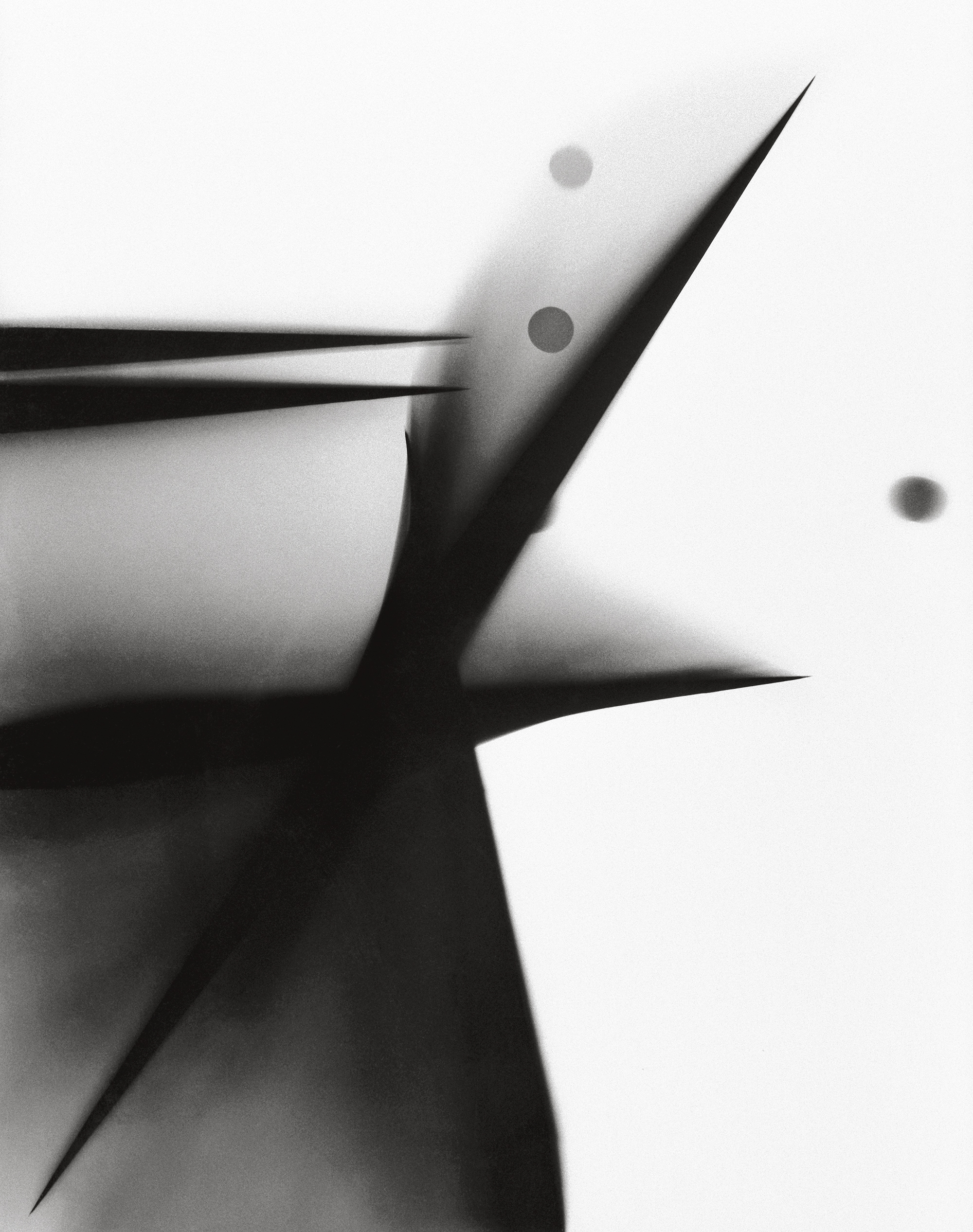

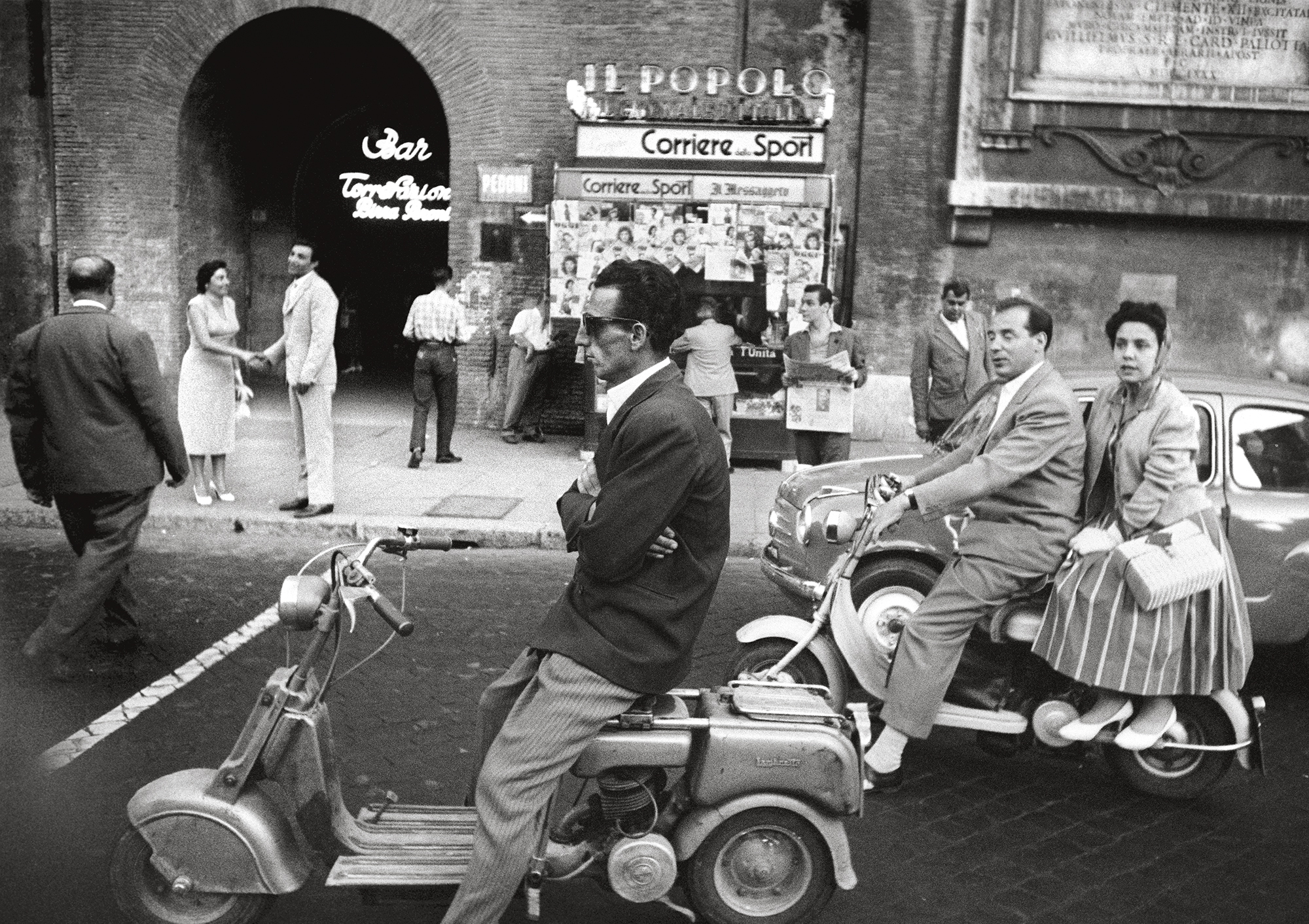

William Klein, Untitled #9, 1952

When writer Aaron Schuman first arrived at William Klein’s apartment, five stories above Paris’s rue de Médicis, he was ushered into Klein’s living room by his assistant. Klein, eighty-seven, had been up until four thirty in the morning the night before and was having a rest. After an hour or so of thumbing through this Aladdin’s cave of trophies and treasures, Schuman heard Klein stirring in the rooms at the back of the apartment. “By the tone of his voice, I could tell that he had just woken up, and was reluctant to join me,” Schuman said. “His assistant pleaded, ‘But he’s come all the way from England!’”

Finally, Klein entered the room, eyes wide and shining. This would be the first of two visits with Klein for this interview, which touches on his now-classic books on cities, including his hometown in Life Is Good & Good for You in New York: Trance Witness Revels (1956), Rome (1958–59), Tokyo (1964), Moscow (1964), and Paris (2003), all alive with Klein’s signature kineticism; his 1960s fashion work for Alexander Liberman, the celebrated art director at Vogue. This was the era in which Klein turned to moving images, having just made his first film, Broadway by Light, in 1958: he would become known for his fashion-world satire Who Are You, Polly Maggoo? (1966), starring model Dorothy McGowan, and Muhammad Ali: The Greatest (1974), his cinema verité documentary on the fighter, among others. Recently, Klein has been revisiting some of his first experiments with still photography, abstractions from the early 1950s, some of which were exhibited at his London gallery last fall. In the conversation that ensues, he speaks about his remarkable career, now in its seventh decade, with the force and energy that define his photographs and films.

