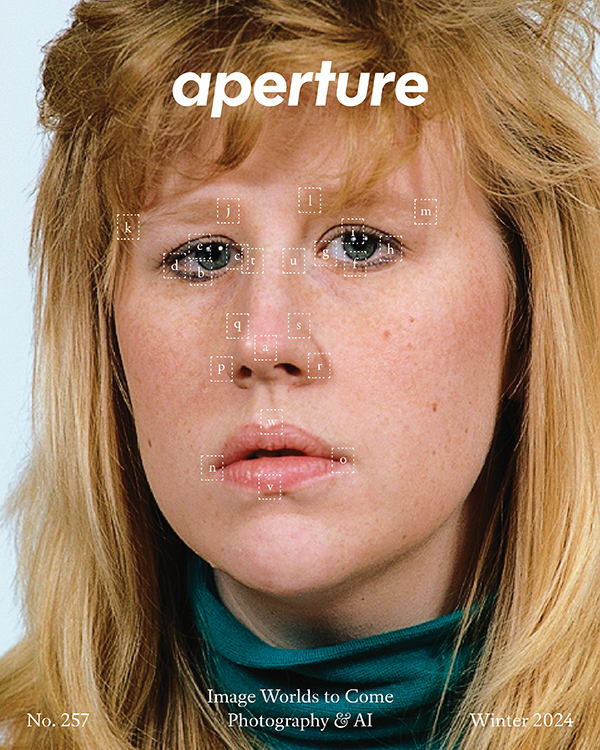

Joan Jonas on Her Special Commission for Venice’s Newest “Pavilion”

The acclaimed multimedia artist speaks about her poetic call to action on behalf of the world’s oceans, the siren call of her long lost Leica, and why Robert Frank and Mary Ellen Mark loom large.

Joan Jonas, Moving Off the Land, 2019, Ocean Space, Chiesa di San Lorenzo, Venice. Performance with Ikue Mori and Francesco Migliaccio. Commissioned by TBA21–Academy

Photograph by Moira Ricci and courtesy Joan Jonas

Joan Jonas, who represented the United States at the Venice Art Biennale just before the last American presidential election season—when science and facts were still a given and a Trump presidency seemed far-fetched—has returned this go-round with a special commission for Venice’s newest “pavilion.” Though Jonas’s new project, entitled Moving Off the Land II (2019), evokes the form of the artist’s acclaimed image-laden, performative, musical, and sound-based installation from 2015, her challenge here was unique. And that’s because the space for which Jonas has designed the new site-specific work has a quite different mission.

Rather than serving one nation’s cultural—and often political—interests, this new venue is meant to represent the interests of the oceans around the globe in the threat of the climate crisis, caused by global warming, ocean acidification, plastics, and other forms of man-made harm. Ocean Space, as it’s called, is international, or transnational, to the core. Housed in the ancient Church of San Lorenzo, right on a canal, Ocean Space is the brainchild of the Swiss-born arts philanthropist Francesca Thyssen-Bornemisza and an outgrowth of the London-based TBA21-Academy, which she co-founded with its director Markus Reymann to foster interdisciplinary projects on marine conservation around the world. Maja Hoffman’s Luma Foundation, another of the most prestigious European contemporary art foundations, has co-produced Jonas’s inaugural presentation.

Ocean Space, Chiesa di San Lorenzo

Photograph by Enrico Fiorese

As a whole, Moving Off the Land II explores how oceans have cross-culturally served as a totemic, spiritual, and ecological touchstone. Presented in nonlinear fashion, the exhibition has video screens tucked into a loose array of different-sized wooden kiosks. I particularly appreciate the ones that are large enough to enter, so that Jonas’s aqueous imagery assumed my whole field of vision. All around the nave of the former church float Jonas’s paintings of marine life and banners with bits of poetry and scientific facts about the world’s oceans and the creatures of every shape and size therein. I spoke with Jonas shortly after the Benniale festivities surrounding her new project.

