How John Baldessari Threw Three Balls in a Straight Line

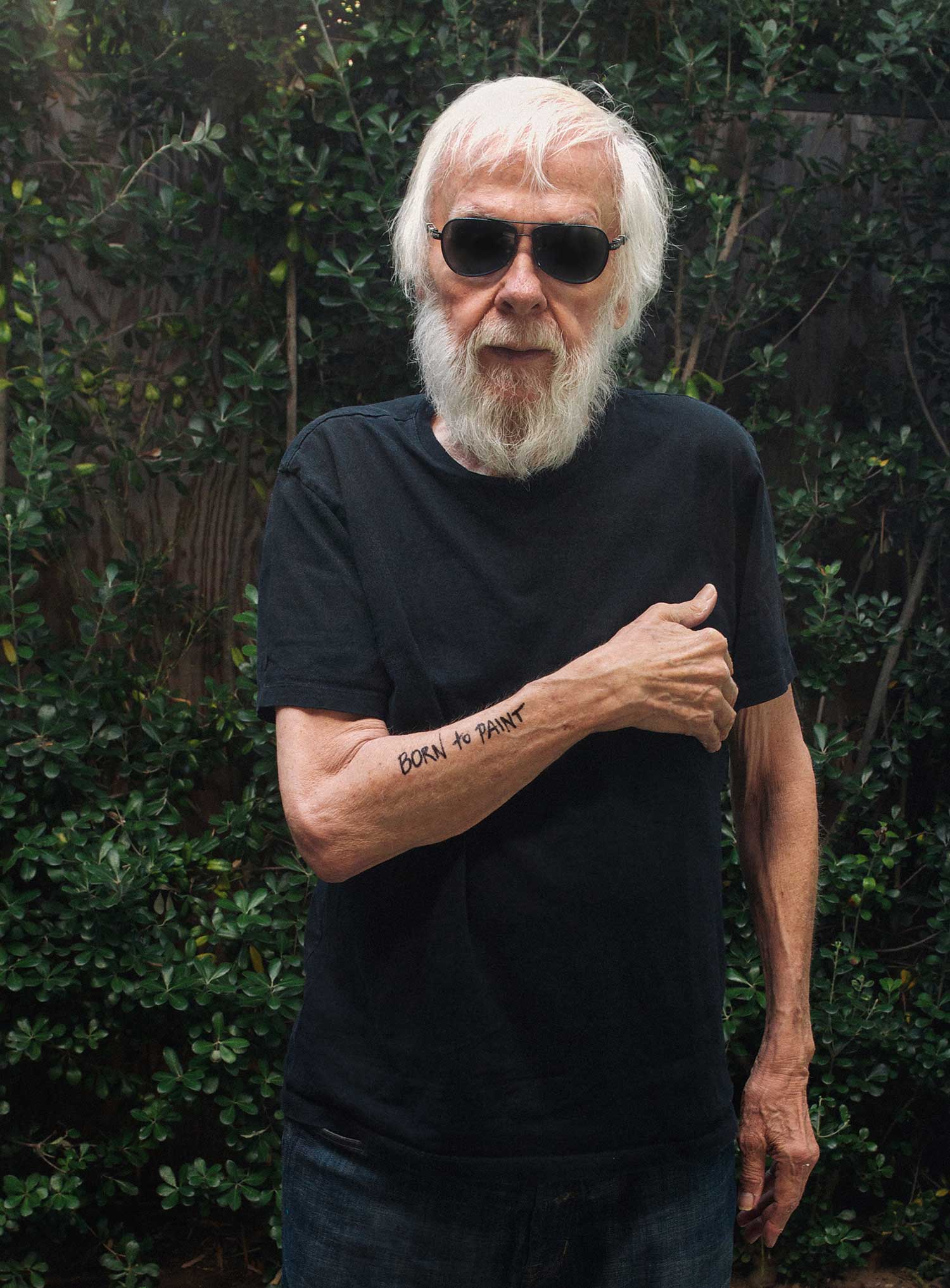

John Baldessari, 2015

Photograph by Molly Berman for Aperture

Ever since the onset of photography, the roles of the hand and the arm in making art have been subject to doubt. Once the definitive means of bringing an idea into form, these human appendages could seem feeble or quaint in an age of science and industry. Allowing gravity to participate in marking became a vital way to give art a deeper or more objective structure. Marcel Duchamp dropped threads to make the lines of his pivotal 1913–14 work 3 Standard Stoppages, and Jackson Pollock later dripped paint to push the limits of his control over line. These tactics called attention to art making as a performative grappling with chance and indifference.

In his 1973 series Throwing Three Balls in the Air to Get a Straight Line (Best of Thirty-Six Attempts), John Baldessari brought his impish wit to this modernist turn. He threw three balls in the air in hopes that a snapshot might catch them aloft and aligned. Through the magic of photography, gravity was defeated, and the balls never had to come down. Although he playfully inserted his arm or his finger in other works, in Throwing Three Balls he kept himself out of the frame. Well, not quite: his balls were in the frame, and the playful reference they make both to his surname and to masculine anatomy is crucial. Throwing Three Balls spoofs the swagger of the Pollock myth of a man laying himself bare through his struggle with the elements. Whereas Pollock orbited his canvases on the floor with all the gravitas of a seminal creator, Baldessari sent his tiny planets skyward with a playful toss.

We should remember, however, that Throwing Three Balls was a game for two players. While Baldessari threw, his then-wife Carol Wixom operated the camera. Chance became the intersection of their performances, where the scattershot and the snapshot met. Each resulting image depicted a hanging sculpture made from dime-store materials that invoked, in the deadpan innocence of pop, both the lofty aspirations of the moon-shot era and the absurd randomness of the atomic age. As the catalyst of such images, Baldessari’s arm became one of the most disarming of his generation.

This article was originally published in Aperture issue 221, “Performance.”