Charlie Engman, Office Chair III, 2023

Earlier this year, when I asked the photographer Laurie Simmons why she started using artificial intelligence as a creative tool, she said: “Because it exists!” Simmons’s initial interest in AI emerged as the COVID-19 pandemic limited excursions or gatherings for photo shoots, and she has recently used DALL-E, a popular text-to-image generator launched in 2021, to make new work. Amid debates about copyright and originality that AI sparked throughout 2022, she’s among a growing number of photographers exploring the potential and problems inherent in the technology.

Many concerns around AI and photography stem from the lack of structure or accountability for image-to-text generators, which scrape the internet for billions of images with associated text—captions, tags, and so on—to feed their databases. A group of artists recently filed a class-action suit against Stability AI for copyright infringement, as has the stock photography service Getty Images. Anxiety about the death of art seems to accompany contemporary art with every new development, even as artists adopt and adapt new tools in their practice. Simmons recently featured some of her new work in the online collection In and Around the House II, organized by the Web3 platform Fellowship.

In many ways, AI is too broad a term, encompassing everything from self-driving cars to email phrasing prompts to personalized medical recommendations. It’s supporting your Google searches as well as the object-selection tool in Photoshop. For many artists, AI has meant a radical expansion of possibilities, but the technology also foreshadows the automation of much creative labor. People worry about their jobs.

Artists were initially intrigued by an early form of AI known as GANs, or generative adversarial networks, which created composite visuals from existing data, including images. GANs allow artists to compile personalized data sets; for instance, photographers may use their own archive of images to create novel work. In contrast, text-to-image generators depend on massive data sets that no single artist can compile. Until recently, they also needed invitations from developers to access these generators. But, by 2022, with the proliferation of the technology, a growing number of artists began sharing their experiments, and people saw firsthand what these systems could create from a simple string of words.

Simmons compares the experience of using DALL-E to watching an analog photograph appear in the developer solution. Almost immediately, the artist was able to make images that reproduce the domestic and psychological interiority for which her work is known, including doll-like figures in familial settings, extending the feminist discourse pervasive in her practice. Even when her AI figures are outdoors—strolling in fields or sitting on patios—her compositions suggest vignettes, creating a sense of the figures being contained or constrained by objects and environments. One “self-portrait” depicts a woman walking a dog along a country lane, and bears a startling resemblance to Simmons, her own dog, and even the roads near her home.

Shortly after her early encounters with DALL-E, she became more deliberate about her process and began identifying features and attributes to carefully construct more accurate and effective text prompts. For Simmons, these prompts feel like secrets—at least for now—and also full of surprises. “Some days I feel like an AI whisperer, other days like a flop,” she says.

Our physical gestures are expressive of internal, psychological states, but AI struggles to process the aesthetic of emotions.

