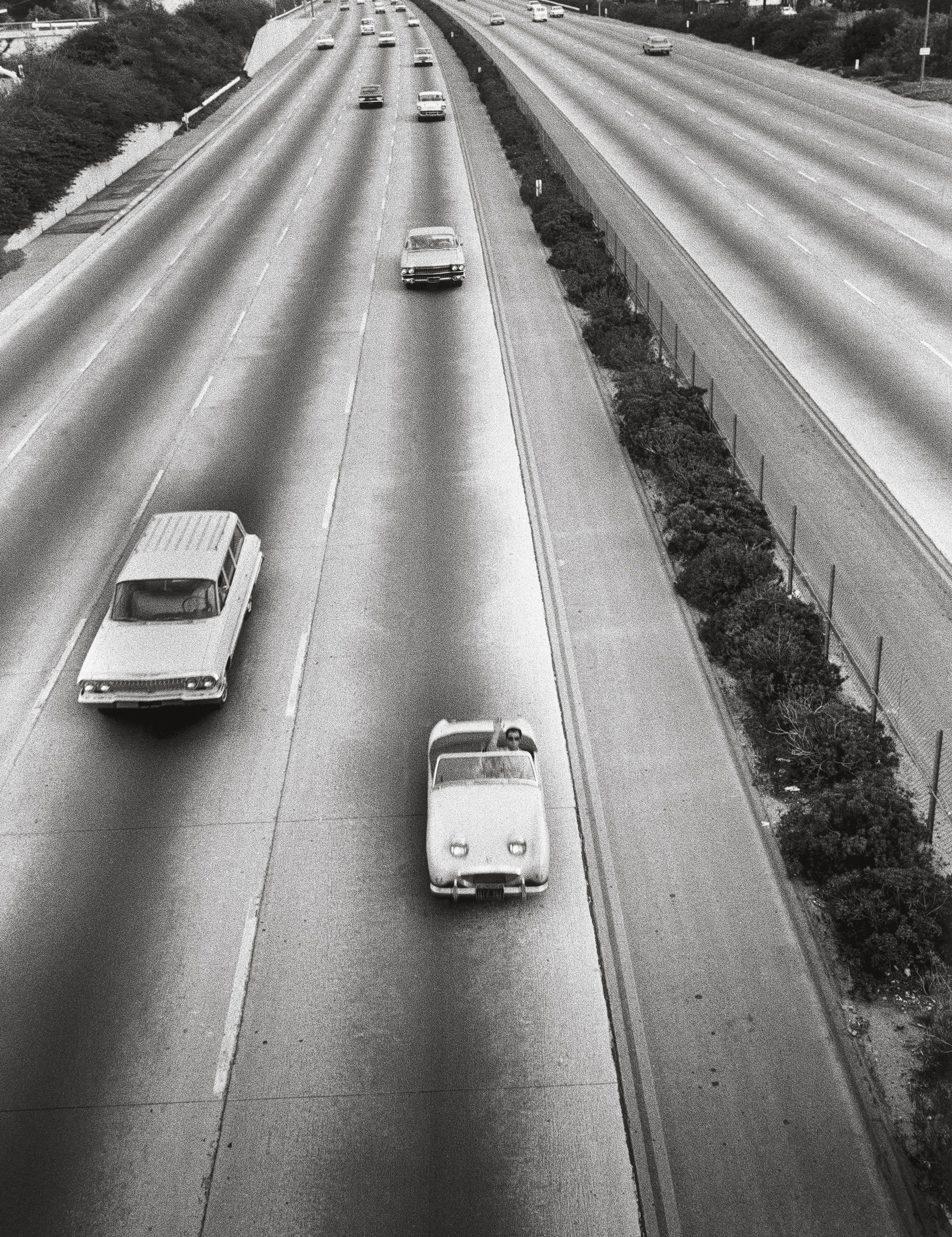

Bruce Davidson, Los Angeles, 1964, from the series Los Angeles 1964

This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 220, “The Interview Issue,” Fall 2015.

