Lecture as Performance

Lebanese artists Walid Raad, Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, and Rabih Mroué and Lina Saneh have all embraced the artist’s talk to unpack history and the limitations of the photograph.

© Walid Raad and courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

In the last twenty years, the Lebanese artist Walid Raad has produced two major, long-term, multifaceted bodies of work. The first, known as the Atlas Group, delves into the mechanisms of history and memory that have been used to convey the experience of Lebanon’s civil war, a conflict that lasted roughly fifteen years, from 1975 through 1990. The second, titled Scratching on Things I Could Disavow, considers how the construction of institutions and infrastructures for contemporary art is changing the cultural landscape of the modern Middle East. Although one followed the other and they remain fairly distinct, the Atlas Group and Scratching are linked by several lines of inquiry and the strands of Raad’s practice. Taken together, his projects involve an ever-expanding constellation of prints, photographs, Polaroids, drawings, cutouts, collages, sculptures, videos, Super 8 films, a white Fiat, plaster casts of a bomb crater, miniature exhibition models, monochromes, trompe l’oeil murals, a maze of fake doorways, and a dazzling cast of imagined characters, including a gambling historian, a melancholy intelligence agent, a sorrowful police inspector, a long-suffering photographer, a forgotten curator, and a pioneering performance artist who made gorgeous ink-on-paper abstractions in her youth.

The two projects meet at several important points of intersection, primary among them the formal precision of the lecture-performance, which extends through both bodies of work and is unique to the context from which Raad’s practice first emerged. In the period after the civil war ended, the Lebanese capital Beirut proved itself a strange and powerful incubator for new thinking about art and photography, as a tight-knit group of colleagues took the setup and structure of an artist’s talk to start an open-ended conversation about the behavior of images in proximity to wars and other forms of political violence. That conversation persists to this day. Raad is now one of the leading practitioners of the lecture-performance internationally, but his works continue to unfold in close dialogue with those of his Beirut-based peers, most notably the joint efforts of Rabih Mroué and Lina Saneh, who are rooted in theater, and Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, who come from the world of film. The Atlas Group earned Raad a reputation as something of a trickster. When he first began showing his work in exhibitions, lecture programs, and film festivals in the late 1990s, he presented himself not as the author per se but rather as a spokesperson for a foundation that had been established to research the recent history of Lebanon. The Atlas Group, according to Raad, was based in Beirut, where its founding members were gathering a wealth of documentary materials, including the photographs, films, and notebooks filled with heavily annotated newspaper clippings that Raad was sharing on their behalf. Within a few years, the Atlas Group was revealed to be a clever fiction. The colorful donors who had given the foundation their effects were all, in fact, figments of the artist’s imagination. Their photographs were either found in the archives of Lebanon’s daily newspapers, borrowed from albums belonging to Raad’s father, or taken by Raad himself, when he was a teenager messing around with his first camera on the eve of the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982.

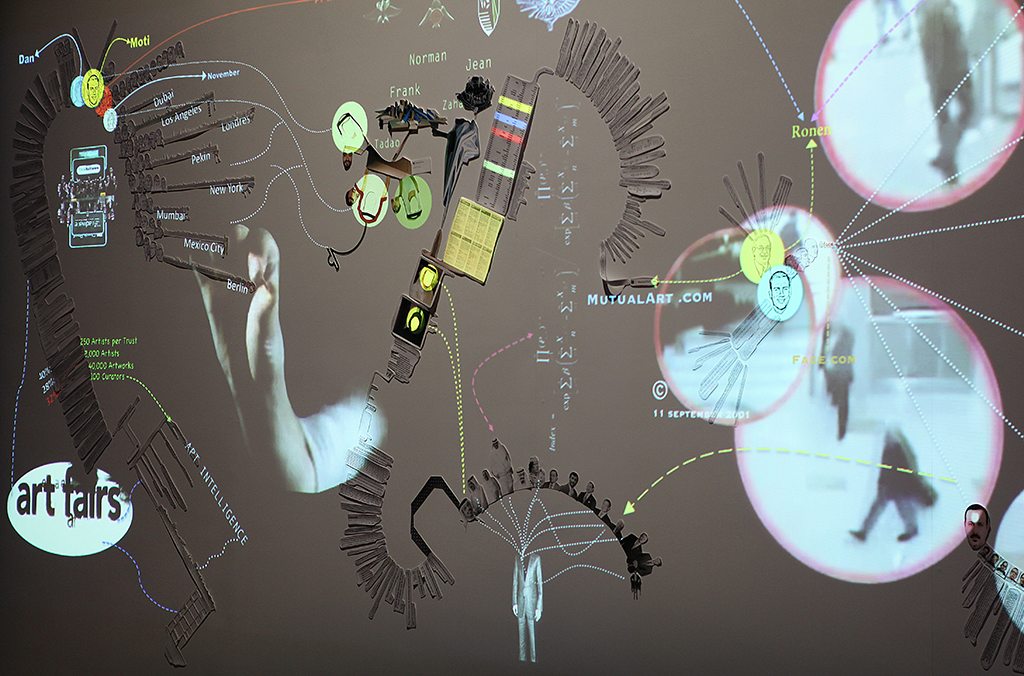

However true or false, the Atlas Group was emblematic of Lebanon’s postwar era, a time for sifting through the wreckage of the past to find the materials for building a better future, not least through the creation of new institutions. By the time the project came to an end, in the mid-2000s, the regional landscape had shifted and another kind of institution-building took hold of the artist’s imagination—the creation of massive new museum projects in the Persian Gulf. With no shortage of ambition, the new cities of Dubai, Abu Dhabi, and Doha hoped to surpass the old cities of Beirut, Cairo, and Baghdad as the Arab world’s preeminent centers of artistic production. Raad’s second project, organized in parts corresponding to the sections of a book (preface, plates, appendices), has so far created (or imaginatively recomposed) genealogies of Arab artists, bibliographies of Middle Eastern modernism, and the oddly anachronistic architectural details of future museums. Whole series in Scratching on Things I Could Disavow sketch out a fictional prehistory and forecast the opening scenarios for the branches of the Guggenheim and the Louvre that Abu Dhabi is building on a spit of reclaimed land known as Saadiyat Island.

