Terry Evans, Pond and Sky, Western Saline County, Kansas, May 8, 1991.

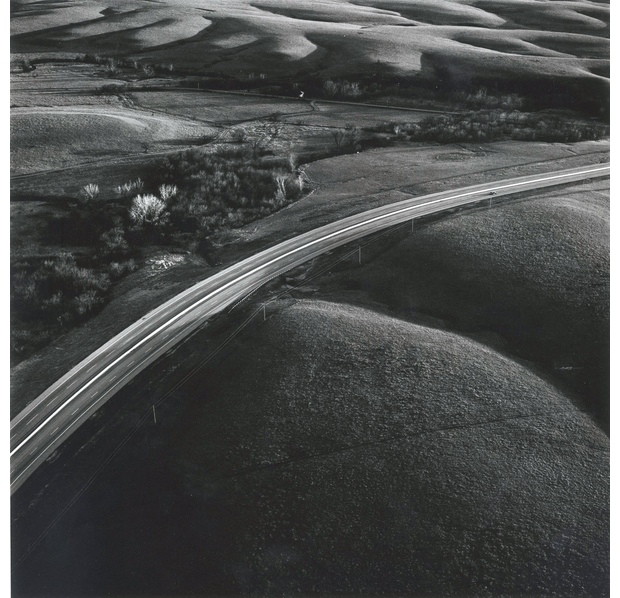

Terry Evans’s The Inhabited Prairie grasps a thread of photographic history that has preoccupied many, from Alfred Stieglitz to Sally Mann: the material, chemical, and divine properties of light. Evans hired two pilots, Duane Gulker and Major Jonathan Baxt, to explore the American prairie from above; together they boarded a Cessna 172 airplane and flew low above the plains, affording a particular perspective that lies at the upper register of human scale. At this height, one catches the faintest glimpse of the entirety of the earth, yet allusions to the prairie’s human inhabitants are markedly apparent: houses, cattle tracks, tires, hay bales, trees, graves. The resulting photographs depict a relationship between living organisms and the terrain they inhabit. The earth itself is given character, as a divine body. Flight, as a methodology for making photographs, could also be characterized as an act of piety, as a prayer or even ascension. Nonetheless, Evans’s use of celestial perspective encourages an awareness of three irrefutable forces of nature: gravity, entropy, and light.

Through Evans’s eyes, the earth appears planar, albeit with a slight curve. A simple optical truth: a single luminary, the sun, illuminates a single plane, the earth. A simple physical truth: gravity presides over matter. Our earthbound lives sometimes mask these axioms, yet flight provides Evans with a unique relationship to light that animates the elements that compose the earth. As she floats through the air, she authors images that, by her very positioning, call attention to our subjection to those natural laws.

Nineteen prints hang on the wall at Yancey Richardson Gallery, all of them vintage excepting one, the largest image, Intersecting the Flint Hills, April (1994). The majority are hung in square frames approximately twenty-four inches a side. These pre-digital prints, sized smaller than tableaux, ensure the landscapes retain a personal and meditative affect.

Cattle Feed Lot, West of Saline County, Kansas, April 24 (1990) is an exquisite composition in which a herd is shot from almost directly overhead. The orthogonal perspective gives the cattle the precarious semblance of sliding off the plane of the earth, and particular attention is paid to the patterns the steers’ tracks leave as they mill about their pen. Indeed, Evans maps the order and tools of industrial agro-business alongside abandoned military infrastructure and the humblest domestic decorations. A prisoner-of-war camp, abandoned at the end of the Second World War, sits alongside livestock feedlots and prairie homesteads, many of which are abandoned as well. These variances in land use, from their rise to their ruin, catalog the futile combat between civilization and entropy as it unfolds over time. Evans illustrates the idea that the great American Prairie will endure longer than the men and women who inhabit it, and that the order brought by agriculture, development, and war, when viewed from the air, displays many of the same fractal, diffused, organic qualities that characterize many systems of nature. And that the semantic cuts humans make upon the earth, the parceling of the land and its exploitation, cannot and will not interrupt the mottled texture of the plain.

All the while, this drama is soaked in warm Midwestern sunlight, which, despite the single hue of silver gelatin, shines through in Evans’s prints. On the prairie, light and shadow are ubiquitous and pay no respect to manmade boundaries; after all, light is fundamental to the experiment of agriculture, and therefore to our subsistence. Light bounds and bends and envelops the globe; it fills the most oblique nook and cranny and implicates itself even in its absence. It is impossible to imagine life without light; and while this may be self-evident—light is taken for granted anytime one reads past sunset, drives at night, or goes underground—with The Inhabited Prairie, Evans pays homage to that most sacred illumination.

Terry Evans’s exhibition The Inhabited Prairie is on view through July 3 at Yancey Richardson Gallery in New York.