Rich, Famous, and Faking it

Rich, Famous, and Faking it

For twenty-five years, Lauren Greenfield has chronicled the rise and fallout of consumerism and celebrity culture.

Lauren Greenfield, Film director and producer Brett Ratner, 29, and Russell Simmons, 41, a businessman and cofounder of hip-hop label Def Jam, at L’Iguane restaurant, St. Barts. Few establishments on the island accepted credit cards, and visitors often carried large amounts of cash, 1998

© the artist and courtesy the Annenberg Space for Photography

Few photographers have cast as unflinching an eye on the outrageously wealthy as Lauren Greenfield. Her 2012 film The Queen of Versailles follows billionaire “Time Share King” David Siegel and his wife, Jackie, as they attempt to build the largest home in America, only to be sidelined by the 2008 financial crisis. But Greenfield’s fascination with the trappings of consumerism began in the early ’90s. On the heels of a National Geographic assignment in Chiapas, Mexico, Greenfield made the choice to focus closer to home: on a group of teenagers in her hometown, Los Angeles. The resulting body of work, Fast Forward: Growing Up in the Shadow of Hollywood (1997), offered a look into youth culture that was at once hopeful, tragic, and wholly American. Present throughout Greenfield’s work over the last twenty-five years is a dedication to bringing forth deeply personal narratives—a testament to the intimate and long-standing relationships she forges with her subjects. I spoke with Greenfield as she prepared for her retrospective, Generation Wealth, currently on view at the Annenberg Space for Photography in Los Angeles.

Lauren Greenfield, Jackie and friends with Versace handbags at a private opening at the Versace store, Beverly Hills, California, 2007

© the artist and courtesy the Annenberg Space for Photography

Katie Booth: Did you feel like an outsider in the worlds you’ve entered? How has your own background shaped your photography?

Lauren Greenfield: In a way it was really the opposite. My parents didn’t buy into the materialistic values of LA, but as a teenager wanting to fit in, I still wanted designer jeans, and to have a car at sixteen like my friends did. My work comes from that contradiction: even growing up with parents who did not participate in conspicuous consumption, I was interested in symbols of wealth and glamour. As a photographer, even in the most extreme places, I feel a mix of empathy and ability to relate. The work is about the aspiration for wealth and luxury, and the striving to be “other” than you are. Whether it’s the patients in the anorexia clinic from Thin (2006), or Jackie Siegel from The Queen of Versailles, I had to like the people to spend so much time with them. When I’m with my subjects, I focus on what makes them tick, and their behavior, rather than my status as an outsider. I’m more interested in the common ground, and how we’re all complicit in this story.

Booth: Your photographs expose the dark side of wealth, but typically these people control their own images. What do you think motivated your subjects to let their guard down, such as the Seigel family in The Queen of Versailles? Is it because they trust you as a photographer, or something more?

Greenfield: A lot of the work in Generation Wealth is longitudinal, so I think part of it is developing trust and relationships. Many people who I document desire fame and recognition. More profoundly, people want to share their stories, which I’ve tried to do in a long-term, respectful way. I think with The Queen of Versailles and with Thin, my subjects could sense that I’m not seeking to criticize them. I’m interested in the humanity of their stories, how their stories reflect all of us. In the case of The Queen of Versailles for example, the story of David and Jackie wanting more—a 90,000-square-foot home inspired by the château of Versailles, rather than the 26,000-square-foot mansion they lived in—and being willing to overextend to get it, was an allegory that spoke to, in supersized terms, how many Americans from a variety of backgrounds (and even others I documented internationally in Ireland, Iceland, and Dubai) get wrapped up in the same cycle of addictive consumerism.

Lauren Greenfield, Xue Qiwen, 43, in her Shanghai apartment, decorated with furniture from her favorite brand, Versace, 2005

© the artist and courtesy the Annenberg Space for Photography

Booth: Your work connects threads that might, in another context, seem disparate: alongside images of millionaires and celebrities in Beverly Hills are pictures of migrant workers, squatters, and strippers. Is there a unifying quality or feeling present in your subjects that transcends their socioeconomic status?

Greenfield: Definitely. I’m looking at how the values of our culture have shifted in a way that affects people beyond socioeconomic status, race, or nationality. In the United States, we have a culture that has been deeply influenced by materialism, the cult of celebrity, the importance of image. Globalism and mass media have disseminated these values across the world. I look at how girls are affected, how kids are affected, how people in communist countries are affected, and how we all made the same mistakes that led to the 2008 crash.

