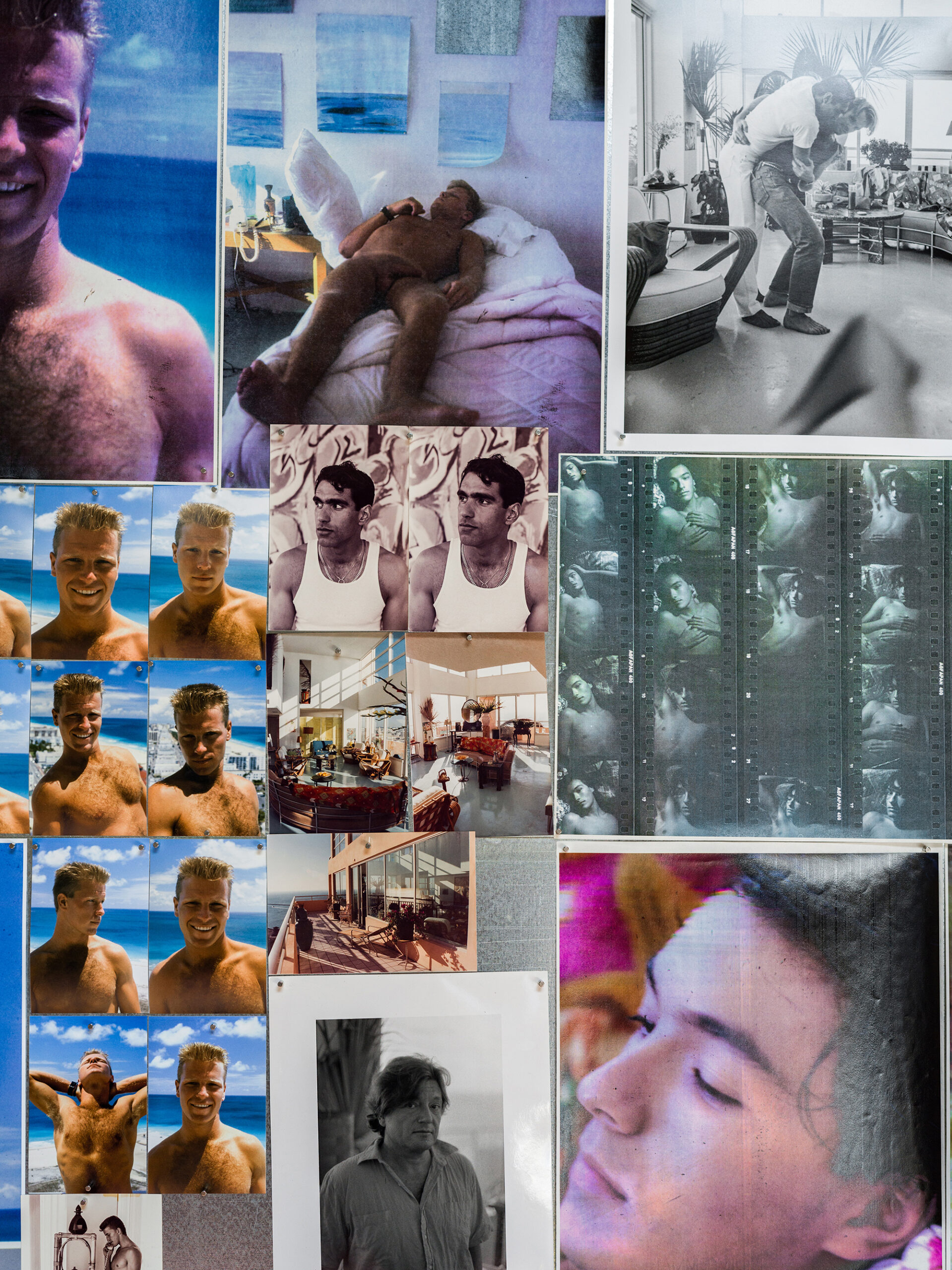

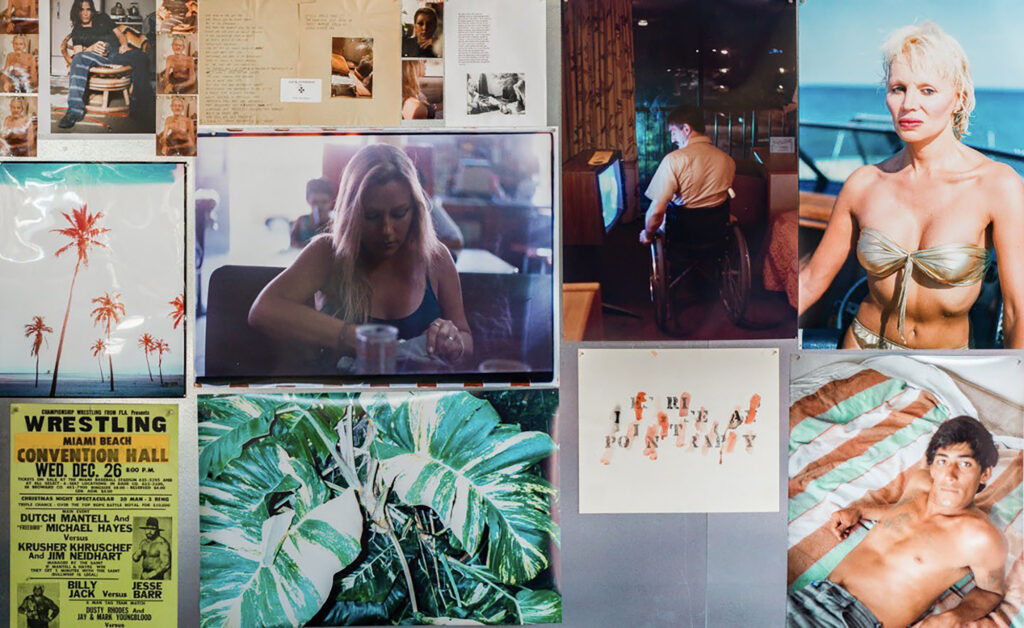

Jack Pierson, ARRAY (MIAMI), 2025

In 1984, Jack Pierson drove to Miami from New York, intending only a brief vacation. He ran out of money, found work bussing tables in South Beach, and stayed for six months—an interval he would later describe as among the happiest of his life. By the early 1990s, Pierson had already mythologized this period, transforming it into the subject of his first New York gallery exhibition, which paired snapshots of Miami friends and neighbors with installations recreating domestic scenes from his apartment there. The Miami Years, organized by the Bass Museum and currently on view through August, revisits this formative chapter by bringing together photographs and paintings made in the mid-1980s and later works that return to the imagery and cultural typecasting Pierson first developed during this era. Installed within the Bass’s coral-rock Art Deco building, just blocks from where Pierson once lived, the exhibition gains added resonance from its surroundings in a district that was once a center of gay life that has since been largely gentrified out of existence. The following conversation took place inside the exhibition and reflects on Miami as both a lived experience and enduring imaginative site within Pierson’s work.

Courtesy The Bass

Matthew Leifheit: Here we are in your show. How did this come to be?

Jack Pierson: They approached me like a year and a half ago, told me about the series that they were doing called The Miami Years, and knew that I had spent some time here in the ’80s.

Leifheit: Oh, it’s a series of exhibitions called The Miami Years?

Pierson: Yes. Because the last one was Rachel Feinstein who grew up here. And then Nam June Paik spent time here, which I didn’t know. The last ten or twenty years of his life, he kept a studio here. I had no idea. And so this is the last of the series.

Leifheit: You started coming down here in what year?

Pierson: I came down Christmas ’84 and wound up kind of being stranded until June of ’85. Came down for Christmas vacation, had no intention of winding up here, but I ran out of money and started to really enjoy it. So we took jobs.

Courtesy the artist, Lisson Gallery, and Regen Projects

Leifheit: Who did you come down with?

