Lora Webb Nichols’s Mysterious Images of the American West

In the early twentieth century, Nichols made dreamlike photographs of the frontier that feel both intimate and faraway.

Lora Webb Nichols, Skyline Ranch, 1937

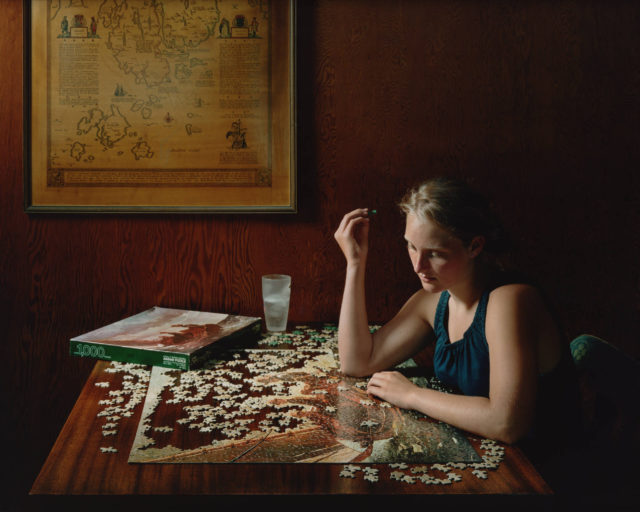

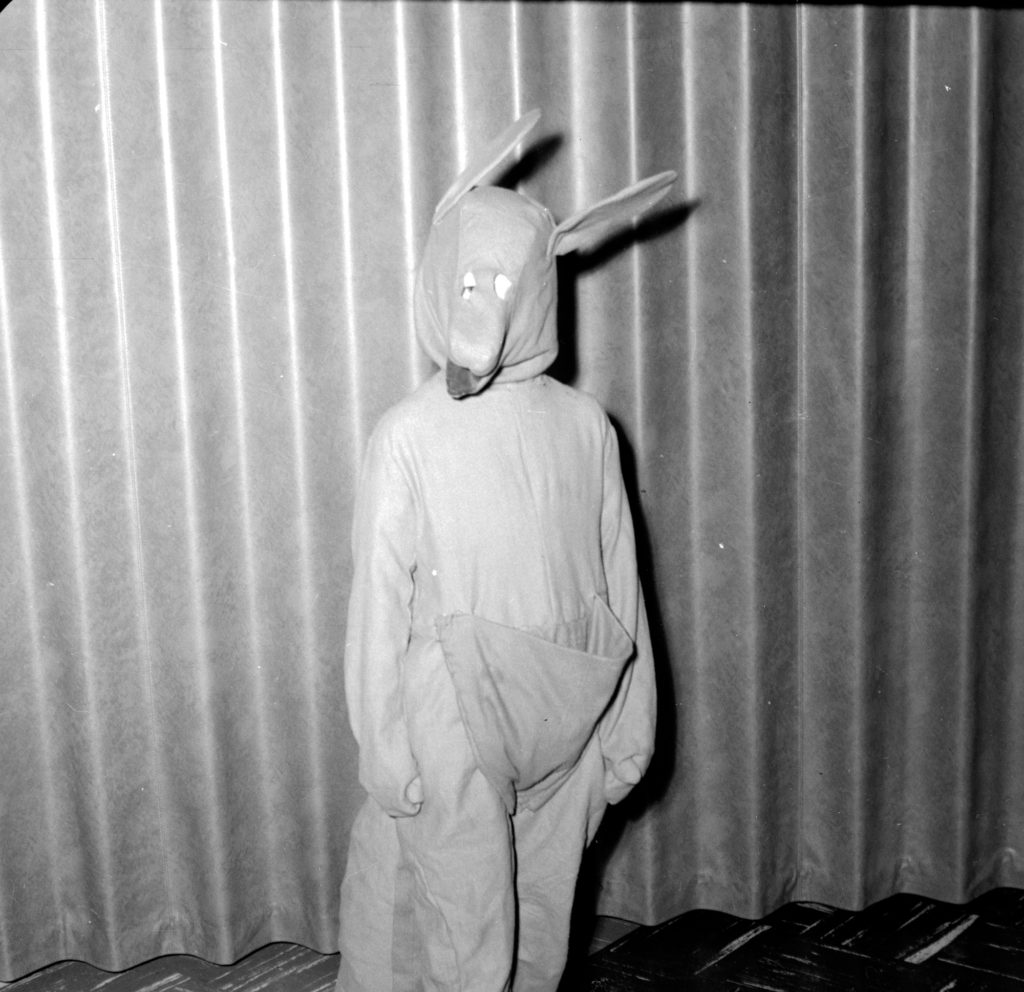

A blurry bird in a cage against a bright window, like a shadow cast, an omen. A child, ears askew in a kangaroo costume, lit up by the camera’s flash. A sapling flanked by two women, prophets or apparitions, in a far-reaching field. The American West of the photographer Lora Webb Nichols appears as visions from a dream, her breathtaking and improbable archive inspiring a disorienting reverie.

