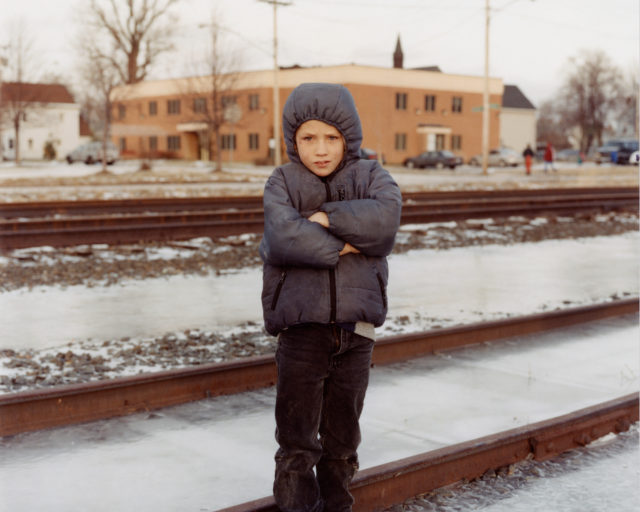

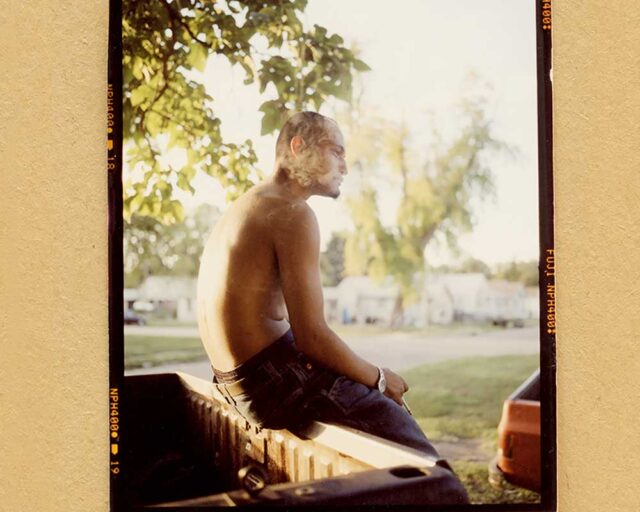

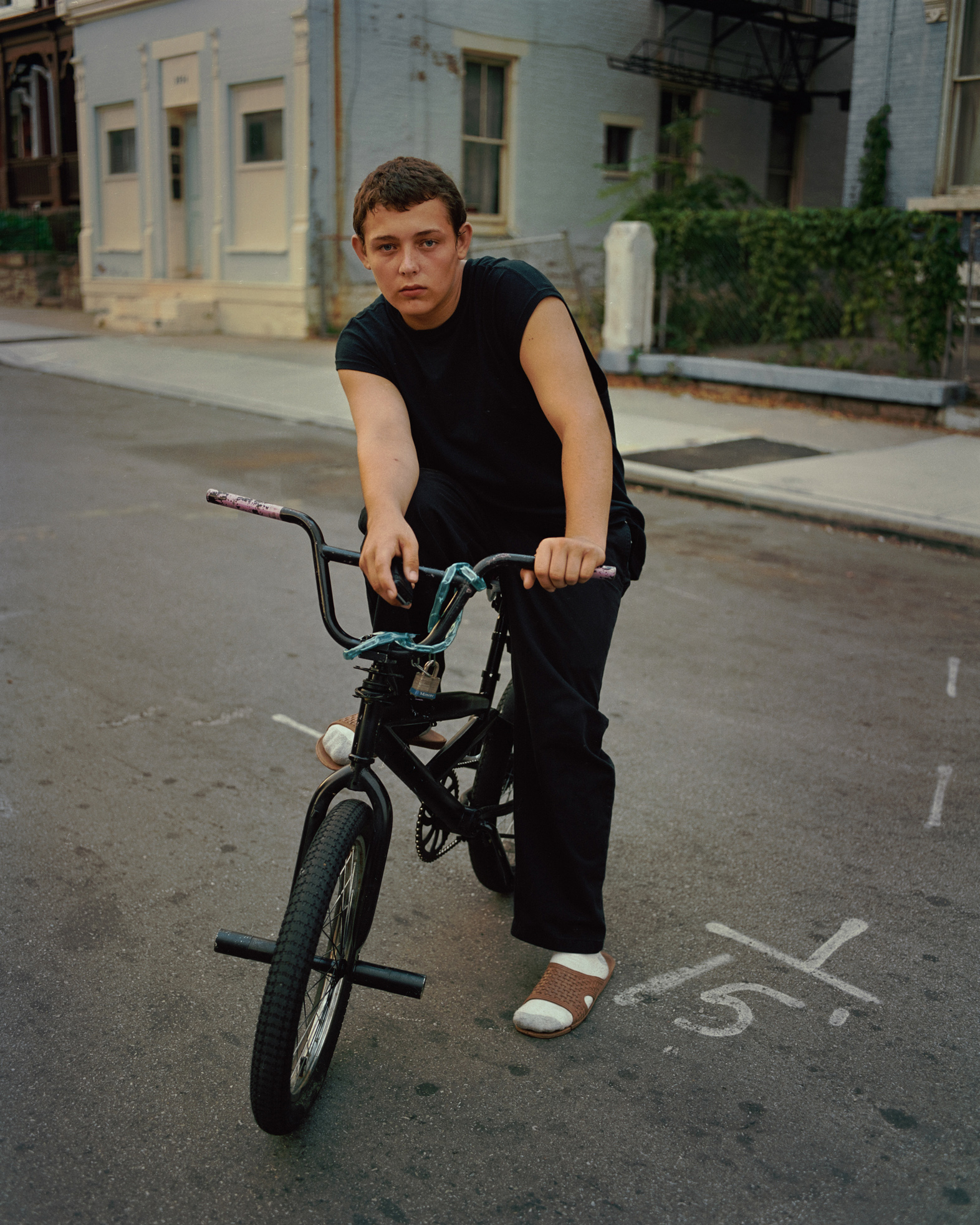

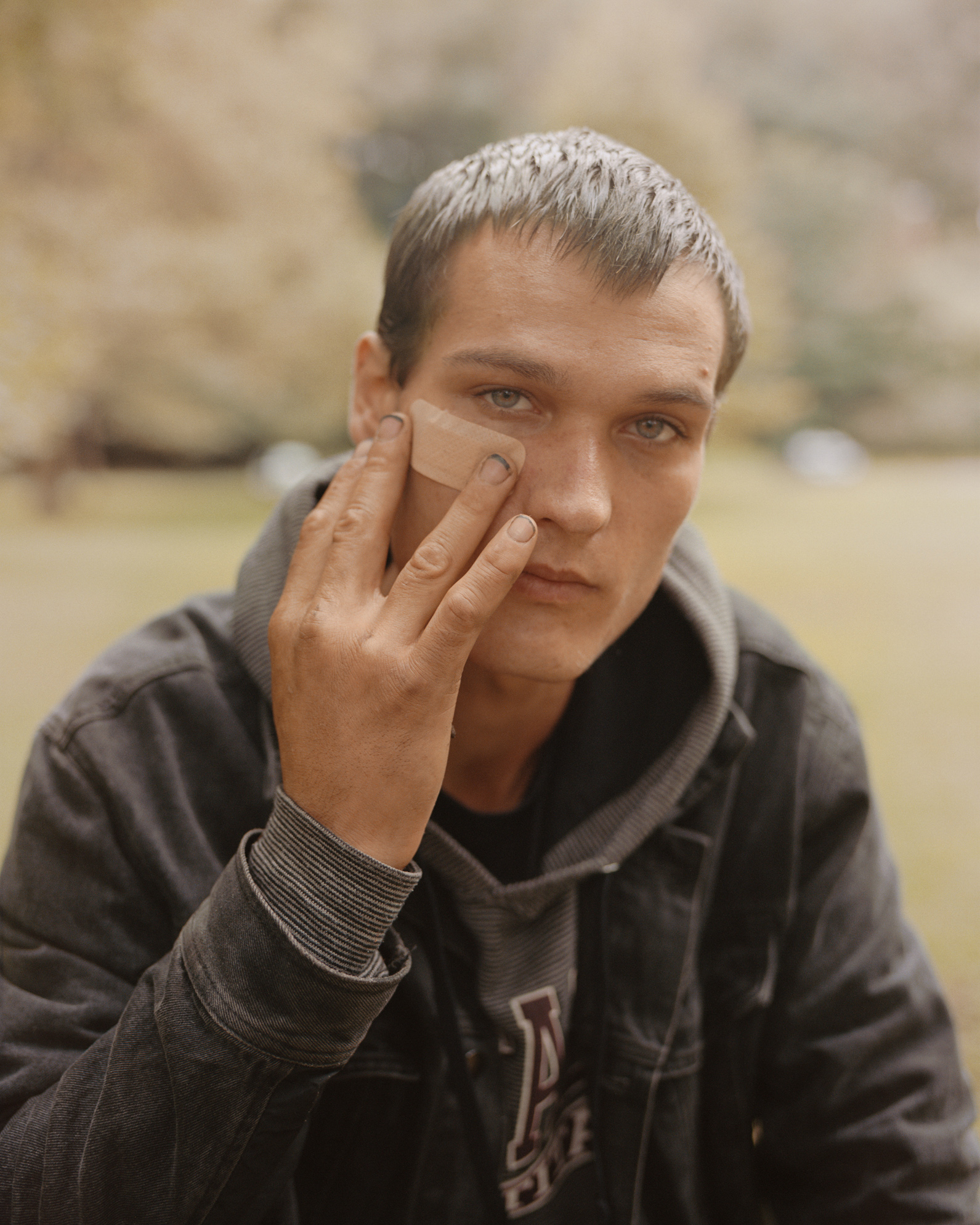

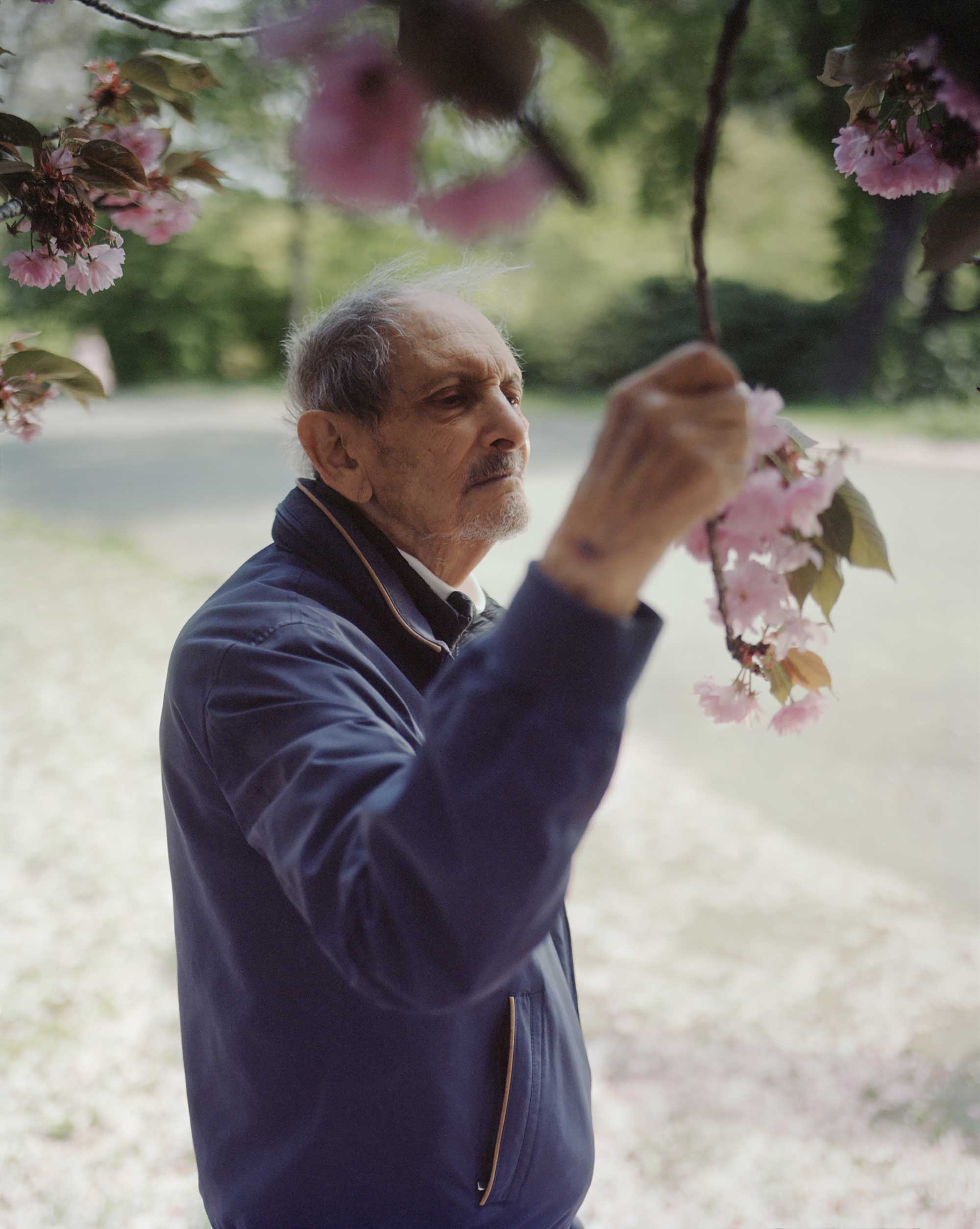

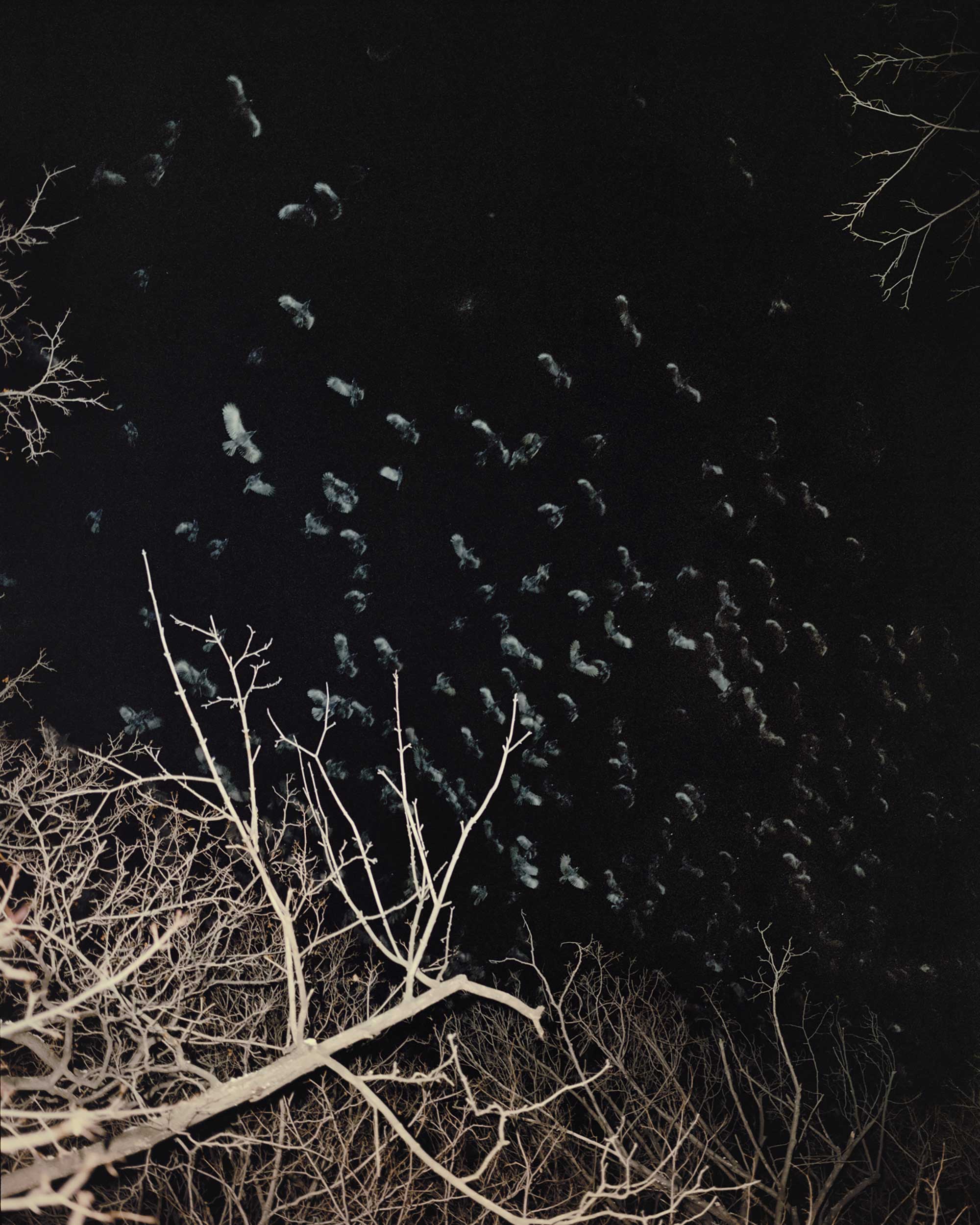

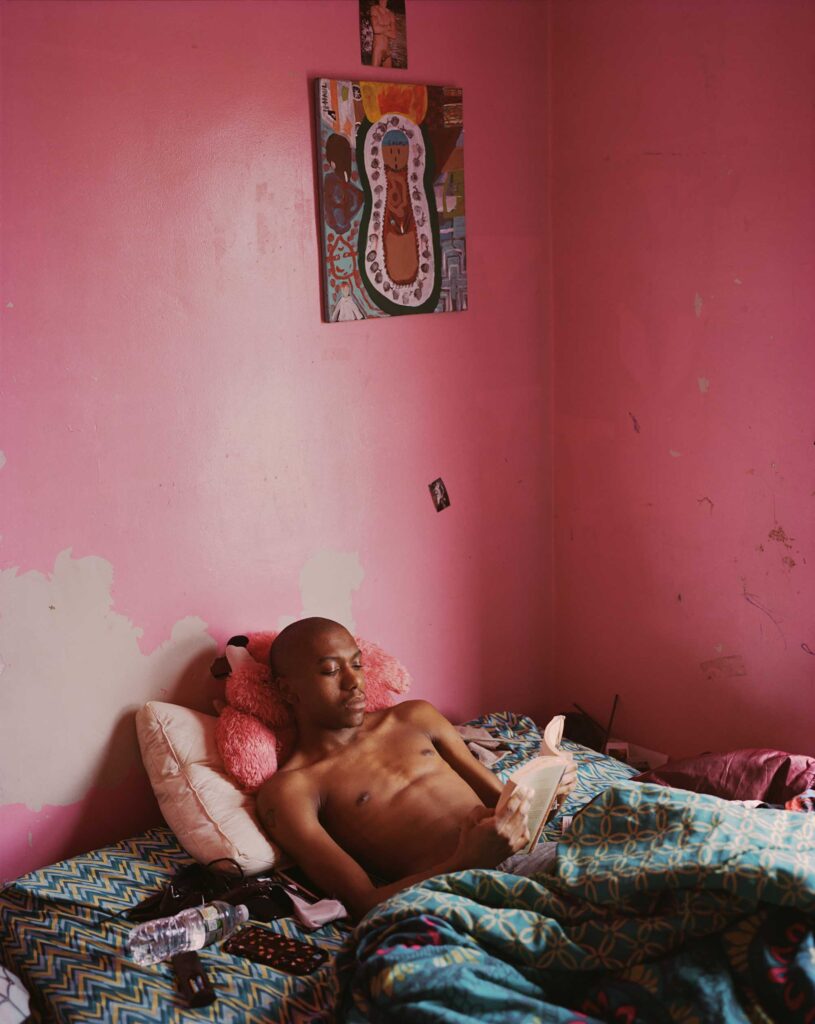

Gregory Halpern, Untitled, from the series 19 winters / 7 springs, 2003–2023

Gregory Halpern has been making photographs in Buffalo, New York, the city where he grew up, for the last twenty years. You could say that Buffalo has been his muse. It’s also been his crucible. It’s a place known for pummeling blizzards and buffalo wings (invented at the Anchor Bar), the Erie Canal and the Martin House (designed by Frank Lloyd Wright), and, of course, the Buffalo Bills. (“Where else would you rather be,” the legendary Bills coach Marv Levy chanted back in 1986, “than right here, right now?”) For Gregory, Buffalo has been a fecund site for