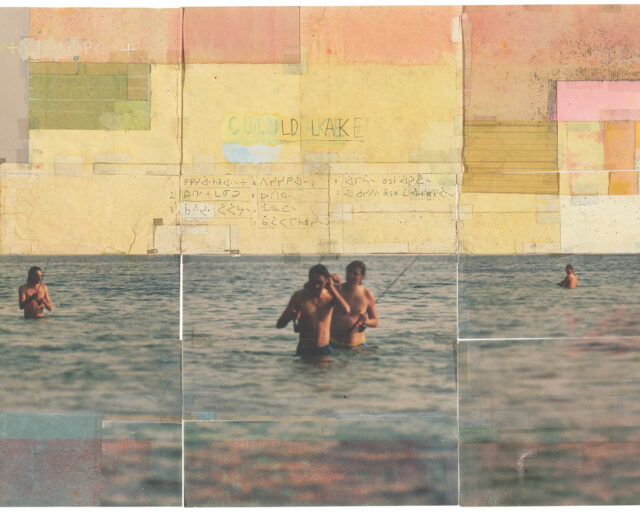

How Indigenous Filmmakers Are Shaping the Future of Cinema

As actors, directors, and communities tell their own stories on-screen, they produce new narratives—and an Indigenous gaze.

Still from Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner, 2001

© Lot 47 Films and courtesy Lot 47 Films/Photofest

In the most iconic scene of Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner, a 2001 film by the Inuk writer, director, and producer Zacharias Kunuk, the titular character sprints butt naked across the spring ice and toward the camera, bounding through frigid puddles and leaping between floes—his nemesis, the wicked Oki, and Oki’s two followers are in hot pursuit and out for blood.

A close-up shows Atanarjuat panting, but determined, shoulder checking Oki every few strides. The unclothed protagonist has put some distance between himself and his attackers, but as he runs away from land, the puddles become more frequent. The harsh Arctic environment appears to have set another trap. Suddenly, Atanarjuat slips and plunges headfirst into a puddle. He stops and collects himself before continuing on. But then, the ghost of the deceased camp leader, Kumaglak, appears. “This way!” he calls to Atanarjuat. “Over here!” Atanarjuat sprints toward a gap in the ice, leaps across the water, and lands on both feet. In a twist of fortune, Oki slides through a hole in the ice. His henchmen have to call off the chase to pull him from the water. “I won’t sleep till you’re dead!” cries Oki, panting. His revenge against Atanarjuat for marrying Atuat, the woman to whom Oki was promised, has been foiled. The camera cuts to Atanarjuat, still bounding across the ice, his body shrinking to a tiny speck against the Arctic sunset.

When the credits roll, a behind the-scenes clip reveals the labor that went into making this scene: a camera mounted on a sled is dragged by a crew running ahead of Natar Ungalaaq, the actor who plays Atanarjuat. In a 2017 interview for the CBC show The Filmmakers, Ungalaaq said he kept warm while shooting the scene by huddling near a stove inside a tent and making coffee between takes. “In my mind, nobody wanted to get that role—naked in front of camera,” Ungalaaq recalled.

Courtesy Igloolik Isuma Productions

And that was to shoot just one scene. The entire film was produced with a budget of 1.9 million Canadian dollars. Kunuk started by gathering eight elders’ retellings of the Atanarjuat legend. Then, Kunuk and five writers synthesized these versions of the story into a script in both Inuktitut and English, consulting with Inuit elders to maintain cultural integrity. They trained Inuit locals from the Canadian territory of Nunavut in all the on-set jobs needed to make a feature film: makeup, sound, stunts, special effects. For a community with an unemployment rate around 50 percent when the film was made, Atanarjuat created economic opportunity. All the while, Kunuk endeavored to have the story pull the audience into the emotionally rich and socially complex interior of Inuit life. “The goal of Atanarjuat is to make the viewer feel inside the action, looking out, rather than outside looking in,” reads a post labeled “Filmmaking Inuit Style” on the website for Isuma, the Inuit production company that made the film. “Our objective was not to impose southern filmmaking conventions on our unique story, but to let the story shape the filmmaking process in an Inuit way.”

Based on an ancient Inuit folktale and set in the village of Igloolik, in what is now the Canadian territory of Nunavut, Atanarjuat was the first feature-length film made entirely in the Inuktitut language. It was also the first Canadian motion picture to win the Caméra d’Or at the 2001 Cannes Film Festival, and it was ranked the best Canadian film of all time in a 2015 poll conducted by the Toronto International Film Festival.

