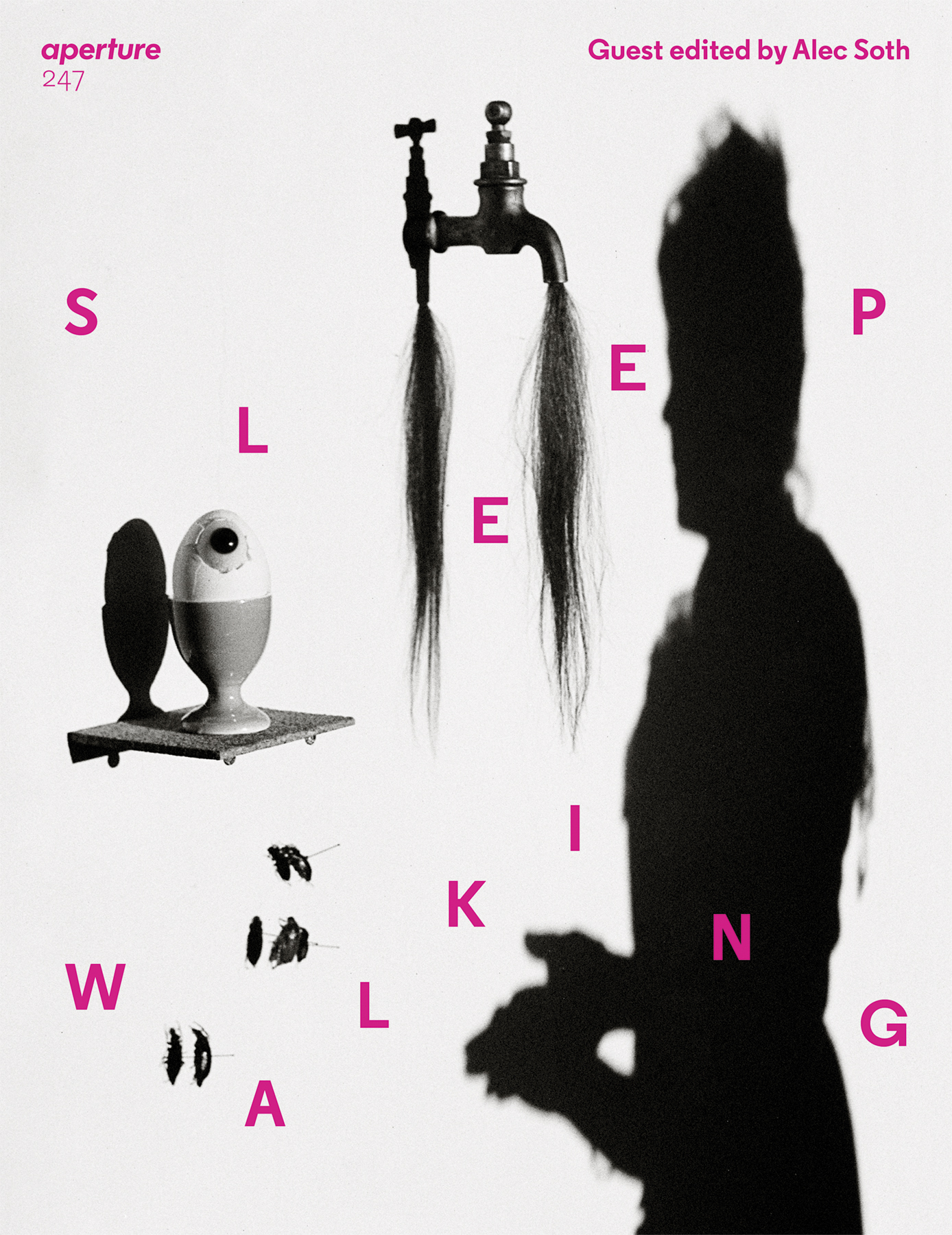

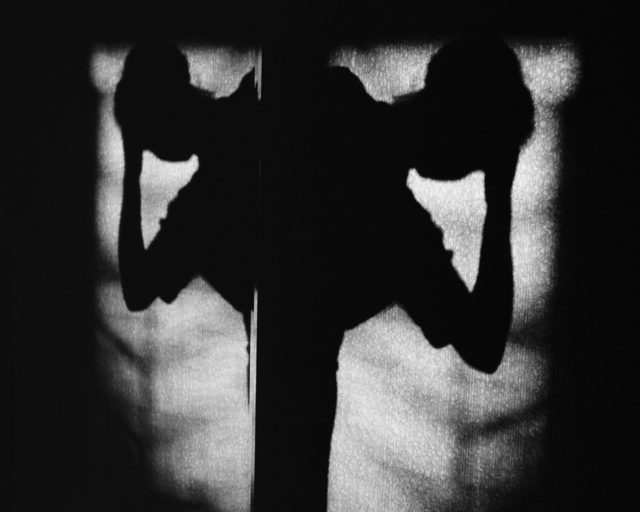

David E. Scherman, Lee Miller (Mirror Series), Downshire Hill, Hampstead, London, 1946

