In the Midwest, Alessandra Sanguinetti Blurs Fact with Fiction

The photographer’s latest photobook journeys to Wisconsin, depicting a world of uncanny originality and intrigue.

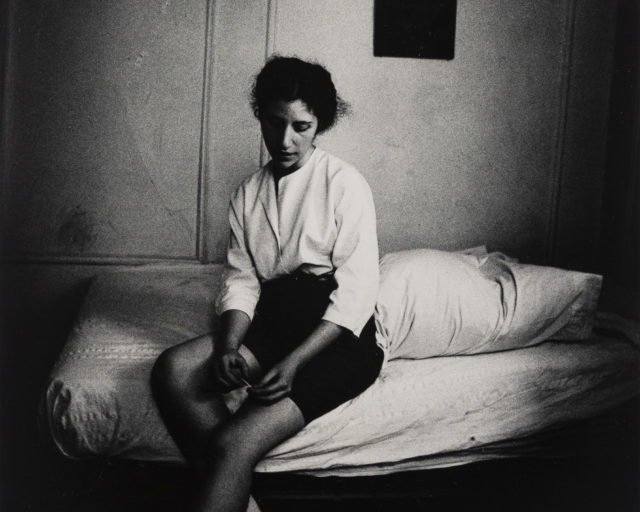

Alessandra Sanguinetti, from Some Say Ice (MACK, 2022)

In the final pages of Alessandra Sanguinetti’s luminous and unnerving new photobook Some Say Ice (MACK, 2022), the artist shares a story of aesthetic awakening from her childhood in Argentina: an unlikely encounter with Wisconsin Death Trip, Michael Lesy’s 1973 work of pseudohistorical, creative nonfiction, spun out of Charles Van Schaick archival photographs bearing witness to a set of grisly events taking place against the backdrop of Black River Falls, Wisconsin, between 1885 and 1900.

Sanguinetti describes the book as inspiring an early connection between photography and death, while obliquely alluding to the grand themes within her earlier work The Adventures of Guille and Belinda and the Enigmatic Meaning of their Dreams (MACK, 2021). Chance operations and the purest inventions of childhood form the wellspring of Guille and Belinda, which follows the entwined lives of two cousins, and where a verdant rural Argentina and its saturated color-wheel wardrobes provide ample drama and insight. It’s a shock, but no surprise, that an artist as attuned to the deeper resonances within childhood play decided, in her most recent work, to play herself in a reverse Wizard of Oz narrative: a Dorothy from Technicolor Oz deposited in an alien black-and-white Wisconsin.

But I’d caution readers against allowing the author’s encounter with Wisconsin Death Trip to serve as an explanation for the mysteries within Some Say Ice, a magisterial fever dream haunted by golden-age Life magazine photographic tropes and related archival déjà vu. As in the best examples of film noir, the progress, as opposed to the plot, unfolds in a series of hairpin turns veering in tone from menace to desire—tantalizing evidence leading to murky but no less compelling dead ends. To conjure a half-dreamt world in which extreme contradictions and behaviors all appear as just another day at the office requires subtle artistry beyond the more familiar, so-called blurring of fact and fiction.

Like Sanguinetti, we’ve seen this town and its local heroes before—many times before. And if you haven’t, perhaps it’s one of those rumored Cold War–era simulated American towns, nestled in the Urals, where whole families of budding Soviet sleeper agents were trained to blend in. It is precisely this swirl of recognitions and doubts that deliver the uncanny originality of both Sanguinetti’s photographs and the unsettled atmosphere of the entire enterprise.

The book’s journey unfolds in a sequence of threadbare rooms, scarred but resilient exteriors, and regular encounters with a cast of animal and human characters, each bringing their granular reality into a dream about a troubled place. Absent of captions or essays, Some Say Ice has the appearance of urgent news from a faded newspaper, possibly published in an alternate universe. A photograph serving as frontispiece displays a target-like TV test pattern, courting allusions to an obsolete TV network’s mix of local tragedy and syndicated entertainment. Closer inspection reveals dates, months and a newborn’s ID card and information more relevant to the workings of a maternity ward. A cropped torso of a long-haired workhorse, recently bathed (or out of the rain?), appears as a remake of a hazy memory, Alfred Stieglitz’s Spiritual America, or an allegory of midwestern plain-dealing, straight from an honest horse’s ass.

