Essays

A Native American Artist’s Prayer for Home

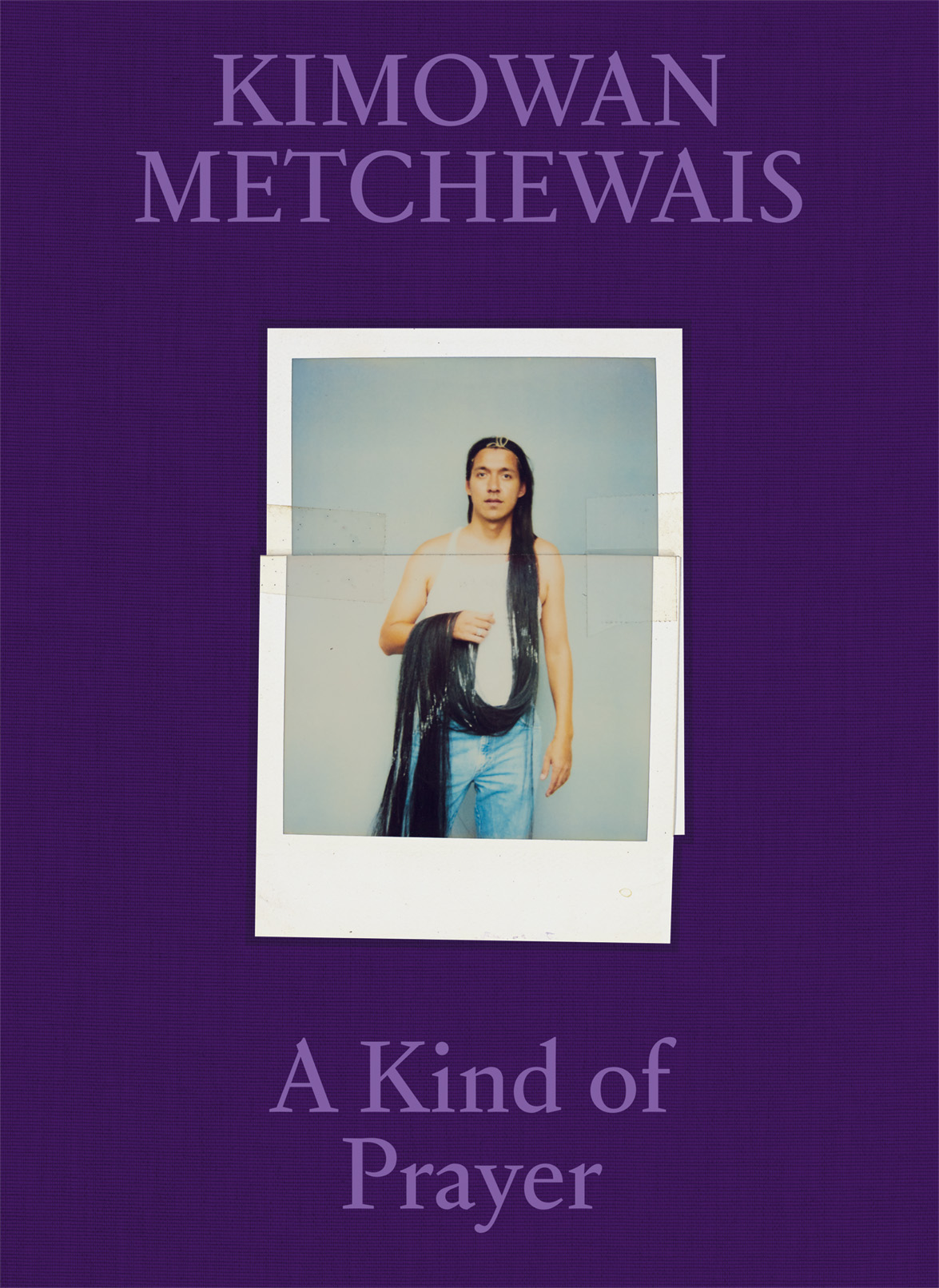

Kimowan Metchewais died at the age of forty-seven, leaving behind ethereal Polaroids and mixed-media works that embrace Indigenous ways of knowing.