Born in 1883, Nichols was given her first camera in 1899, at age sixteen, and would spend the next sixty-some years taking photographs, many of them in Encampment, Wyoming, the frontier town where her homesteading family had settled. She would watch Encampment boom and bust with copper mining, documenting—in some cases for pay—the industry, ranch life, and the coming railroad. From early on Nichols photographed people with an artist’s intuition. She was attuned to moments not often memorialized then, and her access to quiet, private moments among women allowed her to capture, unusual for photography of the time, images of women brushing out their long hair or outstretched across a settee.

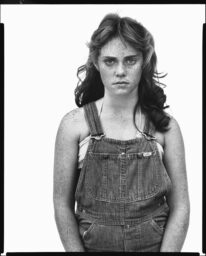

The distance between the last gasp of the Old West and the present can seem a chasm too wide to mentally and emotionally cross, even with visual aid. As the photographer Nicole Jean Hill observes in her essay for Encampment, Wyoming: Selections from the Lora Webb Nichols Archive 1899–1948 (2021), which Hill edited, archival images tend to feel remote, in part, because early film’s lack of sensitivity to light often required staging and rigidity. Despite these limitations, Nichols’s inclination toward intimate and idiosyncratic subjects and composition is pioneering. But what brings the eye to widen, then squint with recognition, is the bearing of the people Nichols photographed—how they hold themselves so openly, so honestly in her presence.

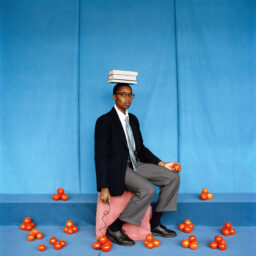

Nichols was among the influx of women who in the early twentieth-century—with the period’s newfound freedoms for women, along with the proliferation of news photographs and portrait studios—made a career in commercial photography. Nichols’s Rocky Mountain Studio, operational from 1925 to 1935, was a Kodak franchise photo-finishing business where Nichols developed film for other photographers in the area, buying negatives she liked and selling the images as postcards. She also briefly ran a local newspaper, The Encampment Echo, as well as a soda fountain where she photographed anyone who’d allow it, including the young men who came through from the Civilian Conservation Corps.

Women, in pairs and alone, recur in Nichols’s work, sharing a laugh or food, or with their animals, and a sense of Nichols’s own conviviality is often apparent in her subjects. There can be a haunting quality, too, to Nichols’s photographs that’s difficult to characterize—a glimpse of the violence and hardship of westward expansion maybe? The landscape, sublime, and our knowledge of how we’ve transformed it? That dreamlike disorientation, again. Nichols’s work is best viewed in miscellany; her portraits of people, place, and industry are inextricable.

Nichols died in 1962, leaving behind a vast archive of twenty-four thousand images that is available and viewable at the University of Wyoming’s American Heritage Center website. A natural record-keeper, Nichols kept extensive diaries that tell, beyond chipper daily details, of financial and marital struggles (she was married twice) and the difficulties of balancing business with the domestic (she had six children, four of them within six years). Nancy F. Anderson, a close friend of Nichols who’s helped to preserve her work, says she continued to take pictures and write in her diary up to her death in 1962.

All photographs courtesy the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming

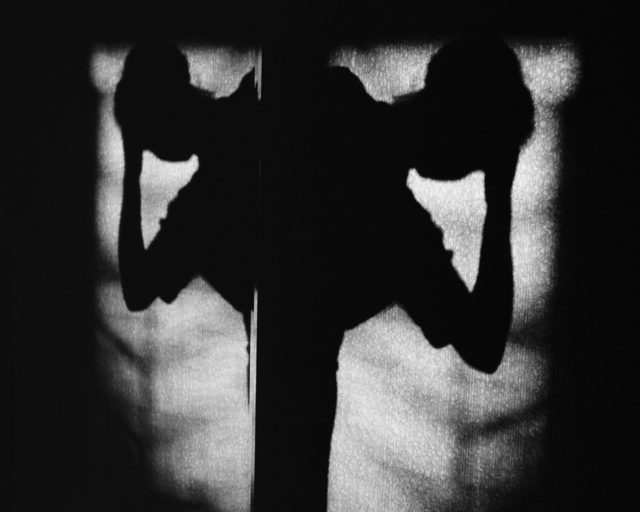

In a photograph of unflinching intimacy, her second husband, Guy Nichols, is pictured recovering from the flu during the 1918 to 1919 epidemic. Here, Nichols conjures a state somewhere between sleeping and waking, a dappled fever dream. Her husband’s vulnerable body, streaked in sunlight, is eclipsed only by the look on his face. Is it resignation or relief?

