How Pictures Can Shape an Essential History of Queer Life

From photographs of same-sex weddings to HIV/AIDS caretakers, Stephen Vider’s new book shows how queer people redefined gender roles, domestic space, and the politics of intimacy in the twentieth century.

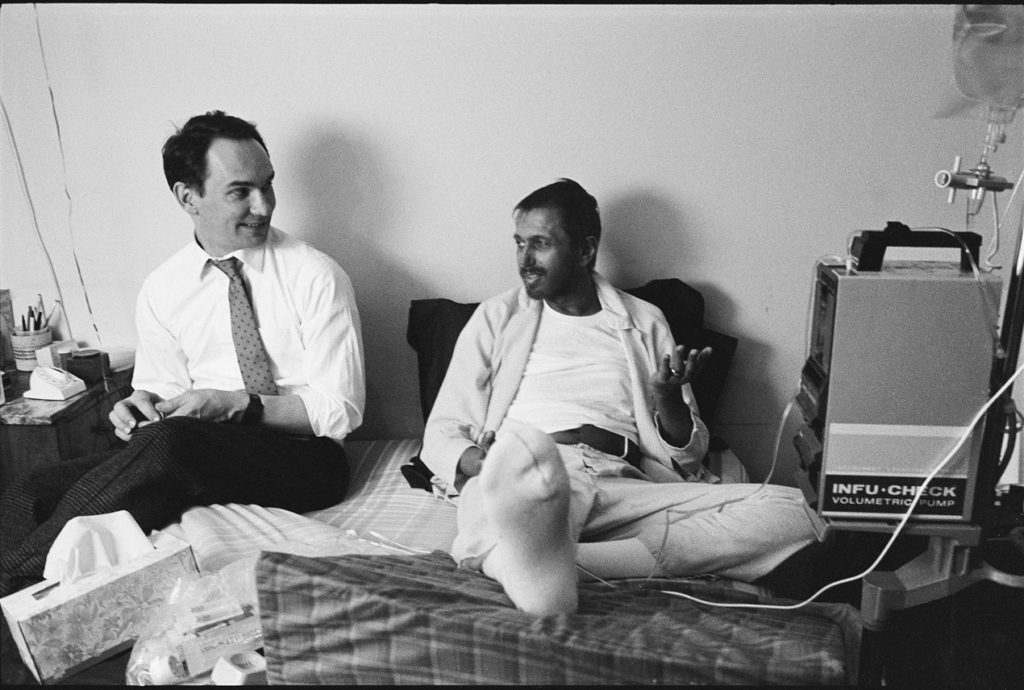

Susan Kuklin, Kachin and Michael at Michael’s Apartment, 1987

Courtesy of the artist

“There’s no place like home,” Dorothy famously chanted. Queer people find themselves still under that spell, wrapped in its ambivalent multivalence: longing for a safe space of our own, relieved to leave childhood trauma behind, settled into the uncertainty of our place in the world. “They say that home is where the heart is,” mourned troubadour of the demimonde Marc Almond, “but home is only where the hurt is.”

Curator and historian Stephen Vider seeks to complicate all that in his new book The Queerness of Home: Gender, Sexuality, and the Politics of Domesticity after World War II. The work assembles material records and cultural meanings of “home”: from pictures of weddings and other domestic/clandestine gatherings in the 1950s, through 1965’s blockbuster, camp culinary guide The Gay Cookbook; from lesbian feminist architect Phyllis Birkby’s 1970s multiple relationship “domes,” to contemporary queer and trans elder housing. Vider recently Zoomed from his own home to discuss with Jesse Dorris how the work of Samuel Steward, Susan Kuklin, Bruce Pavlow, and countless anonymous others should broaden our understanding of what homemaking looks like.

Human Sexuality Collection, Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library

Jesse Dorris: What is the origin story of this book?