“Too much in photography is shoot and leave,” Bruce Davidson says in his conversation with curator Charlotte Cotton. Indeed, Davidson is often intent on looking back—not out of nostalgia for the past but rather to follow the course of his subjects’ lives. This has been the case with those he photographed in a number of his first and most acclaimed series, including Brooklyn Gang (1959); his work documenting the civil rights movement, the 1965 Selma march and the March on Washington two years earlier; and his project East 100th Street (1966–68), on the lives of Harlem residents. Davidson began photographing as a teenager in Illinois, transforming a closet into a darkroom and apprenticing at a local camera shop. While stationed in the military in France in the 1950s, he met Henri Cartier-Bresson, who invited him to join the Magnum agency in 1958. Davidson modestly sums up what defines his ability to connect with his subjects: “It’s about trying to be a human being,” he says.

Now eighty-one, even as he describes ideas for his next photographs, Davidson has been looking back again, this time through his archive, revisiting older bodies of work. Steidl has released a number of new volumes, including Los Angeles 1964 (2015), which may be a revelation for viewers who associate Davidson with New York City, a perennial subject of his. For this interview, Cotton visited Davidson at his home on Manhattan’s Upper West Side last April. There the two spoke about his early infatuation with picture making, about walking the streets of Paris with Cartier-Bresson, and of the constant photographic challenge of getting past the obvious.

Charlotte Cotton: I read recently that in the process of recalling a memory, we literally reposition that memory in a new place in our neural systems, among new experiences—a new context. I find it a really liberating thing to think about, that we are constantly renewing moments from our past. What do you think of that idea?

Bruce Davidson: That means time hasn’t affected the way I see, or what I see, or the joy in seeing. I live with a camera now in exactly the same way I did when I was sixteen. That hasn’t left me—that memory, that boyhood with photography.

Cotton: What were you like at sixteen?

Davidson: Most young boys have a buddy. I had a camera. I was pretty much a loner, and I was doomed to failure because I wasn’t interested in anything other than taking pictures and developing them in my darkroom.

Cotton: When did this start for you?

Davidson: When I was old enough to take the El train into Chicago to take pictures and come home before dark. My mother allowed me to do that. Once she remarried, her husband was a lieutenant commander in the navy and he, like other lieutenant commanders, was given a Kodak camera, which was like a big Leica—it was a range-finder camera. It was quite something. Some of those pictures have survived. The joy of photographing sustains me.

Cotton: Where would you go to photograph when you were a teenager?

Davidson: I would go down to Maxwell Street, which was a flea market. Or Michigan Avenue, the Rookery Building lit up at night. There’s a picture of a woman with a babushka in the flea market from 1950. That meant something to me. Maybe I saw a woman in my family wearing a babushka. But I knew that this person was an immigrant— not homeless, but almost homeless. When I was fifteen and my mother remarried, we moved into a fancy house across from a forest preserve and I would go into the forest to take pictures. I came upon a trailside museum and they had a baby owl sanctuary. And I took a close-up picture. When I was fifteen, I entered the Eastman Kodak high school snapshot contest with that picture, and won first prize in the animal division. Owls live a long time, so recently I called the museum and they said, “Well, if it was forty years ago, we’d say the owl is here, but it’s been over sixty years since you took that photograph and we don’t think that any of our owls are that old.”

Cotton: It sounds like your interest in photography and the change of circumstance for you and your mother coincided.

Davidson: My mother remarried when I was about fifteen and I became interested in photography at ten. I received my first good camera for my bar mitzvah. This was during World War II. I knew it was going to be a good camera. I was so excited about it that I forgot the last four lines of my haftarah and made it up.

I actually started taking and developing photographs when I was ten years old. I was waiting to join a basketball game and a friend called Sammy Nichols said, “Do you want to see developing in my basement?” I said, “What’s developing?” So I went into this Midwestern, dark, dank basement. There was a red light. He flashed a piece of paper and put it in a tray of what looked like water to me, and an image appeared. And that image coming out of nothing excited me to such an extent that I ran home and asked my mother if she would empty my grandmother’s jelly closet— which was small, but big enough for me. And she did. So that was the beginning. I wrote “Bruce’s Photo Shop” in black paint on the door.

Cotton: How did you develop your skills as a photographer when you were young?

