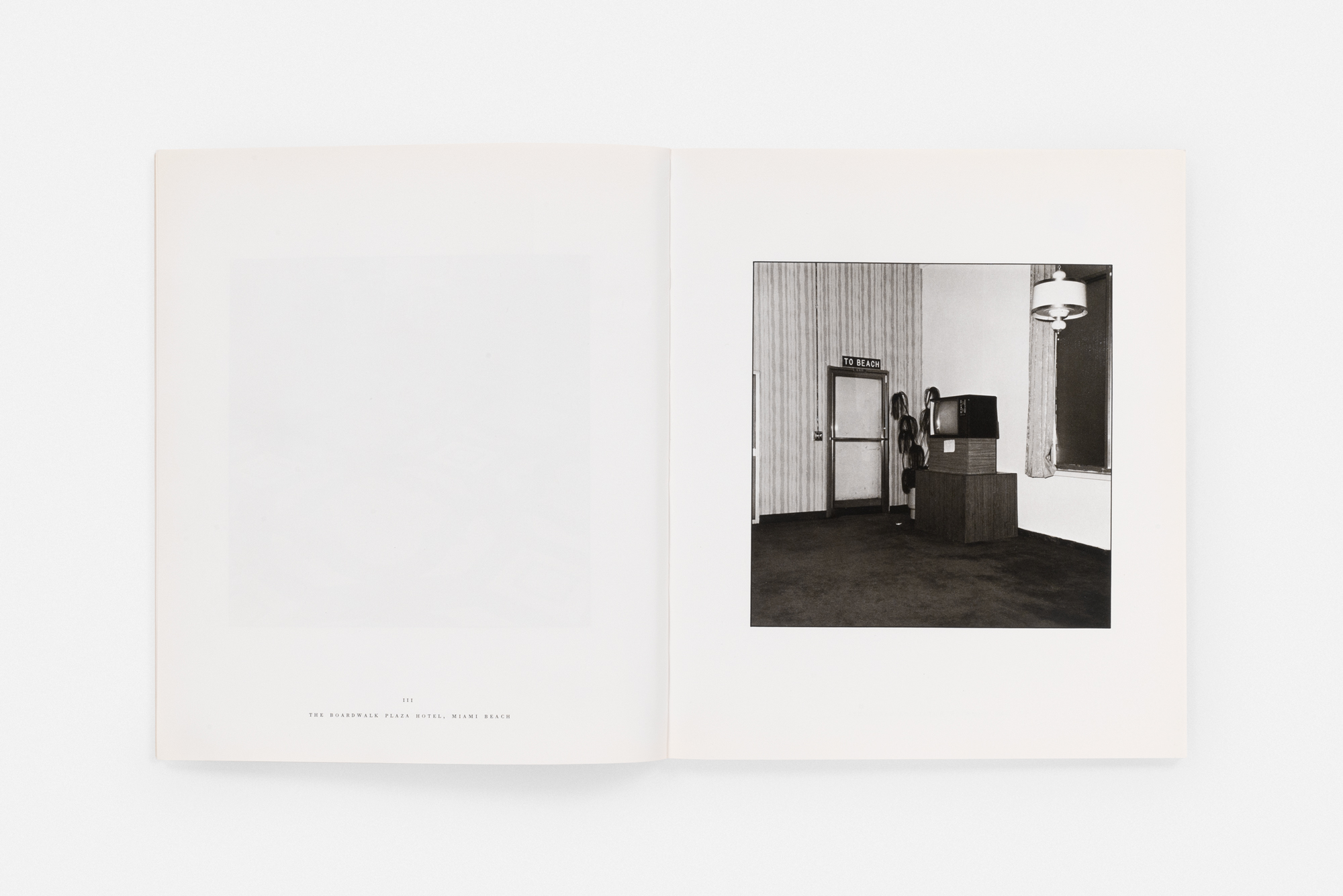

When trying to describe the nervy warmth of Keaton’s performances, people often resort to “lived-in,” that film-criticism cliché. Her photographs are seemingly the opposite: unpeopled, icily observed interiors that announce a “strong, direct photographer with a cool and deadly eye,” as the jacket copy puts it. The book makes no mention of her acting credits, and why should it? No mere vanity project, Reservations is an angular meditation on American emptiness, the kind Todd Hido would thematize to enormous success two decades later. Keaton locates a wry, forlorn comedy in awkward furniture, plastic plants, florid wallpaper, ersatz backdrops, quirky light fixtures, and conspicuous cables snaking down white walls, all shot deadpan (a word coined in the 1920s for that other Keaton, Buster) and gilded with a harsh flash that renders surfaces slightly unreal.

