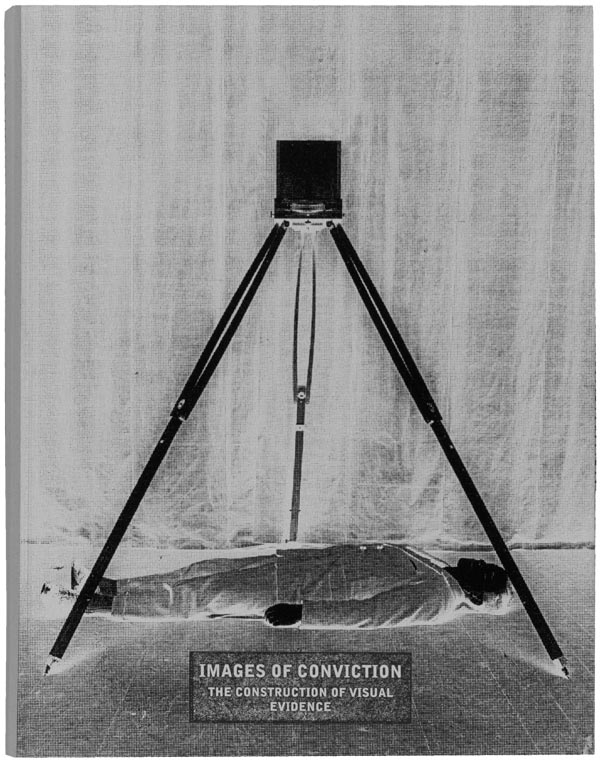

Images of Conviction: A Conversation with Diane Dufour and Xavier Barral

Through eleven case studies from Alphonse Bertillon’s Parisian crime scenes to aerial views of drone strikes in Afghanistan, Images of Conviction: The Construction of Visual Evidence probes one of the central impulses in photography: portraying the truth. Aperture recently spoke with Diane Dufour, director of Le BAL, where the exhibition Images of Conviction was presented in Paris last year, and Xavier Barral, publisher of the catalogue, about their collaboration and the enduring fascination with forensic photography. —The Editors

Images of Conviction: The Construction of Visual Evidence (Paris: Éditions Xavier Barral, 2015)

Aperture: Images of Conviction, winner of the Photography Catalogue of the Year at the 2015 Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards, examines the power of photography in representing crime, war, and acts of violence. What was the origin of this exhibition? At an institution more commonly known for presenting contemporary photography, how has the exhibition enriched your program at Le BAL?

Diane Dufour: Our mission at Le BAL is to think about the role of images in society as well as in our understanding of history. Too often the status of the image oscillates between those who believe the immediate reality represented by the image and those who consistently challenge the validity of the image as too fragmented, too subjective, too manipulated. In Images of Conviction, we wanted to examine how experts or historians investigating crimes of violence must build a case in which the image “becomes” a form of evidence. Photography can document a scene of action and return a set of visible results—but what can we really learn from what we see in a picture?

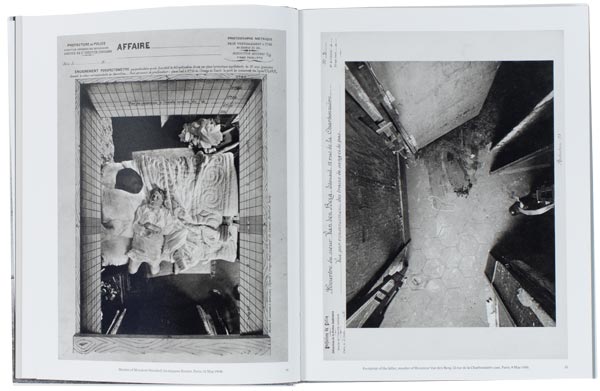

Spread from Images of Conviction, including murder scene images by Alphonse Bertillon, Préfecture de Police de Paris, 1908 and 1916

Aperture: The catalogue contains case studies that took place in such varied locations as France and Kurdistan and span more than a century. How did you select these studies? Were there others you would have liked to explore if you had more space in the exhibition and catalogue?

Dufour: Over the course of three years, we identified eleven historical and contemporary cases. We persuaded museums, foundations, collectors, and photographers to offer us images, and we then invited an expert to decipher each case for the public at Le BAL.