“One could say that Lee’s feel for the incongruities of daily life made her a Surrealist,” writes Lee Miller’s biographer, Carolyn Burke. Although she was never an official member of the group (according to Burke, she couldn’t abide André Breton), her feeling for incongruity and unexpected juxtapositions, for dreamlike imagery and tears in consciousness, her ability to perceive instabilities in apparently ordinary scenes, and her ethical commitments to getting the picture against all odds make her one of the movement’s great photographers.

Miller was surrounded by Surrealist men in both her personal and professional lives. Her mentor turned lover, Man Ray, introduced her to Surrealist art and artistic circles in late 1920s Paris; she starred in Jean Cocteau’s The Blood of a Poet (1930); her second husband, Roland Penrose, was an established practitioner of Surrealism in Britain and later a cofounder of the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London. But while these influences were important to her, Miller had her own decided view of the world. “I think she’s a Surrealist from the beginning to the end,” says Patricia Allmer, author of Lee Miller: Photography, Surrealism, and Beyond (2016).

In The Lives of Lee Miller (1985), recently rereleased in paperback, her son, Antony Penrose, depicts his mother as a woman who bolted from adventure to adventure, who “rode her own temperament through life as if she were clinging to the back of a runaway dragon.” Born in Poughkeepsie, New York, in 1907, Miller got started with photography by having her picture taken hundreds of times—often nude—by her father, an amateur photographer with a darkroom tucked under the stairs of the family house. She continued modeling as a young woman in New York City, appearing on the cover of the March 1927 issue of Vogue within months of her meet-cute with Edward Steichen of Condé Nast (she stepped in front of a moving cab; he yanked her out of harm’s way). She became one of his favorite models. In Steichen’s viewfinder, Miller looks modern and eternal at the same time—Baudelaire’s own definition of beauty. However, as Miller herself would later recall, “I looked like an angel, but I was a fiend inside.”

