Lartigue: Life in Color

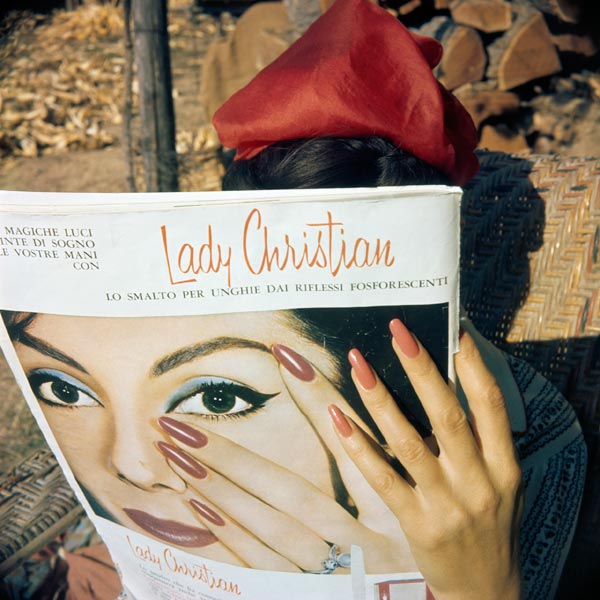

J. H. Lartigue, Florette, Vence, May 1954 © Ministère de la Culture–France/AAJHL

From the age of seven, Jacques Henri Lartigue photographed his wealthy friends and family flying homemade gliders, somersaulting, and racing bobsleds. Apart from occasional publication in the sports magazine La vie au grand air, these images did not make it beyond the family albums until 1963, when Museum of Modern Art curator John Szarkowski exhibited them as curious objects from the annals of modernity. Fame followed the same year with the publication of Lartigue’s work in Life magazine, and later in Boyhood Photos of J. H. Lartigue: The Family Album of a Gilded Age (1966), and Diary of a Century (1970), a collection of Lartigue’s photographs and diary entries edited by Richard Avedon. The belated discovery of Lartigue mirrors the trajectory of the snapshot into the fine arts canon, where it is by now comfortably nested.

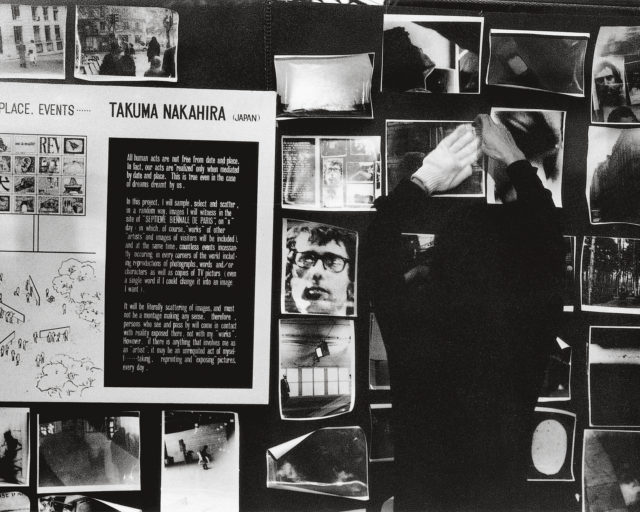

J. H. Lartigue, Sylvana Empain, Juan-les-Pins, August 1961 © Ministère de la Culture–France/AAJHL

Not so for Lartigue’s color photographs, which represent an astounding 40 percent of the 117,577 images in the estate held by the Donation Jacques Henri Lartigue. It would be another seventeen years before the publication of The Autochromes of J. H. Lartigue, 1912–1927 (1980), by Georges Herscher, solely devoted to Lartigue’s experiments with this pioneering, early twentieth-century color process. Another thirty-five years later, both his autochromes and Ektachromes have made it to the walls of the Maison Européenne de la Photographie, in Paris, and Foam, in Amsterdam, respectively. Lartigue: Life in Colour, an exhibition currently on view at Foam, features some 140 color reproductions ranging in date from 1912 to 1983. The selection is largely sourced from Lartigue’s personal albums, and exhibited in roughly chronological chapters: autochromes, seasons, portraits, and travel.

