Letters from Sally Mann On Process

The following letters from Sally Mann to Melissa Harris, now editor-in-chief of Aperture Foundation, originally appeared as a part of an interview on Mann’s process in Aperture #138, “On Location,” in 1995. This month, Aperture reissues the paperback version of Mann’s Immediate Family, originally published in 1992, on the occasion of this year’s release of her autobiography, Hold Still. This fall, Aperture Foundation launches the Aperture Digital Archive, giving subscribers access to every issue of Aperture magazine to subscribers.

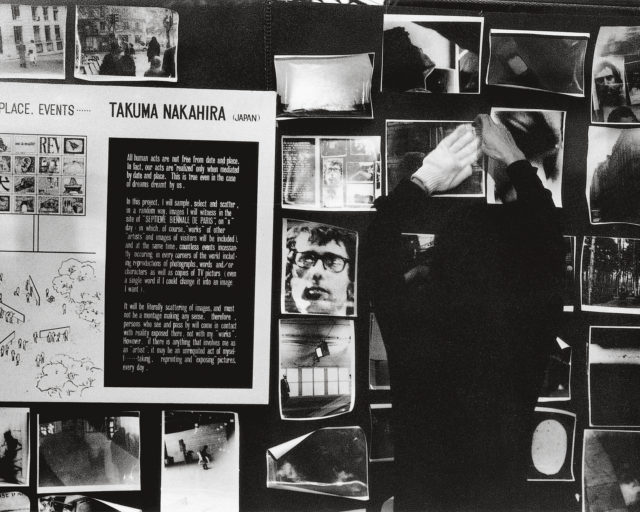

Sally Mann, Torn Jeans, 1990 © Sally Mann

July 1, 1994, Lexington, Virginia

Dear Melissa,

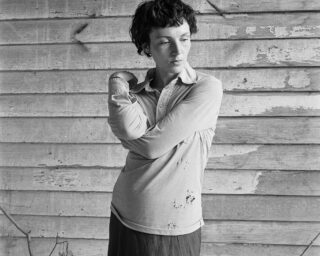

I sense that there’s something strange happening in the family pictures. The kids seem to be disappearing from the image, receding into the landscape. I used to conceive of the picture first and then look for a good place to take it, but now I seem to find the backgrounds and place a child in them, hoping for something interesting to happen.

In the last picture I took of the three of them together, they are actually just blurs, attenuated by the heat waves from a quenched bonfire. In the foreground the focus is on some determined little mongrel flowers.

Judging by the scrutiny we were subjected to over the last few years, I expect much will be made of the distance springing up in the pictures between the children and me. But, in fact, what has happened is that I have been ambushed by my backgrounds.

They beckon me with just the right look of dispossession, the unassertiveness of the peripheral. These are the places and things most of us drive by unseeing, scenes of Southern dejection we’d contemplate only if our car broke down and left us by the verdant roadside.

I like to think that these are the kind of pictures Eugène Atget would have gotten if he had pivoted his camera away from the monuments and toward the unalluring underbrush. In fact, sometimes I do just that: under the dark cloth I rotate the camera on the tripod and watch the randomly edited scenes pass across the milky rectangle.

But it’s not that they are easy, to take or to look at. Compared to the family pictures, which had the natural magnetism of portraiture, these are uncompelling. Unlike the stare of a self-possessed child, these pictures will not draw you across the bleached parquet.

They’re a little scary that way. The family pictures seemed to strike a powerful chord in people and it’s a chord I could keep plucking as long as I have children and film. But here are a few of the landscapes: see what you think.

Love from everyone.

August 29, 1994, Bequia, St. Vincent

M—

I’ve had you on my mind all these weeks. Why? Because I’ve been taking hundreds (3? 4?) of pictures—and half of them are family pictures. Up close. That kind of blows the theory I wrote to you about the diminution (in number and importance) of the recent family pictures, doesn’t it? Thinking about the landscapes more as an extension of the family pictures than a replacement seems more accurate. After all, they spring from the same source.

xxx to you

August 30, 1994, Bequia, St. Vincent

M—

Thanks for faxing back. I picked it up this morning on my way back from the village clinic. Now that was an experience! I was a little daunted by the line that had formed by the time we got there (8:15, after a 1/2 mile walk down from the cliffs) . . . but our connections were good and the local store owner interceded for us. It turns out Emmett has a ruptured eardrum and an ear infection. He also has a marriage proposal from a toothless 80-year-old widow who insisted, patting the bench next to her, that he sit there wedged up against her. I was happy to give him away to her, I said, provided that she had a big house and we could all come and live with her. She seemed quite pleased with this arrangement and stroked his brown shoulder and sang bold songs to him while we waited. As we left after the appointment, I told her that he was damaged goods and she deserved better. (But if she’d had a big house I might have thrown Larry in to make up for the bad ear and sweeten the deal.)

