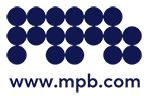

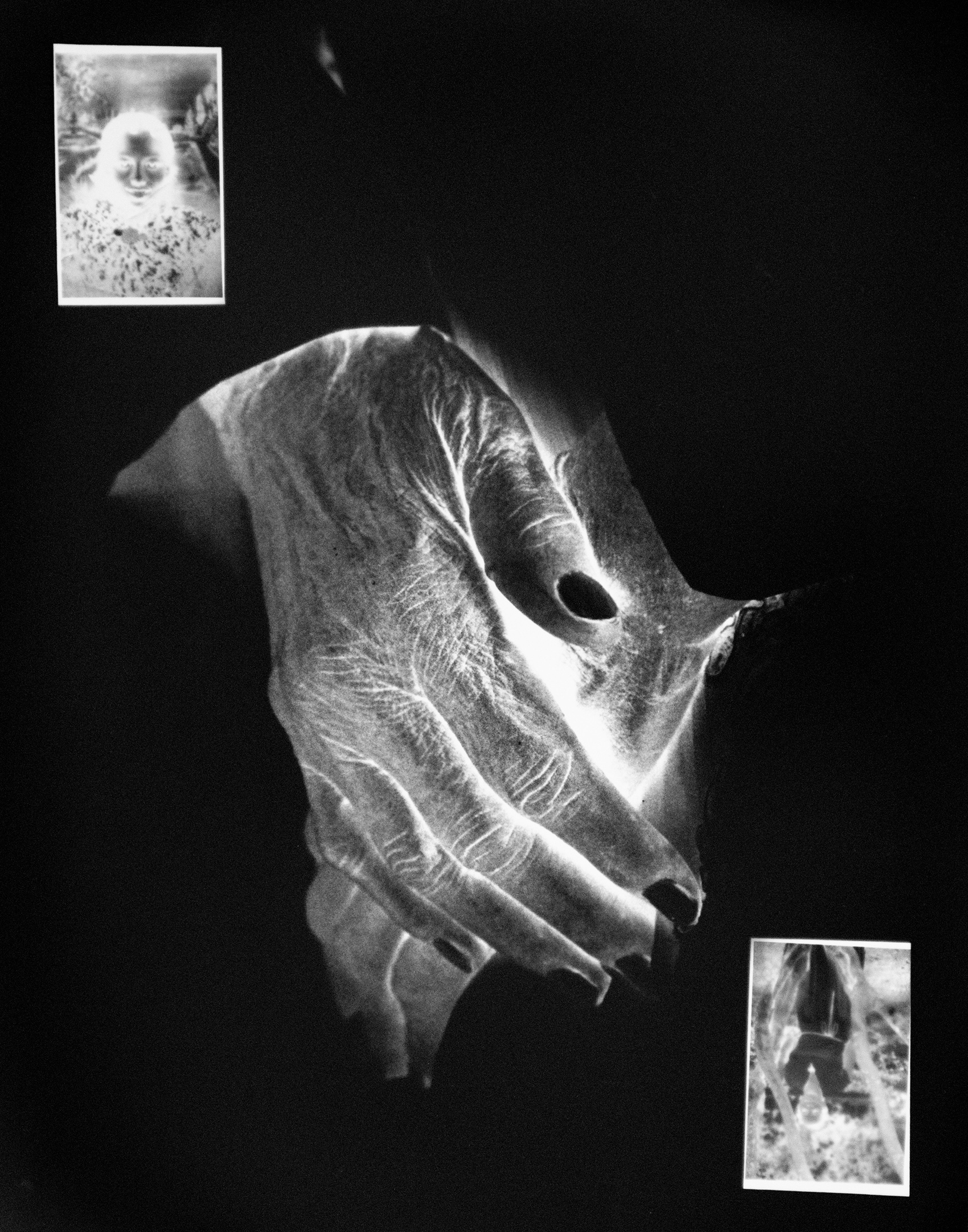

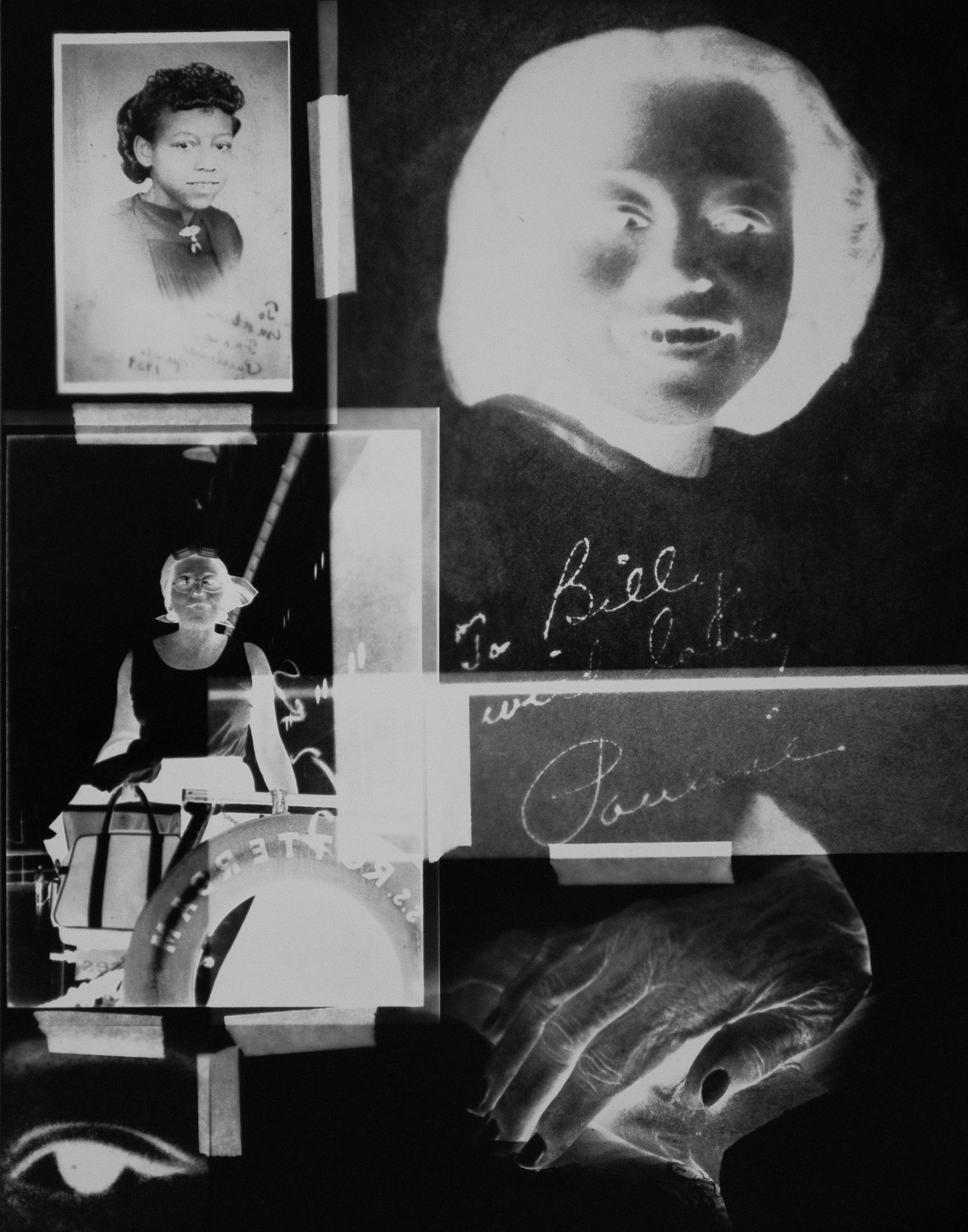

Janna Ireland, Untitled, 2023

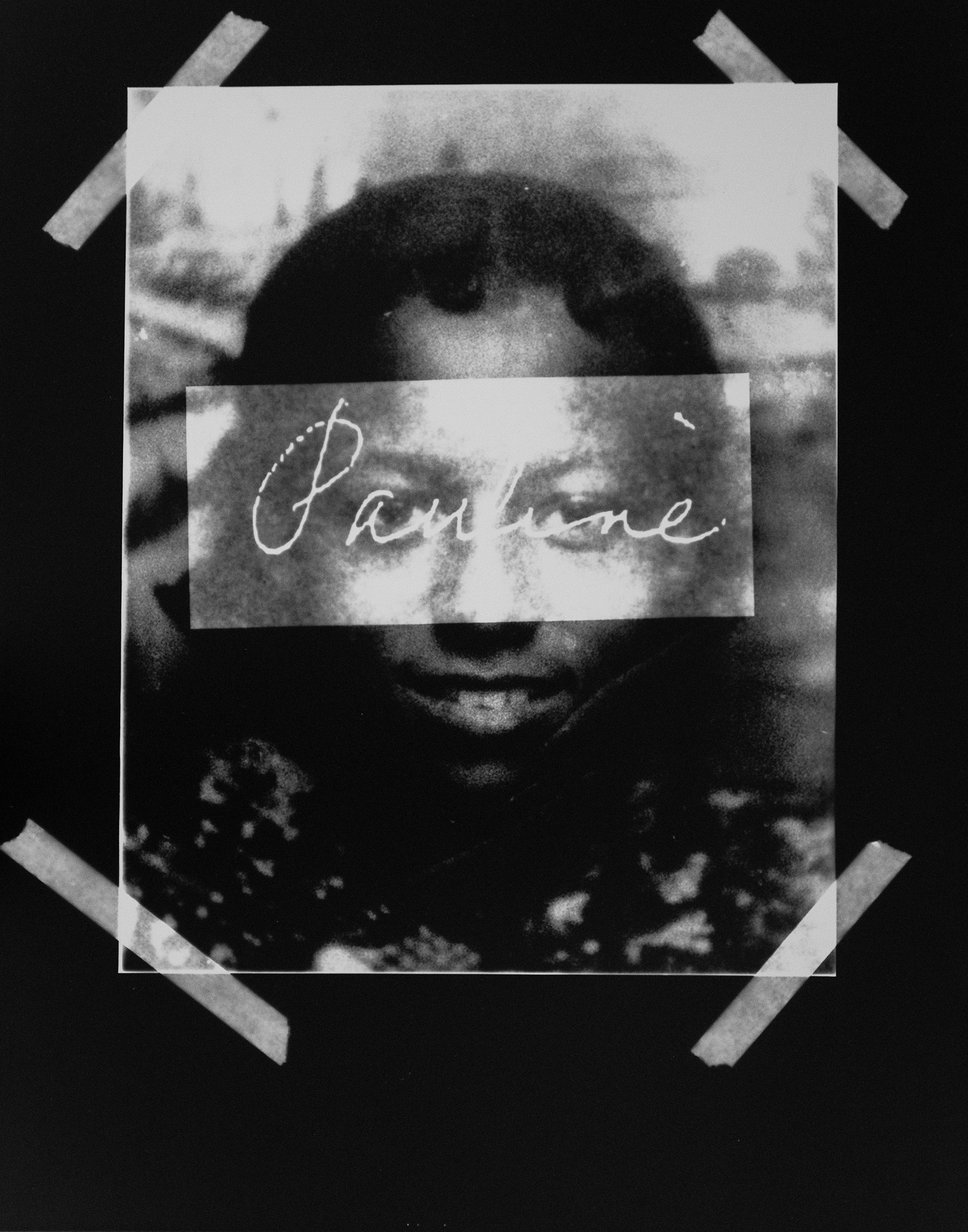

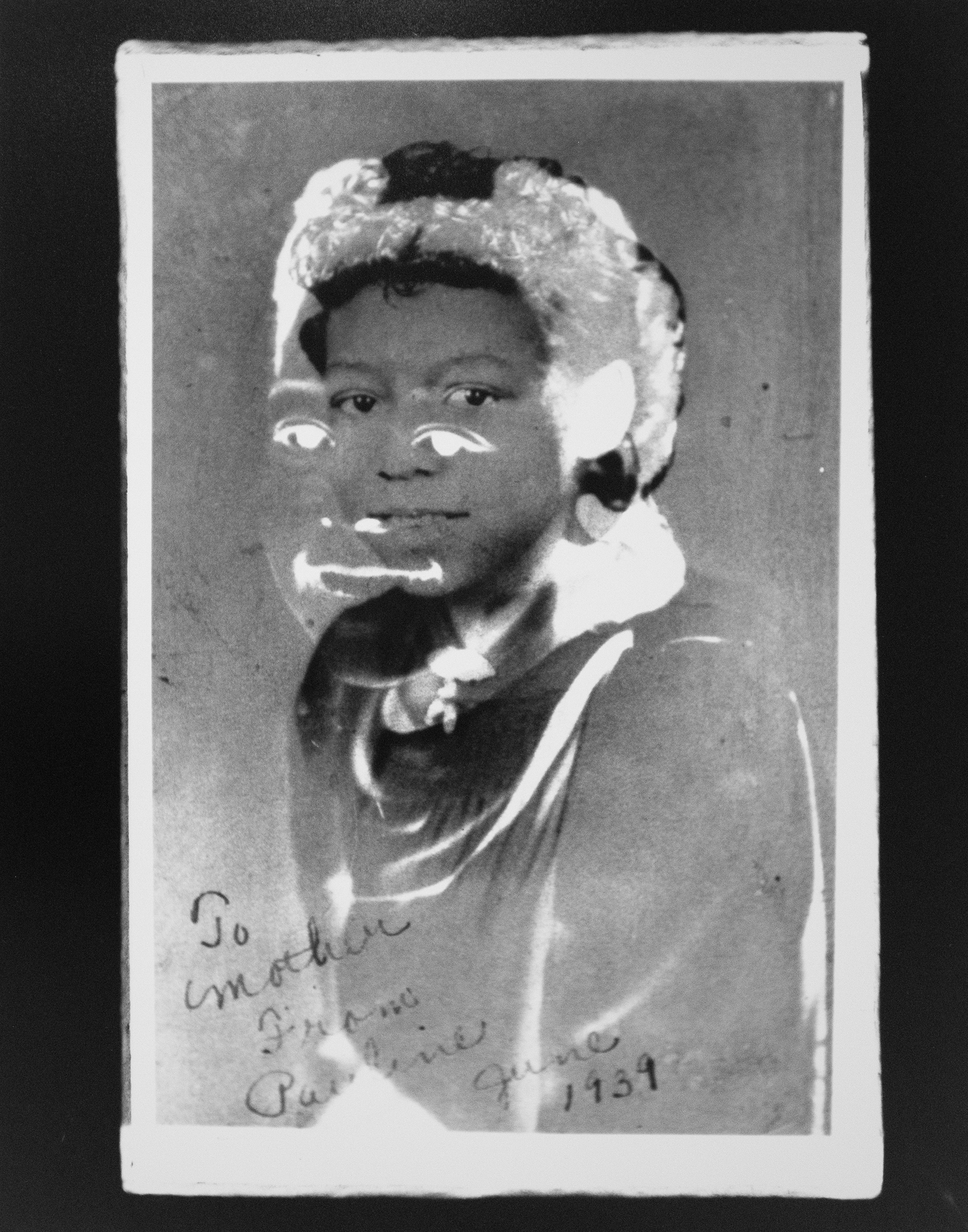

Janna Ireland takes a multifaceted approach in her artistic practice, ranging from architectural photography—such as her critically acclaimed project Regarding Paul R. Williams (2016–2020), which highlights the work of the first certified Black architect west of the Mississippi River—to darkroom experiments. In her series Pauline (2023), Ireland uses the vernacular of the family photo-album to consider the significance of the “amateur” photographer, creating what she describes as “a non-linear tribute to my grandmother.” When the eponymous Pauline died, in 2022, Ireland inherited hundreds of her photographs. The project finds her manipulating some of them in a darkroom, seeing through the images to interpret her grandmother’s lived experience as a teenager in Philadelphia during the 1930s and ’40s. The result is a collection of images that almost seem to be without author.