Aaron Schuman: First, how old were you when you knew you wanted to be an artist?

William Klein: I was pretty young—around ten or eleven. I guess I always had this fantasy that I could be an artist. But it was a long time ago; I forget. Do you see the cat? [Points to solar-powered toy cat by the window wagging its tail like a metronome.] You see what it’s doing?

Schuman: It’s wagging its tail.

Klein: Why? Because there’s light. There’s a little solar panel in it. A Japanese editor brought it for me. Every time he comes, he brings another cat. I asked him, “How come you bring all these cats?” and he said, “We love cats.” I said, “Everybody loves cats, but they don’t always bring me cats.”

Schuman: When’s the last time you were in Japan?

Klein: I haven’t been there for twenty-five years. You know my book on Tokyo?

Schuman: Yes.

Klein: Well, there was a group of dancers that became butoh [the dance theater group], and they wanted me to photograph them in the studio, but I said, “No, let’s go out in the street.” So we went out in Ginza, down little streets and everything. There’s one picture I took of this crazy painter—the boxing painter, [Ushio] Shinohara. He lives in Brooklyn now; they did a film on him, Cutie and the Boxer (2013). It was up for an Oscar. Anyway, his wife did most of the talking, and I said “How come you speak such good English, and he can barely say hello?” And she said, “Well, you know—artists are stupid. And he’s stupid” [laughs]. But he’s a great artist.

Schuman: Do you think artists are stupid?

Klein: No, I don’t think so. It depends which one [laughs]. Ha, look at the cat. It’s going crazy.

Schuman: What first brought you to Paris?

Klein: The United States Army brought me to Paris. I came to Europe via boat, on the Queen something or other, and was sent to Germany during the occupation. Then I was discharged in Paris. I had gotten into the army at the end of the war, and since I had no knowledge of horses or radio transmissions, I was designated as a radio operator on horseback in Fort Riley, Kansas. After the war, the Americans thought they would be fighting the Japanese in Burma, and so I was trained to be a radio operator on horseback. I got out of college at eighteen and thought that I would have a cushy job in an office, but instead I was doing twenty-five-mile hikes.

Schuman: And why did you stay in Paris?

Klein: I met a French girl and we got married. I thought it was better to live in Paris than in New York. Look at that nice cat I got from the Japanese. I see that fucking cat wagging its tail like a maniac. I asked the Japanese editor, “How long will it continue to wag its tail?” and he said, “Always.” I said, “Perpetual motion doesn’t exist!” My wife became a painter in the last five years before she died, and I really like what went on in her head. She would be painting by the window, and I’d leave in the morning, and in the evening I would come back and there would be a painting [laughs]. But she never went to exhibitions or was worried about exhibiting her work. She was a real primitive.

Schuman: You yourself started out as a painter.

Klein: Yeah, as a kid I took courses in high school—Art 201 or whatever—and in college also. When I first came to Paris, I worked in the studio of Fernand Léger. He kept saying to us, “Fuck the galleries. Fuck the collectors. This is not your problem. Your problem is to be part of the city.” At that time, the walls of Paris were covered with these big paintings that the hacks working for the movie industry would paint—scenes from the films. You’d see these big paintings of a scene in a movie, and Léger would say, “These guys are more interesting than the stuff you see in galleries, that you want to imitate and develop in order to seduce collectors. All that’s bullshit. Do what the painters did in the Quattrocento—work with murals and architects.”

Then, in 1952, I had a show in Milan in which I exhibited abstract mural paintings, and an avant-garde architect saw the show. He had developed a space divider in a big apartment in Milan, and he said, “I have these panels that turn and can be moved on rails to cover a wall or divide a space.” He asked me if I would be interested in painting these panels on both sides, so I did. Then I began to photograph them, and since they were on rails, they could turn and move.

