Italy’s First Photobook Festival

Marina Arienzale and Matteo Cesari, Self-organized afternoon dance with live music and snacks, Quinto Alto, Florence, 2015–17

Courtesy the artists

Once a year, in September, a photobook festival vivifies the quiet town of Punta Secca, a tiny fishing village in the southern region of Sicily. Photobook lovers flock here to discuss, brainstorm, teach, and learn about photobooks. Gazebook celebrated its third edition this year under the direction of photographer Lina Pallotta, and highlighted projects that are socially and politically engaged, especially with partners and artists in the Mediterranean. Here, Pallotta speaks about the latest edition of this burgeoning festival, where people bring their own chairs and sip lemonade under the trees.

Giada De Agostinis: The festival includes an open call for slideshows called Slideluck, organized by Mariateresa Salvati. Could you tell us more about this endeavor?

Lina Pallotta: The open call is a way to give visibility to new talents and projects. We want to empower multimedia, and not merely using one image after another with background music. As magazines now feature more multimedia stories, we feel the urgency of challenging photographers to explore how to use multimedia.

Marina Arienzale and Matteo Cesari, Card game, Sesto Fiorentino, Florence, 2015–17

Courtesy the artists

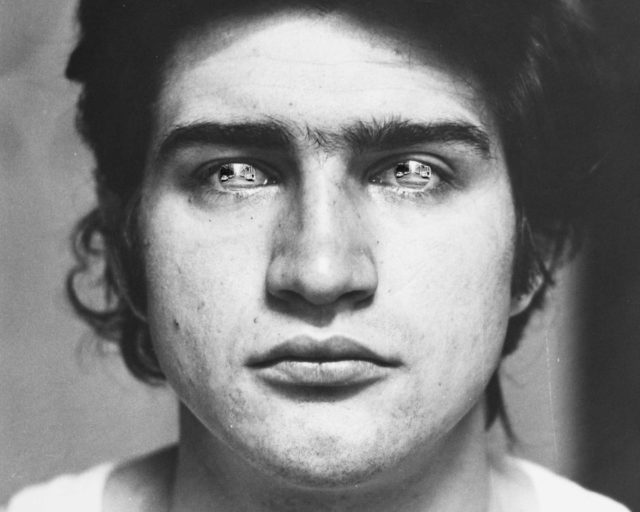

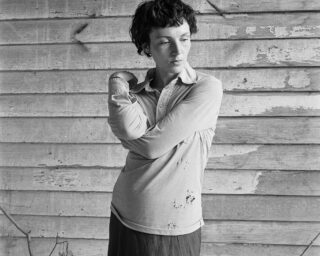

De Agostinis: One slideshow is Marina Arenziale and Matteo Cesari’s Casa del Pop. What is their project about?

Casa del Pop documents Tuscany’s community centers, originally linked to the Communist party, which became recreational centers within the cities. These photographs show a peculiar aspect of Italian culture and political history. I think it’s an important visual record of our country. The work is focused on Tuscany, where there is a widespread presence of these Casa del Popolo—meeting points where working-class people used to participate in social, cultural, and political activities. In some cases, especially in small towns, they were the places where people congregated, as opposed to the churches. Now, these recreational centers seem to have lost their original identity.

De Agostinis: Lina, I know you’re a photographer, an educator, and a curator, and that you divide your time between Rome and New York. How do you navigate your roles on two different continents?

Pallotta: I used to be a full-time photographer. I was working in editorial photography in Italy and doing freelance work in New York. Back then, if you didn’t photograph, you didn’t make money. Now, things have changed. Even if you photograph, you don’t make money! Teaching was the best way to convey my ideas about photography, of spreading my vision about images. I curate exhibitions in Italy so I can show projects that otherwise would not be seen here. The dialogue around photography in Italy is still narrow and concentrated on photojournalism and reportage, while the current exploration abroad opens the medium up to endless possibilities. In some ways, living between the U.S. and Italy has allowed me to travel through time.