I first saw Atanarjuat at the San Francisco American Indian Film Festival when I was eight years old. And I was confused for at least half the movie because I was under the impression that it was about another fast runner: the legendary Native American athlete Jim Thorpe. (I recall whispering to my mom during the ice chase, “When are they going to the Olympics?”) Though I was disappointed that Atanarjuat wasn’t a sports movie, the film left an impression on me and on many other Native people. To this day, it is still unusual to make a film where Indigenous people are in front of the camera, much less one where they’re behind it. A generation of Native filmmakers now cites Atanarjuat as a work that inspired them. Kunuk and Isuma have helped other Indigenous communities, directors, and actors tell their own stories on-screen—producing not only Indigenous narratives but also an Indigenous gaze.

© Pathé Exchange Inc. and courtesy Pathé/Photofest

Despite the accolades, Kunuk’s and the Inuit’s contributions to the history and future of film remain largely unheralded. To fully appreciate the significance of Atanarjuat, you first have to understand the film it is in conversation with: Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North. Released in 1922, Nanook of the North was a pathbreaking film that some consider to be the first documentary ever made. This designation, however, comes with a heavy asterisk.

Flaherty filmed Nanook of the North between 1920 and 1922. His intention was to portray Inuit culture to white audiences before what was left of traditional life was obliterated by Western modernization. The film follows a celebrated hunter, framing scenes of Inuit labor as though they were dioramas in the American Museum of Natural History. There are scenes of Nanook rowing a kayak, traversing ice floes in search of game, trapping Arctic fox, building an igloo, teaching his son to hunt with bow and arrow, eating raw seal meat, glazing the runners of his sled, harpooning a walrus, and fighting a seal, among many other events. There’s even a part early on where Nanook visits a trading post owned by a white merchant who shows the Inuit a gramophone. Nanook, apparently ignorant of the technology, attempts to bite the record, adding a moment of comic relief undoubtedly designed to make white audiences laugh at him.

Like an anthropologist, Flaherty plays the role of informant, homing in on the Inuit mode of production. But like an artist, he pauses to admire the austere beauty of the Arctic and the Inuit’s ingenuity in living amid it. Every so often, the silent film pauses to interject Flaherty’s written narration, which oscillates between these registers. In the final scenes of the film, Flaherty seems to push beyond these self-imposed limits. His camera captures Nanook savoring a bite of raw seal meat as his wife, Nyla, swaddles their child before leaning in to rub noses with the babe: an “Eskimo kiss.” “The shrill piping of the wind, the rasp and hiss of driving snow, the mournful howls of Nanook’s master dog typify the melancholy spirit of the North,” reads Flaherty’s narration as his camera captures nightfall on the windswept landscape outside Nanook’s igloo.

But here’s the thing: it’s all staged. Nanook is actually a guy named Allakariallak, a veteran hunter from the Itivimuit Inuit whom Flaherty had befriended. The seal Nanook fights on-screen is actually already dead. And by the time Flaherty arrived, many Inuit were well adapted to Western technology. Although Flaherty insisted Allakariallak and the cast wear traditional clothing, the Inuit usually wore a hybrid of Western and Inuit attire. While Flaherty’s Nanook hunted with a harpoon, Allakariallak preferred the firepower of a gun. And while Allakariallak played dumb around the gramophone on screen, in real life, he was well aware of the technology and how it worked.

© Pathé Exchange Inc. and courtesy Pathé/Photofest

It’s tempting to call Flaherty a fraud and leave it at that. But on the set of Nanook of the North, the Inuit weren’t just paid actors; they were consultants and production staff. Nyla, Nanook’s young wife, was actually Flaherty’s common-law wife; they had a child together. In Inukjuak and Grise Fiord, in Nunavut, there is still a thriving clan of Inuit with the last name Flaherty. Jay Ruby, an anthropologist, has argued that Flaherty collaborated with the Inuit on set. “The Inuit performed for the camera, reviewed and criticized their performance and were able to offer suggestions for additional scenes in the film—a way of making films that, when tried today, is thought to be ‘innovative and original,’” writes Ruby.

Faye Ginsburg, an anthropology professor at New York University, and Fatimah Tobing Rony, a professor of media studies at the University of California, Irvine, have gone even further, claiming that the Inuit served as camera operators. The Akeley cameras Flaherty used were hefty sixty-pound, hand-cranked devices that required a fifteen-pound tripod—all of which, along with massive quantities of 35mm film, needed to be lugged across snowbanks, ice floes, and Arctic waters. And as the film critic Roger Ebert pointed out in a four-star review for the Chicago Sun-Times: “If you stage a walrus hunt, it still involves hunting a walrus, and the walrus hasn’t seen the script.”