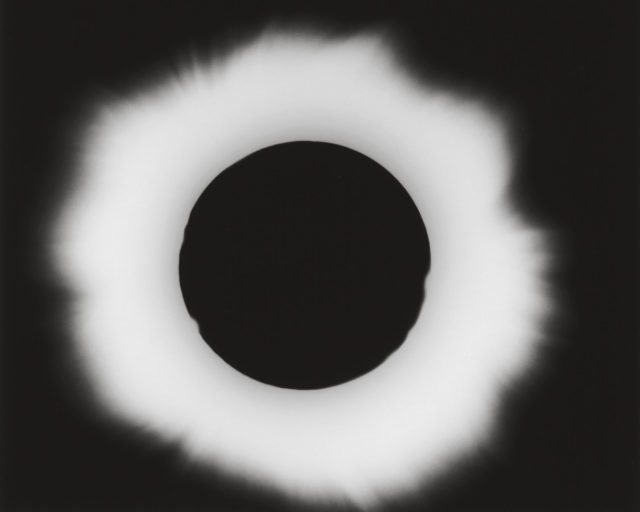

While I was photographing the paintings, I had somebody turn them. I was using long exposures because there was little light, and these geometric abstract forms that I had painted began to blur. I thought these hard-edged geometrical forms that I was using became different and more interesting with blur, which was a photographic plus and got me interested in photography. I saw that this was a way in which photography could direct a change in the use of geometrical abstract forms. Then I realized that I didn’t need panels with abstract forms painted on them—I could do it in a darkroom, and so that’s what I did. At that time, I felt that photography was leading the way. By varying the use of graphic forms, and using relatively long exposures to give variation to the forms I photographed, blur became part of my arsenal of graphic techniques.

Schuman: You recently published a new book—which was released in conjunction with a show you had at HackelBury Fine Art in London a few months ago—titled William Klein: Black and Light (2015). It’s based on a maquette for a book that you made of this work in 1952, yes?

Klein: Yeah, it was the first book I ever did—the maquette is over there somewhere. You know Kate Stevens [director of HackelBury Fine Art]? I call her Krazy Kate, like Krazy Kat. Have you seen the old Krazy Kats?

Schuman: Yeah, the comic strip.

Klein: Yeah, the comic strip. But in the old days it was in black and white, and really profound. The cat’s main object in life was to throw a brick at the cop’s head. Anyway, Krazy Kate is what I call her. She’s very determined. Somebody said to me, “Listen, whatever Kate asks you to do, say yes; otherwise she’ll drive you crazy.” So she came to my studio several times, looked in boxes of all sorts, and for some reason she thought that the Black and Light work wasn’t well-known enough, so she decided to make a show out of it. I didn’t really think that was such a good idea. I did these things in a certain manual way, and I have the impression that people with computers do something similar now and wouldn’t be interested in stuff I did sixty years ago. So initially I was against the show, but I remembered that my friend told me to always say yes to Kate. And the show was great. I was kind of surprised by it, and the things that happened leading up to that work I have a kind of nostalgia for.

Schuman: You seem to be nostalgic for things specifically from your early childhood as well—Krazy Kat and so on.

Klein: Well, there were good things in America—Krazy Kat was one of them. In London we had afternoon tea with Kate Stevens, and I told her to look up Krazy Kat on the Internet. She did, and on her iPhone we got a concert of Shirley Temple. [Begins singing] “On the good ship, Lollipop, it’s a sweet trip to a candy shop, where bonbons play, on the road to Mandalay.” I added that Kipling line at the end. My mother decided that my sister would be the new Shirley Temple. In my film Who Are You, Polly Maggoo? the prince fantasizes about Polly, and one of the apparitions is Shirley Temple. So we had to find someone to sing Shirley Temple. Michel Legrand and I did the music, and at the time he was doing a record with Liza Minnelli, so we asked her. But she didn’t know Shirley Temple! She had a voice that could go with Shirley Temple, but she didn’t know Shirley Temple. I thought it was amazing, because Shirley Temple was the biggest star—she did ten or eleven films that were blockbusters. Her films came out, and my mother—who wasn’t a cinephile—would bring me and my sister to Radio City Music Hall to be inspired.

Schuman: Were you inspired?

Klein: Inspired? No, I hated Shirley Temple. We had to move three times because my sister was tap-dancing so much that the downstairs neighbors complained. But it was a nostalgic place to live, and be surrounded by my sister tap-dancing and the neighbors complaining.