An earlier version of this article was originally published in Aperture, fall 2020, “Native America,” and was updated and expanded for Kimowan Metcheswais: A Kind of Prayer (Aperture, 2023).

For the 2002 installation Without Ground, the Cree artist Kimowan Metchewais transferred dozens of small photographic self-portraits to the white walls of the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) at the University of Pennsylvania. The full-length likenesses were posed in the ICA’s Ramp Space, as if they were searching the empty expanse for something hidden from both artist and viewer. By cleverly using scale and gently fading some of the photo transfers, Metchewais, who went by his stepfather’s surname, McLain, at the time, created the illusion of figures receding into space. Treating the walls of the museum as the “ribcage of a living animal,” he felt that his photographs were like “tattoos etched onto the bones of the beast,” anticipating their burial within the institution’s architectural memory, covered by future layers of accumulated paint.

Over a decade later, in 2014, the Omaskêko Cree artist Duane Linklater meticulously scraped away layers of paint from the ICA’s walls, creating stratified craters in search of the installation. The effort to uncover these photographic traces was akin to a search for Metchewais himself, an attempt to connect with the artist who had passed away only a few years earlier, in 2011. The hunt for evidence was forensic, replicating the investigatory nature of Metchewais’s wandering figures. “I think North America is a crime scene,” Metchewais said of Without Ground in 2006. “Something was lost and it needed to be found. The figures were detectives, a search party. I wanted them to be looking for the crime itself. . . . I hate to say it, but what happened to the land and people here was/is a crime. People today don’t see that. They understand it, they know it, but it doesn’t seem to mean that much to them. To me, it means a lot, in many ways.”

Without Ground lacks perspectival space or a defined horizon line, evoking the Pueblo watercolors of the Studio style—which typically favored depicting costumed dancers on neutral grounds—that developed out of the Santa Fe Indian School in the early twentieth century. Metchewais, however, insisted that the land in these paintings was not actually absent but rather “unseen,” a symbolic denial of ground taught to the Studio painters that corresponded with the historic displacement of Indigenous peoples from their ancestral lands. His installation at the ICA was thus about seeking an invisible landscape and the crime behind its loss and continued absence. The white museum wall, rather than a neutral ground, became a site at which to consider the theft of Indigenous land, underscored by the installation’s title, an example of the ways in which Metchewais rearticulates colonial memory through photography. “I am concerned about how people see the landscape of North America,” Metchewais said while speaking about Without Ground. “I want the land to be omniscient.” In this statement lies the breadth of his practice, which moved between perception, representation, and understanding the capacity of the land to sense and speak for itself. His work explores the ground, aesthetic and territorial, on which contemporary Native art and communities might stand, and his images propose a new intellectual space that exceeds the mere subversion of stereotypical representation.

Consider Metchewais’s most lauded work: the Cold Lake series (2004–6). It consists of photographs of children and other community members from the artist’s homeland of Cold Lake First Nations, a Cree and Dene reservation in Alberta, Canada, pictured in the style of straight photography on the street or wading in the namesake Cold Lake. Metchewais returned repeatedly to his home to take thousands of photographs of Indigenous children, who he sought to depict as a youthful and emergent force. These works form the bulk of the sub-series that the artist titled Child Nation. Notes in Metchewais’s sketchbooks from about 2000 also propose what he called “post-Curtis portraits,” works that are empty of ethnographic baggage and instead emote “reclamation” and “a desperate, pathetic attempt to restore” and “elevate human status. It seeks to be heroic. It wants to be owned.”

This label is a reference to and an attempt to move beyond the outsize influence of the photographer Edward Curtis, whose staged and romanticized portraits from the twenty-volume anthropological series The North American Indian (1907–30) have permeated the visual imaginary. The post-Curtis portrait is also about community, place, and belonging. “To be Indian, Inuit,” Metchewais writes, “that is in the heart.” In Young Mothers at Cold Lake (2005), four women gather knee-deep in the water, smiling and laughing together; one looks backward to keep an eye on her children, who are outside the frame. Other images from the series are taken on the streets of Edmonton and at powwows. But the artist’s attention was mainly reserved for creating striking three-quarter length or closely cropped portraits of children in the lake waters.

