Steven Meisel, Lucy Ferry, Brookville, New York, for Vogue Paris, November 19, 1993

High-end fashion photography toward the end of the 1980s reveled in bravado. Think of the swagger of Herb Ritts and Bruce Weber, or the aristocratic eroticism of Helmut Newton. But by the early 1990s, young British photographers such as Glen Luchford, David Sims, Craig McDean, and Corinne Day arrived to rejuvenate the field, encouraged by a new community of magazines from the United Kingdom, especially iD and The Face. This renaissance disrupted the haute isolation of fashion photography, and cultural themes, street style, pop music, and club life became the fabric of new imagery. Fashion’s aspirational glamour was challenged by a personal narrative of the young.

As always, in this moment, the American photographer Steven Meisel assimilated shifts in both fashion and its photography to push the conversation. The year 1993—which saw the election of a young Bill Clinton, the first bombing of the World Trade Center, and the debut of television series like The X-Files and Beavis and Butt-Head—was also a year of prodigious output by Meisel. The exhibition Steven Meisel 1993: A Year in Photographs gathers images culled from that year alone, featuring twenty-eight international Vogue covers and more than one hundred editorial stories. This is the second exhibition of fashion photography staged at the MOP Foundation (an acronym for Marta Ortega Pérez, daughter of the founder of Zara) in A Coruña, Galicia, on the northwest coast of Spain, a remote location, far from the obvious hubs of international fashion.

In a career spanning forty years, Meisel has defined the creative potential of fashion photography and has been held in consistent esteem in a traditionally mercurial arena. He moves quickly, and has shuffled through inexhaustible references to performance, nineteenth-century painting, surveillance imagery, pornography, and narrative gesture to make work that is inventive and unpredictable, revitalizing fashion history and anticipating its future. For four decades, the work has been an act of daring and dazzle and shrewd connoisseurship. Together with Guy Bourdin, Tim Walker, Nick Knight, and Steven Klein, Meisel developed fashion photography as a complex narrative in conversation with cultural preoccupations.