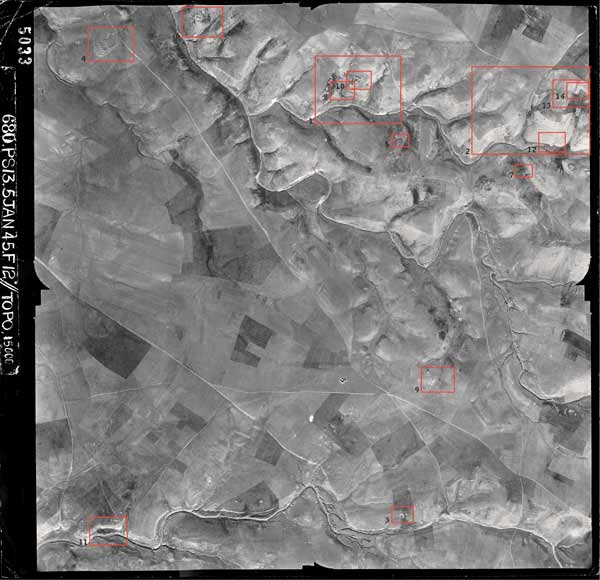

In the eleven cases, the device of presentation for the book and exhibition—mounting, assembly, expansion, accumulation—reveals at the same time the gesture of the criminal and the investigation of the expert. Criminologist Alphonse Bertillon built the metric space of the scene; forensic scientist Richard Helmer superimposed images of the skull and face of Josef Mengele; the book of the destruction of Gaza is an inventory of the buildings destroyed after the Israeli attacks there in 2009. Sometimes it’s the very material of the image that is probed: Are the silhouettes of the victims of a drone attack in Miranshah, North Waziristan, actually embedded in the pixels of the video image? Is the trace of a Bedouin cemetery readable in the silver grain of a photograph of Palestinian land taken by the Royal Air Force in 1945?

I wish I had been able to include the amateur film footage of the Rodney King case in 1991. During the trial, the prosecutors played the video at normal running speed (in “real time”), whereas the lawyers defending the police showed slow-motion replays. The same images were summoned by the prosecution and defense, brandished each time as irrefutable evidence of contradictory facts!

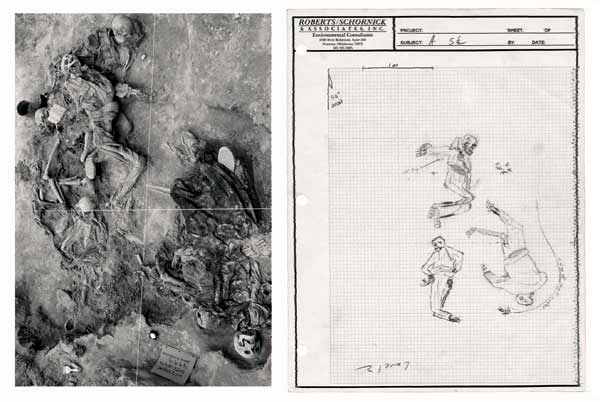

Left: Grave A-South, Koreme, North of Iraq, June 1992. Photo: Susan Meiselas; Right: Drawing with scale and orientation of Grave A-South, Level 2. Drawing by James Briscoe, forensic team archaeologist Grave A-South, Koreme, North of Iraq, June 1992. Photo: Susan Meiselas for Middle East Watch and Physicians for Human Rights mission, May–June 1992. © James Briscoe for Human Rights Watch and Physicians for Human Rights

Aperture: Xavier, as a publisher, why were you drawn to these images and studies?

Xavier Barral: This project interested me immediately because the photographs posed a question about the meaning of images in time and space. To confront the meaning of images is a daily exercise for publishers, yet the cases studies in Images of Conviction cover all spectrums of the image at different times. The same questions come up about the role of the image in constructing our thoughts. Whatever the space that separates us from the subject, the photograph provides distance, correlating elements, from micro to macro, in the case of police images, the X-rays of the Shroud of Turin, aerial photographs, and so on.

Images produced using photographs of Mengele and images of his skull in Richard Helmer’s face/skull superimposition demonstration, Medico-Legal Institute labs, São Paulo, Brazil, June 1985. © Richard Helmer, Courtesy Maja Helmer, 1985

Aperture: Images of Conviction is sober, minimal, fact based, and privileges informative captions and scholarly essays. When you first began working with Diane on the project, how did you intend to translate the idea of the exhibition into the book?

Barral: Often the final edition of the book develops upstream—the book becomes the study of the raw elements of the exhibition. With Diane, we realized very quickly that we had to create a graphic design that would allow the images to be truly legible. Hence the choice of a graphic form that’s factual, that’s as sober as possible. Coline Aguettaz, graphic designer for Éditions Xavier Barral, knew remarkably well how to translate this idea.

The N4005-02 building after destruction, from the archive A Verification of Building–Destruction Resulting from Attacks by the Israeli Occupation, 2009 © Palestinian National Authority Ministry of Public Works and Housing

Aperture: Éditions Xavier Barral has now published a number of books related to archives—This is Mars (2013), L’esprit des hommes de la Terre de Feu (2015)—that bridge the fields of science and art. How do such books fit into your mission as a publisher?