His most well-known image from the series, Cold Lake Venus (2005), features a young girl facing the camera, hip-deep in water that stretches behind her to meet the sky at the horizon. The photograph is saturated with what Metchewais calls “divine beauty,” which emanates from the girl like the ripples in the lake water. “Look at us emerge. We are beautiful, standing in a magical place, just back from the Wal-Mart [sic],” Metchewais writes of the work. His wry superstore reference dispels the tendency in the popular imagination to take Indigenous communities out of time when romanticizing their ties to the landscape. He succeeds in picturing new image worlds to express a fundamental connection to home and place while evoking Indigenous and Greek creation myths.

Born in 1963, in Oxbow, Saskatchewan, Metchewais adopted his mother’s maiden name in the latter part of his life. He began his career making political cartoons and graphics for Windspeaker, Canada’s most widely distributed Indigenous-content newspaper, before receiving a BFA from the University of Alberta in 1996. His early work tackled the legal and cultural frameworks of Indigenous identity and tribal membership, questioning the means by which identity is defined and challenging the demand, still present today, for Indigenous artists to perform a so-called authentic connection to land, language, and community. His 1989 painting A Guide to Doing Contemporary Indian Art pokes fun at the collage aesthetic prevalent in the work of First Nations contemporary artists in the 1980s, such as George Longfish, Jane Ash Poitras, and Joane Cardinal-Schubert (who was a mentor and purchased the piece). Handwritten penciled text on a red-painted rectangle instructs: “Place images below . . .” “old photographs,” “some modern stuff for contrast,” “syllabics,” “buffalo(s),” “a few tipis,” and so forth.

Metchewais received his MFA from the University of New Mexico (UNM) in 1999. He was attracted by the school’s well-regarded photography and Native American art history programs, and found there a network of Indigenous classmates including Larry McNeil, Will Wilson, and Rosalie Favell. While at UNM he began to rigorously develop the photographic and mixed-media practice he is known for today. He challenged the authority of fixed representation while pursuing answers to the question of authenticity that he asked of himself and his work: “What makes Indian people Indian?” His mixed-media compositions and elaborate photo collages incorporate references to Native art history: winter counts, ledger paper, and parfleche designs juxtaposed with images of urban and natural landscapes in Sandias (1998); portraits of Plains elders mined from archives and popular culture, and those taken with his own lens, in The Origin of Tobacco (2000). His 1999 installation After, first exhibited in his MFA thesis show at UNM’s John Sommers Gallery, featured illusionistic photo transfers depicting birds, insects, and bowls on the gallery walls, a process Metchewais called “photographic gallery tattoos.” It was an antecedent to the later ICA installation Without Ground and exemplified his “search of elegant solutions to challenges of narrative in space.”

Kimowan Metchewais: A Kind of Prayer

75.00

$75.00Add to cart

The Polaroid was core to Metchewais’s process, and while at UNM he began amassing an extensive personal archive, meticulously organized during his lifetime by subject and alphabetized in boxes. He used these photographs as references for his paintings and embedded them in his mixed-media collages and as transfers to large-scale works on paper. He cut up, rearranged, and taped them back together before rephotographing and reentering them into the collection as a shifting and circulating living archive. The tactility of the cut-up photographs, with conspicuous scratches, creases, and Scotch tape fastenings, distinguishes them from digital images, and Metchewais sought to maintain these qualities even when he rephotographed his Polaroids and digitally printed them. He commented at the 2009 conference Visual Sovereignty at the University of California, Davis, that “few things compare to the silky touch of a newly developed print in the palm of one’s hand.” His Polaroids also freed him from a reliance on archival images from outside sources. Instead, Metchewais’s use of personal imagery avoided the need for intervention, interrogation, and reinscription that weighs down some work by contemporary Native photographers who explore museum and institutional archives as sites of privileged access, subjugation, and colonial violence.

