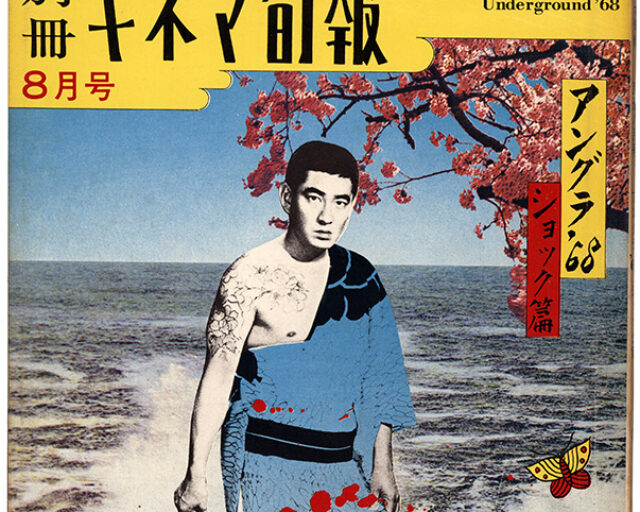

A Japanese Photographer’s Encounters with Natural Disasters

Eight years after a devastating tsunami, Lieko Shiga investigates Japan’s haunted landscapes.

Lieko Shiga, from the series Human Spring, 2018–19

Death, like the tsunami about to usher it ashore, moves toward her. She is standing unaware outside a grocery store in the city of Natori. She can’t see the ten-foot waves cresting in the Pacific Ocean. She doesn’t feel the seismic plates shifting, scraping, subducting, or lifting the sea floor approximately eighty miles away. All she knows is what they told her: tsunamis do not happen in Kitakama village, where the sandy coastline near her studio runs straight and narrow. Then the Great East Japan Earthquake hits on March 11, 2011, the first blow of the “triple disaster” that will claim more than 15,500 lives. But photographer Lieko Shiga, alone in a parking lot, twenty miles from the village, doesn’t realize this yet.

Courtesy the artist

When the aftershocks subside, Shiga runs inside the store. Everyone is safe. She returns to her car and drives toward her studio—a prefab trailer nestled among the magical grove of pine trees adjacent to Kitakama beach. Her boyfriend calls, unscathed but upset. “Please don’t go to your village,” he says, having heard a tsunami warning issued over the radio. “It’s coming.” But she keeps driving until, suddenly, she sees it. The sea stretches out like a long, dark coffin. A massive, brown wave filled with debris barrels toward her white Mazda. She reverses quickly and races in the opposite direction, keeping one eye on the rearview mirror as the waves close in behind her. Along the road that leads inland, she passes a mother with her son walking calmly and obliviously. Shiga doesn’t know them, but she urges them into the car, where they wait out the snowy night together parked in front of Natori City Hall.

Courtesy the artist

I first heard Shiga recount parts of this story in summer 2014. We were in Tokyo, and she was pregnant with her son, Shiita. As she recalled the nearness of the waves, her protruding belly came to signify her survival. She embodied the notion that proximity to death conversely breeds proximity to life. Similarly, hearing the tsunami described as more devastating than war, she told me, made her identify that event as the first “super real” experience of her life. Born in 1980 and raised in a suburb of Okazaki in Aichi Prefecture, where the neighboring Toyota plant and assorted manufacturing facilities employ the majority of the local workforce, she always perceived her immediate environment as an empty stage, with props and puppets acting out scenes before her eyes. But in the aftermath of the disaster, she “can finally feel what’s happening in the world.” This sensation comes to bear in her work. “I can imagine quite clearly now. I can trust my imagination. And it’s not only about dreaming; I’m connecting.” In 2008, Shiga moved to Kitakama in Miyagi Prefecture, motivated in large part by the promise of connection. A residency in nearby Sendai two years earlier introduced her to this place—its peculiarities, its agrarian roots, its strong and intoxicating natural landscape. She was immediately entranced. “I wanted to jump inside the photographs I was making here,” she said. After seven years in London, where she studied photography at Chelsea College of Art and Design until 2004, followed by two years in Berlin and residencies in Singapore and Brisbane, Shiga boomeranged back to Japan for good. Kitakama had emerged as “the place I’d been looking for all along.”

Courtesy the artist

How could this village, situated in the “backwater” region often regarded as “old Japan” because of its slow pace and rural lifestyle, be part of the same country she called home? Like many people, her knowledge of northeastern Japan—six prefectures collectively known today as Tohoku (meaning “northeast”) but formerly called Michinoku, meaning “end of the road” or “back roads”—derived almost exclusively from Kunio Yanagita’s The Legends of Tono (1910). But that folkloric account represents one academic’s journey across Tohoku, she is quick to point out. He purportedly spent little time in Miyagi Prefecture before returning home to Tokyo. Shiga’s initial impression of the area as silent, minimal, and imbued with a punk spirit also diverged from Yanagita’s account. Intrigued and determined to discover this unusual place for herself, she understood that as an outsider she needed to establish her studio there.