Davidson: There was a camera store in town—Austin Camera. They took me on as a stock boy: I dusted the cameras, cleaned the toilets and the floors. And an old country gentleman came in. His name was Al Cox and he had a studio in the town. He told me, “Anytime you want to come by, kid, I’m there.” So I did. He was an incredible craftsman. First of all, he could make dye-transfer prints, so I was exposed to the process. He was a commercial photographer working for the newspaper and I’d go along with him. He would shoot with a Rolleiflex and a flash. Whenever my mother called to find me, I was always with Al Cox. When I was admitted to RIT [Rochester Institute of Technology], Al read somewhere that the first thing I would be doing was pinhole photography, so he made me a pinhole camera with interchangeable pinholes. So he sent me off to college. He could also build strobes and was a ham radio operator. He was a genius old guy—he was an old guy to me.

Cotton: Tell me about the relationship you were forming with cameras and all the material stuff of photography, like chemicals. It’s one thing—which I’m sure we will come back to— to think of photographic capture, of looking and learning about the world through photography. But it sounds like you were also learning through Al Cox about technology and materials of photography and about how to render something, not just capture it.

Davidson: It meant a lot to me. I bought an old 35mm Contax camera when I was at RIT. Walking the streets at Rochester, I found the Lighthouse Mission. It was very atmospheric—a place where these vagrant men would come to get a bologna sandwich and listen to the sermons. I was already exposed to the idea of not a picture but a series.

Cotton: And that would have meant the picture magazines at that time, such as Time?

Davidson: Well, yes. My hero was Gene Smith [W. Eugene Smith]. There were two young women in my class at RIT and one of them had a copy of Henri Cartier-Bresson’s 1952 book The Decisive Moment, and she showed it to me. There was also an inspiring teacher, Ralph Hattersley. He showed us Smith, Cartier-Bresson, Irving Penn, and others. This really sent me in that direction—not imitating, but finding the way I wanted to photograph.

Cotton: What did you feel you were seeing in Cartier-Bresson’s photographs? What resonated with you?

Davidson: The way he saw life. Life was moving; the world was in flux.

Cotton: So did this feel attainable to you—did figures like Smith and Cartier-Bresson seem close

to you?