Metchewais’s Polaroids contain many series: toy buildings and animals shot in a studio; smokestacks and mountain ranges; flowers, cars, and other quotidian objects. Many are portraits depicting family, friends, classmates, and colleagues, and being from many periods of his life they serve as both an essential precursor to and extension of the deep exploration of community seen in the Cold Lake series. Portraits include his brothers, Hans and Luther; Archie Seelkoke, an Alaska Native man that Metchewais met in Albuquerque; fellow photographer and friend Laena Wilder; and many more faces from his home, his time at UNM, and his later colleagues in North Carolina. These individual portraits are an archive of stories, personalities, and bodies, occasionally cut up, rearranged, and accompanied by biographic annotations in Metchewais’s notebooks.

The artist frequently includes his own body in this archive. In one undated set of Polaroids, he photographed his own hand in a series of gestures, some of which were later modified and digitally printed under the title Indian Handsign. Loosely held poses of fingers and arm recall anatomical studies, while distinct hand shapes suggest a form of sign language. On these Polaroids, Metchewais penciled labels directly below the images: a trigger-finger pose is labeled “GO”; an upward-facing palm is labeled “OPEN.” The hand signs function as study and reference materials while also triangulating a relationship between body, language, and image. The signs do not appear to be based on American Sign Language but rather obliquely reference Plains Sign Talk, a historical sign language used by Indigenous peoples across central North America in trade and oratory. Purported manuals for Plains Indian Sign Language were published throughout the twentieth century, and the language was widely appropriated by the Boy Scouts and other non-Native summer camps and societies. The images also recall the hand signals from the rapidly paced Cree handgame (or “stick game”) that Metchewais played with his uncles on Cold Lake First Nations. Eraser smudges on the Polaroids suggest that Metchewais wrote and rewrote the labels, drafting his own language for this series of universal gestures, countering appropriations with a new baseline of bodily signs. In some instances, he printed multiple photographs on single sheets of paper in three-by-four arrangements of hand gestures, forming a kind of visual dictionary or record.

Metchewais images propose a new intellectual space that exceeds the mere subversion of stereotypical representation.

Metchewais circulated language throughout his work, often in deeply personal ways. Images of his grandmother’s Cree-language Bible recur in his oeuvre, including in works that reproduce its worn leather cover and front matter, namely a page of the Cree syllabic alphabet with French phonetic translations. Metchewais often signed his name Kimowan in Western Cree syllabics, ᑭᒧᐘᐣ, which means “it is raining.” In several versions of his 2004 photo collage Cold Lake, the Cree name for the lake, atakamew-sakihikan, appears in syllabics underneath the English. These works are examples of what he called his “paper walls,” photographs printed on paper sheets taped together into wall-size constructions. Emulating Plains parfleches, Metchewais designed such works to be mobile, foldable into transportable packets that can be tucked under one’s arm as a carry-on until unfurled into nearly room-size installations. They also make clear why Metchewais identified himself not as a photographer but rather as “a sculptor of flat, rectangular objects of various textures and tone.” Some of the pieces of tape are in fact photographic images of paper taped together, such that the simulation of texture blurs reality with representation. The papers were dipped in water colored by rust and tobacco, “baptized,” in the artist’s words, as a ritual act. Because tobacco is a sacred substance among many Indigenous peoples, the material of the work might be considered animate. “Tobacco is a handshake. It signals honesty and honorable intention. Cold Lake is a kind of prayer,” Metchewais said.

That prayer is about home, family, and memory. Cold Lake includes multiple iterations of a scene of Metchewais and his cousin Conrad wading below the long horizon line of the lake. It combines several snapshots taken from shore by the artist’s mother. The photographs are “a record of family love,” binding Metchewais, his family members, and the lake and sky in kinship relations. Given the installation’s wall-size scale, the close viewer becomes wrapped in the experience and memory of that place. These works are less about the recovery or performance of memory than a living relation to the land. They also situate home and place as terms that escape essentialism. In Goodwill, 118 Avenue, Edmonton (2005), Metchewais captured a scene of furniture donations awaiting pickup along a wall in an urban Native neighborhood. The orderly rectangles evoke modernist compositions in what Metchewais called “a Mondrian and serendipitous scene.” For the artist, they also stand in as one of many incarnations of home, both territorial and adopted. His shadow appears on the right edge of the photograph, an index of his presence in the Edmonton neighborhood that he called “an unofficial reservation in the city.”

