Judith Joy Ross’s Timeless and Empathic Portraits

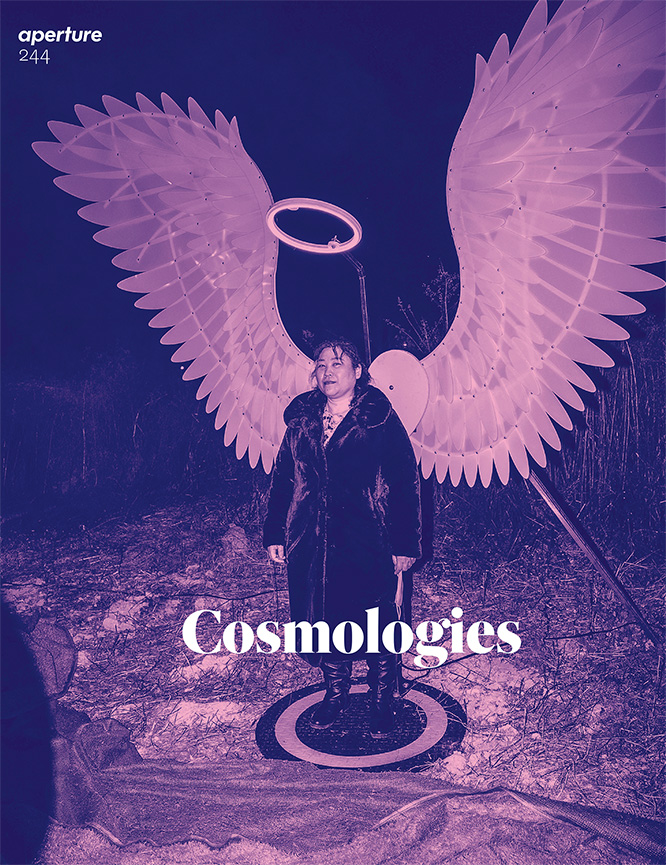

Ross has been called one of the greatest portrait photographers in the history of the medium. As a long-overdue retrospective opens in Europe, a new generation will witness her radical belief in the individual.