Booth: In this project, and much of your work, you focus on women and girls. Juliet Schor, in her introduction to Generation Wealth, notes that “sex greases the wheels of commerce” and that the performance of wealth is typically by men, while “women serve as props and audience for their acts.” Do you agree with these statements?

Greenfield: I think that’s part of the story. I’m interested in how girls are marketed to, but also how they are sold. When girls learn from a young age that their value comes from their body, their reaction is to leverage that value, whether it’s by posting a sexy picture on Instagram, or actually selling their body. In the “Sexual Capital” chapter, there’s a story of Brooke Taylor, a college-educated, Midwestern woman who was working as a social worker making four hundred dollars a week, and who decided to become a prostitute. She makes ten thousand dollars a day, and is happy with her choice. In a world where money is the metric of success, and people don’t feel as bound by traditional conventions of morality, that choice becomes rational. I’m interested in the culture that creates that.

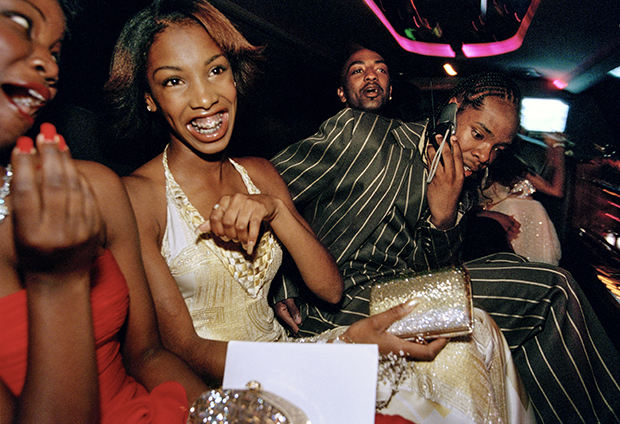

Lauren Greenfield, Crenshaw High School girls selected by a magazine to receive “Oscar treatment” for a prom photo shoot take a limo to the event with their dates, Culver City, California, 2001

© the artist and courtesy the Annenberg Space for Photography

Booth: Do you think consumerism places a disproportionate burden on women?

Greenfield: Well, I think capitalism thrives on insecurity, and where you have insecurity, you have a great consumer. If you tell somebody they’re not good enough, but if they buy this product, they will be, that’s a perfect way to sell. Women and girls are particularly vulnerable, because of their insecurity about body image, and self-esteem, but I don’t think they’re the only ones. Boys are becoming increasingly vulnerable because they are being objectified, too. Older people as well. We live in a culture that values youth.

Booth: Your ad for Always, “Like a Girl,” was the first feminine product ad to run during the Superbowl, and was proven to have a positive impact on the way girls perceived themselves. What do you think will be the most powerful effect of bringing all of this work together in the context of a book and exhibition?

Greenfield: I think we’re at a critical moment in history, and our path is not sustainable. Popular culture is ubiquitous and all-consuming. Questioning and discussing this culture makes us less vulnerable to its influence, decreases its power, and increases our agency. “Girl” is often used as an insult and nobody thought about it. That campaign showed how disempowering that is.

Lauren Greenfield, Ilona at home with her daughter, Michelle, 4, Moscow, 2012

© the artist and courtesy the Annenberg Space for Photography exhibition

Booth: In On Photography, Susan Sontag writes, “Needing to have reality confirmed and experience enhanced by photographs is an aesthetic consumerism to which everyone is now addicted.” With the rise of social media, how have you seen photography, and images of ourselves, fit into consumer culture?

Greenfield: That’s a prophetic statement. Photography has been completely democratized, and has become part of everyone’s personal branding. The way kids brand themselves is kind of a natural extension of this work. When you ask kids what they want to be when they grow up now, the most common response is “rich and famous.”

Booth: You’ve drawn parallels between David Siegel and President Trump. Many liberals and pundits expressed shock at the impossibility of his win, but, looking through Generation Wealth, are you at all surprised at his massive political following?

Greenfield: I had the same reaction. I was completely shocked. But Trump’s election also validates my work. It looks like a straight line, from the early work in LA, to the rise of celebrity worship and the idea of “fake it ’til you make it,” with the backdrop of inequality and the feeling of the loss of the real American dream and real social mobility. On a personal level, I was surprised, because I was probably in the West Coast bubble like so many others, but I also feel like that makes the work important to think about now. I hope that people have the same reaction, and that this project can shed light on where we’re at now, in a culture that brought about Donald Trump.

Generation Wealth is on view at the Annenberg Space for Photography, Los Angeles, through August 13, 2017.