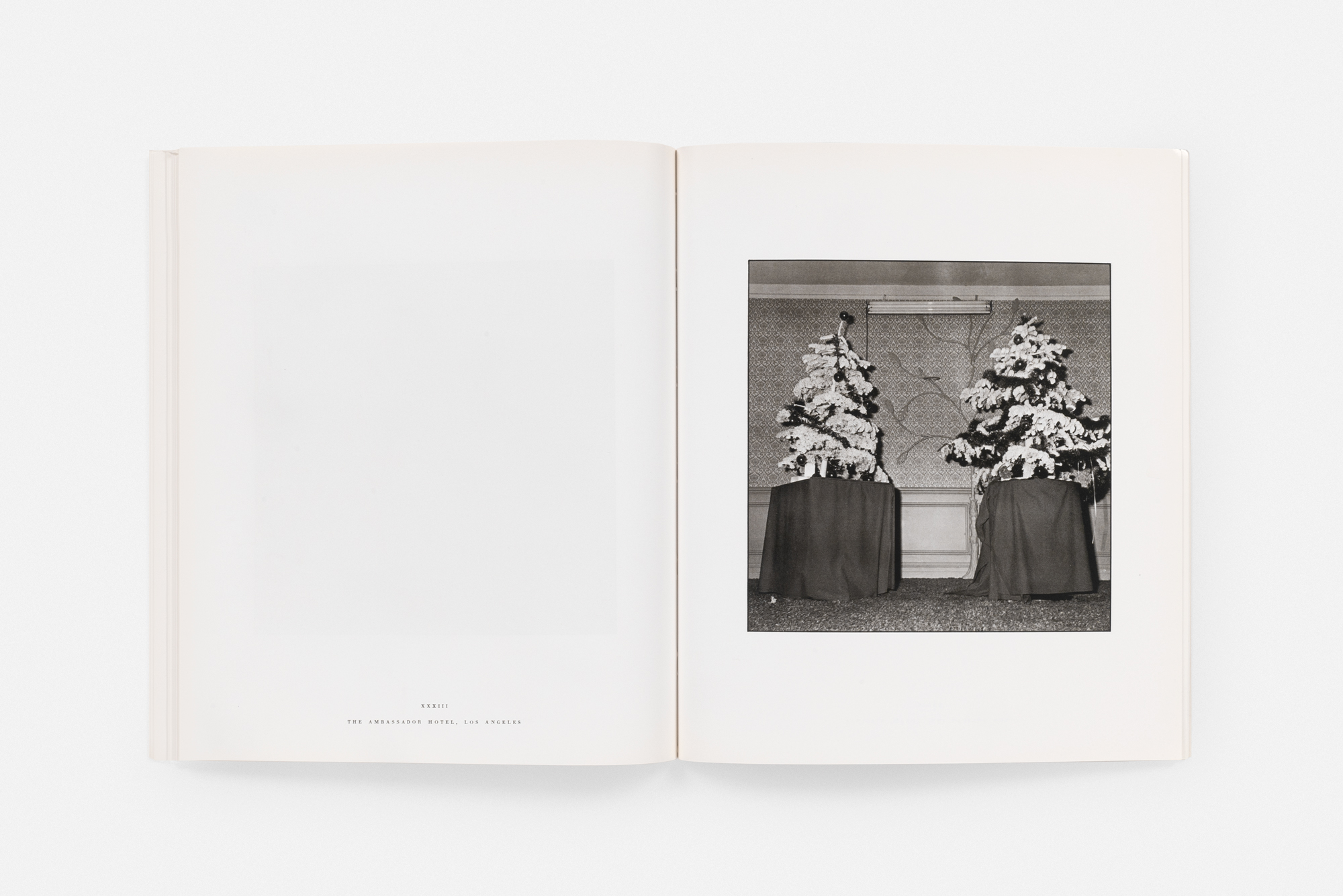

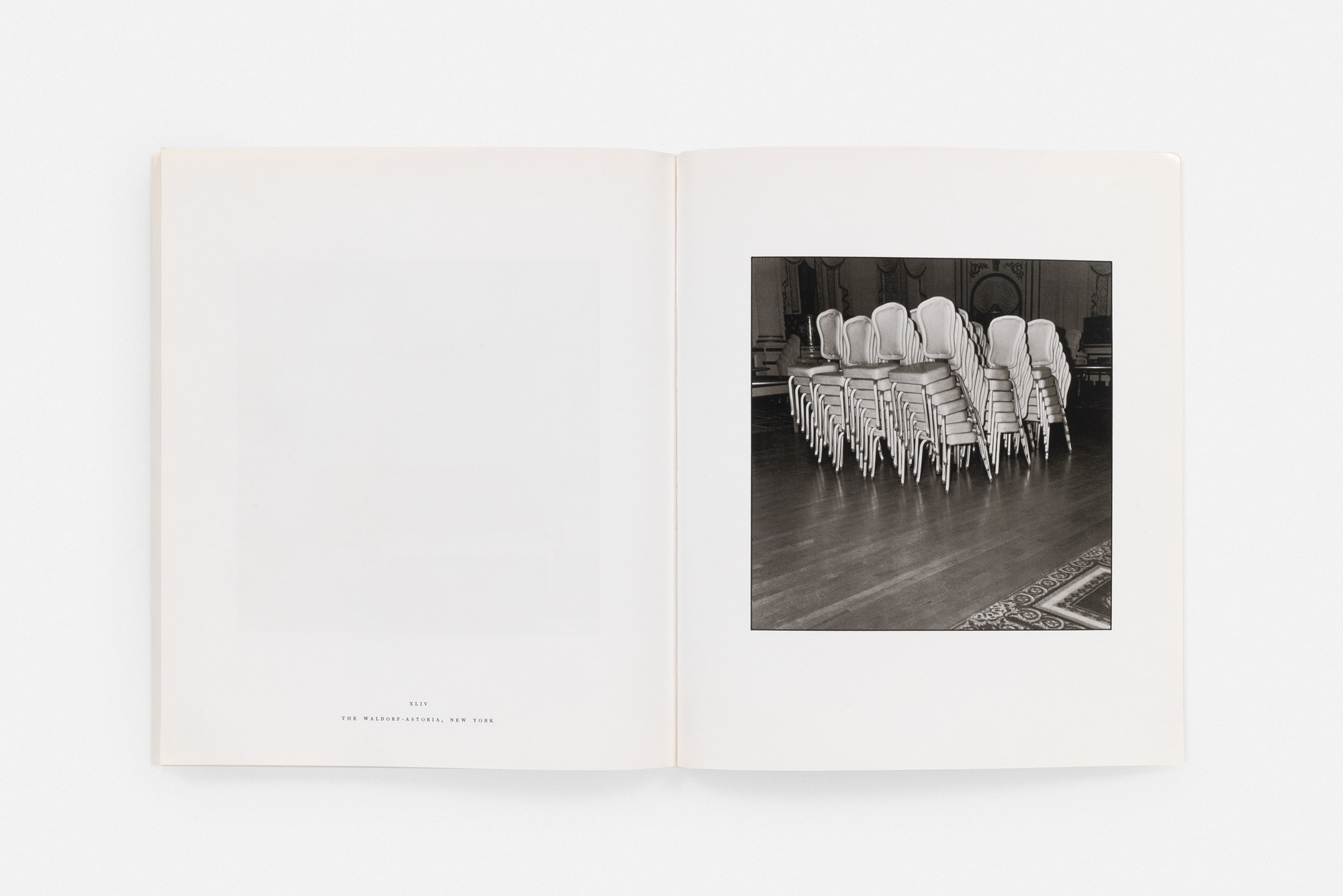

Certainly, the other Diane looms large in the perturbing directness of these photographs. Like Arbus, Keaton favored Rolleiflex cameras, though she was probably less fussy about film type. One especially Arbus-like image finds two cheerless Christmas trees installed atop a pair of tables at the Ambassador, a hotel whose demolition Keaton fought passionately against as a member of the Los Angeles Conservancy. That several of these hotels have since met the wrecking ball or changed to overseas ownership lends the photographs an elegiac air. This quality finds its fullest expression in a phalanx of stacked chairs in the ballroom of the Waldorf Astoria, or perhaps in a photograph of a small dining table, marooned in a sea of plush carpet at what was then the Fontainebleau Hilton in Miami Beach.

Keaton’s interest in photography was wide-ranging. In the late 1970s, she struck up a friendship with the curator and writer Marvin Heiferman, who was then working at Castelli Graphics gallery in New York. They went on to collaborate on several books and exhibitions, including Still Life: Hollywood Photographs (1983), Local News: Tabloid Pictures from the Los Angeles Herald Express (1999), and Bill Wood’s Business (2008), which features the work of a Fort Worth studio photographer whose negatives—all ten thousand of them—had sat in Keaton’s closet for twenty years.

All photographs by Madison Carroll

“She was so smart about pictures,” Heiferman told me. “We would go into archives and sit there and be elbowing each other, laughing, pointing at things, going, ‘Oh wow, isn’t this weird?’” Her taste, he said, helped spur a wave of interest in commercial and vernacular photography. She was an obsessive collector and a habitué of flea markets on both coasts. Her ultimate fantasy, she once told an interviewer, was to purchase every photography book ever published. “My mission is to buy an old warehouse I can transform into a massive library of image-driven books and open it to the public.”

In 2007, Keaton’s friend Larry McMurtry wrote an essay in The New York Review of Books calling attention to her writing on photography. In a letter to the editor, none other than Janet Malcolm chided the Lonesome Dove author for failing to note Keaton’s own work as a photographer. Malcolm praised the “mordant melancholy” of her Reservations images, arguing that they “established her place in contemporary photography” and “form the pendant to Keaton’s wonderful acting career.” Diane Keaton’s place in the photographic canon is hardly assured, of course. She probably wouldn’t mind. Long out of print, Reservations and her other photobooks endure nonetheless, as yet another testament to the compulsive creativity and liberated spirit of an artist who inhabited many different roles in life, all of them herself.