I love it here. There’s a line in Turgenev’s Virgin Soil . . . it’s a suicide note, and the entire note is “I could not simplify myself.” I think that might have been my note if I had not come here.

Just the picture-taking thing: it’s all different now. I think I was working out my next step when I saw you in Lexington, and the landscapes we looked at were the first sign of new growth. Now I’m freely moving back and forth between the family pictures, some new work with Larry, some self-portraiture and the landscapes. The boundaries of all these projects seem more permeable now—they all feel like family pictures in a way.

The pictures of the children, and, to a degree, the pictures of Larry, come in moments of epiphany, serendipity. The landscape work is a lot more cerebral, less dependent on chance. The landscape is teasingly slow to give up its secrets. There it is, sprawled across our vision, always out there. Just the way the children were there, underfoot, seeming to be so accessible.

But neither of them proved to be: to the contrary, their complexity was Gordian. I wasn’t sure how to puzzle it out. I suppose I could have tried to untie it or cut it, like Alexander. But I chose to look at it, and photograph its defiant intricacy.

Working on the landscapes, I came back to the elemental, basic presentation; the solitary tree, the light-struck noonday field. As a consequence, they are often simple pictures, possessed of a kind of naiveté that I thought I had lost. I am less afraid of that naiveté: as Niall once remarked to me, naiveté in art is like the digit 0 in math; its value depends on what it’s attached to.

I still want to make a beautiful image. Since I’ve been here I’ve read a piece by Dave Hickey in which he applauds the subversive power of beauty. In this article Hickey argues for the use of beauty as a persuasive agent in conveying the artist’s agenda. I find this more Ciceronian approach between agency and agenda far more appealing than the Modernist’s distinction between form and content.

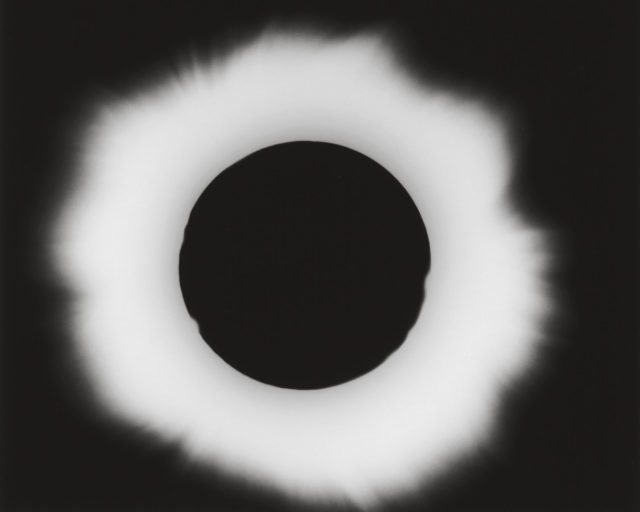

I have found tangible evidence that within this life’s sweet tedium reside certain truths: that nothing attains maximum beauty until touched with decay, that the vulgar and the miraculous can be one. For years I’ve passed this evidence by: it was invisible through overfamiliarity.

I look now at all hours, but I mostly find the pictures in the marginal times of day, that hour of mystery before night. Toning them, and usually printing them dark, gives them more of the feel of the actual moment: in some cases impenetrable and mysterious, but in others crazed with tawny light.

The landscapes need to be seen in context. They are intended to be every bit as revelatory and celebratory as the family pictures. Michael Lesy once wrote that if a picture is taken out of its context of life and love, it will appear enigmatic and void of meaning. But, when restored to its narrative and iconographic context it becomes “the capstone of a pyramid whose base rises from the human heart.” These landscapes belong with the family pictures; they provide the background and the history and the scale. They give them dimension. If the family pictures are flashes of the finite, these landscapes offer them residence in the languid tableaux of the durable.

Warm love,

S.

September 14, 1994, Lexington, Virginia

M—

It occurs to me that since this is an article on process, I might as well tell the rest of the story. It’s true that I shot four hundred negatives. But fifty percent of them were ruined by the humidity. It turns out that the gelatin layer was soft because it was fresh film.

When I got ready to develop them, I noticed that they were stuck together in little pinprick areas and I teased them apart. But the friction of the bond separating caused a microburst of electricity. They look as starry as the night sky. Most of them weren’t good pictures anyway; my usual 2% success ratio was in play, but there are a few beauties that were ruined.

This is process, isn’t it?

Love, as always,

Sally

Click here to find Immediate Family on the Aperture Foundation website.