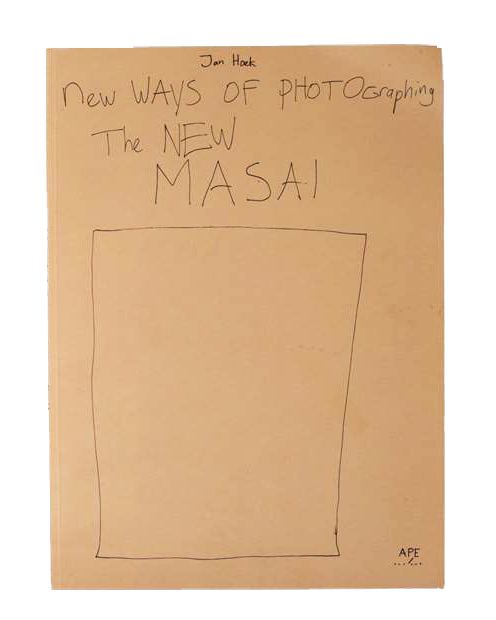

The cover of Jan Hoek’s New Ways of Photographing the New Masai (Art Paper Editions, 2014)

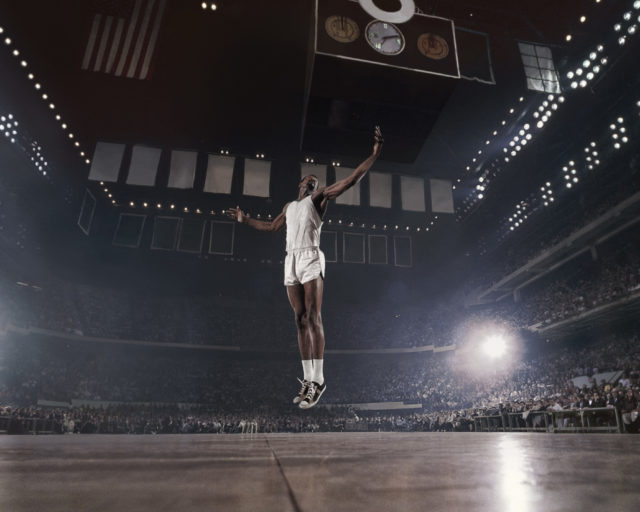

Dutch photographer Jan Hoek’s New Ways of Photographing the New Masai (Art Paper Editions, 2014) has the appearance of a handwritten school notebook. Its spine and cover are adorned with a mishmash of spidery letters that spell out the title in an irregular and child-like script. The book scarcely contains any writing to contextualize the project and define for readers what is meant by “old” versus “new” ways of photographing this traditionally semi-nomadic tribe of Kenyan people, save for a very small image of leaping tribesmen that appears on the book’s first page. That image is uncredited, and appears to be a fairly conventional travel photograph in which the Masai are photographed jumping skyward in traditional red costume while grinning for the lens. Hoek’s website offers some more information:

“The Masais are always photographed the same: jumping in nature while wearing traditional outfits and jewellery. Almost like it is a group of animals. But more and more Masai start to live in towns and buy their first Nikes and put mobile phones in their stretched ears. Together with seven urban Masai I tried to find a new way to photograph the new Masai.”

Hoek’s book contains a series of portraits of seven Masai tribespeople, made according to what we are told are their preferences as to how to be pictured:

Filemon: “Doesn’t like: To be photographed naked.” Seuri: “Doesn’t like: To be photographed naked.” Mike: “Likes: Masais [to be] photographed in a modern way.”

We later discover only six are true Masai tribesmen, and that the seventh individual falsified his identity. His portraits are still included but appear struck through with thin black lines, so that his deception is theatrically punished, while the competence of whomever he deceived is left excluded from the record, along with the nature of the relationships and intentions that led Hoek to make this book.

The provenance of these pictures; the very reason for their having been made at all; the manner of their making; the nature of the “collaborative” relationship with the photographer; the necessity that Westerners see Masai tribesmen according to Hoek’s “new way”—none of these crucial but unstated questions—are deemed worthy of an answer. Hoek’s “New Masai” are left as protagonists and independent actors, reaching out to us (apparently) at their own behest, and ostensibly in the manner of their own choosing. The specific hopes, desires, and experiences of seven people are reduced to an itemized list that continually restates their desire not to be forced to strip naked for the delectation of a Western lens. In this way, these individuals are imagined within the confines of their role as objects for visual representation. Their lives as people are pared back to the narrow parameters of how they choose to live as images.

These seven people are left to respond to the unstated prerogatives of an artist whose virtual silence within the written content of the book confers on them responsibility for their unskilled appearance. They are rendered in poorly lit, poorly exposed, technically mediocre images, which only succeed in demonstrating their inexpert grasp of new technology. The only choices declared in the book are those of the individuals who are the subjects of images credited to Hoek as the photographer. Thus, in “addressing us” through a premise constructed so that Hoek might show his new way of seeing black bodies, these individuals take up the centuries-old mantle of the colonial subject responding to white Western preoccupations. And as in so much orientalist imagery, their bodies exist purely to serve.

There has latterly been a recurrence of pejorative photography of the black body in contemporary photobooks. Such work operates on the implicit premise of the primitivism of the Other, according to which blackness and black bodies are defined by a rudimentary existence in a premodern, mystical world. Such work depends upon this assumption in order to celebrate the vibrancy of African culture, the athleticism of the black body, or to delight in the richness and beauty of black skin. In this way, the black Other serves to alleviate the complexities of modern Western life, by offering an anachronistic alternative to white Western identity.

