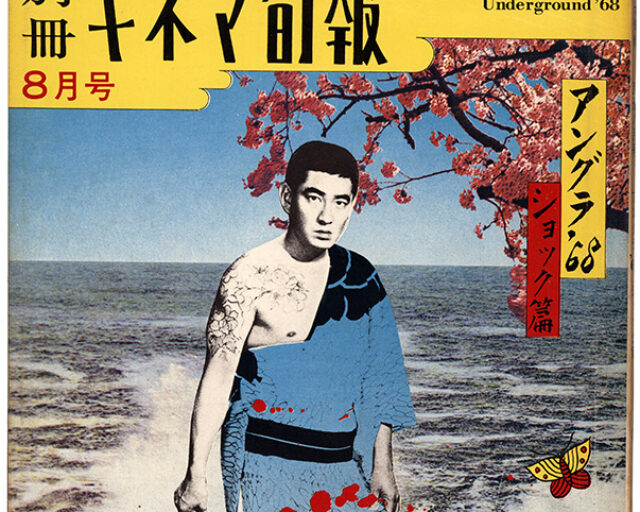

Cover of Asahi Graph by Kishin Shinoyama, featuring Yoko Ono, August 1974

If the average Japanese person was asked to name a photographer, they might first answer: Kishin Shinoyama. Starting in the 1970s, Shinoyama was a constant presence in Japanese photography magazines, but by the 1990s his fame had grown and he became a public figure in Japan, known for his well-produced images of celebrities. John Lennon, Yoko Ono, Yukio Mishima, and nearly all glitterati, as well as anyone and everyone of note in the world of Japanese culture, sat before his camera.

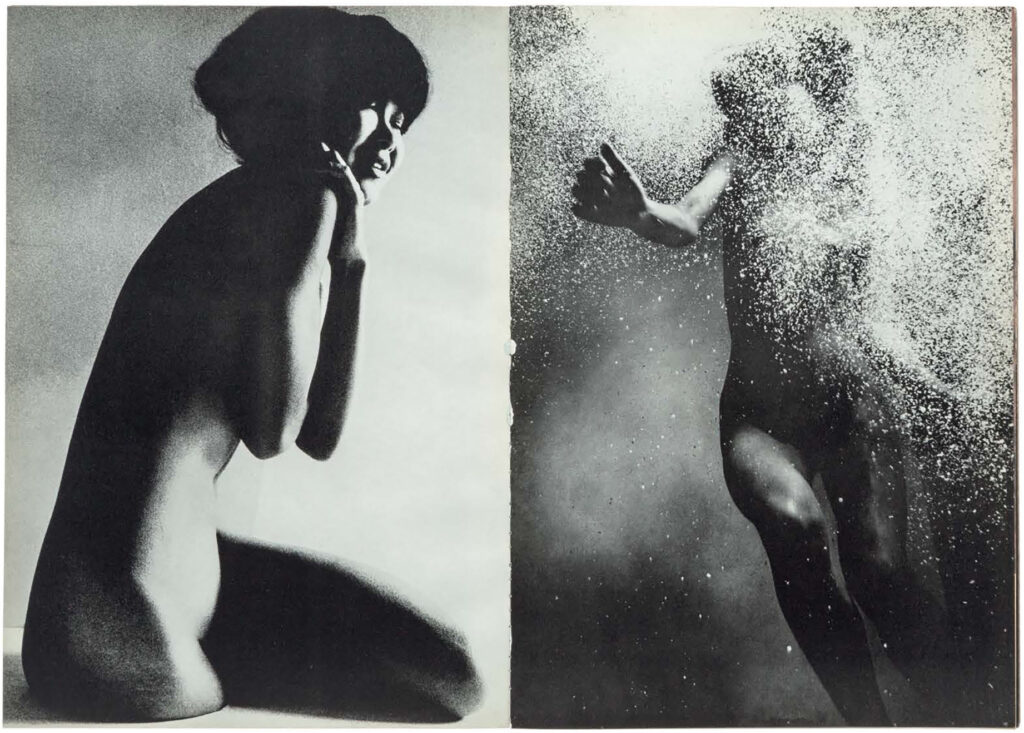

However, what first earned his broad recognition were his nudes. Gekisha was a series featured in Goro, a weekly men’s magazine published by Shogakukan between 1974 and 1992. These images fit into the category of “gravure,” a term used in Japanese magazines for nude pinups. Shinoyama’s gravures stood out because of his selection of well-known actresses and models as subjects. The term gekisha, which Shinoyama coined, combines the kanji for intense and shoot, suggesting a photograph crafted as a spectacle. The success of the series led to the 1979 release of Gekisha: 135 Female Friends, which purportedly sold hundreds of thousands of copies. Buoyed by these impressive sales, Shogakukan debuted the monthly magazine Sharaku (1980–85), featuring Shinoyama as the principal photographer.