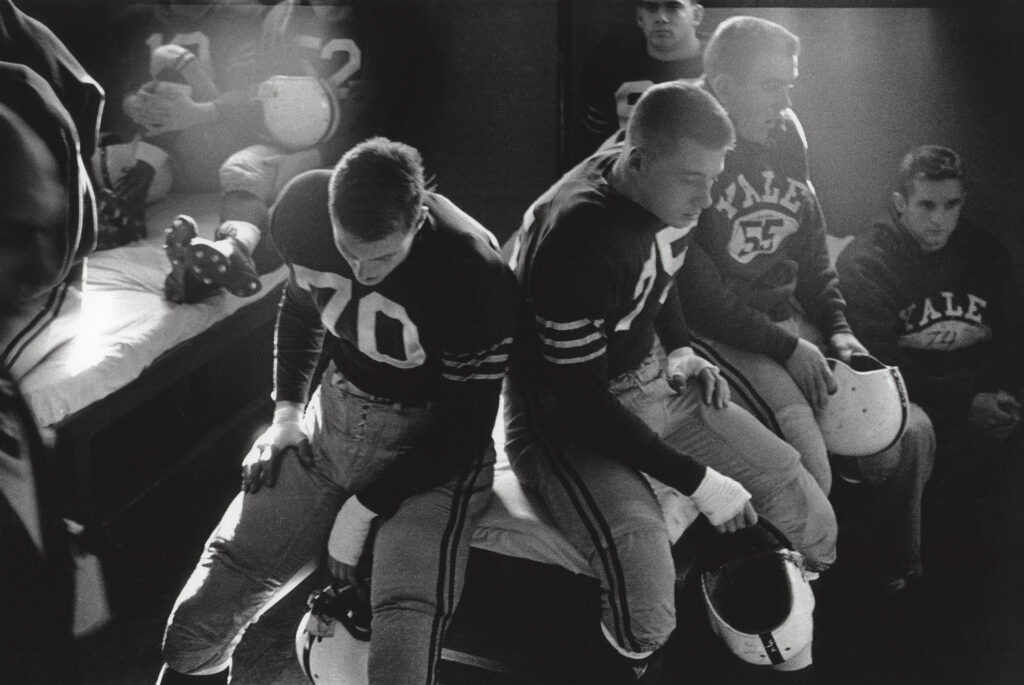

Davidson: Oh yes. There was a gallery in New York called the Witkin Gallery. And Gene Smith used to go there. I used to go up to the gallery and see him and I just couldn’t say anything. He saw that I was doing good work but I couldn’t touch him. Later I really got to know Cartier-Bresson. After college at RIT, I spent some time in the photography department at Yale—I was in the graphic designer Herbert Matter’s class. I was drafted and sent to the Arizona desert, but before I went I photographed the Yale football team, not the game, but the tension and the mood among the players. I submitted the pictures to Life magazine. A year went by, and then they ran them. The captain in charge of the labs had been in the barbershop and had seen my pictures in Life. He burst into the darkroom and said, “Private, did you take these pictures?” I said, “Yes, sir, I did.” And he said, “Take that mop away, you are photographing the general this afternoon.” That was a real decisive moment. Somehow, I got really lucky and I was sent to the photo-labs for the Signal Corps in Paris. I was in the supreme headquarters in Paris and there were French soldiers in this international camp and I took up a friendship with a French soldier who was a painter. He took me home to his mother’s house in Montmartre to have lunch. And that’s when I saw the widow hobbling up the street. “This woman lives above us in a garret,” he told me, “and she knew Toulouse-Lautrec and Gauguin.” I had a motor scooter, so I would go up from the fort to Montmartre to photograph her. That’s when I submitted my work to Cartier-Bresson at the Magnum Paris office. It took a couple of weeks before I got an appointment with him. He was very interested in the contact sheets and the rhythm implicit in shooting. Then I walked outside with him and it was like the street was made up of his pictures. All those moments were there if you could just take a chance.

Cotton: From a young age you seem to have intuitively known how not to take the obvious shot.

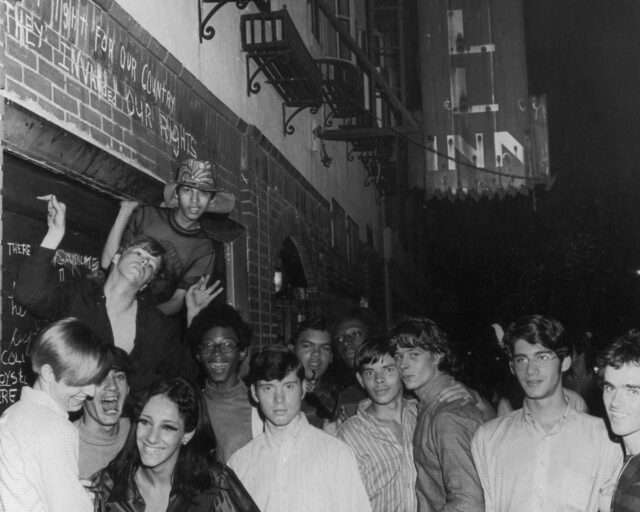

Davidson: I think I’m a less intellectual photographer. I go in and it’s a blank canvas that I have to work with. I start without preconceiving—at least that is true of the work I have made that counts. I have to find my way into a subject—like the Brooklyn teenagers I photographed in 1959 (I published the work as Brooklyn Gang in 1998). It’s a little different for me because I often come back to the scene of the crime. For instance, Emily [Haas Davidson, Davidson’s wife] was interviewing Bobby Powers— the leader of the gang—for over ten years and got to know things that I didn’t. I knew his life was depressed but I didn’t know that they lived in alcoholic poverty, or that his mother had seven children. Emily dug all of this out in her research for Bobby’s Book (2012); her full interviews and my pictures could make another book in their own right, with new information. It was a mood of isolation and the feeling of those kids—although they are now about seventy-five years old, those that are left. About four years ago I was looking at my contact sheets from Brooklyn and there was a picture of a woman smoking and crossing the street with the church in the background. I showed it to Bobby and he said, “That’s my mom.”

Cotton: So you do go back.