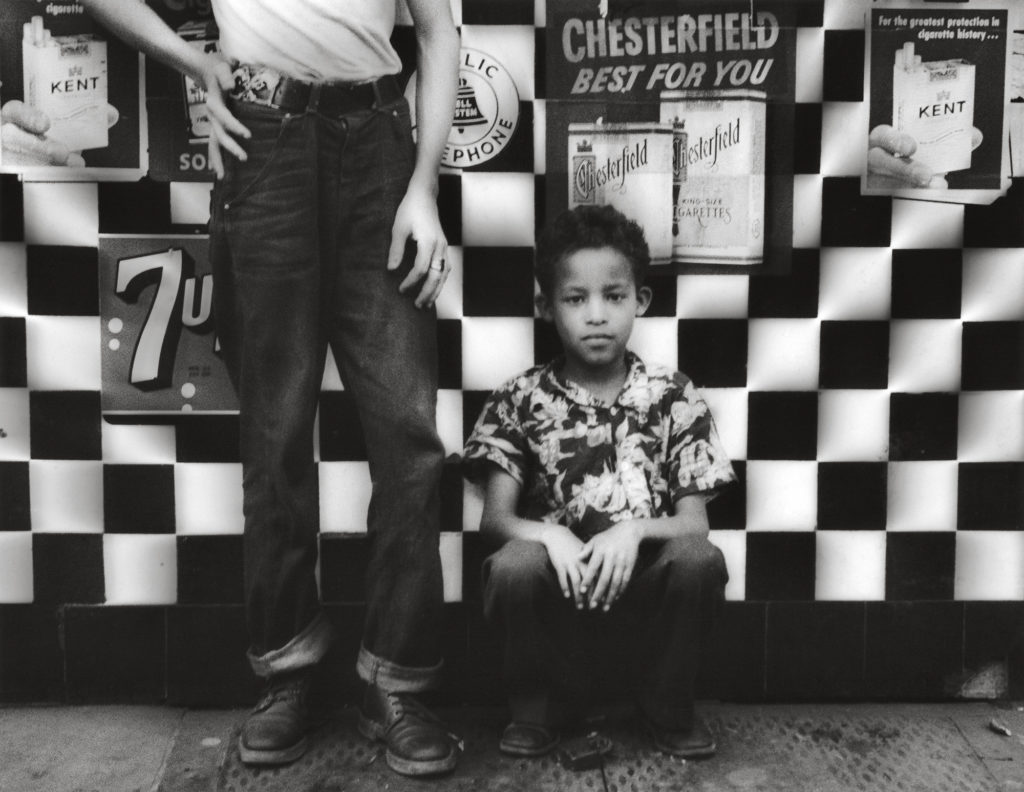

Schuman: Many of the most famous photographs from your first published book—Life Is Good & Good for You in New York: Trance Witness Revels—feature children: kids playing stickball, a boy sitting in front of a checkerboarded candy store, children blurred while mugging for the camera, a kid shoving a toy gun into the lens.

Klein: One time, Life asked well-known photographers to find the people that they had photographed two generations earlier, and they asked me to find the boy with the gun. But actually, when I took that photograph I was just walking down the street, I saw some kids playing cops and robbers, and I asked three of them to look tough, so it was a setup. But the idea of finding them again was crazy. I didn’t go along with it.

Schuman: Did those boys remind you of yourself as a kid?

Klein: I would try to be tough, and also I played cops and robbers. I dream a lot. Last night I was dreaming about a place where we lived, near the river, on 93rd Street. I would play with my sister on the rocks

near the water. That image has kept coming back recently.

Schuman: Do you dream in black and white or color?

Klein: Black and white, of course.

Schuman: What else do you dream about?

Klein: I dream about a million things. It’s incredible. I had a dream recently, and I still don’t know whether it was a dream or not. It was about New York. Jean-Luc Godard was there, it was a Saturday, and there was an art opening. The people there were very friendly, and Godard was so, so nice, and also friendly. He was exhibiting his paintings, and people were saying, “Oh Jean-Luc, you have to come to my studio—I have some nice paintings to show you.” And he would say, “Of course!” which is so little like him. It was so precise, and everybody was the way that they should be. It was Godard being a nice New Yorker. He’s a prick, actually; I know him pretty well.

Schuman: So how did you go from making abstract black-and-white images in the darkroom to taking photographs on the streets of New York?

Klein: Well, once I had the possibility of enlarging in a darkroom, I realized that the other photographs I’d been taking at the time were not as bad as all that. I was a primitive, and the photographs I was taking for myself were at the level of zero in terms of the evolution of photography. But once I had the opportunity to take the negatives and print them my way, I realized that I could use what I had learned—about graphic art, painting, and charcoal drawings, and so on—in my printing. So when I went back to New York, I had an idea of doing a book. I was twenty-four or twenty-five, something like that, and when you’re twenty-five you can do that sort of thing; if you decide to do it, you just do it. So I turned the bathroom in the hotel I was living in into a darkroom, and had access to a darkroom in my apartment. I washed the prints in the bathtub, and now these prints are considered “vintage prints”—they’re worth a lot of money.

Schuman: I was just looking through some of your old magazines, and saw that the first body of work you published in Vogue was selections from Black and Light.