Born in Philadelphia, Ireland is now based in Los Angeles, where she is an assistant professor in the Department of Art and Art History at Occidental College. She was influenced by her father, a photographer who learned the art form in the Army during the 1960s, and she became an avid collector of vintage photographs, mostly daguerreotype and ambrotype portraits from the nineteenth century. “Something I think about a lot when I look at those photographs is how disconnected they have become from their original source,” she says. “For many years, each one was an important and precious family artifact, but one day, the last person who cared for them died.”

Pauline is as a passport into a past life, visible through moments in time that live on from generation to generation. For Ireland’s grandmother, making photographs and being photographed were radical acts of self-definition and self-preservation. “Framed photographs and family albums are domestic objects that have always fascinated me. It made sense to me to explore family photographs in my work,” Ireland says. In the pivotal essay “In Our Glory: Photography and Black Life,” the author bell hooks describes the relationship between photography and Black image production: “Cameras gave to black folks, irrespective of class, a means by which we could participate fully in the production of images. Hence it is essential that any theoretical discussion of the relationship of black life to the visual, to art making, make photography central.” Woven alongside Ireland’s consideration of the Black experience is a sense of the celebratory nature of deconstructing her grandmother’s archive.

“Pauline is an act of transmutation, taking images that have a special, specific meaning to me and transforming them into something else,” Ireland says. In the process, she combined 35mm enlargements, contact prints, and photograms to create twenty-one different panels that comprise one complete work. Lilies (a symbol of mourning), fragments of her grandmother’s jewelry, and photograms from her funeral were incorporated to memorialize her grandmother’s complex, remarkable life.

Ireland invites viewers to witness the imperfections of her work: the fuzzy quality of duplicated photographs, overlapping edges, and handwriting she’s described as “very left-handed,” illustrating the fondly cherished flaws of family. She says the process was meditative, “day after day manipulating various elements to return to the same images of my grandmother—that felt iconic.” Ireland hopes through her work that the images will live beyond the family photo-album, where others can see and find value in them, just as she has. “They are abstracted versions of the source images, made to be shared, while the originals—in all their specificity—remain private, just for me and my family.”

Courtesy the artist

Janna Ireland is a runner-up for the 2024 Aperture Portfolio Prize, an annual international competition to discover, exhibit, and publish new talents in photography and highlight artists whose work deserves greater recognition.