Metchewais was ever conscious of the pitfalls of representation and stereotypes. In 1999 he began a post-doctoral fellowship at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and taught in the studio art program there until 2011, reaching the rank of associate professor. When he arrived in North Carolina, the birthplace of his white stepfather, he began to more regularly go by his mother’s maiden name, Metchewais, reflecting his difficult relationship with Mr. McLain. His course-planning notes include outlines of the histories of depicting Native America, from the trope of the noble savage to the erroneous notion of the vanishing race. His sketchbooks contain drawings based on art-historical representations, such as copies of the famous portraits of Native American delegates and visitors to Washington, DC, drawn by Charles Balthazar Julien Févret de Saint-Mémin, from 1804–7.

Yet Metchewais’s fully realized works show little of the typically overwhelming concern among Native American photographers of his generation with debunking and overturning such stereotypes. Instead, his self-portraits pursue the kind of “self-made Native imagery” he saw in online culture, as he wrote on Facebook in 2009. He fashioned a host of such characters as the Marlboro Indian smoking a cigarette in a cowboy hat (Marlboro Indian, 2000). In a series of self-portraits from 2000, Metchewais’s shirtless upper body, painted dark blue from the chin down, sparkles with starry points of light like the cosmological images from the late nineteenth-century ledger art of the Itázipčho Lakota artist and visionary Čhetáŋ Sápa’ (Black Hawk). Several photographs from Metchewais’s graduate-school period, Ghostdancer (1998) and Striped Man 02 (1998), depict his brother, Luther, wrapped head to toe in a black-and-white striped textile—a body that, while abstracted, evokes the heavily romanticized image of the Plains Indian wrapped in a chief’s blanket and the loaded history of disease-laden trade blankets.

In 1993, Metchewais was diagnosed with a brain tumor that chased him for the rest of his life. Surgery and subsequent treatments left him with a permanent bald spot on the back of his head. In a series of Polaroid self-portraits, Metchewais, in a white tank top and faded jeans, dons a hairpiece that stretches to the floor. In two Polaroids that he took to fully capture the length, he drapes the hair over one arm and allows it to drag along the floor beside his bare feet. In another Polaroid, the hairpiece is pictured lying snakelike on the floor. Long hair was a sign of Indianness to Metchewais, and he incorporated his own hair into some of his sculptural installations. In a 1984 comic for Windspeaker, a cartoonish Native man with long braided hair, perhaps representing the artist, asks, “Tell me . . . what is the true essence of being an Indian?!” A guru on a mountaintop replies, “That all depends . . . on if your mother married off the reserve before or after 1950 . . . how long yer hair is . . . how much pure blood you have.” Visual markers and the “poetics of identity”—hair, tobacco, place—were of great interest to Metchewais, who noted in the proposal for his University of North Carolina postdoc that it would be worthwhile to “question what it is to be an Indian with a white father.” The exaggerated length of the hairpiece and its visible artificiality compose an ironic take on this sign of Native identity while highlighting what was both a vulnerable feature for the artist and a site, as he explained, to investigate his “bi-racial identity and the ensuing ambiguity [that] falls in line with my interest in contradiction.”

