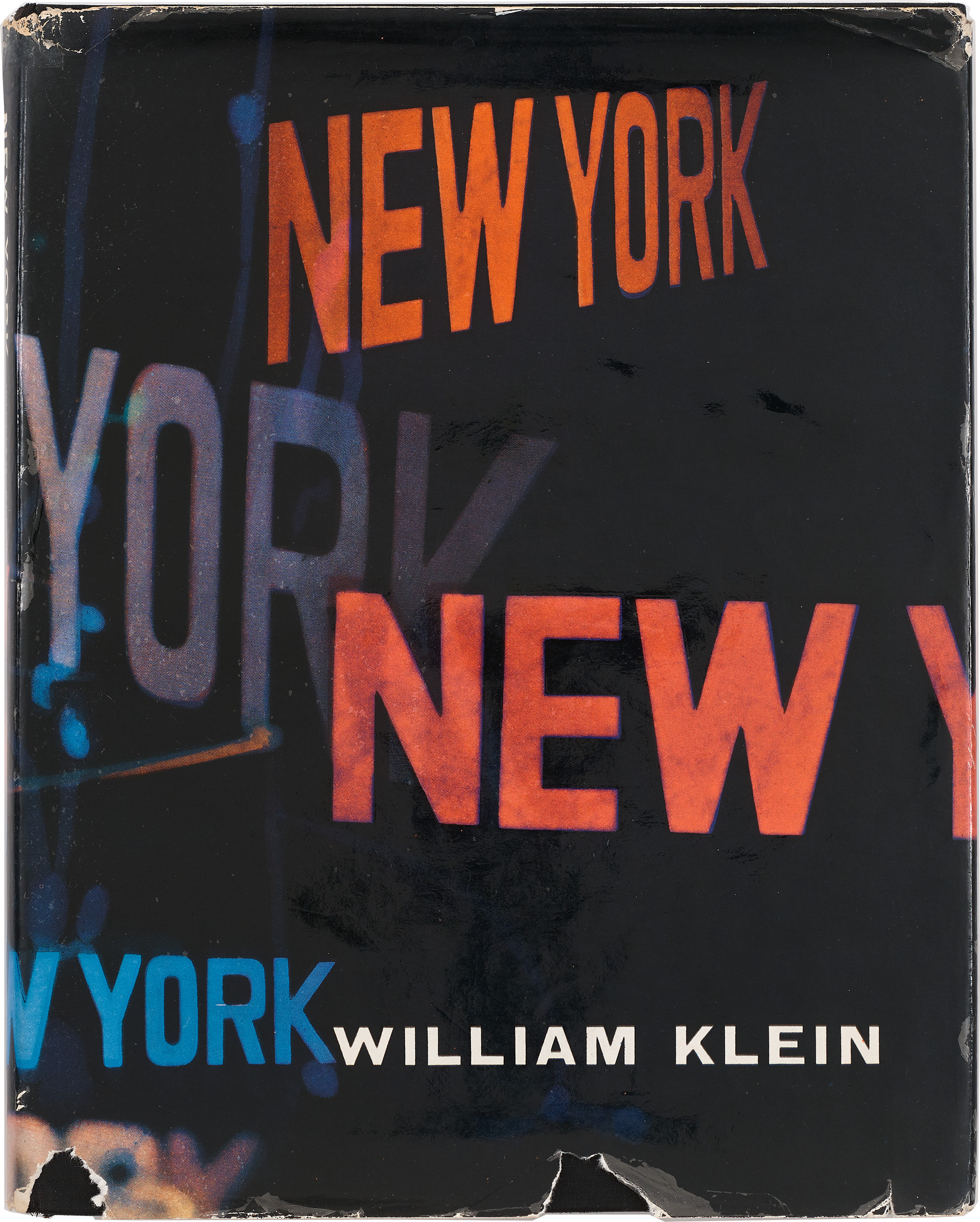

Cover of William Klein, Life is Good & Good for You in New York: Trance Witness Revels (Photography Magazine, 1956)

Faced with the complexity and contradiction of New York, photographers tend to take a position, to form a coherent response, especially when making a book. Nearly all New York photobooks do this, from Berenice Abbott and Elizabeth McCausland’s Changing New York (1939) and Daido Moriyama’s 1971/NY (2002) to György Lörinczy’s New York, New York (1972) and Ken Schles’s Invisible City (1988). But what if one doesn’t have a clear position? Since a book is built up from individual images, what if each photograph is a singular expression and they just accumulate, leaving the sense making up to the viewer? These are the questions provoked by William Klein’s bewildering opus Life is Good & Good for You in New York: Trance Witness Revels, published in 1956.