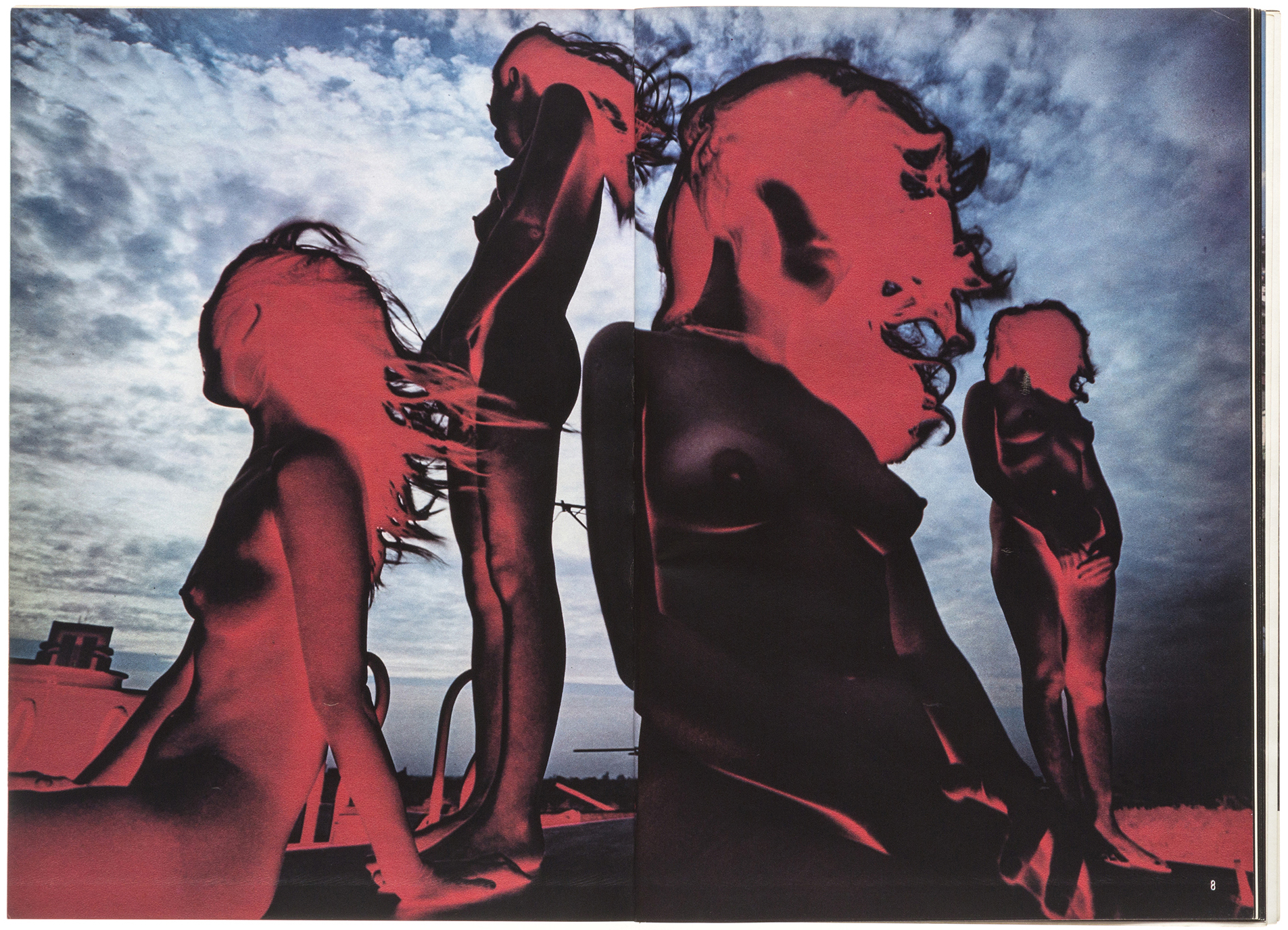

Despite the relatively demure nature of Shinoyama’s nudes, his work began to court controversy in 1985 after he published the photobook Pygmalionisme (Bijutsu Shuppan), which features photographs of dolls created by the artist Simon Yotsuya. Some of Yotsuya’s dolls feature pubic hair, which at the time was deemed obscene. Japan enforces laws regulating the publication of obscene material, and throughout the 1980s, what constituted “obscene” underwent an incremental revision process. Publishers regularly gambled with how far they could push the boundary between artistic expression and pornography.