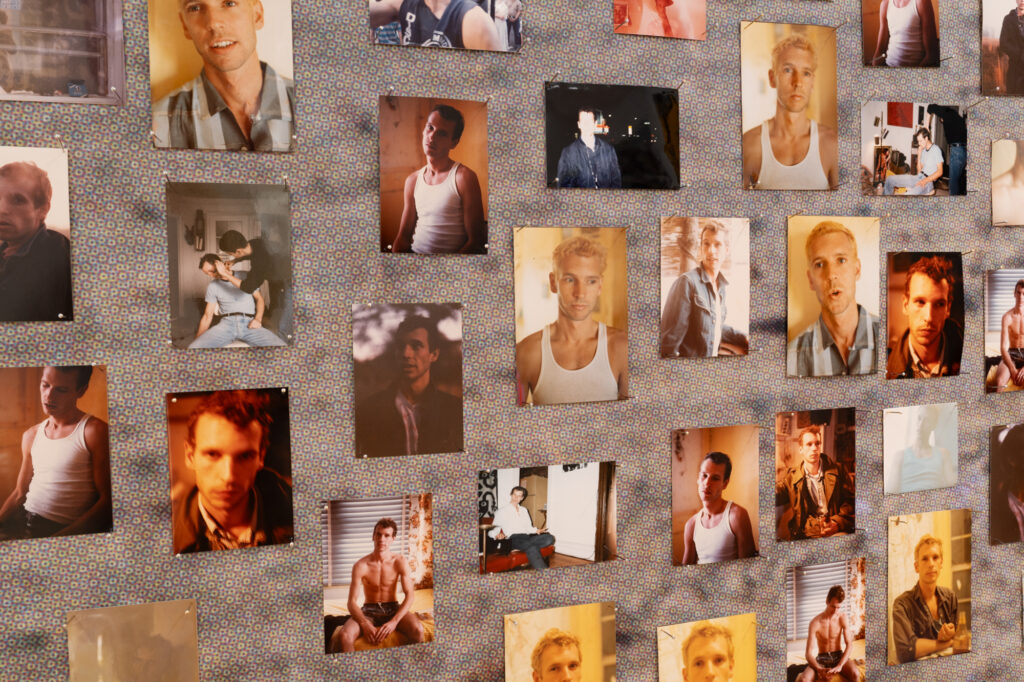

Pierson: I came down with Andre, who’s the subject of this cloud of snapshots.

Leifheit: And Andre was like a boyfriend?

Pierson: I was trying to force him to be my boyfriend. And ultimately, I had some success, but it took a long time.

Leifheit: What was the resistance?

Pierson: He just wasn’t as into me as I was into him, but I finally wore him down.

Leifheit: Where were you staying at first?

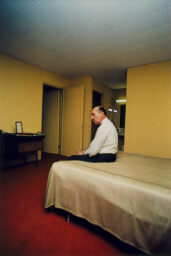

Pierson: That’s the first room we landed in—a hotel room on Ocean Drive, way down near Third Street across from the park. We had driven straight through and just crashed for two days. When we woke up, I took that picture of him.

Courtesy The Bass

Leifheit: And the rest of these photographs?

Pierson: The rest of these are from that time between Christmas and June. Or New York—some are from New York before we left. This is his first day. I got a job at Wolfie’s, which was a delicatessen. He got a job being a busboy at Joe’s Stone Crab, which was across the street from the apartment we moved into. Which is now a parking lot. When we came back a few years later, we found it torn down.

Leifheit: Tell me about the installations where you recreate pieces of that apartment—the kitchen table and the bedroom. Why do you want to go back to those places?

Pierson: The bedroom piece I made specifically for this show. The building had a central courtyard; it was called the David Court. And we moved in there. I wound up making these pieces about it. There’s another piece that’s the kitchen table. These two installation pieces that I made really early on were based on the setup here.

Leifheit: You were already nostalgic by then.

Pierson: In ’91, ’92—only six years later—I was already like, Those are the best years of my life. I want to see them again.

Leifheit: What made that time in Miami so good?