To simultaneously announce her arrival, in January 2008, and ingratiate herself among villagers, Shiga passed out flyers that read: “Pleased to meet you. My name is Lieko Shiga. I have rented a space in the pines next to the Kitakama Pool … I am a photographer, and I usually travel around to various places and take photos. This will be my center of activities for the new year…. I will do my best to serve you.” She became the local community photographer. In this role, she documented everything from baseball games to town hall meetings, as well as festivals and ceremonies on the verge of dying with members of the aging population. She made portraits that villagers could give to family members or use for their own funeral services. As word spread, people began to visit her studio out of curiosity. Soon she began recording their oral histories, collecting information about them, the local environment, the economy, and the history of the village. A complex portrait of Kitakama consequently emerged, leading her to believe: “Japan is in Tohoku.”

Courtesy the artist

Four days after the tsunami hit, Shiga returned to her studio for the first time postdisaster. It was gone. She couldn’t even locate the plot of land it once occupied because sand stretched across the forest like a massive tatami. The home she rented nearby had also washed away. “What does it mean to no longer be able to live on your own land?” she asked herself. By that point, fifty-three of Kitakama’s 370 residents had been confirmed dead; another seven were declared missing. Shiga had photographed all of them. How do you pick up the pieces of projects interrupted by disaster and death? Can you continue? Do you start over?

She arrived at an answer quickly, which she articulated in an email to worried friends and family on April 5, 2011: “What I feel compelled to confirm with my entire being is that what I started … is not over at this moment. If anything I have done in Kitakama up to now was rendered meaningless by the disaster, it was just the things that could be washed away.” But she didn’t miss her camera. In fact, she struggled with feelings of disappointment with the medium of photography—years earlier, it had allowed her to discover her existence, but now it seemed empty. And yet, charged with a sense of responsibility as the community photographer, she borrowed a camera to record her neighborhood. The choice to remain busy and connected, to serve this place as a documentarian, defined this period in her life. It informed her decision to voluntarily live in temporary shelters for three years rather than move in with her boyfriend and his family, whose home was not damaged. It justified her participation in the cleaning of found photographs at the community center. It gave her a reason to live. It alleviated pain. It allowed her to forget what happened. It allowed her to remember.

Courtesy the artist

Shiga has since realized two major projects; both embrace the past and explore notions of memory. In 2012, she released Rasen Kaigan, a body of work rooted in Kitakama that concerns the landscape—its physicality, its mythos, its history, and human intervention into it—and constitutes a collaboration with local residents. Last year, she revisited and updated a project, from 2008, called Blind Date, which features photographs of couples on motorbikes in Bangkok. The tsunami claimed most photographs made prior to March 2011 that Shiga envisioned utilizing in these series, but some files stored elsewhere remained accessible. Trusting that the pictures had been left behind for a reason, she incorporated them into new work. In the case of Rasen Kaigan, she also felt it necessary to reconceptualize the project on account of the tsunami. But the disaster itself would not become her subject; it was one moment that violently punctuated her extended engagement with the community and the land of Kitakama. What she needed to express was how the tsunami had entered her body.

Courtesy the artist

Shiga has alternately referred to herself as a camera, a vessel, and a medium. In all of these descriptions, photography takes a physical form. This perspective stems from her training in dance, which ended abruptly at the age of eighteen. Aware and deeply self-conscious of how her body was rapidly changing, Shiga abandoned dance for photography in high school, a decision she later questioned upon encountering the experimental, expressive work of Pina Bausch. However, she ultimately found she could tap her interest in performance and physicality as a photographer. This often involves pushing her body into the frame, whether literally or figuratively. In Rasen Kaigan, one self-portrait exemplifies this idea: map showing the relationship between photography and myself (2012) depicts her carving concentric circles into the sandy beach with the root of a pine tree. But arguably the most personal incursion in the series occurs in the photographs of white stones, something Shiga likens to mirrors that reflect memories of faces, animals, or trees found in Kitakama. Upon viewing the exhibition of Rasen Kaigan at Sendai Mediatheque, Miyagi Prefecture, in late 2012—where prints were displayed as a dizzying gyre in a darkened room—visitors responded to the sight of these enigmatic stones as she had. Many brought their own associations. Everyone saw Kitakama. Critic Minoru Shimizu, who took the minority position when he dismissed her photography as the stuff of “B-grade horror,” declared the installation “cleverly constructed as a stage device in which the acts of recalling and mourning alternate.” Former Sendai Mediatheque curator Chinatsu Shimizu said the exhibition resembled a funeral, with prints angled upright like tombstones in a cemetery, and the visitor experience akin to bon odori, a traditional style of dancing during the Obon festival in which people dance in circles to mourn the dead.