Klein: Yeah, I was participating in a show called Salon des Réalités Nouvelles in Paris (1953), and Alexander Liberman—who was the art director of Vogue, and then became the art director for all of Condé Nast—left me a note asking me to come and see him. So I did, and he said, “How would you like to work for Vogue?” And I said, “Doing what?” and he said, “Well, we’ll see. You can be assistant art director or something.” We ended up deciding that I would do photographs, but I had no idea what kind of photographs I could do for Vogue.

I looked at the fashion magazines, and I was really convinced that I couldn’t do anything like what the fashion photographers were doing; I mean, I thought their technique was beyond my reach. But when I looked more closely, I thought they weren’t so hot as all that, and the only photographers that impressed me were [Irving] Penn and [Richard] Avedon. The rest were just part of a system, and the more I looked at their photographs, the more I felt that there weren’t any really interesting ideas behind them.

Schuman: Before shooting any fashion photographs for the magazine, you also published a series called “Mondrian Real Life: Zeeland Farms” in Vogue in 1954.

Klein: Yes, my wife inherited a house on the Dutch and Belgian frontier. One day we took our car and drove to the nearby island of Walcheren, and I saw these barns. They reminded me a little bit of the Dutch houses in Pennsylvania, and I learned that Mondrian had lived there during World War I. I thought that there must be some relationship between what he saw there and what he was doing later, so I photographed them. Then, when I met with Liberman again, he asked to see some of the stuff that I was doing, and when he saw those photographs he decided to publish a little portfolio of them in Vogue, which was unusual because it was a fashion magazine. But you know, fashion magazines at that time were the monthly dose of culture that women would get—theater, painting, exhibitions of all kinds—so those photographs fit in with the philosophy of Liberman.

Schuman: Did you enjoy working for such magazines at that time, when they had an important cultural influence as well as being about fashion?

Klein: Why not? It was a way of making a living. The only things that were salable or publishable at the time were fashion photographs.

Schuman: Was that a concern of yours?

Klein: It wasn’t a problem, just an observation I had to make. I thought that the other photographs that I was doing—the abstract photographs, the realistic photographs, the New York photographs, and so on—were more interesting. But nobody else was really interested in them.

Schuman: Were you frustrated by the fact that people were more interested in your fashion photography than in your art or street photography?

Klein: I thought it was kind of bullshit photographing a dress, because I couldn’t care less. I was interested in photography and in photographic ideas. When I would do a session of fashion photographs my wife would ask, “What was the fashion like?” and I would say, “I have no idea.” I really had no knowledge. It was my fault because there were things going on in fashion photography—people like Yousuf Karsh, Erwin Blumenfeld, and other interesting photographers with a lot of culture. But I had no idea of the progression of fashion in the twentieth century. I did a film later on—Mode en France (1984)—and learned that the progression of the way women dressed, and the attitude of the designers, was also a reflection of what role women played in society. At the beginning of the twentieth century, women were dressed in fortresses; they were not accessible, and the dresses and outfits were stiff and impossible to open up. Then, people like Paul Poiret and especially Coco Chanel liberated the way women put on clothes. Chanel had women wear sweaters, and Poiret took away the stiffness. But I knew nothing about that at the time and didn’t put it into perspective; nobody around me was interested in that. When I took fashion photographs, it was around the time that Dior made his so-called revolution. But when I look back, I realize that it was bullshit, because the real inventors were people like Chanel, who let women wear men’s jackets and sweaters and so on.

Schuman: You mentioned your 1984 film, Mode en France, but you started making films much earlier, in the 1950s—what initially inspired you to start making films?

Klein: Well, you know, once I had done books and told stories with my photographs, movies were an obvious development. In Life Is Good & Good for You in New York: Trance Witness Revels, the layout and turning of the pages was, for me, a movie. Instead of stopping at the level of pseudo-movie, I thought, Why not do a real movie? So photography and variations of graphic work led me to movies as well.

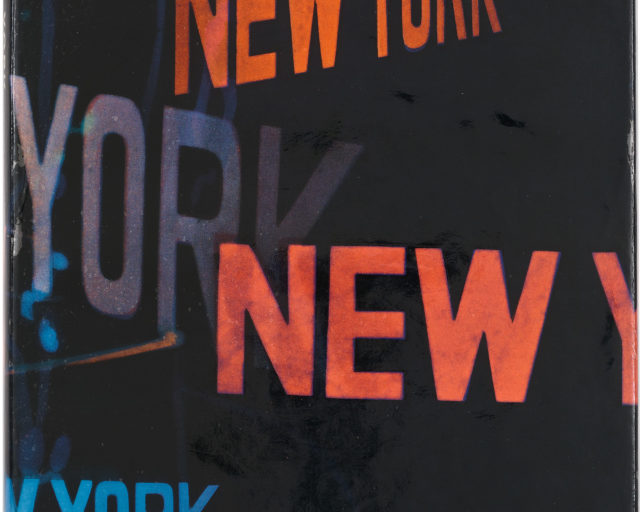

Schuman: Like Black and Light, your first film—Broadway by Light—was quite an abstract, graphic film.