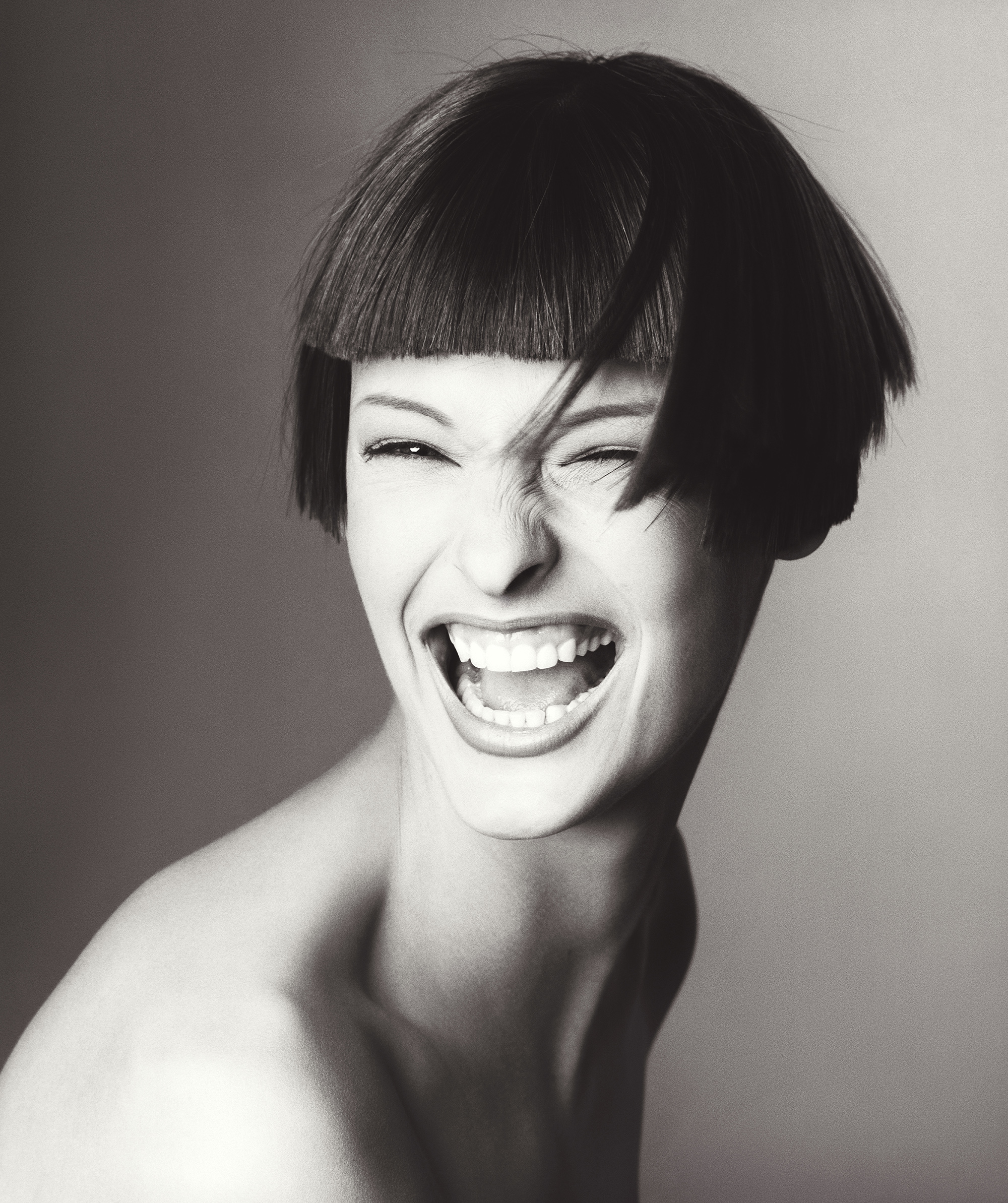

By isolating one pivotal year, the exhibition extracts a passage from a longer creative arc, and challenges the framework of a conventional career retrospective. Meisel emerges as a portrait photographer of great sensitivity. Fashion photography, like cinema, is a collaborative effort, and Meisel has been credited with cultivating a group of models in the eighties (Naomi! Linda! Christy! Amber!) whose presence and charisma elevated the profession. Although all fashion photography relies on the character and role-playing of those in front of the lens to suggest narrative and mood, Meisel’s work from 1993 goes further in its emphasis on the person as much as on the garments.