To encounter Raad’s work has thus become an exercise in entertaining doubts, skepticisms, and suspicions. The artist initiates viewers in a game of second-guessing, but at the same time, on a subtler level, he also engages them in a serious critique of photography, image making, and the status of art. Lavish in their materials and details, extensive in their background stories and accompanying texts, his works tend to be as accumulative and dense as they are conceptually succinct. How interesting, then, that the centerpiece of Raad’s first major museum survey in the United States, currently on view at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, is neither a sequence of photographic prints purporting to show the engines that have been ejected from car bomb blasts (a hundred of them appear in the series My Neck Is Thinner than a Hair: Engines [1996–2001]), nor the videotaped eyewitness testimony of the only Arab hostage held with Americans such as Terry Anderson for a decade during the civil war (as conveyed in the sixteen-minute video Hostage: The Bachar Tapes [2001]), nor a collection of color-saturated still lifes capturing objects from the Louvre that will be inexplicably altered by their transfer from Paris to Abu Dhabi in 2026 (as imagined in the series Preface to the Third Edition [2013]), although all of these works are included in the show. Rather, the heart of the exhibition is an hour-long performance piece, which the artist is presenting more than seventy times in total—once a day, five days a week, for an audience of forty to fifty people each time.

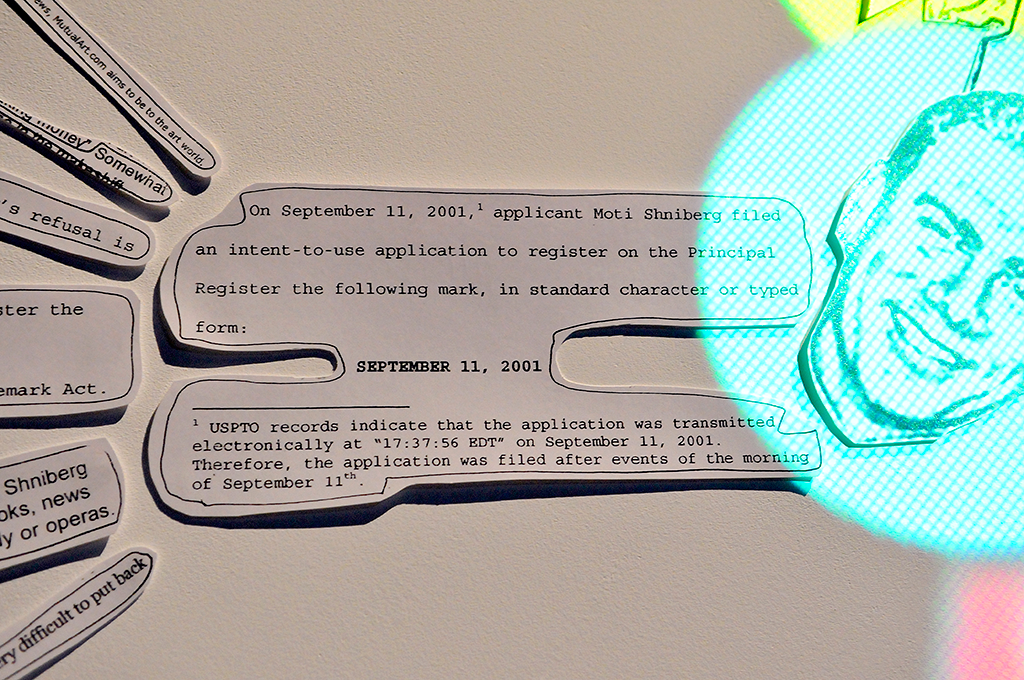

Almost all of the works associated with the Atlas Group and Scratching exist in multiple formats. The dates, details, sometimes even the titles of individual pieces exist in a constant state of flux, changing from one context to another. But from their earliest iterations, both projects have always come across as the most seamless and conceptually airtight in the live performances that test the durability of Raad’s materials, setting them down in a crosscurrent of politics, theory, and old-fashioned storytelling. The Loudest Muttering Is Over: Documents from the Atlas Group Archive (2003) established the setup, with the artist always seated at a table, a lamp, a bottle of water, a script, and a laptop before him, and a screen for the projection of images behind. I Feel a Great Desire to Meet the Masses Once Again (2005), about security panic and the war on terrorism in post-9/11 America and Raad’s first work authored under his own name, was in many ways the hinge between the Atlas Group and Scratching. The same style of lecture performance carries into the second project. Scratching on Things I Could Disavow: Walkthrough (2013), the core of the MoMA show, is the apotheosis of that project, and Raad’s most theatrical work to date. It begins with an exposé of the Artist Pension Trust, an investment fund for artists; tunnels into the Israeli high-tech industry, data mining, and the algorithms turning seemingly irreducible works of art into tradable financial assets; and then jumps headlong into the future, to the opening of the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, vaguely a decade from now, when an unnamed Arab artist will find himself mysteriously, inexplicably stricken, felled at the doorway, unable to enter.