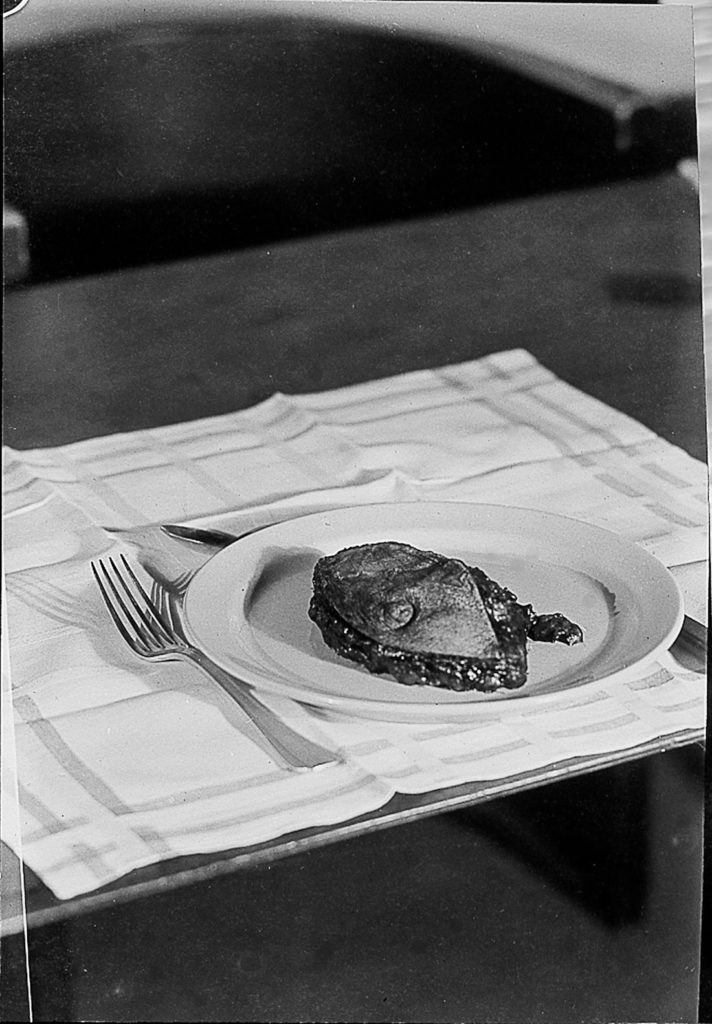

The angel paid the bills, but the fiend wanted to hold the camera herself. In 1929, she got on a boat and tracked down the photographer Man Ray in Paris. “I’m your new student,” she told him. He didn’t take students, but he took her. For three years, they lived and worked together; Miller learned everything she could about making and developing pictures. He would sometimes pass assignments to her; as the story goes, Miller was at the Sorbonne medical school photographing something for Man Ray when she witnessed a mastectomy procedure. She took the severed breast to the offices of Vogue and photographed it on a dinner plate before she and the breast were thrown out.

Miller’s Surrealism has to do with her ability to look “awry” at the world, says Allmer. For instance, there is the striking image of a woman’s hand reaching for the doorknob as seen through the scratched shop window at Guerlain, which Miller calls Untitled (Exploding Hand) (ca. 1931). She captures otherwise imperceptible moments like this and, in spite of their ordinariness, finds great drama. There is an element of chance in this picture, but there is also an alertness to the potential readings of the work that is all her own.

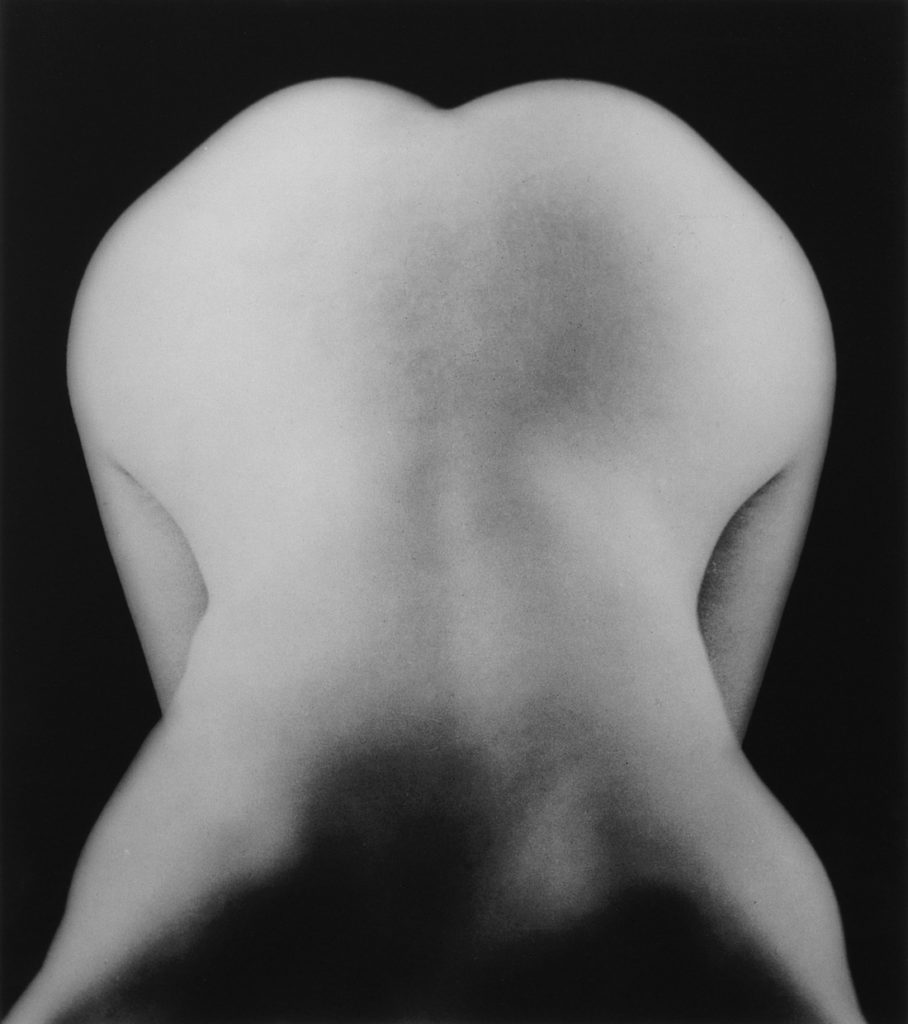

By contrast, a studio image such as Nude Bent Forward (ca. 1930) clearly involved planning and forethought to set the camera and the lighting in just the right way so that when the model leaned over, naked, her torso would fill the frame, arms and neck cut off, the lower half of her body seeming to disappear into the shadows below. As Mary Ann Caws, author of Surrealism (2004), writes, the composition creates “the disquieting effect of making the body appear gradually to be dissolving.”