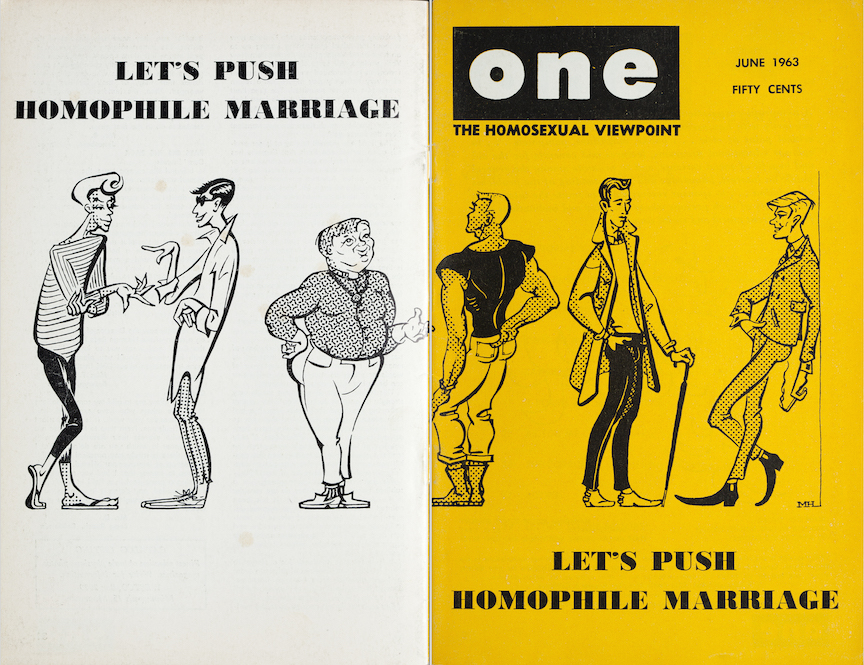

Stephen Vider: It was at a moment when the same-sex marriage cases were beginning to make their way through the courts. A lot of the critiques were that same-sex marriage was going to be a kind of normalizing project that was going to strip queer culture of everything that made it different. What intrigued me was the ways that domesticity, or home, seemed to be made synonymous with marriage—which meant that “home” was a normalizing project. And I got interested in thinking about the ways that queer people had, in fact, used home spaces in ways that challenged gender and sexual norms. We are always in the practice of opening our homes to other people. Feminist scholars have pointed to the labor of home; we should think about that as part of a political project also. And so, home is a kind of portal to public life. If we disentangled home from marriage, what else would we see?

Courtesy of ONE Archives at the USC Libraries

Dorris: Home can be protection from the state. But it can also be a site of the state’s power. Queer people have always been present in the creation of these spaces: the interior decorator, the butch handyperson—they’re acting as boundaries for what heteronormative homes look like. They pose a threat. But there’s the idea that gay men began to decorate as a way to assert themselves in the home, to convince people their presence is valuable.

Vider: One starting point for the stereotype is a 1917 piece Dorothy Parker wrote for Vogue, about a fictional decorator named Alistair St. Cloud. Everywhere you look in this house he decorated, there were tassels. Off of the curtains, off of the furniture. And he’s also wearing a robe with tassels coming off of it. So there’s a way that his queer body inhabits this space. In the 1940s and ’50s, this image of the gay decorator really takes off. It’s partly this idea of an alignment of gay men, especially, with a kind of expert taste—only as a visitor, someone who’s creating all the conditions for the heterosexual home and then going to depart it. And who knows where he goes after that, because he often doesn’t seem to have a home of his own. There’s also a profound anxiety about gay men corrupting the home.

Courtesy the artist

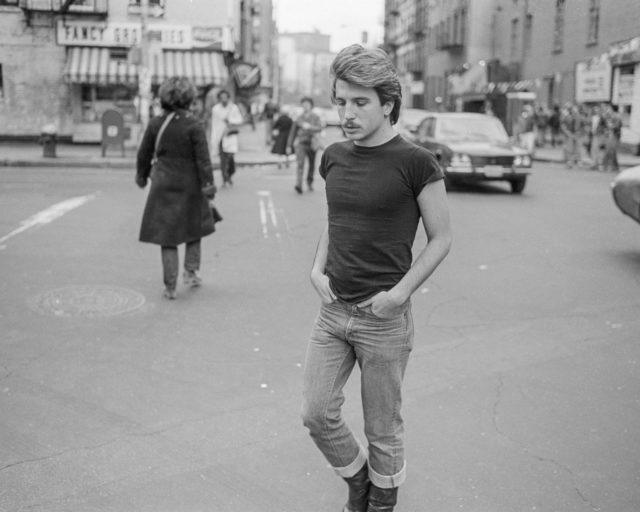

Dorris: Meanwhile, some forms of photography require a private space, an actual darkroom, a home or space of your own. Artists like Samuel Steward and James Bidgood made their homes projection screens of their own fantasies.

