LaToya Ruby Frazier's Curriculum

Growing up in Braddock, Pennsylvania, photographer LaToya Ruby Frazier saw firsthand the economic and environmental decline and racism that affected her industrial hometown, subjects she explores through a personal documentary approach. For twelve years, she photographed her mother, grandmother, and herself in the series of deeply evocative images contained in her book The Notion of Family, published by Aperture in 2014. Also a lecturer and professor, Frazier is among the most compelling new voices working within and expanding the tradition of documentary photography today. For Aperture‘s Summer 2015 issue, the editors asked Frazier to contribute to the magazine’s regular Curriculum column, where photographers discuss readings and works of art that have informed their thinking. On May 14, Aperture’s gallery in New York City will open an exhibition of Frazier’s, culled from The Notion of Family, which just received an Infinity Award from the International Center of Photography. This article appeared in Aperture magazine issue #219 and issue 7 of the Aperture Photography App. Click here to buy the issue and read the entire article and click here to download Aperture’s free app for more great content.

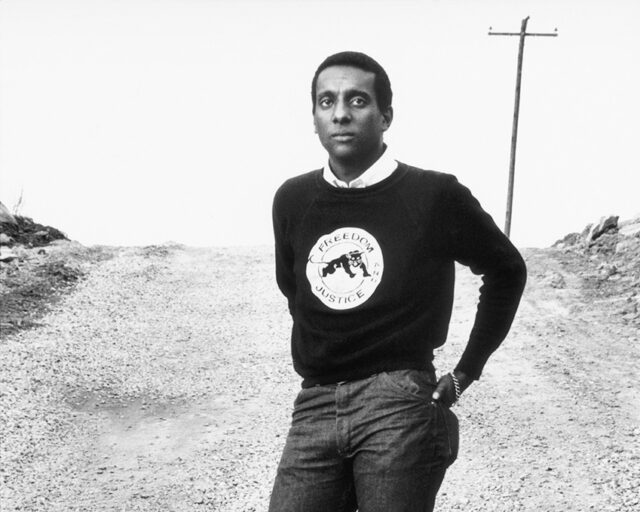

Eve Arnold, Gordon Parks, 1964 © Eve Arnold/Magnum Photos

Gordon Parks, A Choice of Weapons, 1966

Gordon Parks’s memoir taught me the best reason to pick up a camera: “My deepest instincts told me that I would not perish. Poverty and bigotry would still be around, but at last I could fight them on even terms.” It is a story of strength, courage, honor—a will to survive and make a mark on history. His ability to express his disdain for poverty, racism, and discrimination in America through eloquent, beautiful, and dignified photographs is timeless. Any student struggling to understand why some photographers document humanity will gain insight from this autobiography.

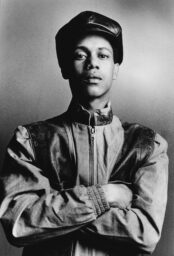

Fred W. McDarrah, Jamaica Kincaid, New York, 1974 © The Estate of Fred W. McDarrah/Getty Images

Jamaica Kincaid, A Small Place, 1988

I’ve been fascinated by literature’s freedom to render the complexities of dark childhood memories and abject realities. Kincaid’s fictions, semiautobiographies, and multiple points of view are intensely rich and unapologetically evocative. Her ability to take on themes of patriarchal oppression, colonialism, race, gender, loss, adolescence, and ambivalence between mothers and daughters inspires me. Any reader who wants descriptions of familial relationships or a sense of human relationships to homeland, economy, and education could certainly glean universal themes from Kincaid.

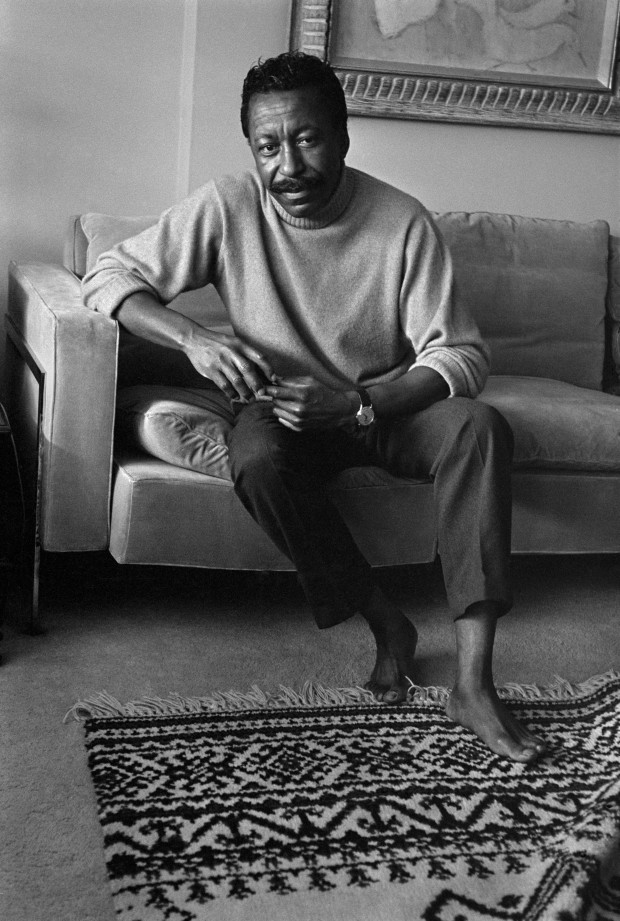

Charles Burnett, film still from Killer of Sheep, 1977 © Charles Burnett and courtesy Milestone Film & Video