childhood exploration, and in his photographs, it is a vast stage across which finely etched characters cross for their cameos: bundled up, making out, climbing up a sledding hill, or lying naked in a silty stream. As the introduction to his solo exhibition 19 winters / 7 springs, curated by Phil Taylor and currently on view at the George Eastman Museum in Rochester, puts it, Buffalo is where “the appearance of everyday reality becomes both volatile and marvelous.”

Gregory’s brother, the journalist Jake Halpern, knows something about Buffalo characters too. He can give you a man’s profile in fifty-one words: “Adrian Paisley spends his days hunting for scrap metal: aluminum, brass and (holy of holies) copper. At 42, Paisley, who weighs just 135 pounds, is wiry and muscular. I once saw him move an old refrigerator by himself, hurling it onto his pickup truck as if it were made of Styrofoam.” That’s from Jake’s story for the New York Times Magazine about the scrap-metal industry. Gregory made the photographs. They’ve teamed up a few times, including for Jake’s rollicking Times Magazine article about freegan squatters. Jake has written about a safe house in Buffalo where refugees from around the world await passage to Canada. Welcome to the New World (2020), his twenty-part graphic series about a Syrian family establishing a new life in the US, with illustrations by Michael Sloan, won a Pulitzer Prize.

Gregory and Jake left Buffalo as young men. There was a sense that in order to succeed, you had to leave. Gregory studied with the photographer Larry Sultan at the California College of the Arts. Jake wrote a book about debt collectors and was a Fulbright Scholar in India. Gregory’s photobook ZZYZX (2016)—named after a desert town east of Los Angeles—heralded a new vogue for contemporary photography’s lyrical documentary style and won