These facts would seem to cast Nanook of the North, and perhaps even the whole early history of documentary and nonfiction film, in a different light. If the Inuit were behind the camera—and not merely prehistoric stock characters in the national imaginary—then we must consider the possibility that the prodigious body of work inspired by Nanook of the North was inspired not just by Flaherty’s artistic talents but also by those of his Inuit collaborators. Indeed, many Inuit have long been proud of the work, perhaps aware of their peoples’ contributions to it. And it is perfectly understandable that Inuit audiences would take some pride in seeing their culture—which, like many Indigenous cultures, has been battered by colonization—celebrated on-screen.

In fact, after watching and researching the film, I started to wonder if the paradigm of salvage anthropology was actually an appropriation of the deeply Indigenous desire to preserve and remember the beauty of Native life before the cataclysm of colonization. “The film excited great pride in the strength and dignity of their ancestors, and they want to share this with their elders and children,” Lyndsay Green, operations manager of the Inuit Tapirisat of Canada (now called the Inuit Tapirisat Kanatami), the national governing body representing Inuit in Canada, said of Nanook of the North, which the Inuit Broadcasting Corporation screened into the 1970s. But then, we must also consider the dismissiveness with which Flaherty later addressed his Inuit actors, collaborators, and lovers. “I don’t think you can make a good film of the love affairs of the Eskimo,” he said in a 1949 interview with the BBC, “because they never show much feeling in their faces, but you can make a very good film of Eskimos spearing a walrus.”

© Igloolik Isuma Productions and courtesy Niijang Xyaalas Productions

The greatest achievements in creative and intellectual pursuits often entail killing the master: to Plato’s ideals, Aristotle responded with empirics; to Richard Wright’s Native Son, James Baldwin responded with a vicious takedown of his friend and mentor’s novel, collected in Notes of a Native Son; to Jay-Z’s “Takeover,” Nas responded with “Ether.” And for Nanook of the North, there’s Kunuk’s Atanarjuat.

A close examination reveals that Kunuk co-opted many of Flaherty’s creative ticks. Atanarjuat was made with a desire to preserve Inuit culture—but Kunuk does it for an Inuit audience, while Flaherty did it for a white one. And Kunuk’s camera moves in a way curiously similar to Flaherty’s. Kunuk shoots his subjects up close, taking time to pause and let the labor and land of the Inuit unfold for the viewer—inviting the audience to move to the rhythm of Inuit life. In one of the first scenes, where the village is cursed by Tungajuaq, a shaman from the north, the polar bear necklace of the shaman is brought right up to the camera, as though the lens is the viewer’s neck. But instead of narration, Kunuk turns to shamanic fortune and fate to explain the twists and turns of his narrative. It’s not a stretch to view Tungajuaq—a strange and evil outsider—as a metaphor for European colonization.

And yet, in this narrative, Europeans are even denied the right to intrude. Kunuk reclaims many of Flaherty’s conventions—perhaps the same ones that could more accurately be attributed to his Inuit collaborators—to produce what I might describe as an Inuit gaze: a visual style and sensibility particular to his Inuk viewpoint. Like the shaman in his story, he playfully wags a finger at Flaherty at every turn. He even does the very thing Flaherty said the Inuit couldn’t do: make a movie about love. Indeed, the central drama of Atanarjuat—the thing that sets Oki at the protagonist’s throat—is the passion between Atuat and Atanarjuat. This is what makes Kunuk’s film a triumph in the fullest sense: like Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse at the Battle of the Little Bighorn, Kunuk has slain a white giant, for all to see.

© Igloolik Isuma Productions and courtesy Niijang Xyaalas Productions

Over the past twenty years, Kunuk and his production company, Isuma, have schooled many Indigenous filmmakers, such as the brothers Gwaai and Jaalen Edenshaw, who cowrote the 2018 film SGaawaay K’uuna (Edge of the Knife), the first movie made entirely in the Haida language. And like Kunuk and the Inuit, the Edenshaws and the Haida were drawn to film as a tool to preserve their endangered language and culture. With their cameras, this new generation of filmmakers is capturing Indigenous worlds imperiled but resilient. Like the Inuit who worked with Flaherty a century ago, these filmmakers are asking some of the biggest and most important questions: What is the responsibility of the filmmaker to his or her community? How do we tell stories about worlds collapsing under the weight of colonization, resource extraction, mass extinction, and climate change? And who has the right perspective to tell those stories? This spring’s unseasonably warm weather—the warmest on record since at least 1958—brought an early melt season to the Arctic. The location where Natar Ungalaaq once bounded across the ice as Atanarjuat will soon be unfit to film such a scene, and likely unrecognizable to Kunuk, the Inuit, and all who have come to properly appreciate their films as well as their monumental contributions to art on this shattered earth.

This essay originally was originally published in Aperture, issue 240, “Native America,” under the title “The Indigenous Gaze.”