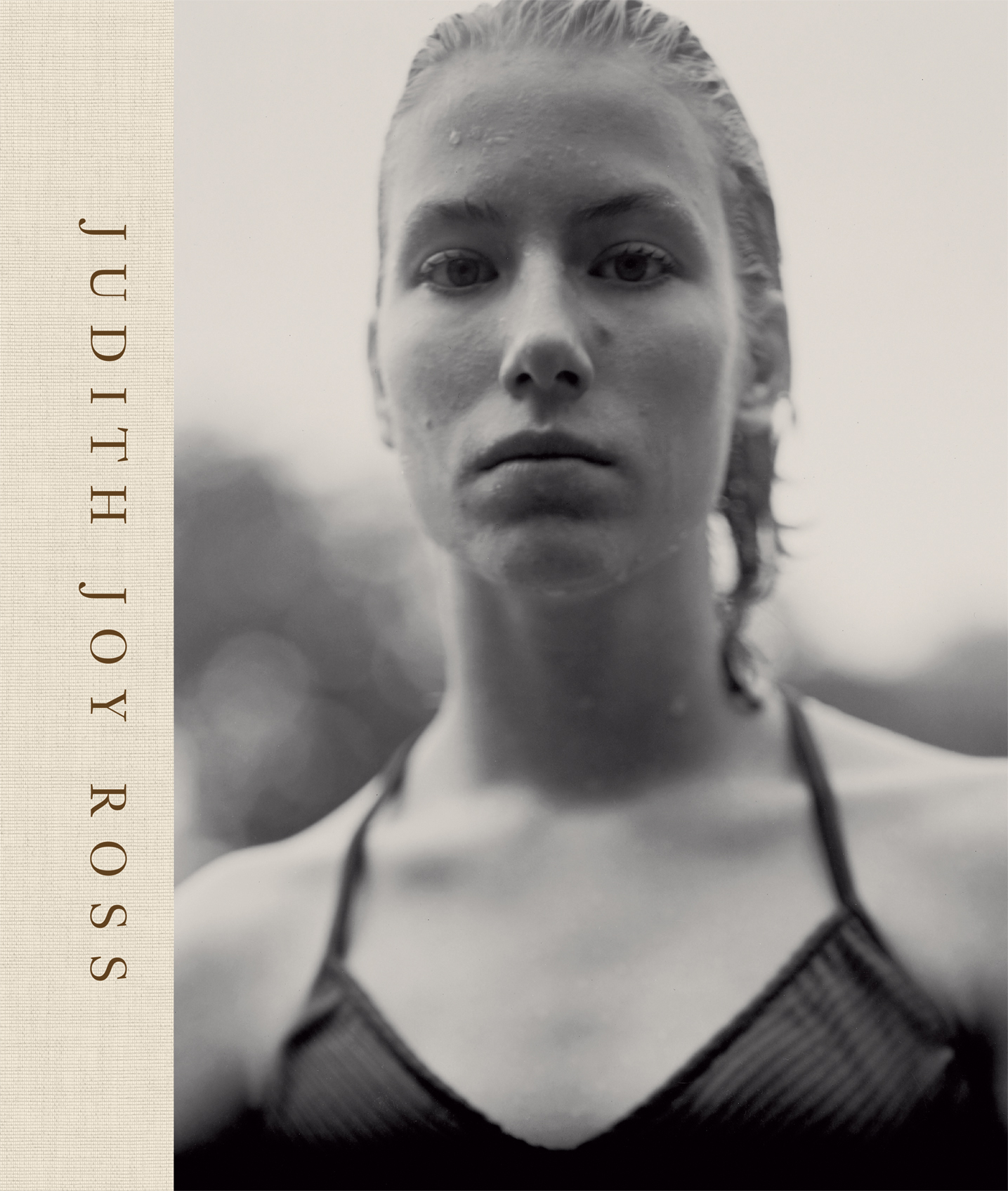

Judith Joy Ross, Eurana Park, Weatherly, Pennsylvania, 1982

Judith Joy Ross wants to show me her garden. As she throws open the back door to her home in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, a large brown rabbit flashes across the yard, a comet trail vanishing into a maze of plants vivid and green against the gray sky. Ross turns to me, her face bright with excitement, “Did you see that?” I am reminded of a story I had heard, how once, while driving in rural Pennsylvania, Ross had seen something in a kid’s face that caused her to pull the car over abruptly, drag her 8-by-10 camera out of the car, and call after two boys, aged twelve or so. Within moments, as Ross disappeared under the cloth and the boys began to arrange themselves before her lens, the alchemy of their connection became palpable.

Those particular photographs did not materialize—there was a problem with the film that day—but the Judith Joy Ross pictures that do survive are the representation of thousands of such lightning encounters dating back to the late 1970s and first widely introduced at the 1985 New Photography exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Ross is a master of the formal portrait, exquisitely executed with astonishing emotional clarity, as if she could see straight into the innermost lives of the earnest schoolchildren and tormented teenagers, the ennobled gas station attendants and car rental reps, along with veterans, senators, mourners, and protesters, most of them in the United States, most of them not far from Hazleton, Pennsylvania, the former coal-mining town where she was born and raised. These people form her photographic universe. “She has this extraordinary antenna,” former MoMA curator Susan Kismaric, who has worked closely with Ross over the years, told me recently. Kismaric was along for the ride when Ross was photographing in Minersville. “Judith never projects, she never condescends or judges, but she intuits.”

In person, Ross is gentle, emphatically honest, devastatingly funny, frequently cursing—all at once. White blunt-cut bangs frame her face; she wears glasses in an outdated prescription. She rarely is idle for long, but when a thought overtakes her, she is apt to rest her entire head in her hands to fully consider it. She greets me on the porch of her yellow house, which, much to her dismay, overlooks construction that will soon obscure her view of Bethlehem, where she has lived for more than half her life. Inside is a home wholly devoted to photography, from the darkroom in the basement to the archives in the attic. “I long for two thousand square feet to store all this shit,” she says. There is a large computer monitor in the dining room; its table holds recent contact prints. For her major retrospective, set to open in September at Fundación Mapfre, in Madrid, and travel through Europe, custom photographic paper was made to replace the now discontinued printing-out-paper Ross relied on for years.