Klein: Yes, the New York photographs were criticized initially because they presented a vision of New York and America that was very harsh, black and white, and grungy. So I thought the next step would be to do a movie; I could do the same thing, but with something as beautiful as Times Square and the incessant ballet of advertising. The first thing that people photograph or digest in New York is Broadway and Times Square—it’s the most beautiful thing in New York, and in America. But what is it, what are people actually seeing? They are seeing the spectacle of advertising; it’s buy this, buy that. It’s beautiful, but it’s made up of sales pitches, and people are fascinated and seduced by advertising. That was American art at the time. And Broadway by Light was a celebration of this whole process of selling—of taking people by the lapels of their suits and saying, “Buy this! Buy that!” and being immersed in the graphic world of advertising. The beginning of Broadway by Light is a big close-up of the bottle cap of the Pepsi-Cola sign, which is like the sun—it comes up, fills the screen, and then you go on to the other advertisements. That was the first film that I did, and people were struck by it.

When I was at Léger’s studio, there were three young American painters working there—Ellsworth Kelly, Jack Youngerman, and me. Ellsworth was very struck by Broadway by Light, and he arranged to have screenings of the film in New York, so all of these people from the art world saw the film and realized that what they were seeing were transpositions of this hard sell, which was Times Square and Broadway. Also, in those days there was a culture of short films, many of which were produced by a guy called Anatole Dauman. He would have filmmakers like Chris Marker, François Reichenbach, and so on making short films, and there was a festival in the city of Tours—the International Festival of Short Films—where everybody would go and see them. Broadway by Light won first prize one year, and later on I also won first prize with Cassius the Great, which was about Cassius Clay preparing for the championship fight against Sonny Liston in 1964, and eventually became the feature film Muhammad Ali: The Greatest.

Schuman: Were you a big fan of boxing?

Klein: Yeah, the sport I took at university was boxing, and then I boxed in the army. I was the middle- weight for my regiment, and we had competitions between regiments. If I boxed on a Friday night, I would have the weekend off, so instead of being AWOL, I would have a pass to spend two days going to the local cities and finding girls. But there were boxers in my regiment who had no idea about boxing as a science. They were farmers or steelworkers, and all they knew was fighting in the streets. I remember that there was a boxer who wasn’t very big, but he was powerful. He would go into the ring and just want to hit the other guy—and when he did, the fight was over.

Schuman: What did you see in Cassius Clay that made you want to make a film about him?

Klein: I didn’t understand anything about Cassius Clay when I started making the film. What I knew about Cassius was what I read in the white press. They all thought that he was a clown and that his fights were rigged. He was taken up by a bunch of sportsmen called the Louisville Syndicate. They bought the rights to Cassius Clay as they would a racehorse. They were from Louisville and always dreamt about winning the Kentucky Derby, so they saw a good investment in this young guy who had won the Olympic title. So they got the rights to him, paid for his training, and arranged his first fights. So most people thought that his fights were rigged, and that the career of Cassius Clay was completely manipulated. It was only much later that people realized how good he was, and what a rough fighter he really was, because he demonstrated that he could take a punch. He took too many punches, actually, and said, “I’m the greatest of all time!” before he could prove it. In Miami in 1964 he fought Sonny Liston, who everybody thought would wipe him out. But Sonny Liston had no idea how fast a fighter Ali was; he couldn’t hit him, and after six or seven rounds Liston gave up.

Schuman: Why did you decide to move from making short, abstract films to documentaries, and then to feature-length narrative films?

Klein: Well, most of the filmmakers that became the vanguard of French moviemaking, and eventually became icons, showed their short films at Tours and then went on to make feature films. The short films were all more or less abstract; they told a story, but the story was mostly about movies. So the festival was a place where film ideas were planted, which eventually became French as well as Polish, German, and Italian cinema. And how could you make a feature film without a story?

Schuman: In 1969, you made a satirical superhero film called Mister Freedom, which, like Broadway by Light, was critical of American commercialism, but in a very different way.