New Ways of Photographing the New Masai is characteristic of this growing corpus of photographs that portray the black body as “a socius without writing or the Word, history or cultural complexity,” as Hal Foster wrote in his 1985 essay “The ‘Primitive’ Unconscious of Modern Art, or White Skin, Black Masks.” Foster’s essay title underscores the way in which blackness serves as a theatrical mask that conceals a troubled white identity. His essay critiqued the decontextualization necessary to argue for an affinity between ritual tribal objects and the products of modernist art, and argued that the “primitive” is instead made to serve as a phase in the development of properly Western traditions. The primitive serves as a marker of the antiquated, the uncivilized—as a point of abjection against which Western modernity can be mapped and celebrated. Recent instances of such primitivism in contemporary photography tend to depend on the unstated clause of white Western intellectual superiority, as it is contrasted with the inherently retrograde sensuality of the black body. Such work often stresses the earthly, folkloric, and animalistic as inherent virtues of the black body and its attendant “culture,” although any contextualization of such culture is habitually excluded.

These tropes are also apparent in the work of Dutch photographer Viviane Sassen, in books such as Flamboya (contrasto, 2009), Parasomnia (Prestel, 2011), and in her latest Pikin Slee (Prestel, 2014). Made at various points in Africa and across the African diaspora, the black body is repeatedly rendered as an anachronistic contrast to Western norms, whether these are intimated by architecture, by fashion, or by other commonplace commercial goods. Sassen’s photographs are characterized by the solubility of blackness into shadow, or by its vivid difference from garish color. Her portraits incessantly emphasize the black body’s pliability and malleability in a series of strange gestures of physical contortion. In her photographs, the black body is mute, dark, gestural, and inanimate: an object made up exclusively of deep brown and black contours, pools of impenetrable shade, counterpointed by vibrant dollar-store goods, lurid paint, or the patterned effects of light and shadow.

In photographs such as Anansi (2007) or Ivy (2010), supine black bodies fuse together into sculptural oddities that are born out of a soluble relationship to the earth. And yet a certain ironic dissonance is produced by the whiteness of a shirt in shadow, or the presence of England’s Three Lions on a pair of football shorts. The antinomies of blackness and whiteness, of the earthly and the intellectual, the savage and the savior, are here overt structuring elements of the image. But such aesthetic tensions as these contrasts evoke do not trouble a long history of ethnic degradation; they reinforce it as a further instance of the theatrical acquiescence we have come to expect from subservient, primitive blacks.

Sassen’s black bodies are very frequently abstracted into postures that intimate strange bodily rituals, invoking a kind of voodoo ergonomics of spontaneous contortion, and frequently displaying acts of apparently voluntary self-effacement. They are cast as primitives, denuded of any locally specific cultural history. Sassen herself has said in an interview with Planet magazine in 2010:

“I never intend to dismantle misconceptions of the ethnic ‘Other,’ though I like to play with these preconceived ideas people in the West have. I show them things they think they know or they don’t understand (like the paint), and in that way [my photographs] indirectly provoke questions about our Western view of the ethnic ‘Other,’ which is often a very limited view.”

It is apparent from the figurative language of Sassen’s images that she plainly does not seek to “dismantle misconceptions” of the “ethnic Other,” but rather to use the black body as one among many manageable objects in a series of portraits perhaps better understood as still lifes. However, it is extraordinarily difficult to avoid the conclusion that her photographs regurgitate a limited view of alterity, which frames the black body as an object and not as an individual.

Cristina de Middel’s The Afronauts (self-published, 2012) set out to lament “the fact that nobody believes that Africa will ever reach the moon,” by re-staging images derived partly from documents she discovered recording an aborted attempt to launch a Zambian space program in 1964. De Middel’s project was photographed in Spain following her discovery, in 2009, of the story of Edward Makuka Nkoloso, founder and sole member of Zambia’s National Academy of Science, Space Research, and Philosophy. His goal was to launch a woman, two cats, and a missionary to the moon, and then on to Mars.

De Middel’s book relates an approximate version of this story from elements that are sometimes factual but often fictitious, incorporating diagrams and news stories alongside images of “afronauts” in garishly patterned spacesuit costumes sewn by her grandmother. This space program is recreated in the midst of a wild landscape that lacks any traces of aeronautical infrastructure, but contains a strangely pliant elephant. While the photographs delight in a farcical retelling, De Middel’s description for the book on Amazon.com argues that this work contains a “subtle critique” of “our position towards the whole continent and our prejudices.”

Ostensibly this is a story about the unbridled ambitions of African people, and about the injustice of their relative lack of freedom in achieving them. The absurd and implausible attempt at space flight depicted in the work underscores a profound disjuncture between Africa and the West. The riches of the slave trade provided the capital for the Industrial Revolution, without which space flight would have remained a pipe dream. The farcical tenor of the The Afronauts acts as a comic reprieve and disguises the formative role of exploitation in the production of poverty on one continent, and unbridled freedom on another.

If the past decade of extraordinary photographic production has demonstrated any one thing in the arts, surely it is the apparently inexhaustible adaptability of the photographic book to contextualize and address the specificity of an artist’s own intentions? In the photobook we have a form capable of embodying, rather than vaguely approximating, the vision of those artists who seek to use it. The recurrence of orientalist work that deals with race and its representation in such a willfully tenuous fashion suggests the spectacle of the primitive is resurgent in contemporary visual culture. This recurrence stands at odds with other meaningful advances in the general discussion around race and politics, but it also highlights the deeply contested and complex nature of the issues at hand. Just as modernity is inseparable from colonial history, so too is the abjection of “primitive” blackness inseparable from white privilege. We would do well to question the contextualization of race in such photographic work, so that we might more clearly see the white skin lurking beneath its black masks.