In the early 1980s, when photographers could simply show up in person on an appointed day at MoMA and drop off their portfolios for review, Ross was called in to speak with John Szarkowski, the photography department’s director, who, looking at her first major series, Eurana Park (1982), asked if she knew the pictures of the German photographer August Sander. Ross lied and said she didn’t. “I was like Judas denying Christ,” she says. “I didn’t want him to think I was cheating.” Szarkowski, who bought two of the pictures, offered reassurance: “It’s okay, Judith. It’s called tradition to be influenced by another’s work.” She had, in fact, studied Sander’s pictures closely—how he photographed straightforwardly, centering the person in the frame. Sander’s monumental series Menschen des 20 Jahrhunderts (People of the 20th Century), begun in the 1920s and proceeding for decades, identified and grouped subjects by occupation and social class. Ross isn’t nearly as taxonomic; she is guided by a rapt, intense, wholehearted belief in the individual. (Ross disputes that Sander categorized people.) Her idiosyncratic printing practice—contact prints on printing-out-paper that are then toned with gold— enhances the fundamental uniqueness of the individuals she encounters. “No two prints by Judith are the same,” says Joshua Chuang, who is curating Ross’s retrospective and editing the accompanying catalogue. “Her way of experiencing humanity is through photography.”

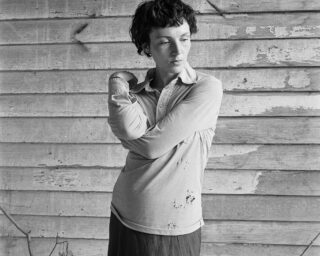

When she was coming up, Ross entered a world dominated by the iconographic portraits of Richard Avedon, Irving Penn, and Diane Arbus, pictures often first published in magazines, where they had to leap off the page. Ross’s work, in a range of subtler tones, operates differently. Her contact prints are almost never bigger than the 8-by-10 dimensions of the negative. To enlarge them, she believes, could be “exploitive.” Of the prints’ scale and intimacy, Ross says, “They are asking you to come closer, and say hi.”

“Like Diane Arbus and like Lisette Model, Arbus’s teacher, she is working with the idea of the self, the tension between who one is and who one projects to the world,” Kismaric explains. “With Arbus, one still sees something of that struggle; in Judith’s pictures, outside the cosmopolitan world, it feels as though they’re working against futures that were prescribed for them. The questions become more complicated.”

Just as complicated is the question of why a photographer so revered by other photographers remains, to an extent, under the radar. The photographer An-My Lê once recalled how, when Ross visited her in New York, she’d play a game of guessing who on the subway Ross would choose to photograph; the fact that she was always wrong cemented Lê’s awareness of Ross’s empathic intuition. “Her work is beautiful in its transparency,” Robert Adams writes in his book Why People Photograph—it’s “a record of compassion.” Gregory Halpern, a photographer who teaches at the Rochester Institute of Technology, has called her “the greatest portrait photographer to have ever worked in the medium.” The photographer Paul Graham, who has taught with Ross at Yale, fell first for her Vietnam Veterans Memorial pictures. “It’s one of the dirty little secrets of photography,” he told me recently. “People act like they want to photograph rocks and houses and trees but what they really want is to have the gumption to photograph people the way Judith does.”

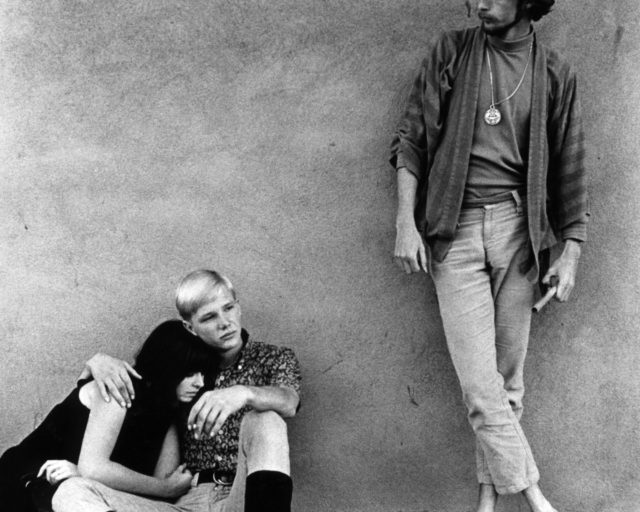

Ross’s pictures are holy in their awkwardness—the teen with the dark gothic bangs wielding a rake, the way the girls clasp their hands over their bathing suits.