Marina Arienzale and Matteo Cesari, Senegalese worker, Santa Croce, Pisa, 2015–17

Courtesy the artists

De Agostinis: You curated the third edition of Gazebook this year. It’s a challenge to start a photobook festival in Italy, and even more so in Sicily. Do you feel the village inhabitants are engaging with the festival?

Pallotta: Yes, this year the population of Punta Secca really welcomed us for the first time. They actively participated in the talks, and even brought their own chairs to be sure they would have a seat! The situation in Sicily, and elsewhere in Italy, is depressing as funding for art and cultural projects is lacking. Nevertheless, the festival has grown in these three years. Although institutions don’t help, we see local people supporting us. In a way, it’s easier to find our own crowd there, rather than in big cities, where there is more competition.

De Agostinis: Gazebook is probably the first festival in Italy that has a focus on photobooks. How did you come up with this idea?

Pallotta: Books are extremely important in the contemporary photography landscape. Collaborating with different partners—designers, editors, publishers, et cetera—has become essential to photographers. Twenty years ago, print magazines had higher circulation, so there were many more photo stories being published. As magazine circulation has declined, self-publishing and photobooks have flourished.

Marina Arienzale and Matteo Cesari, Theatre of the House of the People, one of the largest theatres in the area, Grassina, Florence, 2015–17

Courtesy the artists

De Agostinis: The topic of this year’s festival was “Visual communication in uncertainty and chaos.” There was a wide representation of Muslim artists from around the world, and projects about Islamic countries, which resonates with Sicilian history, where the Arab influence was monumental a millennium ago. There’s also a proximity to those waters where migrants arrive each day. For example, photographer Karim El Maktafi’s Hayati (2015–17) considers his double identity being Italian and Moroccan.

Pallotta: Yes, Karim El Maktafi was born in Italy from Moroccan parents. Through his work he tries to find a balance between those two cultures. Or, in her series Clothbound (2014), Leila Fatemi uses diptychs to show how she wants to direct the conversation about Muslim women. Fatemi is a Toronto-based photographer of Iranian, German, and Indian descent. On the left of each diptych, the pattern of a woman’s veil merges into the background, obscuring her figure; on the right, her face is revealed and her power asserted through her gaze.

Amak Mahmoodian’s book, Shenasnameh (2016), investigates Iranian women’s individuality through a collection of Iranian birth certificates, which are also used to record marriage, divorce, and include fingerprints. In their official photographs, women must wear a veil and no makeup. Mahmoodian turns homogenization into a tool for asserting these women’s different stories. In Italy, the perception of the Islamic culture is a contested topic, and we are constantly debating about immigration. People do not dare to call themselves racist, but, once people with different skin colors and religions started flocking to our country, their attitudes became controversial.

De Agostinis: You also included a selection of book dummies from Istanbul Photobook Festival.

Pallotta: Yes, this is one of the partnerships we’ve launched this year, together with other initiatives from the Mediterranean. For example, we hosted a talk by Issa Touma, a Syrian photographer and filmmaker who created the first gallery dedicated to photography in the Middle East, in Aleppo, Syria. Issa presented his new movie, Greetings from Aleppo (2017), which opened at the International Film Festival Rotterdam.

Marina Arienzale and Matteo Cesari, Billiard room, Rifredi, Florence, 2015–17

Courtesy the artists

De Agostinis: During the festival you hosted a talk with Jason Fulford, who presented his project Fake Newsroom (2017), a project inspired by Newsroom (1983), created by Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel, where artists were using images from a news wire photo service and re-contextualizing them in a gallery. How do you think this project relates to our current political climate?

Pallotta: Back in the ’80s, the Newsroom project was conceived to let us question what we see in the media. Magazines dominated reportage and social issues, and the project showed us that nothing is objective. So, it was about opening up this monolithic culture of photojournalism. The current project has a narrower dimension, focusing on one binary: true or false.