Ken Pate: Roquette Rockers

Under the theme of “Photography as you don’t know it,” the Pictures section in the Winter 2013 issue of Aperture magazine presents the work of ten photographers who have been overlooked and undervalued. Among these photographers is Ken Pate. The photograph She said…, 1975 by Ken Pate is now available for purchase as part of the Aperture limited-edition print program.

My art history professor was not pleased. “What a waste of your education!” he said, when I told him I planned to write about photography. In France in 1975, photography was not considered a medium of any real importance. I was one of ten photographers and writers who formed a collective to challenge this notion. Our headquarters was a leaky Parisian warehouse on rue de l’Ouest, near Montparnasse, where we met and put out an alternative magazine, Contrejour, as well as books on photography. The magazine (composed of three oversized black-and-white broadsheets) was printed locally and became a success, the European equivalent of Afterimage.

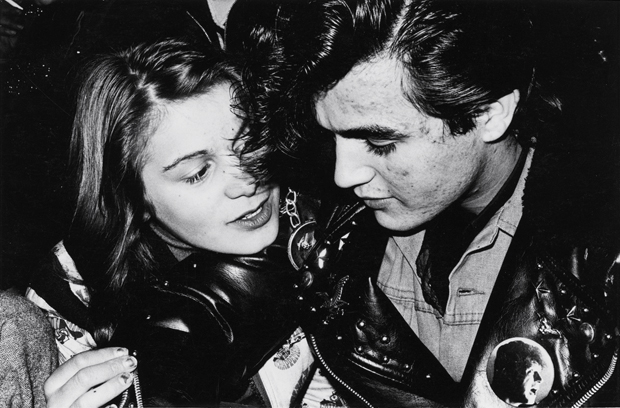

Ken Pate was living at the time across the Seine, in Bastille. A warren of vaults and passages, in the Middle Ages it had been home to a number of “mauvais garçons” (crooks and thieves) who could make an easy escape. Now it was the territory of carpenters and cabinetmakers. Artists discovered its cheap rents, the marché d’Aligre, and the cafes of rue de la Roquette. Pate was a thirty-two-year-old Californian who had moved to Paris a few years before. “I walked the street and pushed my kids’ stroller. I was an habitué of a bar on place de la Bastille, a hangout for soirées for deaf-mutes. The bar got taken over by the blousons noirs, the rockers.”

At the time Pate was photographing ballet and theater to pay his bills. “On my birthday I decided to do something for myself—and then I ran into three of these fellows. I decided to do a book on the blousons noirs. They said sure, do your own thing. I was with them shooting for a few weeks. They were very open, very young, very kind to me. I was a little bit older than them but not very much. I was not judgmental. They were getting together … for mutual affection and protection. I did not have papers and when the cops came it increased the camaraderie.”

How did this relatively unknown photographer find a publisher? “I did not find Contrejour, they found me. The Roquette Rockers wanted prints of themselves to do a small exhibit. I borrowed publisher Claude Nori’s darkroom to do the prints. I was in Avignon when I heard that he was ready to sign a contract. I went to his apartment, we sat around on a mattress on the floor. It was the first book Contrejour did. It sold for fifteen francs at Fnac, a retail shop specializing in books and entertainment…” I wrote the introduction to the book. Contrejour went on to publish 170 books on photographers, including Robert Doisneau, Jacques Henri Lartigue, Anders Petersen, Bernard Plossu, Willy Ronis, Sebãstiao Salgado and Sabine Weiss, until it closed in 1995. Nori restarted the publishing house two years ago. Later on Pate lived in New York for three years, where he drove a taxi by night. Then he came back to France, where he has lived in a small town called Vendôme for seventeen years. What is he doing now as a photographer? “I am taking digital pictures but I am deliberately not on the Web and hard to find.”

When I look at the Roquette Rockers pictures now, the spirit of the era comes back to me: there is a freshness and honesty in the pictures that is missing from most work being made today, as photographers are increasingly self-conscious and self-promoting. The rockers want to look tough, but their youth and naiveté shine through. It is that directness that drew me to the pictures originally, and made me want to write about them. The rockers’ tattoos, hair styles, jewelry, and leather jackets echo those of the British Teddy Boys and Bruce Davidson’s Brooklyn Gang, but these are models that the rockers didn’t know firsthand: they were kids who never traveled and spent all their money on clothes and bikes. Today, Ken Pate’s first and only book is, to his surprise, an object of fascination; for me his pictures still evoke a sharp pleasure, a feeling that is now mixed with a stab of intense nostalgia.