Photobooks dominate Ross’s shelves along with images by friends, such as Chris Killip, who died in October 2020. “I can’t understand how his pictures can be so beautiful,” she exclaims. “Tiny little people shown this big, yet every one of them is seen as an individual! Such humanity. Oh, my God. He is missed.” Cabinets in nearly every room are filled with boxes of prints and negatives. To a visitor, the house can feel like the brain’s memory chambers. Ross claims her own memory is foggy, but whenever a gap emerges, she herds me upstairs to look through the cabinets of boxes of prints to supply the story.

Above her dresser, framed works by her heroes mingle with family pictures. “That’s our summer home, where my heart is,” she says, pointing at a photograph of a cabin in the borough of Weatherly, Pennsylvania, where Ross grew up daydreaming and playing with her brothers among the creatures in the woods. “That’s my mom, that’s my dad, that’s my Atget,” she says, pointing out a print of the Panthéon, a revered gift from her brother Edward. The influence of the French photographer is evident in a few of Ross’s early personal pictures: One of her mother, a piano teacher, shown in profile, “looking with some sadness at jewelry at the Met,” on a trip she and Ross had taken to New York. One of her father, reclining on a forest floor, dressed in a suit, appears romantic and elegiac. “Fucking suit and a tie in the woods!” Ross says, laughing. It could have been made after a day at the five-and-dime store he owned in Nanticoke, a former mining town where other relatives also had shops selling candy and secondhand books. “He used to let me help out, paint faces on the mannequins,” she recalls. “I’d put eyeliner on them; I made them even worse. But he never minded. He just wanted us nearby.”

Ross made her first photographs in the mid-1960s as a student at Moore College of Art and Design, in Philadelphia. At the IIT Institute of Design, in Chicago, where she earned an MA in photography in 1970, she felt disconnected from Aaron Siskind’s experimental-minded program. “I was lost,” she says. “Eventually, I didn’t go to class. Including the Literature of Alienation. I should have gotten at least a C because I never went. I mean, what’s wrong with these people!” The lost feeling lingered for a decade. Ross went to Bethlehem, where she taught at Moravian College, simultaneously giving herself the photography education she felt she never received in school, via Eastman Kodak materials and the exhibitions she’d see (Arbus and Bruce Davidson, among others) and books she’d buy (Sander, Atget, Lewis Hine) in New York, two hours away. Eventually, she began photographing again.

In 1982, the devastation she felt over her father’s death carried her back in time. The beloved summer cabin was lonesome in his absence. Ross took her recently purchased 8-by-10 view camera a few miles away, to a public swimming park in Weatherly. In her mind, the children and teenagers she met there at Eurana Park represented a time of innocence before the first experience of grief. The pictures are holy in their awkwardness—the teen with the dark gothic bangs wielding a rake, the way the girls clasp their hands over their bathing suits—barely visible surroundings briefly lifting them out of their lives. In some, droplets of water can still be seen on skin, evidence of how quickly Ross must have forged these connections.

“I photographed people from the get-go. Even though I didn’t know how to have them in my life. That’s probably why I’m good at it,” Ross says. “Something happens, I see them intensely, and we never see each other again. I know it’s just a photograph. I know I’m being delusional. But I like to think I’m capturing the real thing.”

“But if you didn’t think that it was the real thing in the moment, could you even make the picture?” I ask. Ross shakes her head emphatically, no.

Over the years, the arc of her work has expanded in scope to wider communities, public institutions, and national politics, projects for which Ross has sometimes earnestly sought the permission of mayors and civic organizations. But the true subject is both as simple and complicated as every human she meets. In 1983, thinking she would do a series about the United States and the Vietnam War, she traveled to Maya Lin’s granite memorial in Washington, D.C., and found herself drawn to solitary expressions of grief.

The distinctions between her projects became apparent in her printing techniques. “In Eurana Park, certain browns were happy,” Ross says. “When kids were pubescent they turned gray. For me, I didn’t get puberty. I wasn’t a happy camper with sexuality.” Tones for Ross exist on a psychological register, darkening or morphing over time. “Certainly Vietnam was gray. And the gray got so extreme. Pictures from Nanticoke, they might be an exquisite gray with a dash of purple in it that was melancholy. Or a brown shadow on a gray print. A gray print means something.”