Courtesy the artist

In Spring Snow (1969), Yukio Mishima writes, “There is an abundance of death in our lives. We never lack reminders—funerals … memories of the dead, deaths of friends, and then the anticipation of our own death.” The proliferation of death, alluded to in Rasen Kaigan, spurred Shiga’s new body of work, Human Spring (2018–19), the third part of a trilogy that includes Rasen Kaigan and Blind Date. In 2012, while living at an evacuation center near Kitakama, Shiga found herself surrounded by mortality. Two neighbors, residing in the apartments that flanked hers, died by suicide during her stay. They were the only individuals there to fall victim to what the Reconstruction Agency of the Government of Japan officially termed “disaster-related deaths.” Classified as indirect damage caused by either physical or psychological stress, such casualties triggered by the earthquake and tsunami emerged collectively as a crisis. Many of those affected, including one of Shiga’s neighbors, were farmers who resorted to suicide because their oversalinized crops could not be sold.

But the farmer whose story anchors Human Spring is S-chan (whose name has been changed to protect his family’s privacy). A native of Kitakama, S-chan grew Chinese cabbage and melons on land owned by his family for many generations. In the late 1980s, a government-supported initiative to stimulate further agricultural production in Tohoku—an area historically cursed by famines and harvest failures—allowed him to install a greenhouse. Eager to see how his crops would perform in this new environment, S-chan visited his farm obsessively until one morning, when he discovered that everything had died overnight. He eventually recovered and revived his business, but the seed of depression had been planted inside him. It germinated for decades.

Courtesy the artist

Shiga met S-chan years later, in winter 2008. He often stopped by her studio during his morning walks to the beach. They exchanged pleasantries and became friends. But within a few months, Shiga recognized something odd about his character, something that everyone noticed but no one acknowledged out loud. In spring, about forty-eight hours before the cherry blossoms bloomed, S-chan transformed. His cheeks turned red. He never slept. He drove his tractor around town in the dark. He talked incessantly. According to Shiga, S-chan’s particular strain of mania always coincided with the change in seasons; his “super high” marked the onset of spring, which arrives so suddenly in Tohoku that “the body must respond before the heart,” Shiga said. “He was the spring itself.”

Immediately after the tsunami, Shiga and S-chan spent three months in the same temporary shelter staged inside a local middleschool gymnasium—a location referenced in Human Spring. His strange behavior continued there. He walked around clutching a Jizo statue, like a child with a stuffed animal. He visited the beach often to confer with the ghosts because, he claimed, they were lonely. Every morning, he flung open all the curtains at sunrise to announce the arrival of a new day. Though this annoyed practically everyone at the shelter, they were so charmed by S-chan’s idiosyncrasies and positive energy that “springtime mania infected them, too,” said Shiga.

Courtesy the artist

In 2013, soon after the suicides in the evacuation center, S-chan succumbed to cancer. Shiga couldn’t help but draw a parallel: one death prompted by disease, two deaths instigated by societal and financial pressures, all of the men victims of the Heisei depression—a reference to the Imperial era during which they died—and all connected through her. As time passed, she kept thinking about their final moments and thoughts, the state of their corpses, and their potential reincarnation. After these tandem deaths, Shiga confronted the fragility of her own existence when diagnosed with hyperthyroidism. She lost control of certain faculties, she sensed S-chan’s manic spirit pulsate through her every time her metabolism accelerated, and she started to channel this energy into Human Spring.