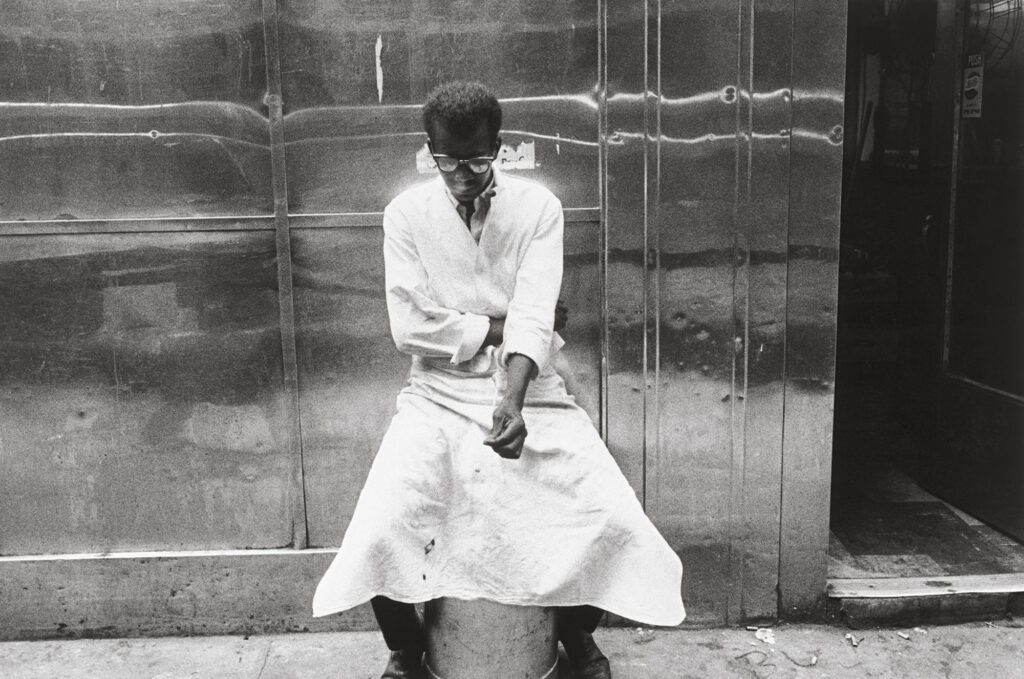

Davidson: Sometimes. It’s a growing realization that maybe a photograph doesn’t end there. In 1965 I photographed the Selma march. I was introduced to a woman named Annie Blackman, and took a picture of her holding her child. She had seven children or so, and Felicia was her youngest. In 2002 I went back on my own to Selma and found many of the people I had previously photographed. I was most pleased to find Mrs. Blackman’s children, many of whom were still living in the same area, and learn how their lives had changed for the better as a result of the civil rights movement. Felicia is now an insurance agent working with local farmers. So that would be one instance of returning to find out where someone ended up. There will be others; I just have to find them. I have a record of them all, and I met everybody. Too much in photography is shoot and leave.

Cotton: Have you been following the conversation about what’s been happening in Baltimore, Ferguson, New York—there’s talk that we are entering a new chapter of the civil rights movement.

Davidson: Oh, yeah. But we’ve heard this story before in Watts [the Watts riots, 1965]. This is about young people, young kids who have nothing in their life except a pent-up violence, because there’s nothing there for them. Jobs, schooling, education, housing—it’s not there for them. Once you crush the atoms, they’re going to explode.

Cotton: How does your approach to social engagement relate to caring about people you’ve photographed?

Davidson: It’s about trying to be a human being.

Cotton: I suppose that’s the permission the camera gives you—to really look at something, to get close to someone and have a connection.

Davidson: It can be a good thing or a disaster. It’s always a challenge to get beyond the obvious.

Cotton: Like the Yale football pictures, you clearly knew what you didn’t want the pictures to be.

Davidson: Well, I had an epiphany. It was my thesis work, and Herbert Matter allowed me to do that as my project. I remember I had an appointment to meet Coach [Jordan] Olivar and he said, “Son, you are much too small for Yale football.” I said, “Well, sir, I really just want to photograph the tension that’s implicit in that kind of combat.” And I never saw the game, because my back was always to the field. I was much more interested in the guys on the bench, or during halftime and seeing all the bandaged players.

I go in and it’s a blank canvas that I have to work with. I start without preconceiving.