In 1986, armed with a Guggenheim grant, one good suit, a makeshift shopping cart for her equipment, including a suspicious- looking box swathed in duct tape to hold her camera, and an inborn fear of authority figures, Ross set out for Capitol Hill—“gray with highlights and a hint of brown in the shadow.” She photographed Strom Thurmond “with his five-foot-tall shoulders and shrunken apple head, surrounded by his French furniture. . . . This awful racist person but I was seduced by his presence.” Her skill at creating instantaneous connections, and the magic ritual of bringing out the view camera, were crucial in these fifteen-minute appointments. In the faces of the members of Congress, humanized in Ross’s frame, it is possible to glimpse, briefly, an aspect of their private selves, not far removed from her young swimmers and workers back in Pennsylvania.

In the early 1990s, when money was tight, Ross began cleaning houses. “Does it look like I’d be a good maid?” she joked, waving at her stacks of archival boxes. “I carried superglue with me on the job; I broke everything.” It was in the midst of this time that the photographer John Gossage called to tell her she’d won a Charles Pratt Memorial Award of $25,000. First, she retorted, “How do I know you’re John Gossage?” and then she called the owners of the house she was supposed to clean that day to say she wasn’t coming. “I’m Cinderella! I just got a grant!”

From 1992 through 1994, she returned to the same public schools in Hazleton she’d daydreamed through while growing up. Again, the goal was idealistic. “I wanted people to pay their taxes. I wanted people to care about public education,” Ross says. “I certainly didn’t care about mine. I thought school sucked.” Ross’s Hazleton pictures are singular in their acknowledgment that school can indeed suck, and in their eerily personal portrayal of the vastness and discomfort and yearning and angst of adolescence— the pride of a perfectly brushed mullet or a cascade of sprayed hair. “These are their own selves,” she says. In a print displayed in her front room, a boy stares at the camera through glasses so thick you long to tell him they’ll be considered cool in twenty years. But here, he simply is a high schooler briefly showing his vulnerable self. Ross’s framing preserves this, acting as a protective shell.