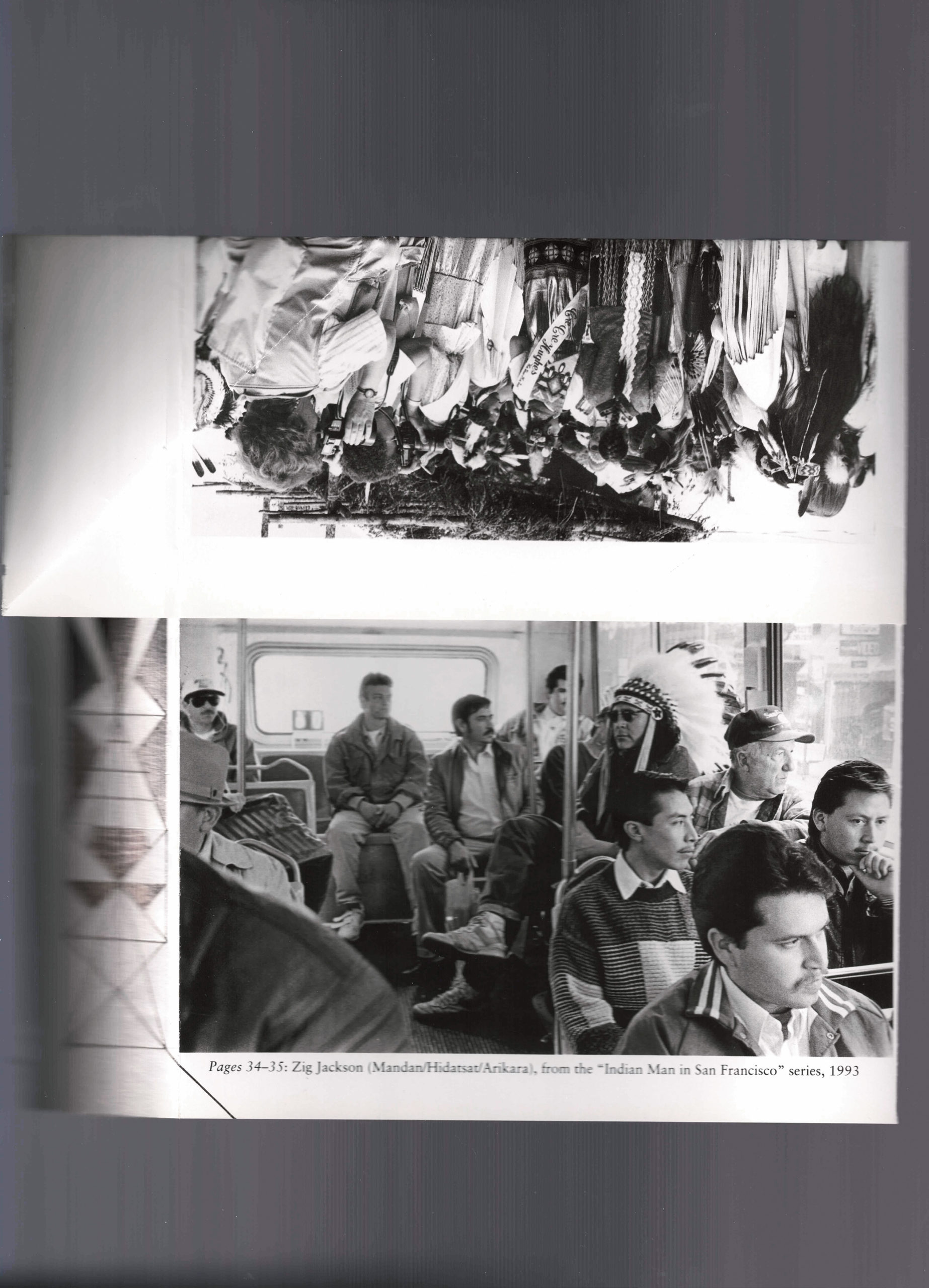

Kimowan Metchewais, Indian Handsign, Albuquerque, New Mexico, 1997

Following complications from one such surgery, in 2007, Metchewais lost the capacity for movement and feeling in the left side of his body. One notices that his hand-sign Polaroids are almost exclusively of his right hand. Many of the words labeling the Polaroids—“TOUCH,” “FLIGHT,” “RECALL,” “CHANGE”—took on a different valence in the wake of his partial paralysis. Metchewais called his studio “a laboratory” where he conducted an “archeology of the self,” and in the years following his surgery, he seemed to come to terms with his body, identity, and artistic practice. As curator Lois Taylor Biggs adeptly observes, “Metchewais blurred the boundaries of the body and the archive for the purpose of healing,” and his practice as personal archive served as medicine, both a “site of healing” and “a living body.”