Cotton: That’s quite a willful way to take pictures— your criteria are definitely your own. Is that your personality?

Davidson: I think that if you watch a seven-year-old playing—putting together their Lego or superhero toys—I’m not much different. I look at my grandson and think, That’s exactly what I do—I try to put all the parts together. I have fun. It’s just me and reality. Emily and I have been married forty-six years now; she has worked on a lot of projects. When we were first married, I was ending my project on East 100th Street.

So I decided to take Emily to a circus in Ireland—Duffy’s Circus—on our honeymoon. We’re going to a place where it rains every day? With circus people? But it worked out well [laughs]. I wanted to take a picture by climbing up to the top of the tent to look down at the trapeze artist. And Emily was below holding a strobe light, but she had the strobe facing the wrong way. So I wrote on a little piece of paper, “Move light left,” and I dropped it down and she thought it was something from heaven, that she must get it. She turned it over, looked up, and said, “Okay, okay.” It reminded me of La Strada [film by Federico Fellini, 1954]; she was my Gelsomina.

Cotton: You’ve given me a good sense of the beginnings of projects, as not being preconceived, and that you are really open to what is in front of you. I’d like to know more about completing projects. When and how do you know that they are finished?

Davidson: When you can’t do it anymore. You have to be careful not to do something that will stop it in the middle. Like any relationship, you can lose the passion that’s provided you with the excitement to photograph. And there’s the challenge of continuing to find something when that excitement isn’t there anymore. I don’t have the time now to wait as much, so I have to give up. In gaining something you may lose something.

Cotton: And I guess it is also a question of sustaining the motivation to work with a subject. I mean, when I come away from seeing you, I always feel that we talk about human beings, fairness, seeing things—a very personal version of the political. Some of your projects are outwardly political, and they clearly express a view about the world.

Davidson: Everything is political. If you burp—it’s political. The difference between myself and my daughter Anna is that she is a farmer, and she’s married to a farmer, so farmers see her as a farmer, not a photographer. So they are very comfortable with her taking photographs. I didn’t have to be black or Puerto Rican to take photographs on East 100th Street, I just had to stay there long enough for people to understand what I was about. And I still, to some extent, have a relationship with those people.

Cotton: Are you expecting us to read that into your work—not, as you say, that you speak from the position of an activist exactly, but that you believe people should see and acknowledge what you are seeing?

Davidson: That’s what my Los Angeles photographs of the foothills (2008–13) are all about. It’s beautiful, set against the city grid. I was thinking today that it’s not going to be my most known work, but you have to give me credit for going from the East to the West Coast. I enjoy nature, and getting out there. And even if these photographs don’t end up hanging in museums, they are about me and about being really free. I stayed at an apartment hotel in Santa Monica. I bought a dark cloth and turned the closet into a darkroom.

Cotton: You have a history of closet darkrooms!

Davidson: It’s an old 1940s hotel with a kidney-shaped swimming pool, and with huge closets. That became my darkroom for loading film. So my assistant would pick me up at 9 AM—

Cotton: Well, I remember that you were often getting up to photograph much earlier than that—I was really struck by how hard you work. I was quite exhausted by your schedule from a distance!

Davidson: It is hard. Because it’s about light and finding a place to photograph with a few shots. At the end of the day, I’m exhausted; I get some food and go back, and I’m famished. I have to eat and then I fall asleep, then I get up at 2 AM, wash my hands, load the film into my camera … so that cycle is really healthy for me [laughs]. I can’t manufacture an idea. There has to be something—a tension. I’m thinking of photographing different parts of New York City, to find things. It will be in color—it has to be simple, and during the day, because we will be walking around. Like, on the corner here, there is an Egyptian father and two sons with a coffee van. They make the best coffee around. It’s a dollar a shot—we get three dollars’ worth every morning. I like to know where they came from; I like the way that they almost dance as they work. But I haven’t taken the photographs. Yet.

Cotton: Your Los Angeles 1964 project is about to be released.