The female body—so fetishized in Surrealist art—is almost unrecognizable in Nude Bent Forward. That we are looking at a body is clear; the grain of the skin has been beautifully, duskily rendered. But it is also contorted beyond recognition; there is something troubling in its visceral ambiguities.

In 1934, having left Man Ray and resettled in New York to start her own studio two years prior, Miller married the Egyptian businessman Aziz Eloui Bey, eventually moving with him to Cairo. The time she spent in Egypt was crucially important to her development as a photographer. In Portrait of Space (1937), her Surrealist gaze could see a whole world of suggestion in the torn and tattered mosquito net, the tent’s window seeming to hang askew like an empty frame. The scholar Katharine Conley writes in Surrealist Ghostliness (2013) that the emptiness of this frame “resembles the ‘unsilvered glass’ of Breton and Soupault’s Magnetic Fields that metaphorically divides a body’s psychic unconscious from consciousness, separating outer from innermost realities.”

Miller’s Surrealism has to do with her ability to look “awry” at the world. She captures otherwise imperceptible moments and, in spite of their ordinariness, finds great drama.

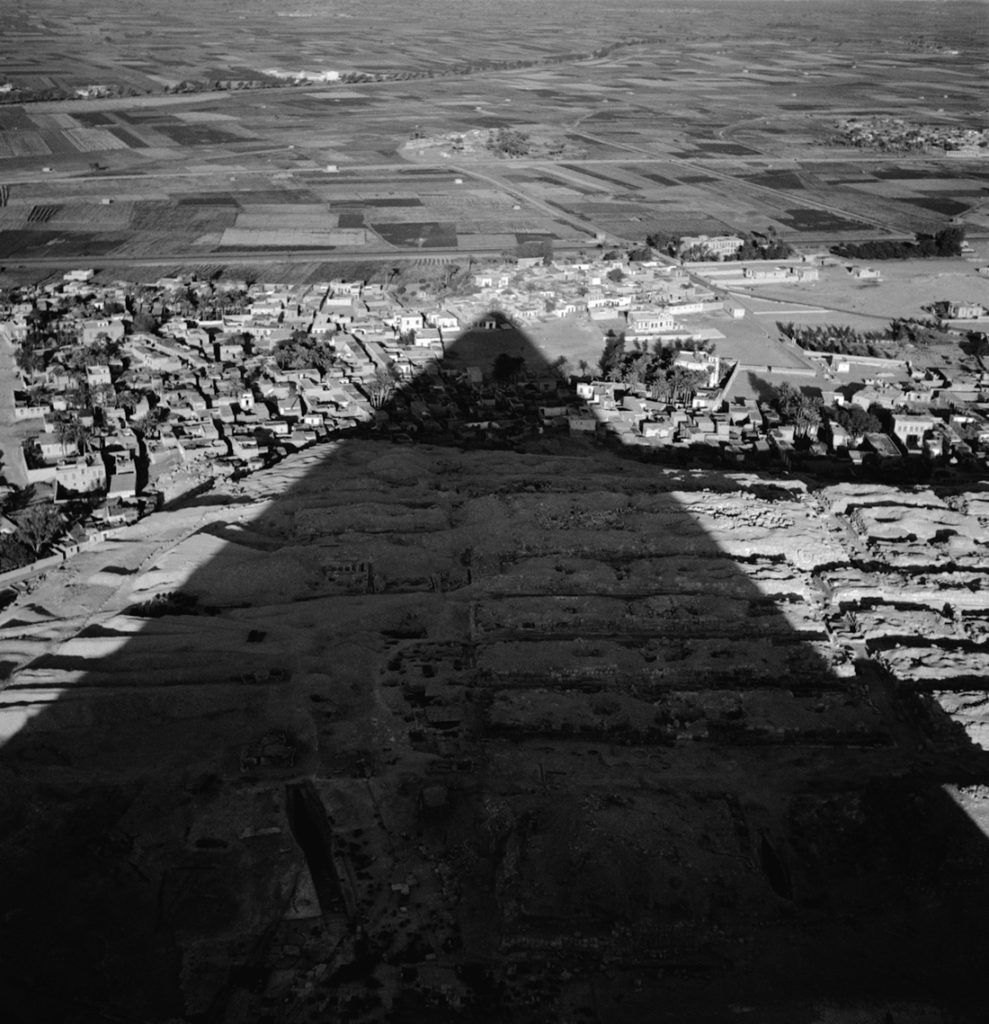

Allmer points out that Miller is present in the form of a shadow in many works from this period—in a photograph of Deir el Soriani Monastery in Egypt about 1936; in one taken from the top of the Great Pyramid of Giza about 1937 (a shadow within a shadow); in the image of Eileen Agar looking pregnant with her camera at Brighton Pavilion in 1937. The shadow is a supremely Surrealist motif, “simply an effect,” Allmer writes, “always in flux.” Or, as the writer Pierre Mac Orlan put it in 1930, with reference to Eugène Atget’s Paris scenes, “Photography makes use of light to study shadow. It is a solar art in the service of night.” Solarization would also be one of Miller’s great contributions to Surrealist photography—it was Miller and Man Ray who discovered what could happen if the lights were suddenly turned on during the development process: the tones reverse, and a ghostly outline forms. Man Ray would create a solarized portrait of Miller in profile, appearing like an electrified angel.

Allmer considers this interest in the shadow, and a willingness to include herself in the image, an important part of the ethical charge of Miller’s work: “Perhaps, if you’re a photographer, and you are there in these really traumatic situations, you are part of this story and not detached from it.” Miller’s involvement in world events was confirmed during World War II, a time when most of her Surrealist group (Breton and Man Ray among them) fled to the United States to escape the violence. (So much for Surrealism in the service of the revolution.) Miller, on the other hand, stuck it out in London, where she moved after Egypt to be with her second husband, Roland Penrose, surviving the Blitz and the constant threat of annihilation. She even put herself on the front lines of the U.S. invasion of Nazi-occupied Europe in 1944.