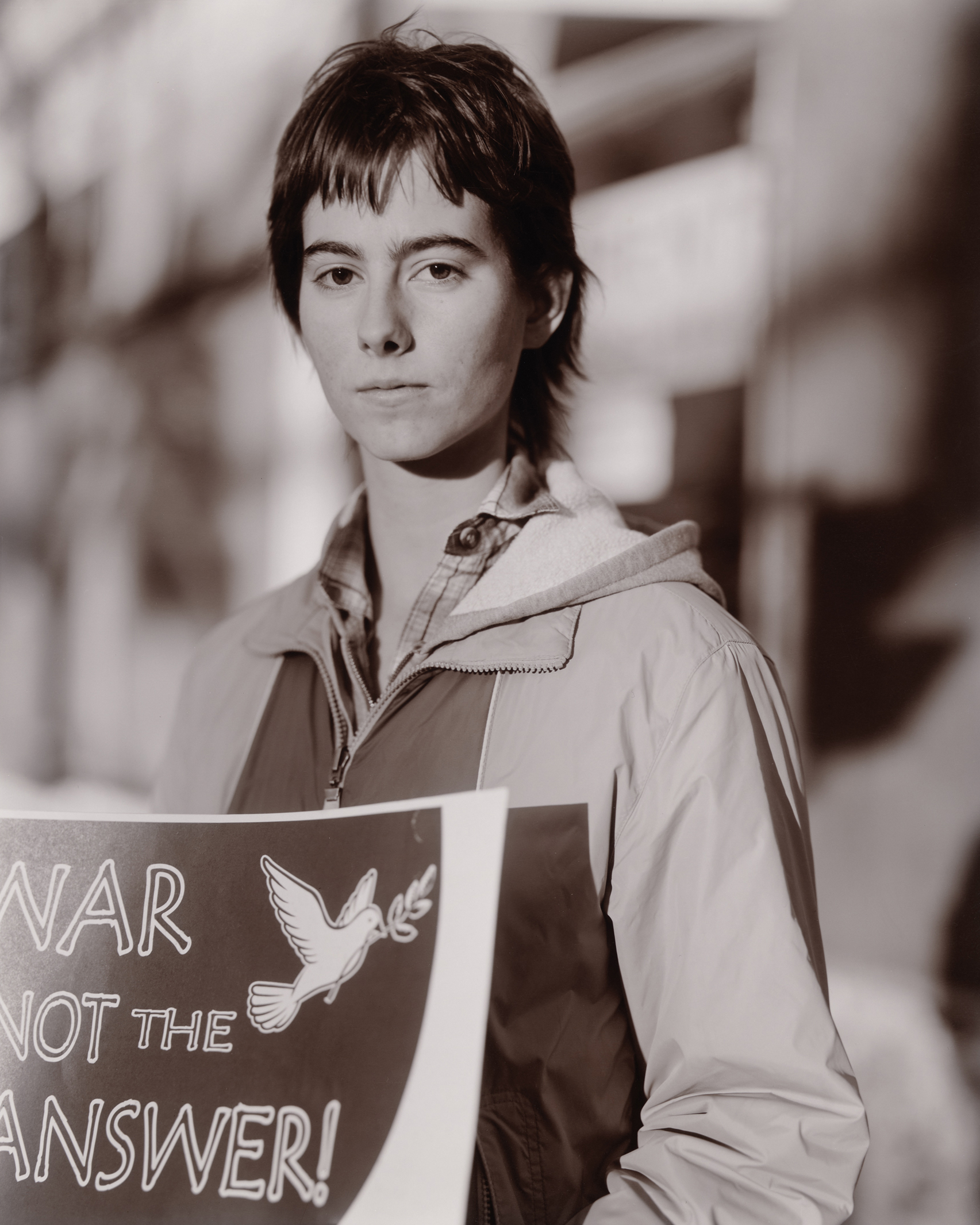

Protest the War (2007), an unassuming little book published by Steidl and Pace/MacGill, her gallery at the time, is about the size of a trucker’s logbook or a horse-racing pamphlet. Ross, hoping the pictures could change people’s minds about who a nonviolent protester is, had wished it would be distributed at gas stations, “right next to the chewing tobacco and the beef jerky and the breath mints.” The fervent, believing expressions of her protesters never made it into this montage, but Ross herself again went to Capitol Hill, hand delivering copies at congressional offices. At the heart of her work is a profound identification with the singular person and a belief in what society can and should be, the rift that exists between the two, and the person confronting the specter of change. “I see you, and, please God, I want to get what I see before it’s gone,” Ross says. “Once you get out the camera, you get discombobulated and you have to find it again. You may not be finding the same thing.”

Ross says she is not interested in photographing people anymore. Or, that she does have a new idea about photographing people that she is intent on pursuing, but she doesn’t want to talk about it yet in a public way. She is recovering from eye surgery that she claims made her vision worse. The world has been so uncertain.

Last year, in the days before the U.S. presidential election was called, Ross began to photograph trees. “Maybe it’s sacrilegious to talk about them this way, but I do see them not as people but as individuals,” she says. We get in Ross’s car, stickered Make America Green Again, and she points out favorite elms as we drive to a cemetery in Bethlehem, from which you can glimpse, through a veil of ropy vines, the cemetery that Walker Evans famously depicted in A Graveyard and Steel Mill in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania (1935). “He couldn’t have photographed from here, because everything’s the same tone,” she notes. Ross comes here for walks, not pictures. “The subject of death is so enormous, who can photograph it?”

All photographs courtesy the artist and Galerie Thomas Zander, Cologne

She is pleased when I notice that, instead of camera equipment packed in her car, an animal cage rests on the backseat. Later, I will think how cage or trap feels like the wrong word, especially for someone who lights up when she describes seeing a muskrat in the wild and tells me she cannot bear to have dogs anymore (“because you love them more than your family, of course”), especially when I learn that it is for the groundhog that lives under her porch and sometimes ventures to the back steps, standing on its hind legs. She speaks of it in a way, I think, that might apply to some of the people in her pictures: “Sometimes, I think I should try to catch it,” Ross says, “and take it to a happier place.”

In September 2001, Ross began to make portraits at another site of mourning—an overlook on the Eagle Rock Reservation in New Jersey where people come to stare toward New York at the spot where the Twin Towers once stood. Silently, Ross would slip a handwritten request to anyone she wished to photograph. A day after our visit, I drive to Eagle Rock. I try to pick out the people whom Ross might approach, and I am sure I am wrong. On my way out, I notice a young couple walking rapidly away from a marshy thicket, carrying a long trap seemingly identical to the one I’d seen in Ross’s car. The cage is empty; whatever they have brought with them, they have now released.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 244, “Cosmologies,” under the title “The World of Judith Joy Ross.”