Pierson: I had so much fun. I met all these people. My friend Christine who was a social worker. Stewart became my friend, but I met him because he was a client of hers. We wound up taking a trip cross-country. It was not without drama.

Courtesy the artist, Lisson Gallery, and Regan Projects

Leifheit: And these photographs became your first New York show.

Pierson: Yes. These photographs were what comprised, in 1990, my first show ever in New York. It was at Simon Watson. They were just made at a photomat for ten dollars and pinned to the wall with pins. Even though it was 1990, I had taken all these in ’85 and was building my library of images since I graduated from art school and lost all connection to darkrooms.

Leifheit: You went to school for performance art, I remember, but you were trying to be a photographer.

Pierson: I was trying to be a real color photographer. Do you know what I mean?

Leifheit: Who were you looking at then? I know Jason Byron Gavann was an early influence.

Pierson: Mark Morrisroe, for sure. And Diane Arbus, William Eggleston. When I saw Midnight Cowboy, I was like, Oh my God, it’s me and Mark Morrisroe—because Mark Morrisroe walked with a limp and he was dark-haired, and I was at that time trying hard to give a western cowboy sort of thing. And, of course, the last scene of that movie is where they arrive in Miami on the bus and Dustin Hoffman’s character is dead. I was just finding my way. I didn’t ever think of myself as a photographer with a capital P, but I thought it was a possibility. I was trying to take “good pictures.”

Leifheit: I remember you telling me something about your self-portraits, where you said something like, “I know it’s one of that series when it looks like an image I’ve already seen before.” Am I wildly misquoting you? You’re interested in archetypes or something.

Pierson: Yeah. A fancy curator said, “Genre photography.” I don’t think of it like that. I think of it like, This looks like a ’50s movie-star picture, but I took it. It flawlessly recreates like—

Leifheit: Tab Hunter.

Pierson: Yeah. Or something like that. And I took it in ten years ago. So this one’s more recent.

Leifheit: There are later works in the show that aren’t from that time.

Pierson: Exactly. Later in the ’80s I started shooting for Honcho and other porn magazines. When I took these pictures, it was the same feeling—like, Oh my God. It’s an iconic American blond. I’ve done it.

Courtesy The Bass

Leifheit: Do you think there’s any relationship between that and the way that gay people sometimes really attach themselves to pop music, or these things that are kind of culturally shared normalcies?

Pierson: What do you mean?

Leifheit: Or maybe another way to think about it is like clone culture, where people really latched on to these emblems of mainstream society and used them as a way of camouflaging or creating a new language where people in the same community could recognize each other. And I wonder if there’s something similar about wanting to make types of photography that look like an American stock man.

Pierson: Maybe. I don’t know if it’s a difference between artistic and cultural.

Leifheit: Well, you participate in a cultural level because, in my understanding, you do a certain amount of commercial work. Don’t you do the underwear boxes for Calvin Klein?

Pierson: Not consistently.

Leifheit: I’ve always thought that was kind of powerful, though, because I think some of my earliest self-realizations occurred in the underwear section looking at these generic packages. And I do feel like infiltrating culture on that level, where you’re producing images that don’t exist in an art context, and having them be subversive is hard.

Pierson: I always say yes to magazines because it gets out there. A stack of magazines could hang out in somebody’s attic for forty years, like they did when I was a teenager.

Leifheit: Were you looking at Photoplay?

Pierson: When I was a teenager? Yeah. All that stuff.

Leifheit: I mean, I also like the kind of idea that those boxes end up discarded or those magazines end up discarded, and there’s a certain amount of—

Pierson: Nobody thinks about it.

Courtesy The Bass

Leifheit: How do you feel about trash? It seems like in certain instances, you are using things that are trash, or you’re reusing your own images after they have been run through the mill of culture and then lifting them back up again.

Pierson: Or boxes that should by every means be thrown out.

Leifheit: Yeah, tell me about that.

Pierson: I can’t let go, and because it still seems like good shit to me. And Kodak, what could be more Americana?

Leifheit: And George Eastman was maybe queer too.

Pierson: Oh, I didn’t even know that.