the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook of the Year Award in 2016. It’s since become one of the most important photobooks of the last decade; the “Halpern effect” is evident in a generation of young photographers who have studied ZZYZX as though it were gospel. But ZZYZX, Gregory says, wouldn’t have been possible without Buffalo and the time he spent there—nineteen winters, to be exact—honing his voice. Selections from the Buffalo work were first published in Aperture’s “American Destiny” issue in 2017 (he also made the issue’s cover). In his interview with the magazine, Gregory notes that “certain people would say the city is dying, but it’s also continually being born.”

19 winters / 7 springs was presented at the Transformer Station in Cleveland before traveling to Rochester, where Gregory now lives and teaches. Last year, just before Christmas, I spoke with Gregory and Jake about the exhibition. They were together at a cabin in the Adirondacks. “It’s kind of like a guys’ trip this time,” Gregory said. They looked at Gregory’s pictures and spoke about Buffalo with both the fondness and distanced critique that comes from being away for so long. “There are things about your home that you feel forever bound to,” Jake, who now lives in New Haven, said. Yet the city calls them back, continually. As I listened to the Halpern brothers speak about their lives and work in Buffalo, I thought perhaps they never really left.

Brendan Embser: I grew up south of Buffalo, on the border of New York and Pennsylvania, but I haven’t actually been to Buffalo in years, so the key images in my mind are probably the most obvious ones, like the Galleria Mall or the Anchor Bar—or Canisius High School, where we used to go for debate tournaments. So, just to start off, I wonder if you could talk about your upbringing in Buffalo and how the city shaped your worldview.