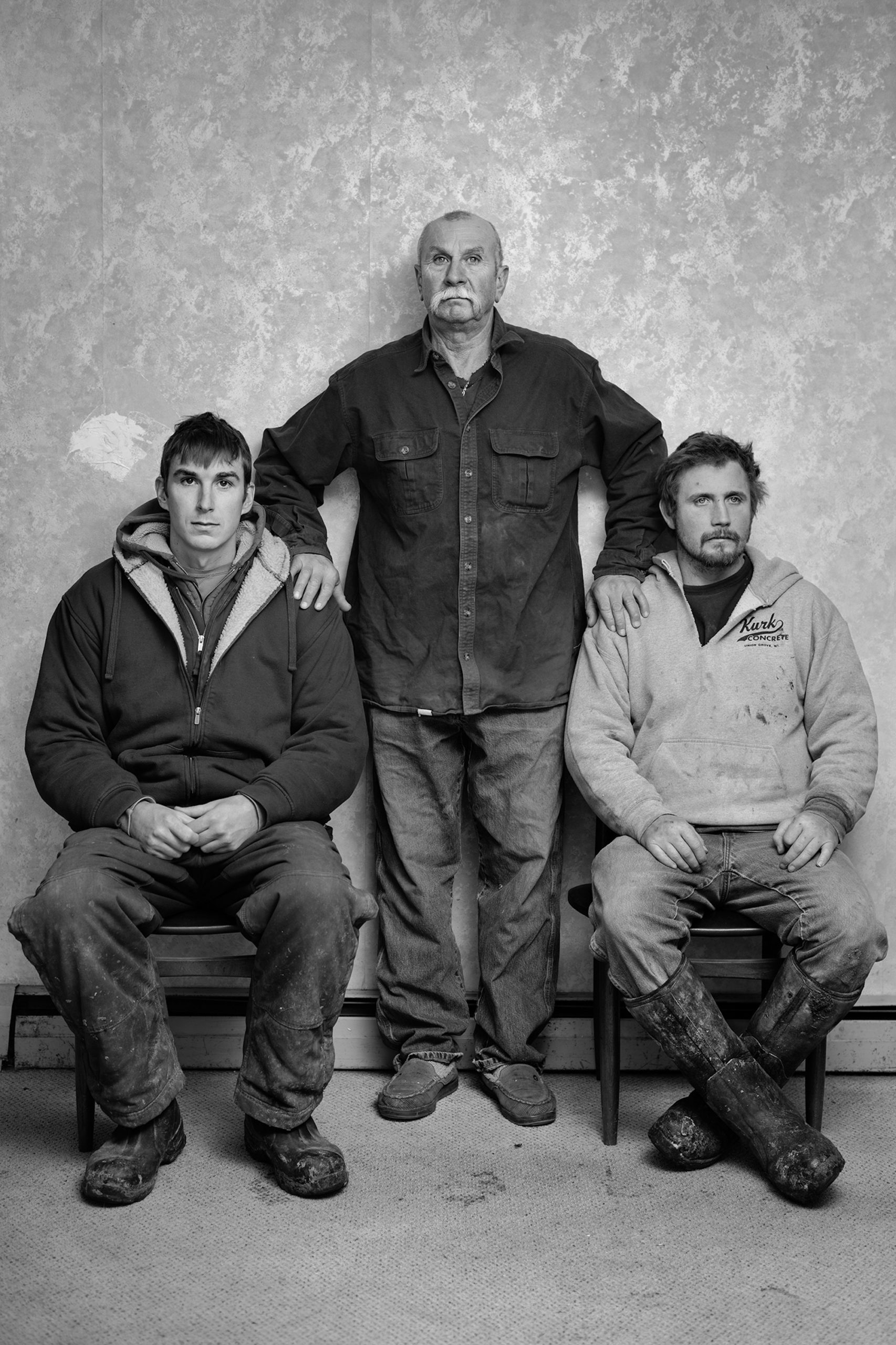

The wild and domesticated, supervised and private, innocent and experienced dance to the beat of agricultural time across and within individual photographs. The formal expectations of a basketball team portrait are derailed by a rogue player’s spontaneous balletics; a fugitive ballerina and her pet parrot; inspired by a rare beam of sunlight against the aluminum siding of a home festooned with a rooftop satellite dish children cast their shadows in a modern shadow-play adaptation of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave.

The world of Some Say Ice is redolent with affinities to cinema, particularly Charles Laughton’s 1955 noir Night of the Hunter, with its ecstatic proto-Lynchian, tangle-of-shadow German Expressionism, and big emotional swings straight out of the Hollywood melodrama playbook. However, where movies must replace doubts with curiosity to achieve the desired suspension of disbelief, Sanguinetti’s imagination is no special effect and her fictions, like her photographs, welcome (and reward) scrutiny because the evidence and the dream are equally compelling and frequently interchangeable.

Courtesy the artist and MACK

While those who wish their library’s poetry section was divided into fiction and nonfiction may be frustrated by unanswered questions about representation and agency within Some Say Ice, ignoring questions of authorship would be to risk missing out on Sanguinetti’s shrewdest trick: her disappearing act. From photograph to photograph, any presumption of an individual photographer with a singular purpose is shredded. Sanguinetti’s necessary invention is the inscrutable entity behind the lens. The questions posed by this unseen photographer-protagonist provide hard-won moments of genuine suspense, with images that thrillingly swerve in motive (and spirit) between wonder, professional kindness, grim knowledge, and an interloper’s instinct to both fit in and get out alive.

Some Say Ice was published by MACK in September 2022.