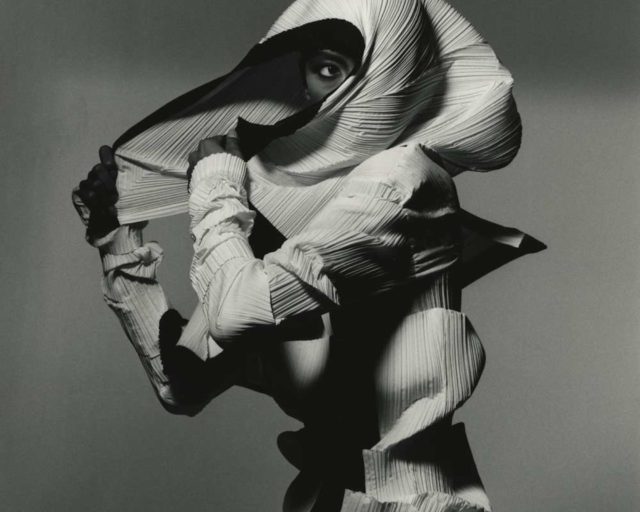

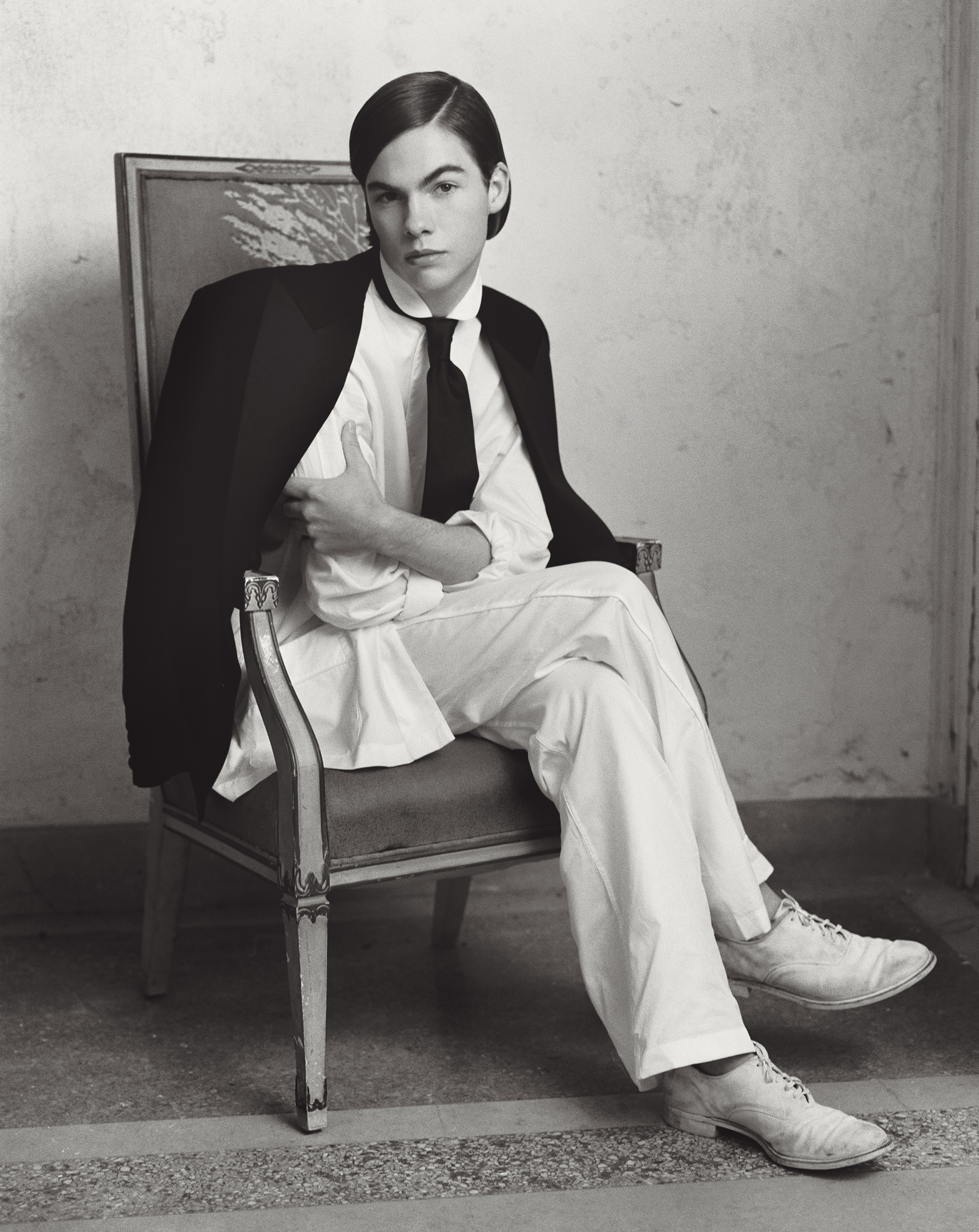

Here, the totemic Linda Evangelista poses for Vogue Italia in conventional portrait head-and-shoulders format, all the more appropriate to frame her merriment; later that year, we see Stella Tennant (Vogue Italia again) with no noticeable couture, but with an expression of guarded unkindness. Kristen McMenamy perches nude, with the exception of an elaborate headpiece, in the rosy opulence of the Ritz in Paris; a young Marlon Richards appears with a cluster of stylish companions (in a photo somewhat reminiscent of his father’s Rolling Stones Between the Buttons album cover); and a grungy Axel appears in a snapshot for Per Lui.

By isolating one pivotal year, the exhibition extracts a passage from a longer creative arc, and challenges the framework of a conventional career retrospective.