In Cocteau’s The Blood of a Poet, a title card declares that the poet composes “a realistic documentary of unreal events.” Miller’s work in the war strikes me as a Surrealist corollary to that statement, a surreal documentary of real events. In wartime London, Miller photographed the destruction caused by the Blitz. Her eye was trained to see the uncanny qualities in the fragments of the city she encountered; she out-surrealed the Surrealists.

“She finds the battered typewriter or the mannequin standing in the street corner or the window blown in such a way that the glass makes a pattern. She’s just constantly looking for the concretization of dreams,” Antony Penrose tells me. “That’s what she’s finding.” One such example is of a stone angel, fallen to the ground with her neck severed by a metal bar, a brick smashing her breast. Miller called it Revenge on Culture (1940). “Who is taking the revenge?” asks Caws, the author of Surrealism, when we speak. “She was taking her revenge on us for not knowing whose revenge it was or why . . . and which culture, of course. Everything about that particular image says to me that’s why she’s a Surrealist.” Miller’s wartime photographs would appear in a book called Grim Glory: Pictures of Britain Under Fire (1941), published so that U.S. audiences an ocean away from the conflict could appreciate the terrifying realities of life during the Blitz.

Although her accreditation did not permit her to report from combat zones, Miller found herself in Saint-Malo for the Allied offensive and, staying on with the infantry, was among the first people let into Dachau and Buchenwald after they were liberated. The image of Miller in Hitler’s bathtub is well known (taken in collaboration with David E. Scherman), but the photographs that she made as the concentration camps were liberated are among the most haunting and disturbing documents of the war.

All photographs © Lee Miller Archives, England

Suffering from alcoholism and probably post-traumatic stress disorder after her return home, Miller lost the desire to keep taking photographs. Production eventually slowed to such a point that her son didn’t realize the “extent” of what she had made, the “depth and penetration” of her wartime work.

Miller, who in 1966 became Lady Penrose when Roland was knighted for his services to art, threw herself instead into cooking, training at Le Cordon Bleu London and taking great pride in whipping up the most original, surreal dishes she could: Her son remembers being served blue spaghetti and pink breasts made of cauliflower with cherry tomatoes for nipples. Her recipe for chicken was prepared with so many herbs it turned green. Miller’s cooking is often underappreciated as an important continuation of her Surrealist work—it’s domestic, it’s fleeting, and it’s not war photography, after all. But it was just as much about unsettling people’s received ideas about how the world should be. A Surrealist from beginning to end.

![Lee Miller,[Mirror Series] Lee Miller,[Mirror Series]](https://aperture.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/247MAG049_Miller-HR.jpg)