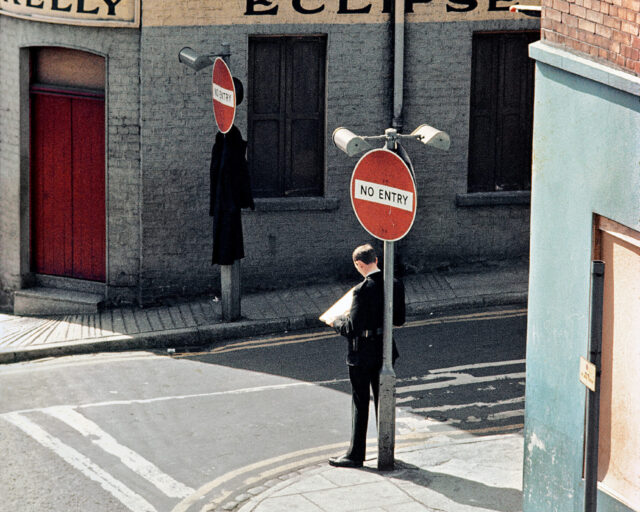

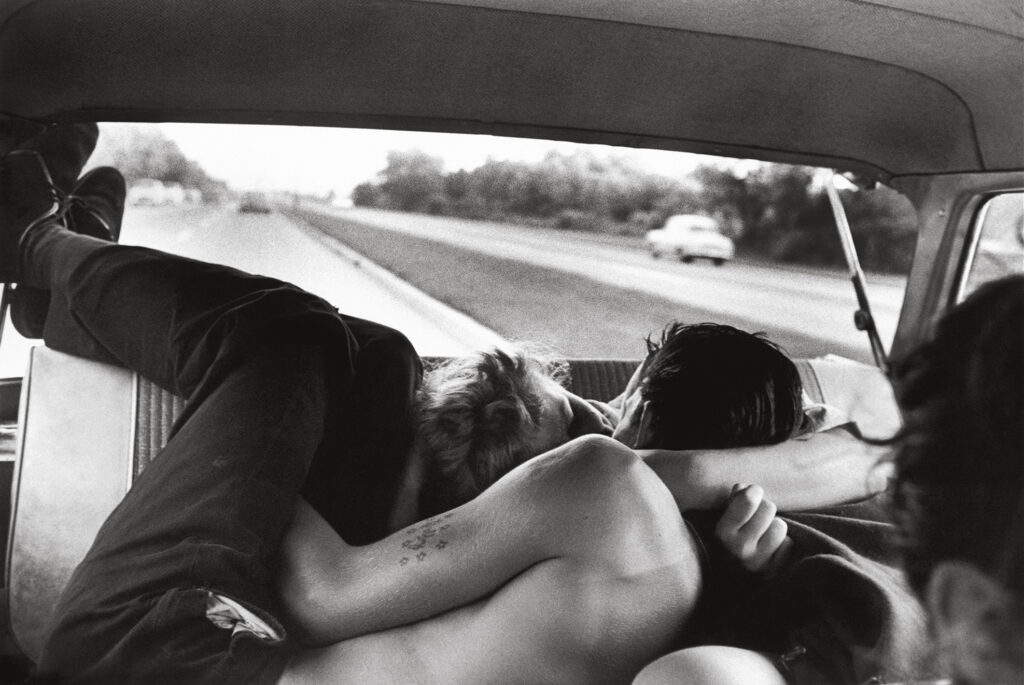

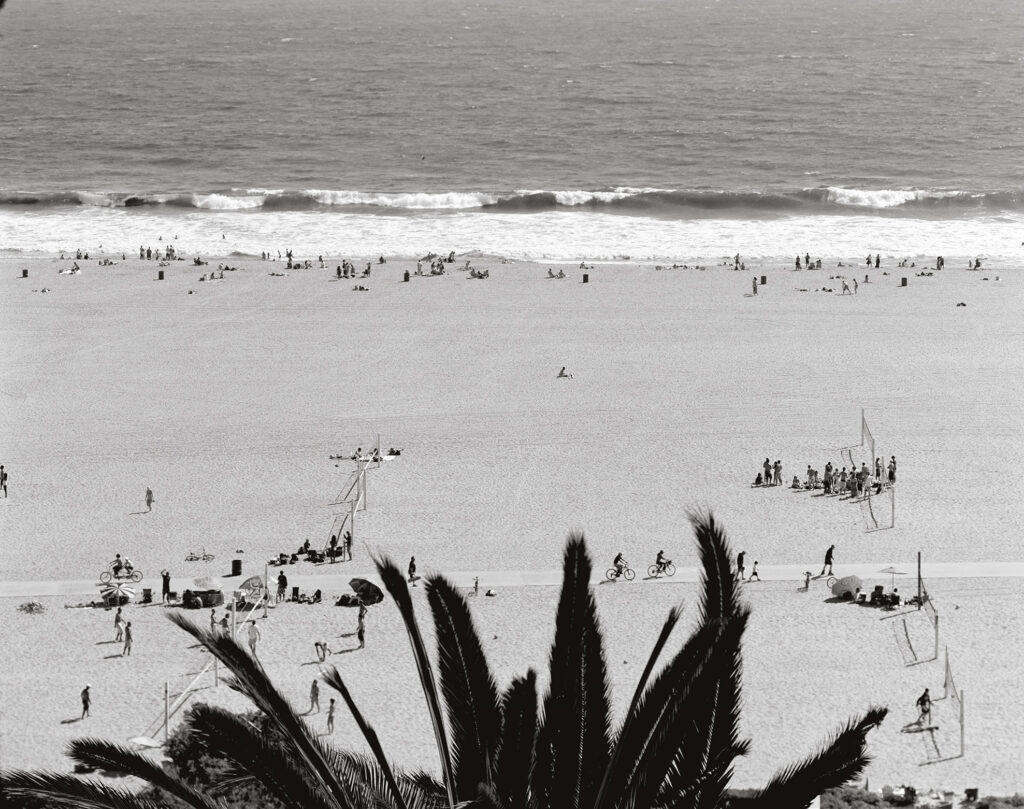

Davidson: When Esquire asked me to go photograph LA [in 1964], I didn’t know anything about LA. I get there, and you need a car, and it’s smoky; your eyes tear, the pollution, and people are sort of catatonic, in a way. So I photographed that. I handed them in to Esquire, and they didn’t know what they were about. It wasn’t the LA they were looking for. So they returned all the pictures to me, and they sat in my drawers for years. They evolved, once we understood the hostility in that city at that time.

When I came back to LA, twenty or thirty years later, it was different. I saw it in terms of a landscape. Take the Hollywood sign, for example. Everyone looks at it and takes a picture of it. I managed to find someone who could place me behind it. So I was photographing what it sees, and what it sees is a scrub desert. I explored the hills in relationship to the highways—the highway grid. I began to see the grid in terms of the nature that surrounded it, and the beach, but the beach allowed parking on the dunes, on the sand. In LA the beach is a parking spot. Anyway, later I explored those things. The rich vegetation, the desert, the foothills, and the beauty of the palm trees. I thought the palm trees were a poem.

All photographs © Bruce Davidson/ Magnum Photos

Cotton: You’re originally from the Midwest, but I think of you as a true New Yorker, and New York has been a perennial focus in your work, including Brooklyn gangs, and the subway, and Central Park. Could you comment a little bit, just in contrast to LA, for example, about New York as a subject?

Davidson: I always start with a blank canvas. Every body of work comes out of a different state of mind, and I really have to be in a state of mind to be drawn into this black hole of reality.

Cotton: How would you describe that state of mind?

Davidson: You have to feel some pressure, something that you need to find, something that’s calling you. In the subway, it was the movement and the color of movement. The subway became a studio for me. It was a place where I’d go every day just to discover whatever it is that I’m allowed to see.

Cotton: Do you still ride the subway in New York?

Davidson: Oh, yeah. And I still get lost.

Cotton: I’m also thinking about all of the disciplined work you have been doing over the past few years going through your archive, selecting and printing, and, of course, publishing with Steidl. What do you think you have learned in the process of looking at your archive?

Davidson: There are surprises. Sometimes I come across a pile of pictures that I have overlooked. Now, we are discovering pictures of myself [laughs]. It’s very before and after. But there are an awful lot of pictures to be made, and as long as I can physically do it, it’s great. It was only when I turned eighty that I said, “My god, I have turned a corner in my life … eighty is almost ninety. Maybe I should get a digital camera, and I’ll just go places, and no one will see these pictures.”

This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 220, “The Interview Issue.”