Dreaming, our minds walk while we sleep. Most vividly remembered when we wake is the lingering feeling left by our nocturnal wanderings, sometimes carried by a memorable image but not often explained by it. What Lora Webb Nichols made are astonishing and mysterious images of pure feeling, at once familiar and faraway.

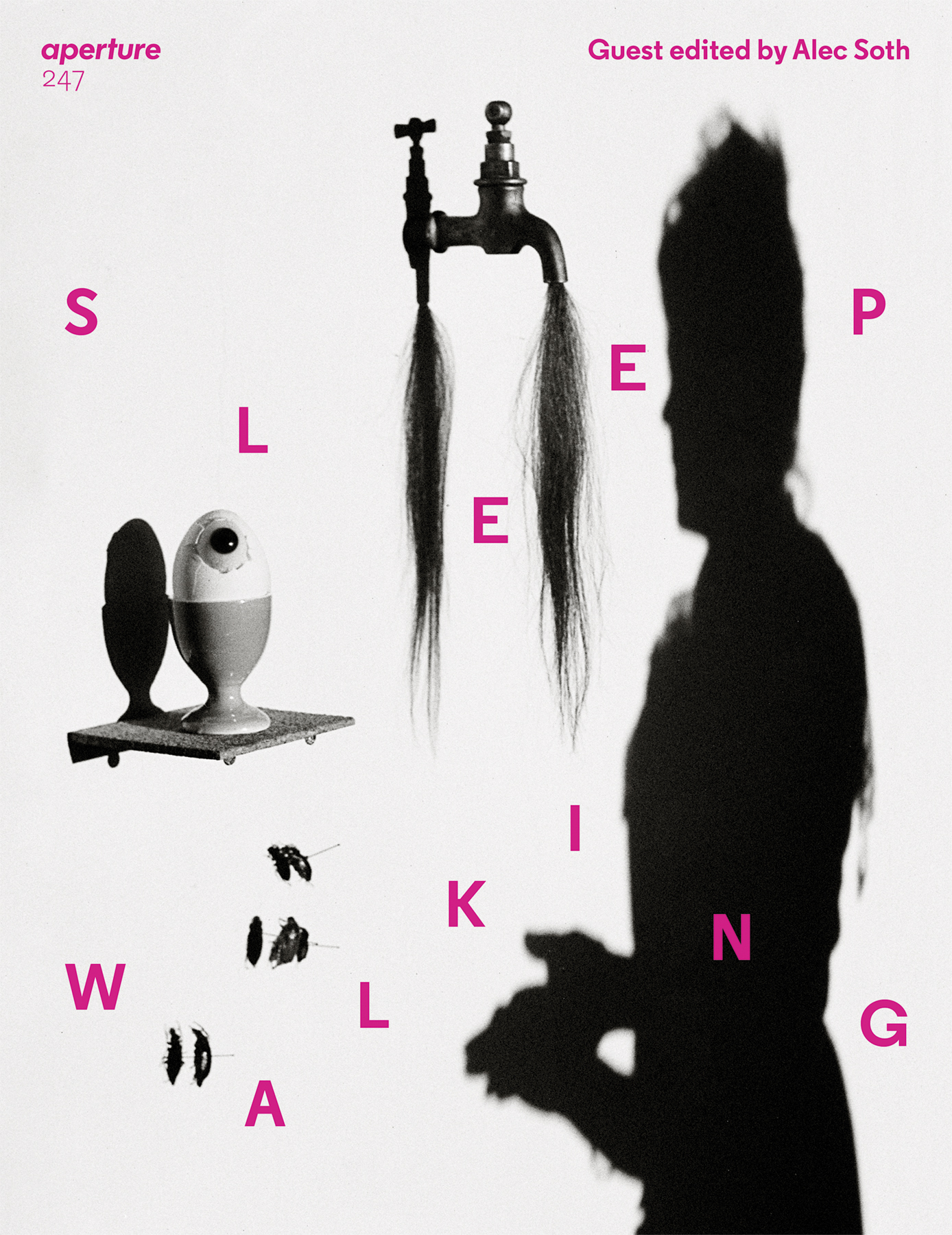

This article is published coinciding with Aperture, issue 247, “Sleepwalking,” guest edited by Alec Soth.