Barral: I have always been interested in new forms of reading and language, and how to find the link between them. The concept of time, and its operations, has always obsessed me—the past and what comes next. When looking at pictures of Mars (in This is Mars), we project ourselves in time. How we look today at the Tierra del Fuego peoples Martin Gusinde photographed in South America in the 1920s (in L’esprit des hommes de la Terre de Feu), how Magellan discovered them in the sixteenth century, how they saw Magellan and Westerners … all these issues there, who saw what and how, through the ages. This prompts a reflection that I’ve fed into the books on time and understanding of forms. One is never able to walk back in time as the photograph invites us to do so. In the book Evolution (2007), the understanding of the vertebrates’ evolution happens through time and demonstrates an evolution of the mind.

“Using a collage pieced together from individual video-frames extracted from the footage we try and locate the building within a satellite image of Miranshah.” Image and caption from the video Decoding Video Testimony, Miranshah, Pakistan, March 30, 2012 © Forensic Architecture in collaboration with SITU Research

Aperture: Many images from the early and mid-twentieth-century studies—Bertillon’s metric crime scenes and the portraits from the archive of Russia’s Federal Security Service—show the faces of victims. You mention the Abu Ghraib photographs in your introduction, but few of the recent case studies from Pakistan and Gaza show faces with the same intimacy or detail. Is it easier to “consume” mug shots, criminal studies, and similar types of forensic portraiture with the distance of time?

Dufour: In the book and the exhibition, each image is inhabited by death. And yet, I think they exude the feeling of being relatively detached from the emotional and the personal dimension of the crimes.

I believe this can be explained through three reasons. First, the exhibition focuses more on image as a means of establishing proof of a crime than the crime itself. Regarding the well-known images of the concentration camps made and shown in 1945 by the U.S., Christian Delage’s film Nuremberg: The Nazis Facing Their Crimes (2007) focuses on the how film directors including John Ford assembled footage of Nazi atrocities. As early as 1942, Roosevelt wanted to gather evidence, “credible facts of the incredible” of the “barbarous acts” committed by the Nazis against civilians in the context of judgment for their crimes. Similarly, when the Nuremberg courtroom was reconfigured for the trials, the screen occupied a central place between the accused and the judge, confirming the dominant position of the images presented in the charge of accusing crimes against humanity.

Christian Delage, Nuremberg: The Nazis Facing their Crimes, 2006 (Still: The courtroom during the screening) © Compagnie des phares et balises

Second, the device of investigation induces a “clinical” visual form, which sets the viewer at a remote distance. Emotional distance is required by jurors to judge the facts in court. The image, as produced or presented by the expert, must be free of any effects. In Bertillon’s images, graduations that line the pictures of the scene deliver mathematical deductions. The book of the destruction of Gaza takes the form of a rigorous inventory, resulting in a “cold” finding of the extent of the destruction (in this case, the destruction or damage of fifteen thousand buildings) following the Israeli attacks of 2009.

Finally, the device dehumanizes both the image and the reality of the crime. Streamlining the extreme visual data of the scene, the image produced by the expert often obscures the personal dimension of the crime, while the image is aimed precisely to identify the victim of violence—and the culprit. For example, in an aerial photograph, it’s impossible to distinguish a man on the ground. Bertillon adopts an overhead perspective, but much closer to the body of the victim, far beyond what can be seen by an investigator: the entire field of the crime scene. The terrifying accumulation of portraits of victims of the Great Purge in the former USSR, between 1937 and 1938, does not focus our attention on the tragedy of every individual, every family, but instead reveals the extent of state collective crime (750,000 people murdered in fifteen months) and dismantles the random and unstoppable mechanism of executions.

The area of al-‘Araqib, image 5033, RAF Palestine Survey series, 5 January 1945 © A British Survey of Palestine, 1947

Aperture: Images of Conviction is a scientific and social document, as well as a beautiful object. Even though the “images of conviction” are not decontextualized, some are nevertheless transformed into highly aesthetic pictures, both in the gallery and in the publication. What are the ethical debates about reproducing these archives today? What would you most like for readers to learn from this project?

Dufour: Neither the exhibition nor the catalogue is voyeuristic. On the contrary, the focus is on the device of investigation and the construction of the evidence by the expert. The exhibition shows that the image is not proof in itself, but instead depends on expert interpretation and mediation to establish the facts.

Barral: These reflections on the image allow us to situate ourselves in relation to actions in the world. Because if something isn’t situated in the world, it disappears. These images are used to define our thinking.

Images of Conviction: The Construction of Visual Evidence is part of the 2015 Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards Shortlist exhibition on view at the Aperture Gallery, New York, through February 8 and Huis Marseille, Amsterdam, through February 14, 2016.