Leifheit: Well, he was a “confirmed bachelor.” But I think there is something that makes me think of that thing you were saying in your talk with Klaus Biesenbach about finding these objects at flea markets on Second Avenue in the late ’80s, old records and pictures of Joan Crawford, that had clearly come from the apartments of gay men who were dying of AIDS. There’s something about when things are divorced from their emotional significance to people and become trash that I always find to be a little bit, I don’t know, sweet and sad and moving.

Pierson: There’s built-in pathos, which is also known as cheap sentiment. Which—

Leifheit: Is like the language of my people.

Pierson: Which is the language of our people, but it is not the language of the art world. That’s why even photography is a second-class citizen.

Leifheit: I’m hoping it’s cyclical and we’re just in a moment where people are not interested.

Pierson: Photography entered sanctified or sanctioned spaces in the ’90s through people like Cindy Sherman, Richard Prince, Nan Goldin—

Leifheit: David Hockney.

Pierson: Now everybody’s a photographer with a phone, so it feels cheap again. That’s why these things started occurring in my practice. In an array like this one, you can see all of it at one time, as opposed to editing a video where it goes by fast. I’m showing you different types of color printing. Color Xerox was a moment we had. I personally think that’s as good as any color print, and it’s a color Xerox.

Courtesy The Bass

Leifheit: You can see a history of photographic processes, and it engages time in a way that is hard to do in a single image. So this time in Miami had lived in your mind as utopian, in some way. And how does it fit into what more has happened since then? I’m curious to talk about the installation of the bedroom.

Pierson: I wanted to do it back then, but beds were everywhere in art in 1992—Robert Gober, Felix, Nan. So I didn’t. Thirty years later, I could.

Leifheit: Was it built from memory?

Pierson: Just from memory. I tried to be offhand about it. At the time I was obsessed with jails and serial killers. I wanted it to look like artwork a serial killer would make. Everything had to be useful.

Courtesy The Bass

Leifheit: One of the main cultural contributions of gay people is in the realm of interior decorating and that those rooms so rarely get preserved. I mean, I think there are amazing artists who are people who make a beautiful home, and that is their work. That kind of art is almost never institutionalized. Were these interiors important to you in that way where they were life as art? Or is it only in recreating them for the gallery that the artwork happens?

Pierson: I think they were art at the time, but I would never have said that. It becomes lodged in your mind, and you want to revisit it. I have done a number of installations of stages, like this one [moves to another room with blue lighting and a small, checkered linoleum stage in the corner]. I spent years standing in nightclubs at one in the morning, looking at an empty stage and thinking, That’s what I call art.

Leifheit: And what about this giant image of a hunk that is next to it?

Pierson: That’s my present to myself for finishing the show. It feels like bathhouse decoration from the ’70s. I love it. I like this picture, because again, it’s like . . . I don’t know. It looks like from a book of matches, from a gay nightclub or something, or the ad in a gay-bar rag. Something from Milwaukee that would say “Pegasus.” And I love the look in his eyes. I still think it’s an incredibly hot, generic picture. I think it’s very sexy. And so I love the fact that it’s this big in my museum show for no other reason than it gives me a kick and it makes sense of this whole room.

Courtesy The Bass

Leifheit: You’ve rephotographed your own ephemera. A re-scan of one of your older pictures in publication is enlarged to almost billboard proportions.

Pierson: That came after my mother died. She had boxes of my clippings. So I scanned them and made them big. This is the first time I was ever in print—Bomb magazine, 1986. There was a moment, probably like ten years ago, when I was anti-photography. There was nothing for me to photograph in my daily life as an old person.

Leifheit: But you don’t feel that way anymore, clearly.

Pierson: Well, my daily life photography is on my phone, and that’s sweet and cute, but—

Leifheit: You don’t think your cell-phone pictures of your daily life today, of your sweet and cute boyfriend and everything, will not one day end up in an array like this?

Pierson: Maybe one day, because photography to me also takes time to cook.

Jack Pierson: The Miami Years is on view at the Bass Museum of Art in South Beach, Miami, through August 9, 2026.