Vider: Well, George Platt Lynes developed his own photography. But Steward is using Polaroids, and so he doesn’t have to worry about going to a drugstore to have them developed. There’s a photo of his in the book where he has one of his lovers sitting on his Murphy bed, and behind him are these drawings he had painted of two men, naked, smoking. There’s a strange kind of mirroring, of fantasy becoming reality and then fantasy again, in the frame of the photograph. There’s a quote I love from anthropologist Mary Douglas, “The home is the realization of ideas”—home is the process of making a fantasy real. And that complicates our ideas about gay men in the ’50s: we think of a lot of sex happening in public—in bathrooms, in parks. But what happens when you pick someone up and bring them back to your apartment? What happens in that space, after?

Dorris: And how to hold onto the memories.

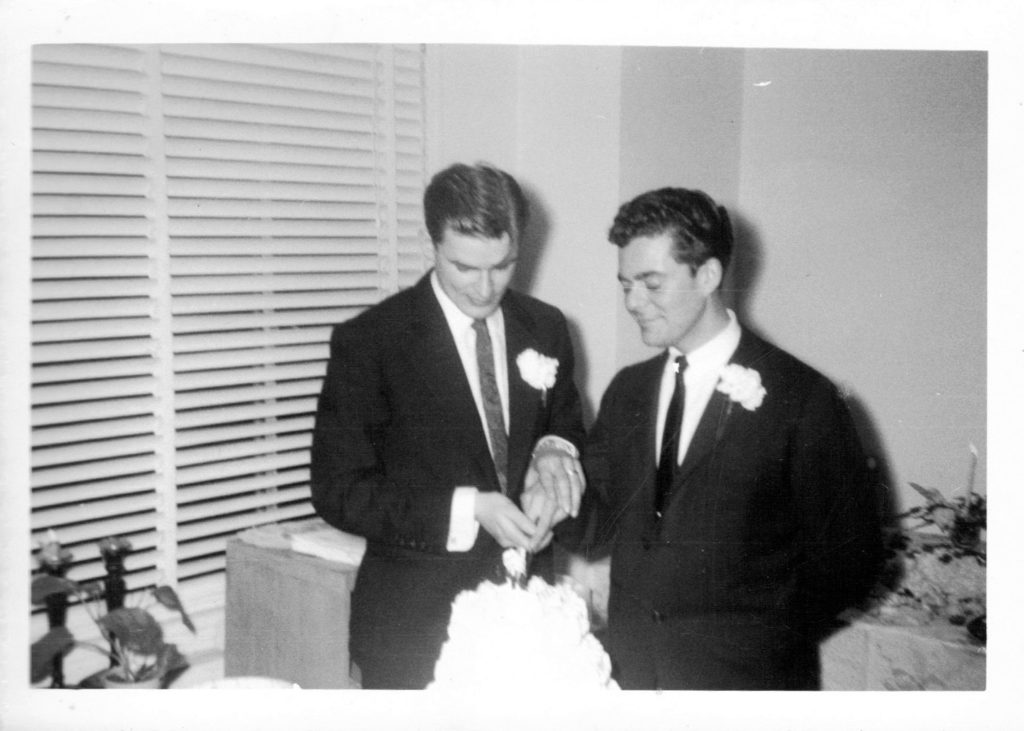

Vider: There’s a series of photographs in the book of a gay wedding in Philadelphia around 1953. There’s cutting the cake, there’s doing the ceremony, there’s kissing after the ceremony, there’s dancing. It looks like any other wedding album. We know what the poses are supposed to be. And they perform them. The difference is that this is happening at home, because it can’t happen in public. And so that raises, again, the larger question about what it is that home made possible.

Courtesy the ONE Archives at the USC Libraries

Dorris: There’s a tenderness and sadness in thinking about these gay designers telling women how to organize their houses, their living rooms, with a wedding photograph in a lovely frame in pride of place over the mantel or whatever.

Vider: In places like Casa Susanna, the mid-century retreat in the Catskills for trans women, taking photographs was really important. This was a space where people could go and be themselves, express themselves as they wanted to, as they felt, without fear. Photographs were part of preserving that, but also mirroring it back. To take a photograph of a moment is to affirm it.