Gregory Halpern: I’ve always found Buffalo kind of magical, which I realize to some people might sound like a ridiculous statement. I often think about when we were kids, exploring buildings. There were some key amazing buildings that I often think about as the source of my interest in where “realism” and “surrealism” come together. When we were teenagers, we would go to the old psychiatric center where you used to be able to just wander into the building. It was abandoned, but you could go in. Or the old central train terminal. They almost felt like pilgrimages to me. We made little documentaries of our explorations, with this old VHS camcorder. Jake, I don’t know if you have the same sort of feeling about those memories?

Jake Halpern: I totally remember that. I feel like we would get a little crew of friends together and then organize a visit.

Gregory: Were those impactful?

Jake: Yeah. To me, it felt like a version of Dungeons & Dragons. The premise of Dungeons & Dragons is that a group of explorers goes to the outskirts of the town where the ruins are and looks for treasures. One time we were in the Buffalo Psychiatric Center, and a sudden rainstorm came overhead, and because the roof was out, the stairwell was turned into roaring rapids. It was crazy. I think that if you’re growing up in a Midwestern town, and all of a sudden you can go to a place that feels like you’re on the set of Stranger Things—even though Stranger Things didn’t exist then—that was the feeling.

Brendan: Did you grow up in Buffalo proper, or the suburbs?

Gregory: We grew up in an area called North Buffalo. It was near Delaware Park, and there were a lot of beautiful old houses. It was definitely a far cry from the kind of places we’re describing. There weren’t like, ruins around us. It took a while to even kind of know that part of the city existed. I don’t think it was until we were teenagers that we could start to find these places that felt on the periphery of our maps.

Brendan: What is your relationship to Buffalo, now that you no longer live there?

Gregory: Growing up, I feel like there was this notion that if you’re going to “succeed,” you should leave. That’s less so now, because the city is having a bit of a renaissance. But I also remember being sort of pulled back there continually—photographically. I felt like I had something to share, or that I knew something about this place. The further away I got from it, the more unique I realized it felt.

Jake: To be honest, my relationship with Buffalo is complicated in the way that people’s relationships with home often are. There are things about your home that you’re eager to get away from, and there are things about your home that you feel forever bound to. I think it’s taken me much of my adult life to sift through those two opposing dynamics.

We moved there as transplants, because my dad got a job at the university there, and so we didn’t have deep roots in the city. We didn’t have any family there. We had friends, but they were friends that we made as we were growing up, and I never felt a deep connectedness when I was younger in the way that maybe some of our friends did. I think that when I left, like many young people who leave their homes, there was a kind of exhilaration and being out in the great world and thinking, Oh, where I come from is very small, and isn’t it great to see the wideness of the world?

I don’t ever feel like a total insider or a total outsider in Buffalo. But I think that’s been key to me—to have both insider knowledge, but also a little bit of distance.

Yet, as I’ve gotten older, I’m often surprised by the fact that the place has more meaning to me than I even admitted to myself, and like Greg, I’ve come back for stories. Many of the stories I’ve written are Buffalo-based stories: my book Bad Paper (2014), about the debt-collection industry; pieces I’ve written in the New Yorker about the refugees coming through Buffalo; the scrap-metal industry written for the New York Times Magazine. I think, in part, as a writer, the world of stories that are New York–based or LA-based or Chicago-based or Miami-based is just overpopulated, and Buffalo is this greatly overlooked place, but one that I think people are also curious about. It’s a place now that I both know and don’t know. But the older I get, the more I realize that it’s not just someplace in my rearview mirror that I left at eighteen and has nothing to do with me.

Brendan: Where did your family move from?

Jake: My dad and my mom were New Yorkers. Even though I was born in Buffalo, I just didn’t feel of that place. Another layer here is that we are Jews. There is a Jewish population in Buffalo, but it’s in the suburbs. I often say at our high school, City Honors, of one thousand people, I would bet there were maybe no more than ten Jews?

Gregory: Oh, I don’t think it was that many.

Jake: Yeah. Not that we were super-religious or anything. But that also added, for me, a slight otherness feeling.

Gregory: Totally.

Jake: We’ve both become tellers of stories, in a way, whose lives are dependent on being able to talk to people from very different walks of life. Greg had that at a much younger age than I did. He had a very easy time crossing barriers of race, class, clique, in a way that’s pretty unusual for high school. I found my small group of people where I felt I belonged in high school, and I didn’t venture out of that. It wasn’t until later on in my life—maybe even the era when I started returning to Buffalo as a storyteller—when I learned both the ability and also the joy of crossing those divides and telling other people’s stories.

Brendan: Did your parents end up feeling rooted in Buffalo?