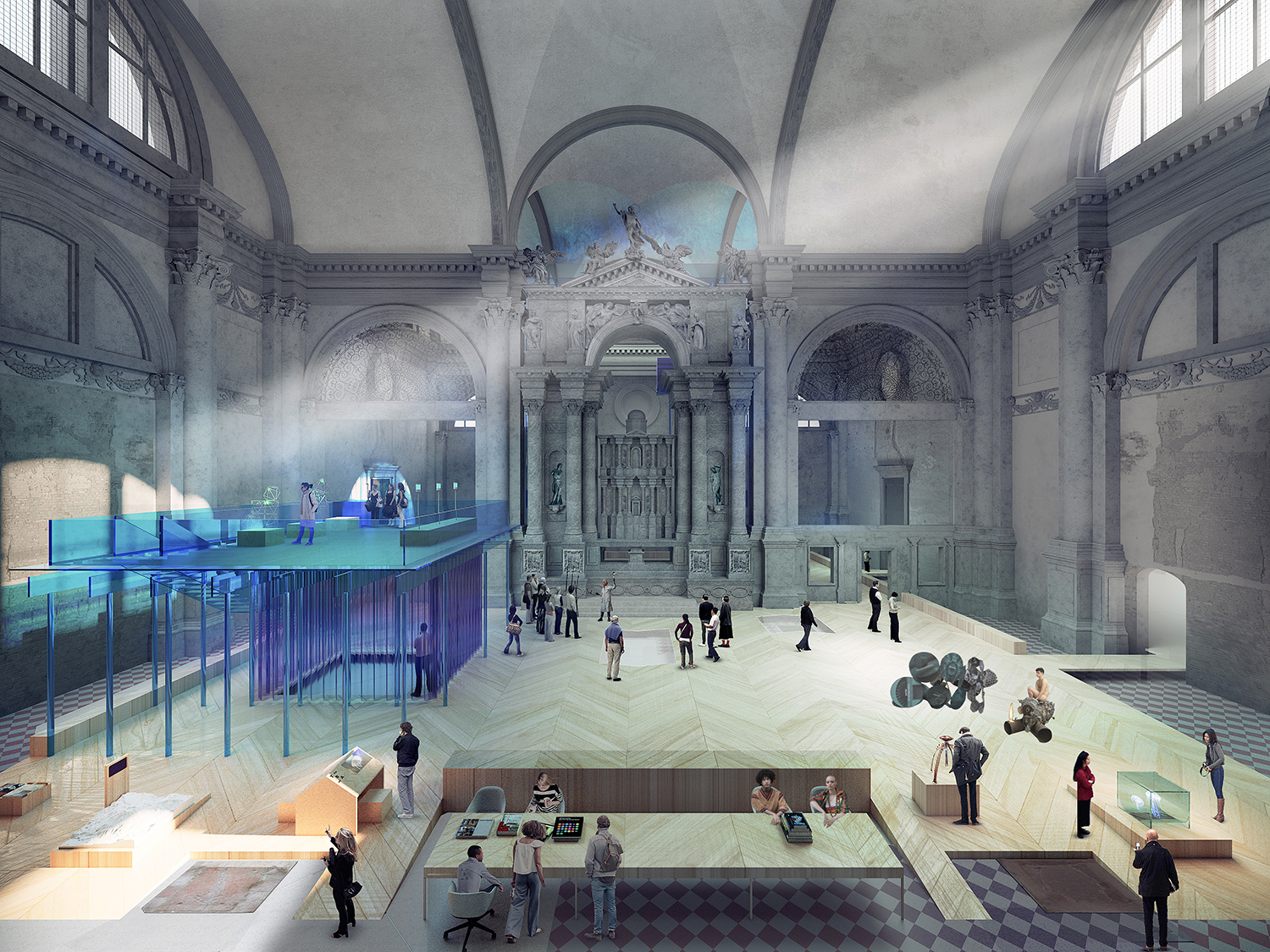

Rendering of Ocean Space, due to be completed in the next three years. Designed by Office for Political Innovation, the first phase of the project opened March 2019

Courtesy Andrés Jaque/Office for Political Innovation

Laura van Straaten: I was struck by your use of underwater footage that was imperfect and murky with algae, sediment, and microscopic life. Were you specifically steering away from beauty shots, and a National Geographic or Jacques Cousteau style of underwater photography that draws attention to the craft of image making?

Joan Jonas: Well, I didn’t even think of going in that direction, actually. I wouldn’t want any like Planet Earth and all that. That’s not my thing. What I’m trying to do is very simple. It’s to show what I find interesting: the miraculous and wonderful nature of all creatures that live in the ocean. And for somebody like me, the most accessible place is the aquarium, which is sort of like a fish zoo, where much of this was shot. I don’t like zoos for animals, but I think it’s the only place that people who don’t dive can see many of these creatures.

Van Straaten: You also used underwater footage that was shot by the marine biologist David Gruber and is in fact quite beautiful, including these incredible almost neon-bright seahorses.

