Virginia Hanusik, Raised House in Delacroix, St. Bernard Parish, 2022

In late August 1965, a tropical storm gathered north of Antigua. As it crept toward Florida’s east coast, the storm grew, turned, and moved south through the Bahamas, over the Gulf Stream and into the Gulf of Mexico, before it lashed Louisiana. Hurricane Betsy, as it would be named, killed 75 people, drowned thousands of acres of crops and livestock, flooded an estimated 164,000 homes in New Orleans, and destroyed every building on Grand Isle.

Storms like Betsy, and hurricanes Katrina in 2005 and Ida in 2021, have become central to the stories we tell about the Gulf Coast, stories told in part through photographs, folktales, and news segments. The storms leave more subtle marks: trees molded into strange, curved forms by volatile weather, the patchwork of blue tarps that map the paths of the winds. Evident, too, are signs of human intervention in the landscape. In South Louisiana, engineers shaped the Mississippi River, establishing a series of locks and dams, pump stations, and concrete canyons designed to protect residents from floods. Those structures are just as central to the story of this place as the legacy of those storms.

“Weather and storms are the marking of time,” the photographer Virginia Hanusik told me recently, “before and after.” Hanusik has lived in New Orleans since 2014. Her new book, Into the Quiet and the Light: Water, Life, and Land Loss in South Louisiana (2024), is a record of a decade spent in the region. Photographs appear alongside an anthology of essays and poetry commissioned for the book. For Hanusik, architecture is also a clear sign of time passing; buildings, like hands on the face of a clock, float along a canal one year and disappear the next, while others are raised twenty feet up in the air to escape the coming flood.

Hanusik grew up in the Hudson Valley. Her father was a welder and a sheet metal worker, her mother an electrician. That’s part of the reason Hanusik became interested in the hidden labor that it takes to build a home. She studied architecture at Bard College, eventually enrolling in two photography classes. While she was still a student there, in 2011, she went to Louisiana as part of a volunteer program that began in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, working on outreach for the Broadmoor Improvement Association. After she graduated, while most of her peers signed leases in New York, she returned to New Orleans. She took a job with Propellor, a nonprofit where she focused on coastal restoration and water management. The job took her out of the city, down through the parishes that march south along the Mississippi until it meets the Gulf, often to remote corners of Louisiana. She learned about the places outside the levees, the small communities that lay beyond the federal control structures meant to protect people and property from storm surges and floods. For centuries before there were levees, families made their lives along the river, and despite how precarious it was to live in those areas now, this was still home for those families. Soon, Hanusik found herself driving just for the sake of exploring. And the more that she drove, the deeper her curiosity grew about it all.

“Architecture is endlessly expressive,” Hanusik told me. In the places she visited, “there [are] a lot of funky, interesting ways that people make their own personalities.” Some houses are conventional tongue and groove, raised on marine pilings or cinder blocks, while others, like the Irish Bayou Castle, are eccentric and even strange. Over time, she found that it was this relationship between the people and the landscape that helped her understand “why Louisiana is the way it is now.”