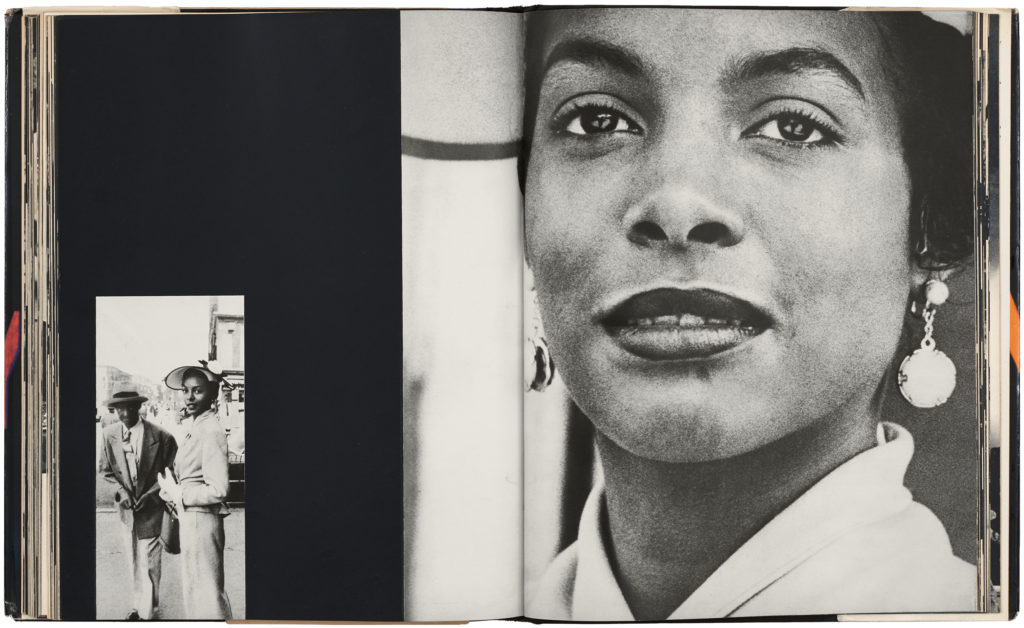

Art history tends to reduce Klein’s New York work to a handful of punchy and gritty street shots, but the book itself always surprises. For every picture of anarchic kids clowning or billboards exhorting, there are as many visions of tenderness, elegance, and affection. Each seems to be made with conviction, but there is no point of view that unites them all. In fact, Klein’s book signaled a break with the modernist idea that an artist should even need such a thing as a unified position.

Collection of Vince Aletti

His teeming vision emerged at the onset of Pop, a movement that would quote, mimic, and mirror back the contradictory iconography of postwar popular culture. Klein pioneered for himself a kind of hyper-photography, bouncing between genres. In this one book he is historian, urban geographer, sociologist and anthropologist, Weegee-like newshound, cool Walker Evans inspired surveyor of the urban fabric, high-society photographer, fashion visionary, and even abstract artist.

