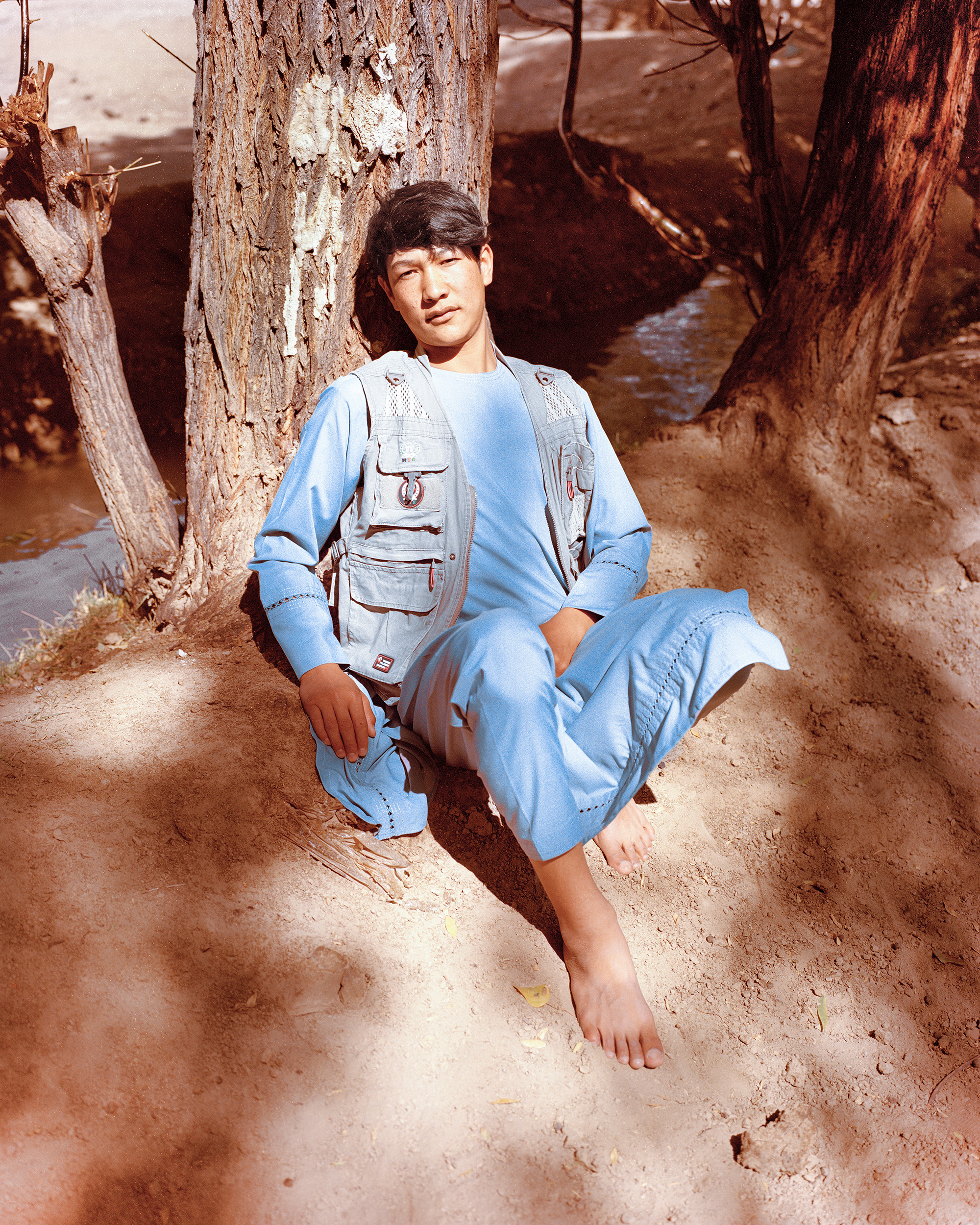

Hashem Shakeri, Staring into the Abyss, Afghanistan, 2021–ongoing

On August 15, 2021, Kabul was in chaos. Photographs of desperate crowds at Hamid Karzai International Airport and refugees packed onto US military planes were shared widely around the world as the Taliban encircled the city. Taken three years after the end of American occupation, Hashem Shakeri’s The Fall of Kabul is a far quieter—and ultimately more disconcerting—image: the photograph shows three young Taliban soldiers, scarcely older than teenagers, looking listless as they guard the dusty top of Wazir Akbar Khan Hill. Clad in sandals and holding Kalashnikovs, they make a pathetic picture of one of the world’s most repressive, fundamentalist regimes. These rough-shod provincials working for starvation wages are among the many Afghans betrayed by their government in Shakeri’s series Staring into the Abyss (2024). Kabul may have long since fallen, but these photographs offer a rare glimpse at how the country slides further still.

