The Photographer Whose Mother Built Trump Tower

In 1978, when Donald Trump met Barbara Res, he called her a “killer.” Barbara was then one of the few women working as a construction engineer in New York, but after Trump witnessed her berating male workers renovating the Grand Hyatt on 42nd Street (Trump’s first major Manhattan real estate project), he snapped her up. “He said men are better than women, but a good woman is better than ten men,” Barbara recalled in 2016. She would go on to manage the construction of Trump Tower, and pictures of her at the Fifth Avenue construction site in 1980—with her hard hat and wraparound sweater, standing as if on a dais amid scaffolding far above a foundation pit—evince her formidable self-possession. “I was that woman,” Barbara said. She was thirty-one years old.

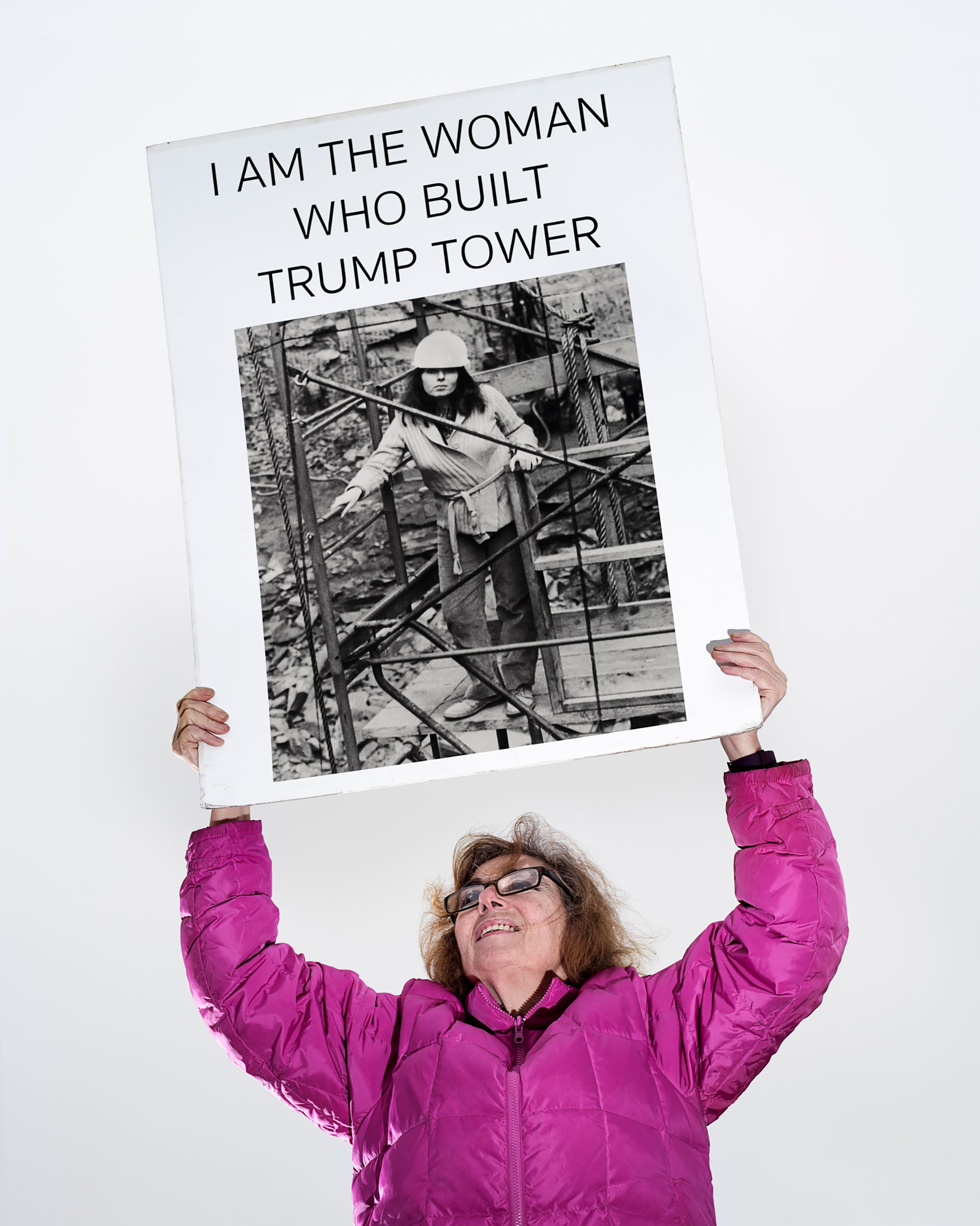

The photographer Res turned thirty-one on November 8, 2016, the day Trump was elected president. Res was at the Yale School of Art at the time. “The sculpture department threw a party for me and it was the worst party you could imagine,” Res said recently over Zoom from Sweden, where they are currently living. The day after Trump’s inauguration in January 2017, Res and their mother, Barbara Res, joined the Women’s March in Washington, DC. Trump Tower was part of Res’s mythology as a child: Res had pored over profiles of their mother in the magazine Savvy Woman; the mauve Trump Tower marble was as familiar as a household rug. But Barbara had long since left the Trump Organization, and in 2016, she began to speak out against her old boss. Her media appearances provoked a typically offensive tweet from @realDonaldTrump: “I gave a woman named Barbara Res a top N.Y. construction job, when that was unheard of, and now she is nasty. So much for a nice thank you!” For some women, “nasty” is a badge of honor; at the Women’s March, Barbara held aloft a sign that read, “I AM THE WOMAN WHO BUILT TRUMP TOWER.”