J. H. Lartigue, Bibi in the Île Saint-Honorat, Cannes, 1927 © Ministère de la Culture France/AAJHL

Lartigue’s autochromes comprise a colorful reunion with all our favorite characters. We recognize Lartigue’s older brother Zissou with his glider (1914), and his beloved cousin Simone in her (blue!) bobsled wearing a stylish green ensemble (1913). But the plane is no longer airborne. And Simone is keeping still not to ruin the picture, instead of crashing down a gravel road with her tongue out, like she would in sepia. Due to the long exposure time dictated by the autochrome, Lartigue’s relatives are stalled in their playful banter to accommodate the sluggishness of the early color process.

J. H. Lartigue, Florette, Megève, March 1965 © Ministère de la Culture–France/AAJHL

“Is this still Lartigue? Are we disfiguring an artist?” curator Martine Ravache asks in the accompanying exhibition catalogue Lartigue: Life in Color, recently published by Abrams. Apart from the occasional leaping dog or bobsled, the subject matter is often quaint, even sentimental. The color prints display exactly the pictorial quality for which Lartigue’s black-and-white work had been deemed antithetical. This realization, which is as fascinating as it is uncomfortable, is downplayed by presenting Lartigue as a painter at heart who proclaimed to “see everything with my painter’s eye.”

J. H. Lartigue, Brittany, 1965 © Ministère de la Culture–France/AAJHL

Yet the picturesque subject matter is not enough to undermine his status as the lovechild of modernity—on the contrary. From the pink pastel of Bibi’s dainty hands (1921) to the fiery red nails of Florette and her glossy magazine (1961), the prints testify to Lartigue’s eagerness to experiment with any new photographic process he could get his hands on. The color work constitutes more than the diaristic musings of a man in love. Marcelle “Coco” Paolucci is conspicuous by her absence, a hiatus that speaks more to the stalled development of color photography than disaffection for his second wife. Discouraged by the sluggishness of the autochrome process, Lartigue stopped photographing in color in 1927. He did not start again until 1949, after two world wars and the development of Ektachrome film.

J. H. Lartigue, Florette’s hands, Brie-le-Néflier, 1961 © Ministère de la Culture–France/AAJHL

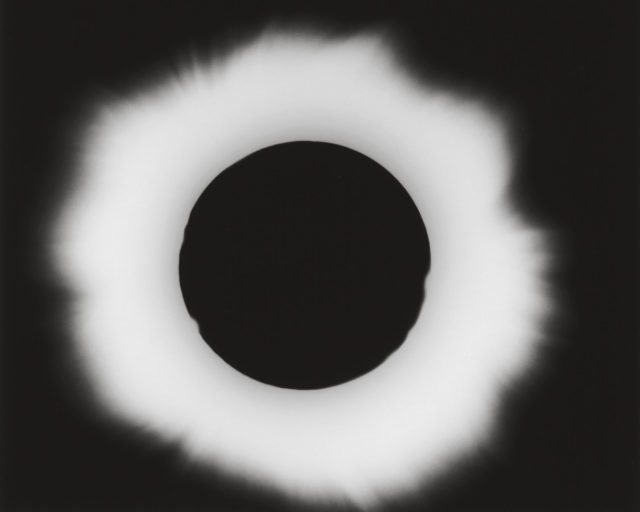

In Lartigue’s unrelenting quest to stall time with whatever medium, color photography would prove his worst ally. The unique glass plates of the autochromes are too fragile to exhibit; his Ektachromes demanded intense restoration before reproduction. Albeit prescribed by preservation, the grainy enlargements fail to communicate the refined brilliance of an actual autochrome, or the three-dimensional experience of a stereoscopic image. Even the albums, diaries, and logs kept by Lartigue have not made it into the showcase. They are represented by facsimiles on museum board that do little but emphasize the absence of the originals.

J. H. Lartigue, Jacqueline Roque and Picasso, Jean Cocteau, Francine and Carole Weisweiller, and sitting in front, Florette, bullfight, Vallauris, 1955 © Ministère de la Culture–France/AAJHL

In the spirit of Lartigue, the battle against oblivion is waged with the reproductive means of our time. Other exhibitions at Foam, such as Vivian Maier: Street Photographer (2015) and Francesca Woodman: On Being an Angel (on view concurrently with Lartigue) display a curatorial concern for rediscovery and reproduction of the archive. Tracing the incremental disclosure of Lartigue’s albums since Szarkowski reveals the making of an artist through careful curation. And so the exhibition texts about Lartigue’s love for the seasons or his relationship with God sidestep the more uneasy subtext: the jerky trajectory of Lartigue’s color photographs from the amateur album to the museum wall.

Lartigue: Life in Colour is on view at Foam, Amsterdam, through April 3, 2016.