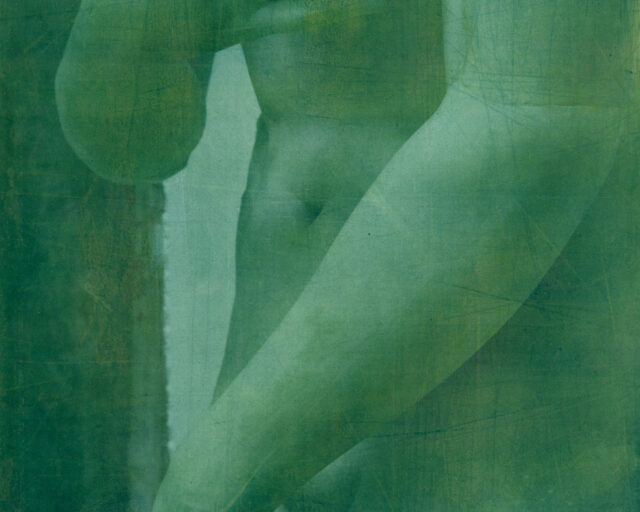

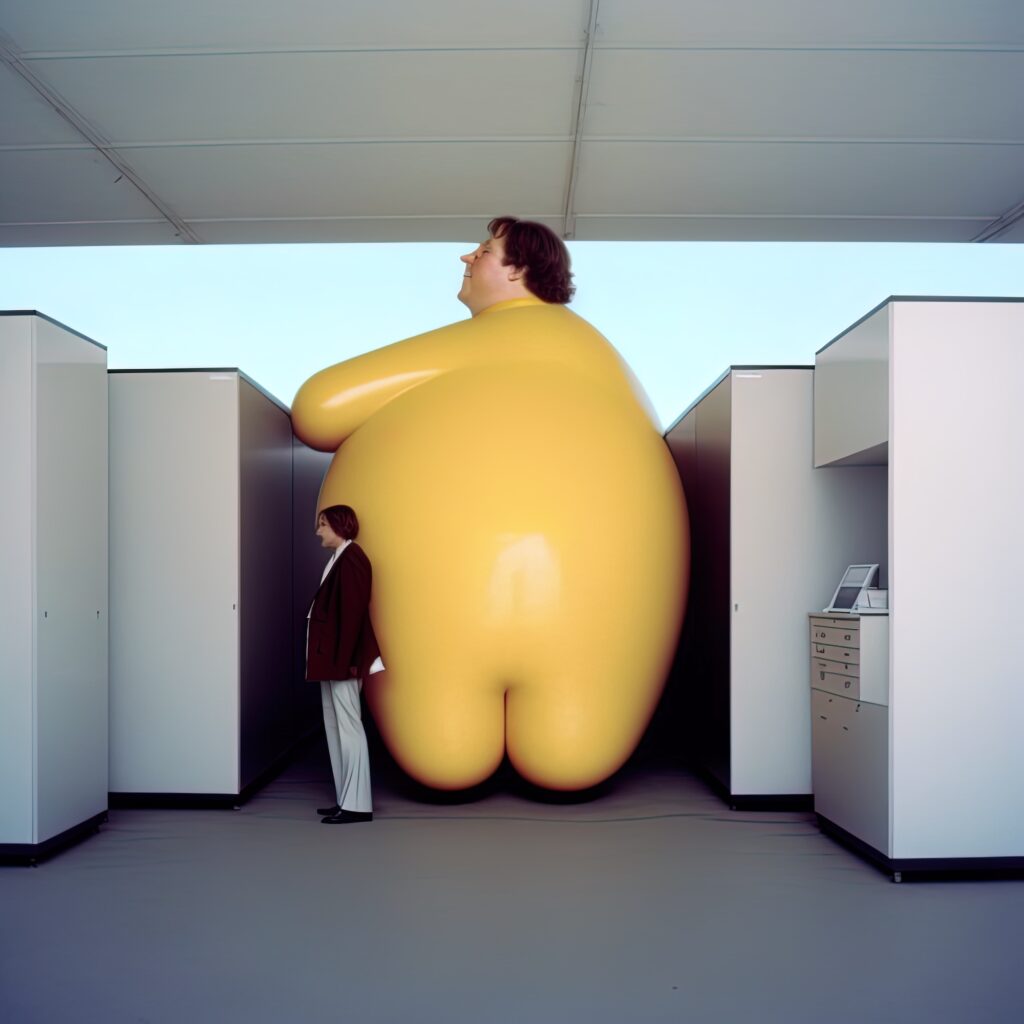

Due to the range of sources from which these image generators pull data—online images ranging from stock photography, news imagery, social media posts, and personal websites—the results can range from the real to the uncanny. New York–based photographer Charlie Engman believes that AI’s limited understanding of bodies stems from perceiving them through images, not lived experiences. Informed by a background in dance and performance, Engman’s work spans fashion imagery as well as collaborative portraits of his mother. His AI experiments push some of these ideas further, exploring how the technology is able and unable to articulate bodily movement.

Our physical gestures are expressive of internal, psychological states, but AI struggles to process the aesthetic of emotions. Grief or pleasure may appear on AI-generated faces but isn’t replicated in those figures’ postures or gestures. Engman has observed that the body language of performers includes subtle movement choices cultivated over time to express thoughts and feelings, but these are rarely read accurately across AI data sets. Tags associated with images don’t typically specify a relationship between affect and a particular gesture. For instance, an emotion might be determined as happy because many images with smiles are tagged “happy,” but the AI might not be prompted to discern other subtle postures or stances, such as relaxed shoulders. For Engman, this gap is a compelling reason to explore the technology.