Dorris: These photographs must have been so treasured. But also, perhaps, hidden. Because they’re evidence of their subjects’ existence, but also of the kind of gender crimes the people in them are committing. Their existence creates danger.

Vider: The early trans leader Virginia Prince, who published the magazine Transvestia, wrote about her first time at Casa Susanna. Going to the house was a way of having life the way you always wanted it to be. If home is about the realization of ideas, photographs help hold onto those ideas and that reality, even as time is passing, and even when that life isn’t always possible.

Collection of the Art Gallery of Ontario

Dorris: Home was also the place where one could receive Transvestia. Which gets to this idea of privacy. We’re at this extraordinary moment where we have this infinite and encouraged ability to represent ourselves, to represent our homes, mediated through companies who make money off it. At the same time, the US Supreme Court is poised, in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, to more or less overturn Roe, and thus, let’s say, complicate our current idea that we have a right to privacy within our own bodies. And, so many of us have been stuck in our homes for so long, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Vider: Even though privacy is often thought about as a right, the way that home actually mediates privacy is always a kind of privilege.

Courtesy Juanita Szczepanski, Jean Carlomusto, and GMHC

Dorris: The right to privacy might be a right, but the right to a home has never been established.

Vider: In the book, I write about attempts to set up the earliest group homes and shelters for queer and transgender youth in the 1970s. What does it mean when privacy at home cannot be taken for granted? What does it mean to try to create that space for people whose lives are very precarious? It is a particular class of queer people who are able to take their privacy for granted. The link between privacy and home really becomes clear in the case of unhoused youth. These group homes, they are not private: there are a lot of people coming in and out. They’re being talked about in funding reports. They’re being photographed. It’s a mediated privacy.

But also, home can be isolating. For people living with AIDS in the 1980s and ’90s, home became a space that could keep them invisible. It reinforces silence and shame and stigma when people are too sick to go and do grocery shopping for themselves. How do we think of who is reaching into these spaces, volunteers going into these spaces to care for people? If you think of home as simply private, you can miss those stories. If you think of home as porous, you start to think about it as a space of connection, people making connections across different types of racial or gender or sexual difference in ways that are meaningful and powerful.

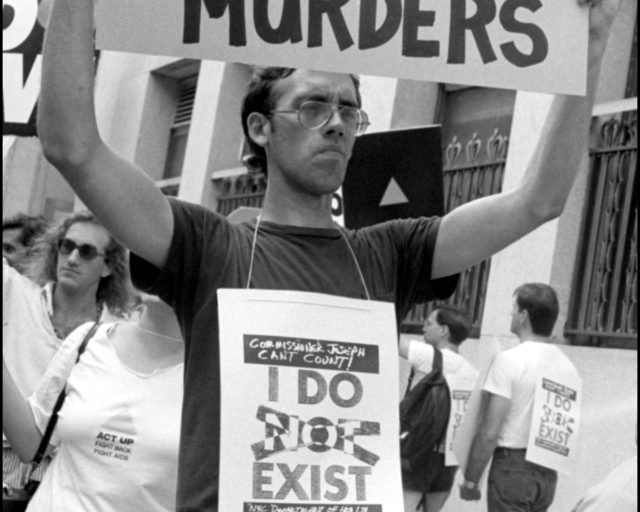

Dorris: It’s also a space in which technology comes through and changes. For Samuel Steward, and for the makers of documentaries you write about including the TV series Living with AIDS (1987), their work was possible because of a relative democratization of the machinery. Home is a site of creation.

Vider: There was a recognition by artists and activists that the ways HIV and AIDS were playing out in people’s home lives actually needed to be made more public. Because to make everyday home life with illness more public is to destigmatize it and restore humanity to people who are often disavowed by the culture at large. A photograph that’s really been important to me is one by Susan Kuklin of the Gay Men’s Health Crisis volunteer Kachin Fry and Michael, her buddy or client, as GMHC would have called him.

Courtesy of the artist

Dorris: How did you come across this photograph?

Vider: I was curating an exhibition called AIDS at Home for the Museum of the City of New York, doing research on GMHC’s Buddy Program. And I stumbled on Kuklin’s book, Fighting Back: What Some People Are Doing about AIDS (1989), for which she had followed a Buddy team in the East Village for a year to create this mixture of photographs and writing. I spent a lot of time talking to her about her photographs. There’s so much happening in this one. First, there’s this surface level of a kind of unlikely pairing of people. Then, Michael is wearing a T-shirt with the “Silence=Death” emblem, and the photo is from 1987, just as that emblem is being introduced as activism. So the photo is raising questions about what happens when activists go home. The photograph itself is a form of activism.