Charles Burnett, Killer of Sheep, 1977

My understanding of how to create atmosphere, mood, and narrative largely comes from my love of film and cinema—from Michelangelo Antonioni, Ingmar Bergman, Alfred Hitchcock, and Charles Burnett to Wong Kar-wai. I love showing my students the relationship between these filmmakers’ visual language and that of classic photographers, like Eugène Atget, August Sander, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Walker Evans, and Parks. With its soundtrack and lyrical visual language, Killer of Sheep is the ultimate masterpiece. Set in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles, a portrait of American life is rendered as the protagonist Stan struggles with social class and disillusionment while working long hours at a slaughterhouse; the stress to generate financial stability strains relationships with his wife and close friends. The film is an incredible depiction of how we negotiate intimacy and how we are restricted by landscapes and labor.

Jason Moran, “Artists Ought to Be Writing,” from the album Artist in Residence, 2006

Sometimes when I’m editing in the studio, I play music by jazz pianist and composer Jason Moran. I was brought deeper into his music when I heard artist Adrian Piper’s voice in his song “Artists Ought to Be Writing.” While writing the text to accompany my photographs in my first book, I followed Piper’s instructions: “Artists ought to be writing about what they do and what kinds of procedures they go through to realize a work. . . . If artists’ intentions and ideas were more accessible to the general public, I think it might break down some of the barriers of misunderstanding between the art world and artists and the general public.”

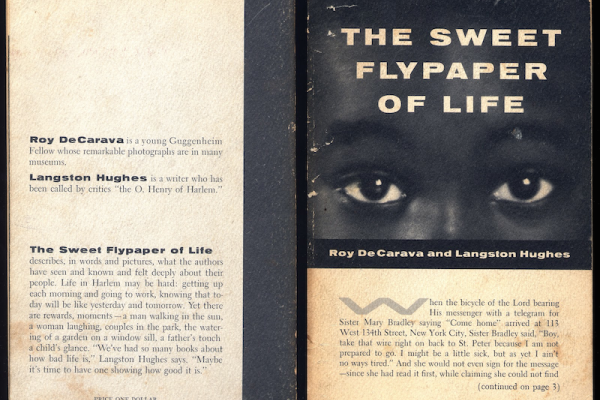

Roy DeCarava and Langston Hughes, The Sweet Flypaper of Life, 1955

DeCarava and Hughes’s collaboration is a perfect example of how history can be reclaimed and redirected through storytelling and imagination. Hughes’s words take us through the eyes of a fictitious grandmother to reveal a representation and memory of Harlem that is at odds with the unloved depictions reported by mainstream media in the 1950s. Hughes’s last book, Black Misery (1969), is seldom discussed or quoted, but this line resonates with my work: “Misery is when you heard on the radio that the neighborhood you live in is a slum but you always thought it was home.”

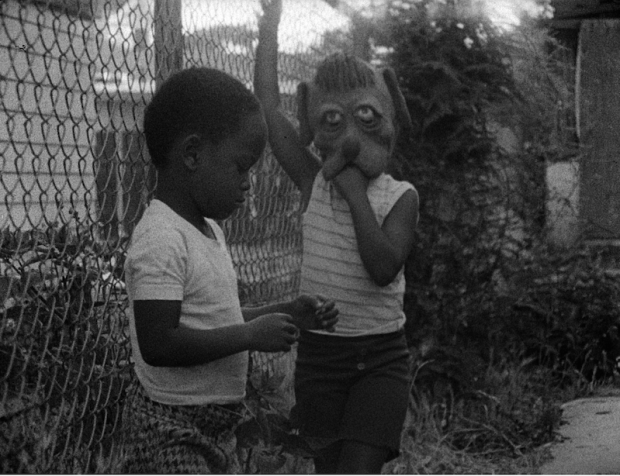

Emory Douglas, Untitled, from Black Panther, February 17, 1970 © Emory Douglas and Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York

New Museum survey, Emory Douglas: Black Panther, 2009

Though I speak primarily through photography, I am not limited to it. Occasionally, I work in video and performance. When I look at the artwork, illustrations, prints, and roles of Emory Douglas as a revolutionary artist and minister of culture for his community, I am reminded of Bertolt Brecht’s The Popular and the Realistic (1938): “There is only one ally against growing barbarism—the people, who suffer so greatly from it. It is only from them that one can expect anything. . . . .Anyone who is not a victim of formalistic prejudices knows that the truth can be suppressed in many ways and must be expressed in many ways.”

August Wilson, The Piano Lesson, 1990

I watch this play to understand the great migration from the South, self-worth, and how to put my cultural legacy to use creatively.

Albert and David Maysles, film still from Grey Gardens, 1975 © Maysles Films Inc., via Portrait Releasing Inc.

Albert and David Maysles, Grey Gardens, 1975

This is the film that helped guide me into my collaborations with my mother. Full of compassion and without judgment, this brilliant documentary takes cinema verité and psychological space to another dimension. Shot over a six-week period of time, the Maysles brothers’ encounters with Edie and Edith Beale are not shown in chronological order. This destabilizes the viewer’s sense of time and heightens the complexity of the Beales’ relationship. The passage of time is indicated through a gradual collapse of a dilapidated wall; at the beginning it’s a hole in the plaster, toward the middle the hole expands, and by the end it falls completely as a raccoon crawls out. This is a great example of how time can be used as metaphor and to build tension in a set of relationships.