Grow All Over Again (2008), a short film by Christina Wegs, intimately documents Metchewais discussing this process and his return to the studio after a hospital stay and period of rehabilitation. In the film, he describes a desire to revisit his old works and “to paint white and black rectangles over all the shit that I don’t like, and then go from there.” In a mixed-media work, Self-Portrait with Peach Brain Tumor (ca. 2006) the upper right and lower left sides of his face are split between two cut Polaroids that cast his skin color in different tones, one pink and the other bronze. Amid the Scotch tape is a series of inked black and beige rectangles that spread across the artist’s face but don’t mask his features. The original Polaroids were taken in 2000, prior to his 2007 surgery, but the modifications suggest he continued to explore his body as a site of the etched cultural markers of ethnic and corporeal identity.

As Metchewais rehabilitated and worked his way back into the physical studio, he began to transition his attention from analog photographic processes to the digital space, which he understood as a natural site for Indigenous subjectivity. “It turns out the thing in the modern world that most matches the Indian psyche is the web,” he wrote in 2009. His personal website and blog, “Images & Other Curios,” became a space to share his work, personal reflections on art and the artistic process, updates on his health, and other musings. He often gave his website background the texture of his folded paper works, bringing his love of photography’s tactility to the screen. He began a vibrant experimental video practice on YouTube, including kaleidoscopic treatments of his own face and banal videos of him shaving, and used Facebook and his blog as galleries for found images, not unlike his self-made Polaroid archive. The Facebook image portfolio labeled “Cree beadwork and modern color tactics” provocatively juxtaposes intricate abstract beadwork designs with artworks by the likes of Piet Mondrian, Josef Albers, and Fernand Léger. The internet, Metchewais astutely observed, could be a site where one could collide modernist and Indigenous histories to sovereign visual ends. “Indians exist in impossible spaces,” he noted, “and [the web] has given us a purchase on the power of our space.”

In the composition Hymn over Water (2000), syllabics hover over the horizon line of Cold Lake, and above them is the phrase “Air: Vole au plus tôt” (Fly as soon as possible). The French phrase and syllabics are sourced from a Dene hymnal; the receding water, slightly out of focus, is sourced from one of the many trips Metchewais took back home. In this portrait of Cold Lake, there are no figures bathing in its waters, only the hymn, which hangs like a caption, an ode to the land. Language and the translation of word to image are central themes of Metchewais’s work, and here the French and Dene texts transition into the rhythmic pattern of the waves, an attempt by Metchewais, perhaps, to translate words into the omniscient language of the land.

In early 2009, Metchewais posted an image of Self-portrait with Peach Brain Tumor to his online blog alongside a text addressing the return of symptoms from his brain tumor. “Now that it’s been confirmed with a brain scan that my brain tumor has changed its shape, I can stop playing games of self-denial. . . . Things move quickly now. My brain surgeon already called this morning to set up a consult this coming Tuesday morning. My main questions are these: Can I decide not to have surgery? And, if I opt out of surgery, what then happens? I noticed that I saw a prism rainbow on the wall and felt a little delight, which leads me to believe that my good spirit is still intact, not to mention my artistic vision.”

In July 2011, Metchewais passed away at his mother’s home in Alberta. The artist gifted his personal collection and archive to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian, which finalized the accession in 2015. In addition to this legacy, traces of his presence remain online. The photographer and scholar Hulleah Tsinhnahjinnie said shortly after the artist’s passing that “Kimowan’s creative spirit did not hesitate about living with death, and it was with a genuine thoughtfulness he has bequeathed his digital presence so that we may consider our own existence.” Metchewais’s final works move between digital, photographic, and earthly spaces, like the hymnal syllabics hovering between celestial and watery realms. In a July 2008 YouTube video diary, “tellytwoface returns from the rez,” Metchewais recounts a recent trip to Cold Lake following his recovery from surgery. He describes in near baptismal terms a full-bodied plunge into its cool waters, dipping his body as a kind of prayer. “To go in the water and come back out, and see that view. That’s good medicine. . . . I’m back and I feel full. I’m really full.”

This essay originally originally appeared in Kimowan Metchewais: A Kind of Prayer (Aperture, 2023).