Jonas: I met David Gruber through TBA21. His footage shows some more exotic creatures because of what he studies, which is biofluorescence and how fish perceive the world. So he develops special cameras and lenses in order to film that. I’m interested in perception.

Joan Jonas, Moving Off the Land II, at Ocean Space, Chiesa di San Lorenzo, 2019. Commissioned by TBA21–Academy and co-produced with Luma Foundation

Photograph by Enrico Fiorese

Van Straaten: What was left on the proverbial cutting-room floor when you were mining his archives of footage?

Jonas: I didn’t look at tons of stuff. He sent me some things and then one day, he brought over a whole file. The ones that I chose are all beautiful and fascinating to me—really incredibly beautiful footage of these creatures.

Van Straaten: There’s a nonlinearity, a multiplicity to how you layer images here, where some of the most poignant parts of the Venice exhibition—and the related performances I’ve seen—are when we see you interacting with moving images of underwater creatures not only on the screen behind you, but also projected onto your garments and your face. There are moments where you dance and dart and sway, as if mimicking the movement of the marine life in the swells of the sea. And then in some parts, it’s as if you’re trying to embrace or embody the creatures on the screen behind you—it reads almost as a longing on your part. Can you talk about what you are trying to achieve with your movement in relation to the images behind and quite literally on you?

Jonas: Yes. I’m interested in the surface of the projection. And how do you interrupt that in an interesting way? How do you change the picture? So by bringing other materials in front of an image, and by moving bodies in front of it, that’s one way. This idea of layering—I did it in the piece very elaborately, but it’s the way I’ve been working for a long time. Here, I got more and more into interacting with the fish with my body. It affected me.

Joan Jonas, Moving Off the Land II, at Ocean Space, Chiesa di San Lorenzo, 2019. Commissioned by TBA21–Academy and co-produced with Luma Foundation

Photograph by Enrico Fiorese

Van Straaten: And that visual layering is compounded with the layers of linguistic narrative from various sources.

Jonas: Yes, I read the newspaper and included facts about what’s happening in the ocean and the environment, poems about the ocean, written texts. It’s like a lecture demonstration with me. And I’m juxtaposing one image against another and creating a different narrative by doing so.

Van Straaten: And the still images you used are all pulled from video grabs?

Jonas: Right. I use video because the fish are moving, and I think their movement is so beautiful and works so well with the sound and music.

Van Straaten: Your work has obviously been multimedia for so long—you are a pioneer in video and you employ performance, installation, drawing, painting, music, sound, text, you know, everything you can imagine, but no still photography? What is your stance regarding shooting stills?

Jonas: I don’t have a stance. It’s something that greatly interests me. I’ve always been interested with all of my video projections in the framing device, how to make or alter an image by framing it, just as photographers frame their images. Look at Robert Frank as an example. He sees the everyday and he frames it in a very incredible, beautiful way. So often when I’m working on a piece, I experiment with still imagery and the idea of making a still and framing it. I think that would be the main connection to photography.

Joan Jonas, Moving Off the Land, 2019, Ocean Space, Chiesa di San Lorenzo, Venice. Performance with Ikue Mori and Francesco Migliaccio. Commissioned by TBA21–Academy

Photograph by Moira Ricci and courtesy Joan Jonas

Van Straaten: No camera though?

Jonas: I used to have a Leica a long time ago. In my archives I keep stills that I’ve taken over the years. I almost bought a Leica a few years ago, because I wanted to experiment with digital and analog and work more with stills. I’m very interested in it, and I’m going to return to it probably at some point, in some way. It’s something I’ve thought about a lot for a long time, and I never can get around to it, frankly. And Mary Ellen Mark, who was a friend of mine, was totally enthusiastic about that decision and was actually helping me to buy a new Leica. But, I never followed through.

Van Straaten: Did the mission of TBA21/Ocean Space around the climate crisis make you feel that your image making for this project had to be rooted in documentation?

Jonas: Documentation is just part of my general thinking, part of my language naturally. But I don’t think of it as “I’m going to make this poetic documentary,” like the way Robert Frank works with documentary.

Van Straaten: You mentioned Robert Frank twice now. I understand you were in an early film of his, in 1975?

Jonas: Yes, it was a film called Keep Busy (1975), where there were a group of artists [including Richard Serra] up in Cape Breton. He made it with a man called Rudy Wurlitzer. And we went out on an island and spent like four or five days. There was a lot of improvisation going on. I did some movement. It was funny.

Joan Jonas’s Moving Off the Land II is on view through September 29, 2019 at Ocean Space, Campo San Lorenzo, 30100, Venice, Italy.