Res, Spread from Towers of Thanks (Loose Joints, 2017)

Res grew up in New Jersey and studied photography at Smith College. They started out experimenting with self-portraiture, but “the faculty were just so tired of ‘women’ constantly using themselves as subjects,” Res said. “We were kind of asked not to do self-portraiture.” Later, in 2015, Res—a self-described “jock” who once trained as an amateur boxer—began a project about their father, who had recently lost his job and was spending all his time at home. Res was at Yale, and they would return to New Jersey on weekends, collaborating with their father on what would become the series Thicker Than Water (2015), a speculative family portrait tinged with dramatic shadows and neonoir flair. Res and their father had drifted apart, but the project became a way to relate and mediate feelings about queerness, masculinity, unemployment, and family expectations. Res was motivated to “witness him,” they noted in an interview for MATTE magazine in 2016. “He spends so much time alone and unseen, so it felt special to me that I could put my eyes on him, that I could value him in that way.”

One of the most striking photographs in Thicker Than Water is a self-portrait of Res dressed as Barbara. Res wears Barbara’s wig and an ill-fitting red bra. Barbara did Res’s makeup, pouty lipstick and overapplied rouge. Surrounded by heavy liner, Res’s glowing eyes look searchingly into some faraway distance. As Barbara, Res appears neither behind a mask nor fully embodied; like a Cindy Sherman Hollywood/Hamptons self-portrait or a Duane Hanson sculpture, the uncanny tension between life, image, and pose is unsettling. Res tattooed “Butch” on their chest for the image, which they describe as “one hundred percent” drag: “Drag as my mother. Drag as a woman.” “It is a funny picture,” Corrine Fitzpatrick notes in MATTE, “awkwardly performed and thoughtfully, committedly, composed.”

Elsewhere in Res’s practice, the body and the figure take on similarly sculptural forms. In one image from the series Read You (2013–15), Res captures a subject in a black bra who, as she pulls off a mustard-yellow sweater, obscures her face like a lone René Magritte lover. “I was trying to think about how to describe intimacy outside of the reveal,” Res said. “Sometimes what we don’t show, or what we don’t display, is just as much of a reveal.” Just at the moment when the subject in Stevie (2014) may become known to us by her face, all we can see is outline, as well as a doubling in the form of a shadow on the wall—a totem, a smoky silhouette. The drop of sweat from Stevie’s armpit is the punctum. “And that being kind of what’s out of control,” Res said. “This beautiful gesture of it dripping.”

But sweat, for all of its associations with physical lust, becomes a tragic substance in Res’s series Pulse (2016), made in the aftermath of the mass shooting in 2016 at the eponymous gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida. Res was driving to Florida for a residency when alerts began to arrive about the massacre. They began to visit the makeshift memorial that had materialized in Pulse’s parking lot but decided against making portraits of survivors or witnesses. Instead, Res was moved by the temporary walls erected of chain link and shrouded in black cloth, into which visitors stuck flowers, signs, and rainbow flags. They were “poetic articulations of public mourning,” Res said, noting that the sweat and the humidity in the parking lot was like the enclosed space of a nightclub. “You think about being in a club, the last breath of these flowers. You’re seeing them die.” Separating life and death, the memorial fences seemed to contain a form of evanescent queer memory: fierce, colorful, and operatic.

In all of their work, Res searches for bonds between people, from the nuclear family in the household to the contingent family of a protest. Res’s self-portrait as Barbara makes a cameo in Towers of Thanks, Res’s 2017 photobook about their mother. Doing overtime as a specific impression and a seemingly universal gesture to the performance of femininity and motherhood, the image fits alongside pages of Res’s photography and collaged vintage images of Trump Tower, news clippings from Barbara’s heyday. At thirty-one, Barbara was atop Trump Tower, a powerful woman working to realize a man’s dreams. At thirty-one, Res was down on the street with Barbara, both their voices shouting together with thousands of others. But history has a way of haunting the present. After the completion of Trump Tower, Barbara was given a Cartier bracelet engraved with the words “Towers of Thanks.” When you turn the bracelet in your hand, another line appears in elegant cursive: “Love, Donald.”

All photographs courtesy the artist.

Read more from our series “Introducing,” which highlights exciting new voices in photography.