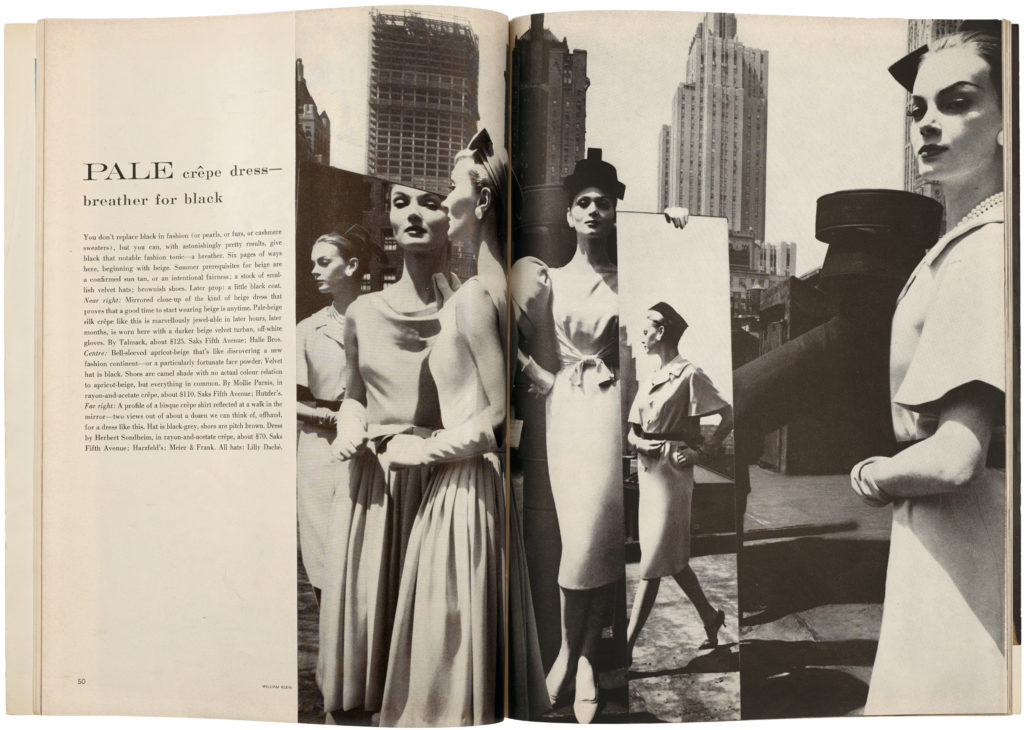

Indeed, fashion and abstraction were key to the book’s genesis. Born into a Jewish family on the edge of Harlem in 1928, Klein left the United States for Europe, in 1946, to become a painter. He returned in 1954 at the invitation of Alexander Liberman, art director at Vogue. In Paris, Liberman had seen a show of Klein’s abstract photographs and paintings. Klein was not trained in photography but had endless curiosity. At first, Liberman gave him still-life assignments. Shoes, hats, the season’s fabric swatches. They lent themselves to inventiveness, and Klein gained a reputation for stylish problem-solving. He would soon photograph Vogue’s models with the same creative verve, leaving the studio and taking them out into the unpredictable world outside.

Liberman also bankrolled Klein’s wish to shoot the streets of New York with complete freedom. He developed and printed his photographs at night, transforming his errors of exposure, focus, and motion blur into expressive devices. With the new photostat machine in the Vogue office, he made high-contrast copies of each image in multiple sizes and used them to create a dummy of the eventual book. Klein did his own layout and the jacket design. He also wrote the hilarious and insightful captions, which were printed as a separate pamphlet, attached to the book’s spine by a cord.

Collection of the author. Photographs by Fabrizio Amoroso

Every spread has a different arrangement, and the book overall is impossible to remember. With each viewing, the emphasis falls somewhere new. For me, of late, the energy of Klein’s many Harlem photographs has my attention. Throughout his career, Black experiences have been a key thread (he went on to make groundbreaking films about Cassius Clay, Eldridge Cleaver, the 1969 Pan-African Festival in Algiers, and Little Richard). Klein’s captions speak clearly of Black resilience in the face of white racism. His Harlem images range from the almost chaotic to the stately, but he is always present to his subjects. Never attempting to be invisible, Klein is unmistakably part of each situation—interacting, collaborating, sharing, and celebrating. There’s nothing voyeuristic, and certainly nothing objective, about his images. These are willfully immersive photographs, and all the richer for it. New York is performed as much as documented, with human life a constantly improvised theater.

To the purist defenders of documentary and fine-art photography in the United States, this was all deeply off-putting. Only recently has the country come to appreciate Klein’s artistic achievement and global influence. At the time, no U.S. publisher would touch Life is Good & Good for You in New York. It was tumultuous and wild, with swerving bebop rhythms of editing and no calming white borders. The most adventurous American photobook to get published in the 1950s was probably Roy DeCarava and Langston Hughes’s The Sweet Flypaper of Life, from 1955. Klein’s book had ten times the photographs, no narrative, and a jumble of styles. Back in Paris, it was the young upstart editor Chris Marker who persuaded Éditions du Seuil to issue it, with co-editions published in London and Rome. Today it tops many lists of the most influential photobooks.

I have never understood Klein’s views about New York, and this has never bothered me. One can see in his book a premonition of the city’s future urban hell, but of resilience and reinvention too. Sixty-five years on, it remains a vision against which the city can measure itself.