The works he’s made using Midjourney, another text-to-image generator, depict strange and impossible contortions, many that bend the laws of physics and physical proximity. He’s been able to use the tool to create situations that he would never request of a subject, for ethical reasons as well as physiological limitations. His images of bodies merged into chairs, for example, playfully satirize modern office life. Other experiments have yielded images that mimic the visual language of fashion spreads, with his version featuring elongated models that appear both familiar and unnatural. Anyone interested in making images “must be curious at the very least,” Engman says.

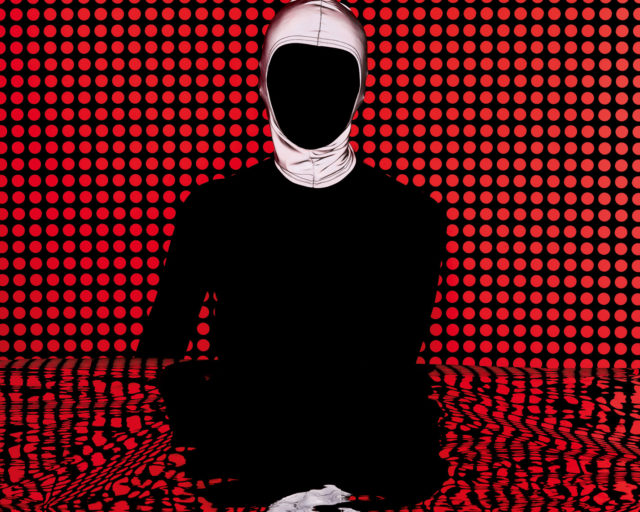

When DALL-E and Midjourney became widely available, many were also curious about how these data sets might interpret various identities and lifestyles. The interdisciplinary artist and researcher Minne Atairu developed an interest in AI in 2020, as part of her ongoing examination of creative technologies as a PhD student at Columbia University. Atairu’s work has primarily focused on the ways that technologies can reproduce or alter absences in cultural histories, particularly those of postcolonial Nigeria.

Initially, she trained a GAN data set to produce portraits based on images of Black models she downloaded from Instagram. When she turned to Midjourney, she discovered that the system’s ability to image Black identity produced recurring stereotypes, despite her efforts to push past them. Typing specific descriptions into the generator—such as a lime-green color for clothing—produced an image of a Black person in a cityscape with details she found remarkably similar to those of her neighborhood in Harlem. After some trial and error, Atairu inferred that Midjourney presumes a set of socioeconomic conditions by associating bright colors and Blackness.

Like the data sets that form them, these systems are not neutral. Midjourney’s limitations further spurred Atairu’s investigation into how text-to-image generators depict certain features on a Black person. Her series Blonde Braids (2023–ongoing) tackles this problem and the corrective work required. Requesting “blonde” hair as a part of her text prompt generated a suburban, middle-class environment, reproducing broad cultural stereotypes that reinforce racist imaginaries. The generators likely also struggled due to limited information in the data sets about people. Atairu explained how Melanesians—the Indigenous inhabitants of Fiji, Indonesia, and Papua New Guinea—have naturally light hair, but the generator’s struggle to depict this suggested that it was unfamiliar with this identity. When she requested to prompt to generate an image of two people and specified melanin tones, the request for blonde hair would appear on both figures, but the generator seemed incapable of making them the same skin tone; one was always lighter than the other.

“Coded biases and stereotypes cannot be eradicated by tweaking text prompts and curated selections,” she says. “Instead, to address such inference problems, the developers need to review the underlying data structures used for training the model.” Atairu’s photographs may not represent actual people, but they reflect a significant and enduring information bias. “No matter how hyperrealistic,” she adds, “there will always be a glitch.”

All photographs courtesy the artists

These are still early days, and many feel this is a special, even fragile, time for AI-generated imagery. To discredit these representations based on image quality or veracity alone is to miss the larger point about the inequality of the culture from which they emerge—both in terms of social mores and online data. Experimenting with these systems is a first step toward demanding they be made better and more inclusive. While Engman and Simmons push their work in new aesthetic directions, Atairu alerts us of the assumptions and imbalances that underlie AI databases.

AI may have already begun radically altering how we think about photography, but it’s helpful to remember that such discussions have always been a part of the medium’s evolution. Older arguments around authorship and creativity will reappear in this new context, and artists who consider the aesthetics and ethics of images are right to demand more conscientiously collected data. As AI’s relationship to photography continues to be defined, it will nonetheless be shaped by the artists exploring the technology’s limits in playful, inventive, and critical ways.