Gregory: Our parents split up when I left for college. I’m the younger one. Our mom moved back to New York City, and our dad stayed in Buffalo. He’s totally fallen in love head over heels with Buffalo.

Jake: Our mom kept our house that we grew up in on Woodbridge Avenue for many years. Initially, it was nice to have that house, because there was a place to come home to. But she eventually sold it and built another house in western Massachusetts with Paul, our stepdad. Home is a weird idea. You can hold on to the shell of the house, even when it no longer serves a purpose because you’re tethered by all the memories that exist there. Sometimes you hold on to it so tightly because you want it, but it’s not home anymore, and you really need it to be someplace else. I relate to that kind of tug and pull.

Brendan: That presents a fascinating reading of the three-dimensional work in Greg’s exhibition—the houses with the photographs of the solar eclipses on the interior. Greg, do you feel there’s a psychological aspect to this idea of home as both a shelter, but also as a place from which to look out—to dream of other ways of living?

Gregory: I like that reading. A home is where you sleep, and also where you dream. It’s one of those aspects of life that photography sometimes can’t get to. I was also just thinking about the very simple fact that photographs record the surface of things, literally—like light bouncing off the surface of a thing. Metaphorically, sometimes they only do that, and then sometimes they go deeper. I was thinking about those internal worlds, like the inside of a house that you want to know about, or inside of a person’s dream world that you can’t see with photographs.

Brendan: At what point along the many years of this project did you begin making those 3D works?

Gregory: I made the first house, a little tiny one, over ten years ago now. But it was all four sides. It looked cool, but it looked like a miniature, like a toy or a model, and it didn’t really feel like a work of art. Then, somewhere along the line—I don’t know if I was building it or taking it apart—I had to build two walls at a time. I saw a huge gaping hole in the middle of this house. That’s when this idea occurred to me that seeing the inside was maybe more interesting than just replicating the thing around all four sides.

Jake: To a child, your physical house is your world. It is your universe. On the outside, it may just look like clapboard, but inside, the memories of all the things you’ve explored and discovered for the first time, all the holidays, all the foods you’ve tasted—it’s this kind of wondrous space. I thought your sculptures captured that feeling.

Brendan: The exhibition is called 19 winters / 7 springs. Did you sense at the outset that this would be a long-term endeavor?

Gregory: I started the work when I was in graduate school in California. I was really struggling. Larry Sultan was my advisor, and he pulled me aside and he said, “I think you might need a third year.” It was a two-year program, and I wasn’t going to graduate because I couldn’t find anything in California to photograph. I had nothing to say. I had no idea what to do. But the one thing I feel like I’ve got to offer, or to say that I can claim as my own, was going back to Buffalo in winter. So I took a month in between the semesters, sort of in a panic, and I went back and I photographed every day in winter. That was nineteen years ago. That’s what inspired the title. But the oldest pictures in the book came from that winter.

Brendan: And that’s what pushed you over the finish line for graduate school?

Gregory: Yeah. I was able to get my diploma. Although in retrospect, I feel like a third year with Larry would have been great.

Brendan: As someone from Western New York, my first interpretation of the title was that there were only seven springs, meaning it was so cold for those nineteen years that you only got seven warm seasons.

Gregory: I mean, in a way, yeah, it kind of is that! I first thought of the project as being about Buffalo and winter, because to me, that’s when the city earns its identity, and there’s a really unique feeling there in winter. But then I realized that it was more interesting to mix the other seasons, to create more dynamism in the work.

Jake: I never actually heard you say that, Greg. I didn’t know that when you were out in California, you were struggling to find what your work would be, and you went back to Buffalo. I feel like I’ve done that same thing many times. You want to tell a story, but you ask yourself, What story am I qualified to tell? What story hasn’t been told? When you’re going home to a place, even if you haven’t been there in a long time, there’s some sense of, well, this is my home. I’m not a stranger. When you tell a story, whether it’s through pictures or words, you’re basically an interpreter of place, but you also need to have left that place. I think that’s the commonality between my brother and I—we’re both, in our own ways, interpreters of Buffalo. Which is not to say that we know it better than anyone else. I haven’t lived there in almost thirty years. But maybe what gives me the sense is that I can—or that we can do that.

Brendan: Thanks for saying that. I was also thinking, Jake, about your reporting for the New Yorker on Vive, a shelter in Buffalo that supports asylum seekers. Can you talk about that experience?

Jake: The Vive story came to me through a mutual friend of Greg and ours from high school, Tara Lynch. I was visiting Tara in Austin, Texas, and she said that Vive was almost like an Underground Railroad for refugees. Again, you see the similarity between me and Greg in our worldviews. It felt mysterious and kind of magical, this idea that there’s a secret network that goes through Buffalo into Canada.

Gregory: Jake, you should say a word about who the refugees are. And our family connection to the refugee experience. It’s not related to Buffalo, our family history, but I think it’s related to how we both see the world.