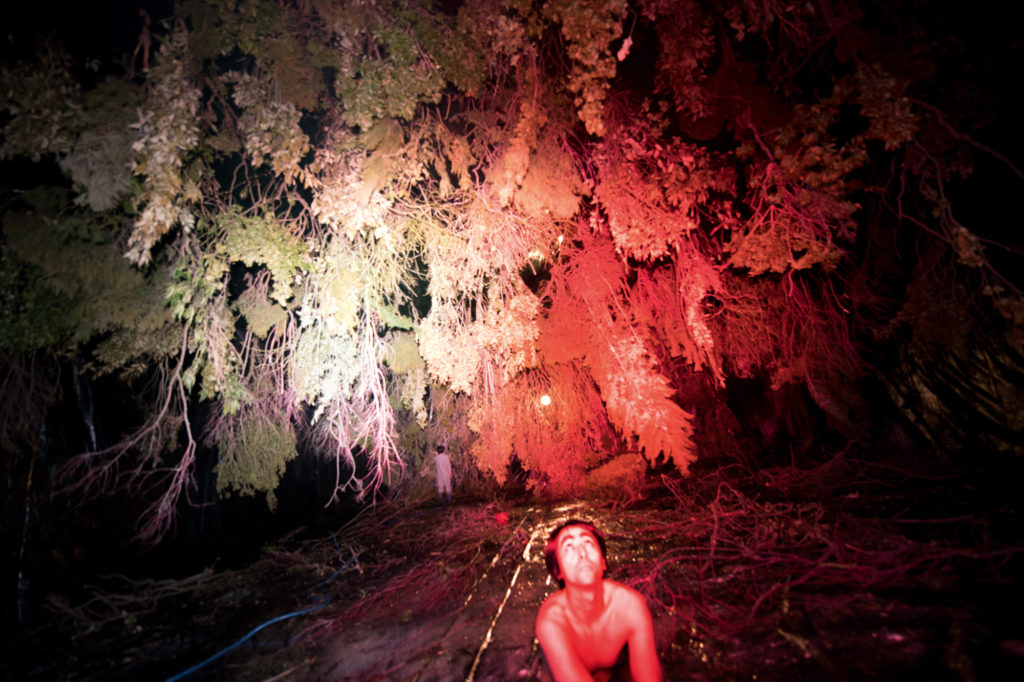

For Shiga, the process of generating her latest series began by positing simple but expansive questions: What is the history of human expression? What is inside the human body, and how is it connected to the earth and to society writ large? Such queries demanded extensive research and fieldwork, which, along with the active participation of her subjects, are mainstays of Shiga’s practice. She draws inspiration from everywhere: friends, dreams, films, dance, news events, nature, literature, mythology, personal experience. The concept of spring—as the season when cherry blossoms both bloom and die, as a period that has defined such historic uprisings as the Prague Spring and the Arab Spring, as a physical movement—serves as an organizing principle. Sometimes these varied influences and ideas yield highly controlled surrealistic work, from sculptures made in her studio that evoke Mike Kelley’s Kandors series (1999–2011) to a choreographed scene in the landscape of a suspended forest, yet her process never involves digital manipulation.

Courtesy the artist

But in alignment with Shiga’s own delicate physical state, Human Spring reflects and arises from discomfort and intentional disorder. An image of the off-kilter horizon, made from an airplane window, encapsulates the imbalanced, dualistic spirit of the project. She also wrestled with personal and national trauma by photographing in Fukushima Prefecture, where she focused on the ghost town of Futaba (population zero), located five miles from the Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, which released radioactive material into the ocean, soil, and air in 2011. And unlike in previous series, Shiga worked with many anonymous people and sought unfamiliar locations while making these images. These circumstances destabilized certain preconceived ideas of the project and even disrupted the previsualized images she sketched out on paper, forcing a loss of control, much like the megathrust earthquake shifted Earth’s axis and threw off its orbit. Only under such uncomfortable conditions, she claims, could she make Human Spring.

Conceived as a series of personal pictures, Human Spring originally bore the title S-chan’s Spring until Shiga realized that his story represented a set of more universal, interconnected social, environmental, and economic fault lines running just below the surface of things in Japan. S-chan’s depression felt deeply intertwined with the development of the Heisei era, which commenced in 1989 not long before the economic bubble collapsed in the early 1990s, around the time his greenhouse was installed. Broadly defined by its excess and emptiness, the Heisei period will come to a close on April 30, 2019, when the emperor abdicates his throne. In his 2017 book Ghosts of the Tsunami: Death and Life in Japan’s Disaster Zone, journalist Richard Lloyd Parry observed that the country has been “adrift, becalmed between a lost prosperity and a future that was too dim and uncertain to grasp” during much of the Heisei era; though the disaster, in 2011, had the potential to jolt “Japan out of the political and economic funk into which it had slithered,” this has not occurred. Perhaps the presentation of Human Spring at the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum, in spring 2019, scheduled to overlap with the end of the Heisei era, will usher in a new wave of reflection, with images that defy any sense of calmness and complacency associated with the past three decades.

Courtesy the artist

As Tohoku continues to recover and rebuild, the land still registers wounds of contamination, devastation, and depopulation. “Everywhere is the shadow of death,” as Rachel Carson wrote of a fictional town sprayed with DDT in Silent Spring, her classic 1962 book about the effects of toxins in the environment; this valuation could apply to many villages in northeastern Japan today. Citing Carson’s influence on Human Spring, Shiga acknowledges, “If I want to capture what’s happening when we’re alive, I have to think about death.” It is omnipresent, it is internal. Ideas about life and death swirl inside her constantly and quickly, such that “her mind is a kind of ocean,” as her publisher Tomoki Matsumoto put it. The tsunami that seeped into her body now spills out in her work. And one side effect, Shiga says, is that “I am living with a lot of dead and I may be a ghost.”

Read more from Aperture issue 234, “Earth,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.