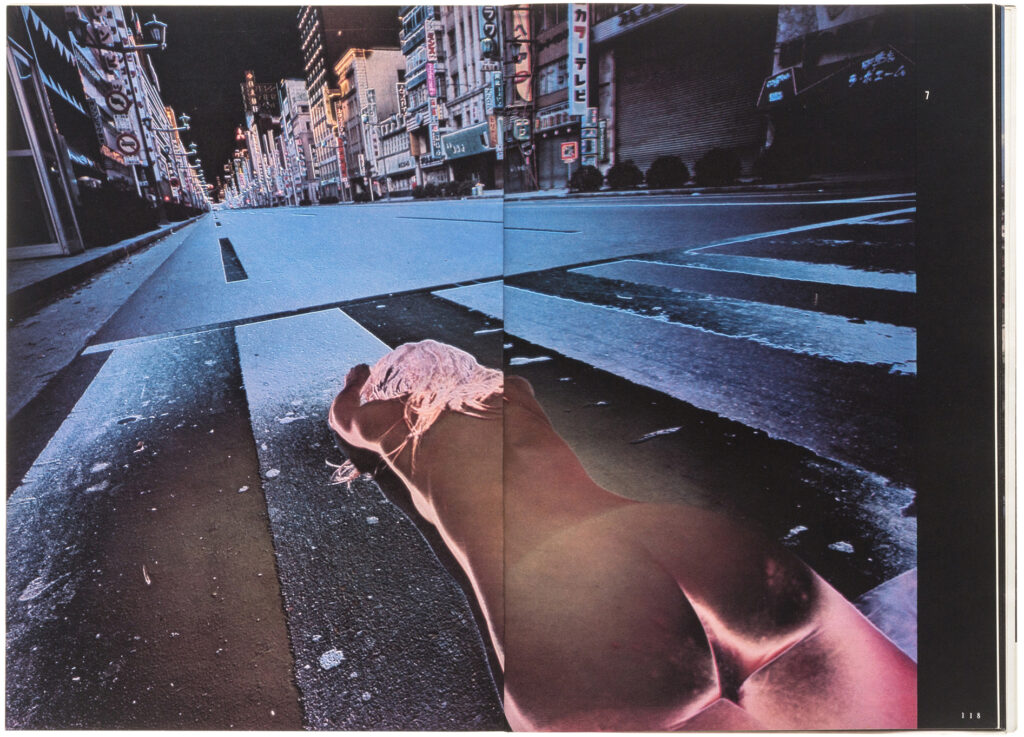

The year 1990 proved to be a watershed moment for Shinoyama. He released Tokyo Nude, published by Asahi Shimbun Company, one of Japan’s main newspaper companies. News of the photobook’s publication even made broadcast television. The book is comprised of cityscapes of Tokyo shot at night or in the early hours, with streets deserted save for nude models standing within the landscape, positioned like mannequins. What shocked many about the book was the presentation of the naked form against the utterly mundane views of the megalopolis. This was a prelude to the publications that would elevate Shinoyama to broad recognition.

The following year, Shinoyama published Water Fruit (Asahi Press), featuring nudes of the actress Kanako Higuchi. A few months later, the attention the book garnered was soon overshadowed by that of his next photobook, Santa Fe, which features the actress Rie Miyazawa, known for her modeling career since early adolescence. At the time of Santa Fe’s publication, she was said to have been underage during the photoshoot. Such incidents of the 1980s and 1990s have become defining elements in the public perception of Shinoyama’s oeuvre. However, it would be a disservice to his diverse oeuvre to confine it solely to this brief period. His career spanned sixty years wherein he found a balance between commercial and artistic pursuits and was deeply engaged in the discourse on photography.

Shinoyama would not have an exhibition at the prestigious Tokyo Photographic Art Museum until 2021, because the museum maintained a hardline stance against showing the work of a “commercial” photographer. It exhibited the series Hareta no hi (A fine day), which dates from 1975 and has been published as a photobook with the same title. Upon receiving a copy of the book, the photographer Takuma Nakahira, a founding member of the influential 1960s collective Provoke, is said to have been reinvigorated about the potential of photography. In Shinoyama’s work, Nakahira saw something unique. This led to their yearlong collaboration in 1976, during which they created the twelve-part series Ketto shashinron (A duel of photography theory) for the magazine Asahi Camera, featuring photographs by Shinoyama and writings by Nakahira.

That same year, Shomei Tomatsu, Eikoh Hosoe, and ten other photographers put together an exhibition called Shashin urimasu (Photos for sale), held at a boutique in Tokyo’s posh fashion district. At the time, there was a hardly a market for photography in Japan, so this project was planned to find meaning in the buying and selling of prints. But Shinoyama was having none of it. In response, he held the exhibition Shashin agemasu ten: Marī no natsuyasumi (Photos for free: Marie’s summer vacation), featuring a model on holiday, at the now defunct Minolta Photo Space. One camp posited photography as an object-based fine art that could have market and archival value; the other saw the photographic print simply as what was given to a publisher for mass reproduction.

Much photography in Japan has now been subsumed within the category of art, as signified by the renaming of the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography to the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum in 2016. This shift in vision prompts reflection on what might be obscured by this type of recategorization. Historically, experiencing photography through magazines and as an element of mass media has shaped our general understanding of the medium, especially in Japan, where print culture has thrived. By redefining photography narrowly as art, we risk losing sight of its broader context, influence, and potential. Perhaps Shinoyama’s legacy—in addition to being the face of an epoch in Japan’s photographic history and his reputation as a provocateur—offers a counterpoint to prevailing norms regarding what defines a photograph’s value and significance.