Jake: At the time, Vive was inhabiting an old school building that had been in a significantly abandoned part of Buffalo. These migrants, some of whom were refugees, were hoping to continue to Canada and claim political asylum.

Gregory: Where were they coming from?

Jake: Their paths were incredible. Some could fly to the US on a tourist visa, and they would show up at Vive and get asylum. Others were coming from Eritrea, then ending up in South America, going overland via South America through Central America, showing up at the Mexican border, asking for asylum there, and then coming to Buffalo—all because when they were back in their native land of Eritrea or Mongolia or wherever, someone had told them they could get to this house in Buffalo. That was the part of the story that just blew my mind. But to Greg’s point: Our families were very much immigrants. My great-grandfather stowed away in a boat to come to America. So I think there’s a sense of connectedness to the Vive story, to the sense that an immigrant could end up in a far-flung outpost like Buffalo.

Gregory: Totally.

Brendan: Greg, I’m so intrigued to hear this story about your time in graduate school and your impulse to return to Buffalo. You made a photographic essay over many years about your hometown, but I don’t see it as autobiographical. It’s not full of snapshots or excavations of your family’s past. There’s a lot of restraint in the scenes you chose, and in your decision not to deal with very specific family memories, but to look at Buffalo in the widest possible way. Can you talk about that approach?

Gregory: That’s a great question. I was just looking at the pictures with Jake. There were two pictures that were made, actually, on our high-school playground, that are up now at Eastman, and there are some places and people that we have connections to. But I never wanted to make it specific or personal that way. It just never interested me, and I didn’t think that it would be interesting to others to make it too much about me. I guess it’s about a way of seeing. It’s about feeling my way through the city. In that sense, I feel it’s deeply personal. Somehow, I don’t fully see it until I actually go make pictures of it.

Brendan: It’s like what you said, Jake, about coming back to a place and having a perspective simply because now you’re an outsider.

Jake: There’s one picture in particular that stood out, of a house that’s surrounded by a red-brick building. It’s winter, and the street looks kind of desolate, and there’s snow on the roof. I looked at the photograph, and I did, like, a shiver, like, “Ooh!” It reminded me of this feeling of childhood and Buffalo. There could be, in the depths of winter, this kind of barrenness that not just made you feel cold, didn’t just chill your bones, but made you feel a kind of deep loneliness of trudging through a place that is a little bit forgotten by time.

Brendan: There is something poignant about the way that house seems to be crowded by a school or a municipal building of some sort, but it’s also very clearly a two-family house, because the staircase that’s covered in snow going up to the second floor appears to be the entry to the upstairs apartment. And no one has shoveled out the snow yet, which is a very familiar feeling for Western New York. The other one that struck me is a very modest but lovely little house where there are tulips in front, but also snow on the grass. To me, that’s quintessential Buffalo.

Gregory: I’m so glad you noticed the tulips because I always worry that they get missed. But yeah, that was an amazing moment.

Brendan: Greg, did you feel that the Buffalo work began to give you your photographic language that you later brought to your projects in California and elsewhere? It’s so interesting that you said that you didn’t have anything to say about California, and then you then went on to make ZZYZX, an iconic project about a very specific place in California.

Gregory: ZZYZX was the project where I finally found my voice. In a way, I’ve kind of continued in that tradition since. That took seven or eight years after I moved to California to figure out that I had something to say, and that’s where ZZYZX came from. I was living back in the East Coast when I did that ZZYZX work, and I was living in California when I started the Buffalo work. I think this gets back to what you were saying, Jake: there’s something really helpful about being both an insider and an outsider. I don’t know if the writing world is like this, but the photography world sometimes has this, I think, oversimplified language. Are you a photojournalist outsider? Or are you an insider making work about an identity or an experience that you can claim as your own? There’s a lot of fascinating and important work that sits somewhere in the middle. I don’t ever feel like a total insider or a total outsider in Buffalo. But I think that’s been key to me—to have both insider knowledge, but also a little bit of distance.

Courtesy the artist

Jake: When I saw ZZYZX, I was absolutely blown away because I felt it was a quantum leap forward in your vision and your craft. You basically, to my mind, found a sun-drenched version of Buffalo in Los Angeles. All those themes that were there in Buffalo—the surrealness; the hints of the apocalypse; the biblical, wandering characters with their beards; all this stuff—you found it in this other place. And I had been to LA a lot, but I had never seen it through that lens. This is the lens of Buffalo being trained on some other world, creating some incredible original projection. I think that we both owe Buffalo a lot, in our own ways. It has taught us about the kind of characters and the stories that appeal to us. And it’s really powerful to see what that lens looks like when it’s moved somewhere else.

Gregory Halpern: 19 Winters / 7 Springs is on view at the George Eastman Museum, Rochester, New York, through March 3, 2024.