Courtesy the artist

Dorris: The caregiving is activism.

Vider: And we don’t always think of caregiving that way. Susan captures their emotional intimacy so well, but also their physical intimacy. It’s really important to remember that this is a moment when people had a lot of misconceptions about how HIV was transmitted. The idea of somebody coming into your home, lying on your bed and talking with you—it’s really powerful.

Courtesy of the artist

Dorris: There’s another photo I can’t stop thinking of, by Bruce Pavlow of a resident at the group home Survival House in 1977. What was the background here?

Vider: Pavlow self-published a book of the photographs he had taken as part of a class at Berkeley, where he was an undergraduate—and this would have been very new for 1977, a class on gay space. This is a moment where there’s so much growing of queer commercial space; this is the moment of Harvey Milk. The fact that Bruce thought to go to a queer group home is really fascinating in itself. He also created a two-hour documentary film about Survival House with all of his interviews, which we’ve worked together to preserve and digitize. But the photographs convey a sense of the range of people who were living in Survival House. The photo on the cover of the book is of the group of residents playing Monopoly. It has this sweetness of playing a board game, which we think of as so much of a family activity, to claim their household as a new kind of queer family. And then there’s the irony that Monopoly is a game that’s entirely about buying property being played by a group of unhoused youth.

The photo you pointed out is of one of the unnamed residents, who’s not interviewed in the film. There’s something really classic about the pose in the photograph, and of this floral armchair taking up the full frame. The curtain behind her, the cup of coffee next her. And the way that she inhabits the space, looking off. It conveys a kind of privacy, a boundary about how much we can know.

Courtesy the artist

Dorris: Because we don’t know the story, we project all kinds of things over the image. I don’t know the subject’s pronouns, I don’t know if they consented to having the photograph taken, and I don’t know the stakes of the photograph’s existence. As we were talking about life at Casa Susanna, this is proof that a certain life was being lived in a certain way. And that proof can be weaponized, right?

Vider: Survival House closes in 1978 because they can’t maintain the funding. But other queer and trans group homes for unhoused youth come after. The Buddy Program continues from 1982 into the early 2000s. So I guess I’m looking at moments of emergence. By the Clinton years, home was starting to be political in a new way, when you saw domestic-partnership legislation and the early debates around same-sex marriage. Domesticity takes on a different meaning once you start really seeking legal recognition of queer couples and families. And now, there are these new group homes for queer and trans elders. That’s striking, because it seems like another iteration of the way queer people use home: recognizing the importance of having an affirming home and its precarity.

Dorris: Home has changed again, as a result of COVID.

Vider: There was a sense, at the beginning of the COVID pandemic, that people felt driven to preserve the moment, because it felt so exceptional. COVID archives emerged very quickly, and those are archives of domestic life. And I’m thinking of all those moments of people clapping for health care workers, which was a profoundly public moment of people in their private spaces performing together. That challenges what home is.

Courtesy the Rainbow History Project

Dorris: And we see it all instantly. Whereas there’s much less information around queer pasts. It’s meaningful to see that, yes, these people lived, and their homes looked very different than ours, and just like ours. There’s a continuity and a difference.

Vider: What I hope the book shows is a method for thinking about everyday life. The photographs give us emotional access in ways other types of material culture don’t, because they are representations of moments, but also because a lot of care goes into taking a photograph. A lot of care went into making the decision to take a photograph. When you see one of someone’s home life, you see a desire to preserve that moment. They make real to us a moment in space and time. But they’re also a kind of willed testimony of people in the past who wanted this story to be preserved. Maybe they didn’t imagine it being preserved for us.

Dorris: But they saw themselves as valuable in a way that’s deeply moving. It’s maybe easy to take it for granted, like taking privacy for granted. But the proof that they saw themselves as valuable enough to make these little monuments to themselves is deeply moving.

Vider: And there’s a tension in them. Some of it’s moving, some of it’s challenging. And that’s why it’s powerful.

The Queerness of Home: Gender, Sexuality, and the Politics of Domesticity after World War II was published by the University of Chicago Press in December 2021.