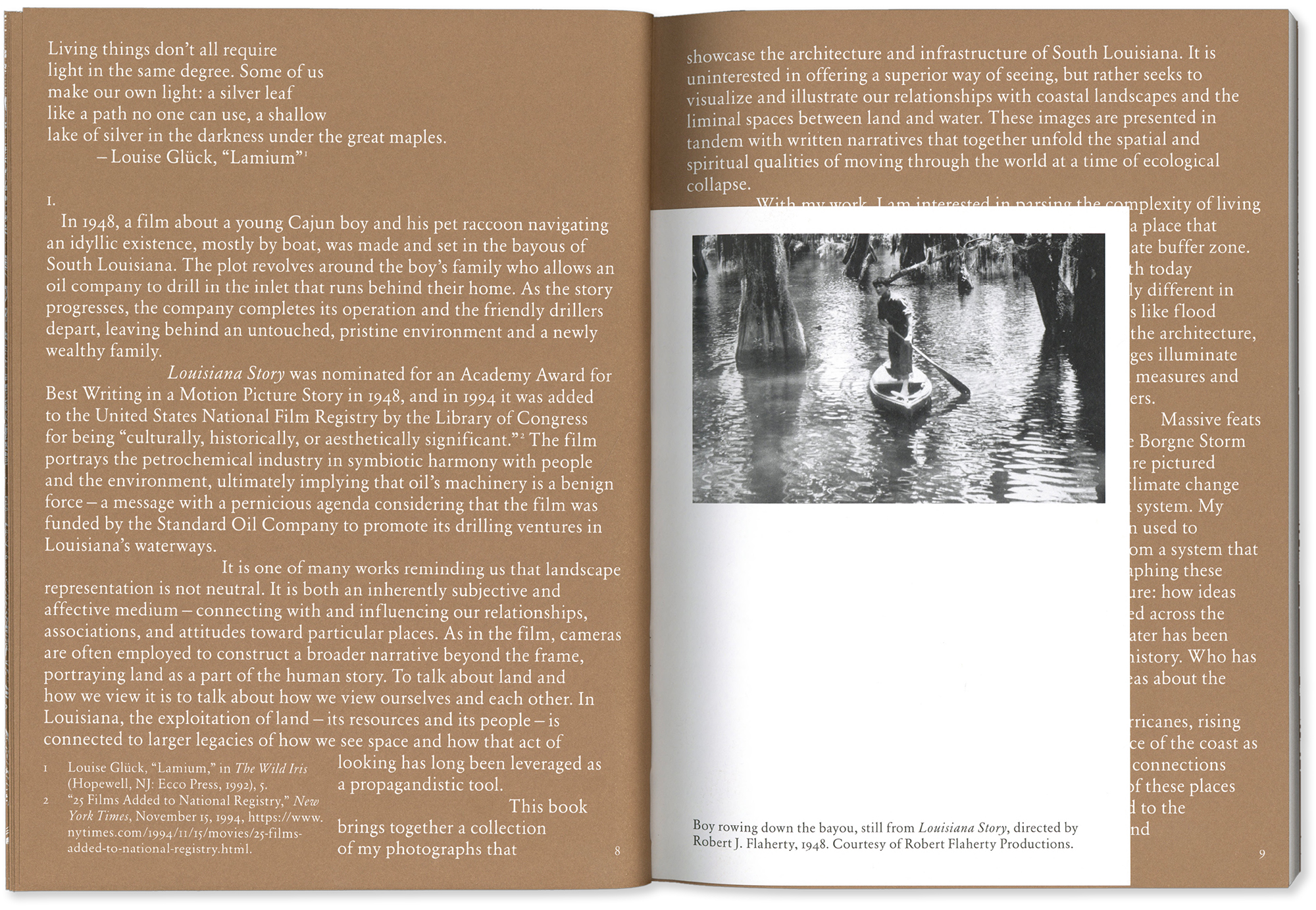

During her drives south through Plaquemines Parish down to Venice or west toward Houma and then down to Port Fourchon, Hanusik started to make photographs, largely of the architecture she encountered: raised homes, vernacular buildings, and the omnipresent traces of engineering projects that attempt to contain the water. Into the Quiet became something much deeper than just a record. It’s a project, she writes in the book, “dedicated to complicating disaster-oriented narratives and the imagery and imaginations that come with them. It is a book about multiple truths existing at once, about looking at the light and the dark and that which meanders between.”

Into the Quiet, published by Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, opens with Harold Fisk’s maps of the oxbows of the Mississippi River, reproduced on the endpapers. After an introduction by Hanusik, her photographs punctuate a collection of essays, reflections, and poems about the region by a diverse group of contributors. The photographs are straightforward and filled with detail, and Hanusik’s own written contributions—among the book’s most compelling aspects—consider landscape painting, connotations of the swamp, and the privileging of certain communities over others in the form of flood mitigation. At times her writing veers toward academic, but it also brilliantly weaves together disparate sources like Louise Glück, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and Robert Adams, from whose 2010 exhibition text for Gone? Colorado in the 1980s she borrowed the book’s title.

Hanusik’s photographs are layered with myriad voices describing their relationship to South Louisiana, revealing how it belongs as much to African culture as it does to European, and speaking clearly to the legacy of chattel slavery and the migration of Southeast Asian immigrants in the wake of the Vietnam War and the Khmer Rouge regime. The photographs are deceptively simple but thoughtful representations of a place shaped by weather and many overlaid strands of culture. “At the core of the project,” she writes, “is an effort to encourage thinking of this region—and coastal communities around the country—as an interconnected system rather than as separate and expendable landscapes.”

All photographs courtesy the artist

I asked Hanusik what it felt like to see Into the Quiet in physical form, to see the end of a decade of work. “There’s some emotional element there that maybe I haven’t been able to fully articulate,” she said. “But it’s a place that I love very much, feel connected to, and I don’t think that will ever go away.” Yet, the cruel irony is that since she first moved to New Orleans, the Louisiana coast has lost around 350 square miles of land. Everyone who loves this part of the country claims some part of that collective grief as an area the size of Manhattan disappears each year. For Hanusik and her collaborators, that grief has often transformed into something else. As she said, “I just have such a deep respect for the ways that Louisianans have lived with water for generations.”

Into the Quiet and the Light: Water, Life, and Land Loss in South Louisiana was published by Columbia Books on Architecture and the City in 2024.