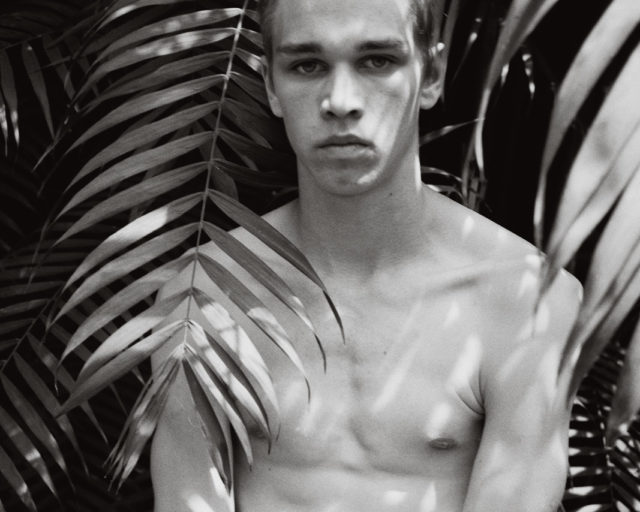

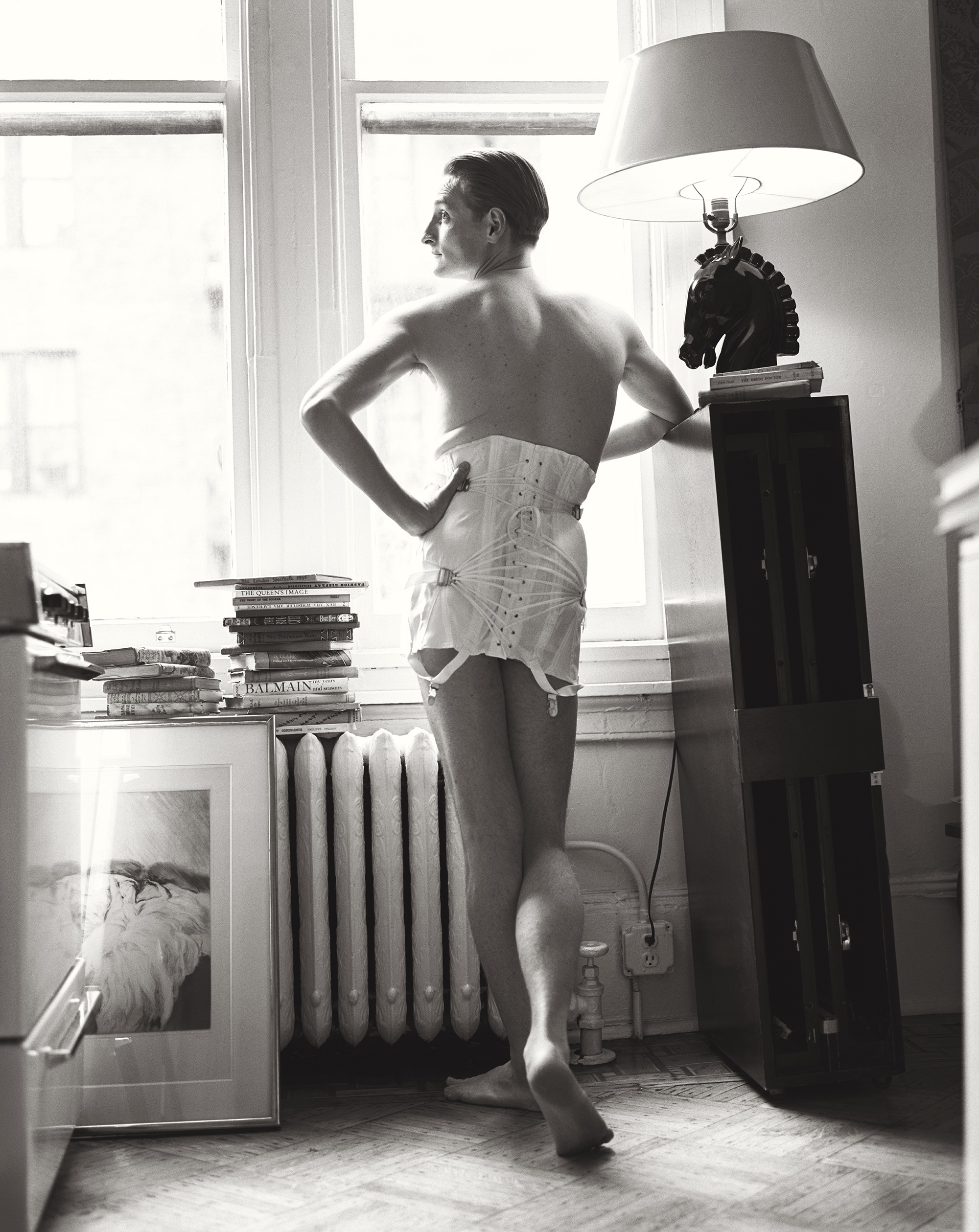

The dominance of black and white supports Meisel’s classicism, and an authenticity—not an idea often associated with fashion—that sidelines artifice. Here, glamour resides in the elegance of individual gesture and body language, the geometry of the frame containing the animation of the figures. Models huddle, stroll, and stride; they drape, their hands flutter unexpectedly, legs akimbo. In a time when men were idealized in fashion as chiseled and aggressive—Mark Wahlberg grabbing his crotch for the camera—the boys here are lithe and gangly, rattling constructions of gender, as in the photographs of Hamish Bowles clinched in lingerie. Much of the work feels improvisational, an impression of play, pleasure, and often mischief, deflating pretension and self-importance.

All photographs courtesy Steven Meisel Studio

Meisel has at times aroused controversy. He has periodically touched upon social questions, racism, addiction, cultural narcissism, and often satirized fashion’s own mannerisms and exhibitionism. “Makeover Madness,” an editorial that occupied eighty pages of Vogue Italia in 2002, casts a narrative of models submitting themselves to all forms of body intervention, gowned in couture but swaddled in gauze. These excursions into social commentary showcased Meisel’s consummate engagement with what might be possible in a fashion photograph.

Meisel maintains the aura of someone who is so private as to be enigmatic. Despite his renown, he rarely gives interviews, and he has never published any of the expected survey books of his work. The news of an exhibition of Steven Meisel is, for the fashion and photography community, an occasion of celebration and curiosity. This selection from 1993 represents how he maintained autonomy from the bandwagon of the moment to reveal how the best fashion photography might honor our collective aspiration for connection and joy.

Steven Meisel 1993: A Year in Photographs is on view at the MOP Foundation in A Coruña, Galicia, Spain, through May 1, 2023.