Based in Tehran, Shakeri is used to taking pictures in hard-to-reach places, but he’s not a documentary photographer in the conventional sense. Since 2019, when his eerie photographs of derelict public housing estates far from Tehran’s center were published in The New Yorker, he has mostly received international attention from art and fashion magazines. Perhaps that’s because, while Shakeri aims his lens at appalling social issues, his technique is extraordinarily refined. These are beautiful images of ugly truths, and for any photographer, that’s a very difficult needle to thread. Taken with a medium-format camera and 120 film several stops overexposed, an image of unfinished apartment blocks rising beyond mountains of industrial waste, for instance, assumes a searing atmosphere of desolation. Even the vivid, artificial colors of a child’s swing set or a group of oversized pinwheel sculptures do little to enliven the bleached and barren landscape.

Shakeri began experimenting with overexposure in 2018 while shooting in Sistan and Baluchestan, a large but remote Iranian province on the border with Afghanistan. In his Book of Roads and Kingdoms, an atlas of the Muslim world, the tenth-century Persian geographer al-Istakhri described the region as a “fertile” land full of green, irrigated fields along the Helmand River. It was a cradle of ancient civilization stretching back to the settlement of Shahr-e-Sukteh around 3550 BC. Now, the ruins of the neolithic “Burnt City” sit in a drought-riddled wasteland plagued by conflicts over rights to Helmand water. The photographs in Shakeri’s An Elegy for the Death of Hamun (2018) feel appropriately parched, as the people in them wander through fields and ravines lacking any sense of warmth or moisture. Crucially, however, Shakeri gives us glimpses of humanity, like a five-year-old boy dangling from an improvised rope-swing along a dry riverbed. If they locate a certain sublimity in scenes of ecological devastation, these photographs also empathize deeply with the people—mostly members of the oppressed ethnic Hazara minority—who’ve been left behind.

Staring into the Abyss was perhaps Shakeri’s most difficult project to date. As an independent photographer without institutional backing, he was repeatedly threatened by government agents—even as Taliban soldiers agreed to pose for him. “The situation was highly volatile, and everyone lived in uncertainty. I tried to reflect this fluidity and ambiguous, uncertain perspective in my photographs,” he says. There’s no violence on display, but scant sentimentality either. Rather, Shakeri shows the texture of daily life in a place the rest of the world has seemingly forgotten. Soldiers crack open and share a watermelon on the pavement; a boy plays with an albino pigeon in an auto body shop; an assortment of pink clothes and homewares for sale gather dust by the roadside.

While many of the images are overexposed, the series is also a departure in terms of Shakeri’s process. In several photographs, he uses new techniques to conceal their subjects’ identities from the Taliban: a photograph of an underground girls’ school, framed so we only see its pupils’ hands, has been doubly exposed, as if shot through curtained glass. Another depicts a ten-year-old refugee charging his family’s solar panel in a Kabul park, but solarized so that only the panel itself is fully visible, shining white against a field of fire. Shakeri says the photograph inspired the series title, a reference to Nietzsche’s proclamation that “If you gaze for long into an abyss, the abyss stares back at you.” But it seems especially true of another haunting, black-and-white image: taken with flash at twilight, it shows ruins in the shadows of the niche that once held the ancient and monumental Bamiyan buddhas, destroyed by the Taliban in 2001. In the wake of violence, their absence has become a yawning void.

Courtesy the artist

Hashem Shakeri is a shortlisted artist for the 2025 Aperture Portfolio Prize, an annual international competition to discover, exhibit, and publish new talents in photography and highlight artists whose work deserves greater recognition.