Klein: Yes, superheroes are a common language of movies nowadays, but that didn’t exist at that time. You would see all the superheroes in comic strips, but the thing the struck me was that you never knew who Superman, or the Hulk, or Spider-Man was working for. I mean, they were out for the destruction of evil and the promotion of good, but who was financing these guys—who was behind them, and who were they working for? So I had the idea to do a film about a superhero called Mister Freedom, who was pushing American freedom, but treated France like a third-world country. Mister Freedom was like Captain America, but the hero of God knows what—he was selling the American dream, but the American dream in the hands of Mister Freedom was actually a nightmare. At one point in Mister Freedom you see the elevator of the Freedom Building, and each floor is a supernational company—steel, or oil, or Unilever, and so on—and it’s clear that Mister Freedom is working for all the supercompanies of domination and oppression.

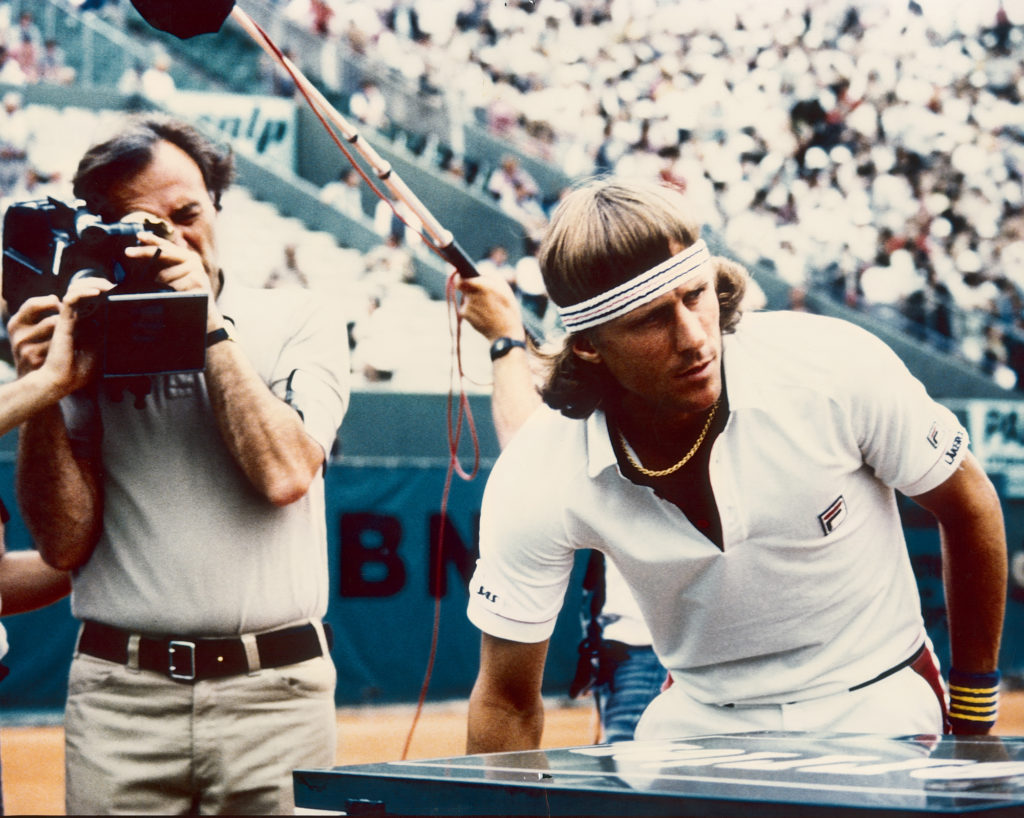

Schuman: You also made a sports documentary in 1981 about the French Open: The French.

Klein: Yes, I used to play a lot of tennis—every day in the summertime, and two times a week all year around. I love to play; I love to hit the ball; I love the idea of geometry, and placement, and everything else that makes tennis great. Also, I was a groupie of heroes like Björn Borg, John McEnroe, and so on, so when I was asked to do a film on Roland Garros I thought that it would be a good opportunity to get to know my tennis heroes, and eventually become friends with some of the people I admired. But it didn’t really work out that way.

I never got to be buddies with Borg or McEnroe, and a lot of these players were pretty stupid—Jimmy Connors’s idea of participating in the movie was to drop his pants and simulate jerking off. There were only two or three guys who I got on with, people like Yannick Noah and a few others, who understood that I was trying to tell the story of what was going on in the world of tennis. But everybody in a tournament is out to make his mark, accumulate points, and progress, so they had no time for philosophizing about tennis and the role that they were playing. But I had fun.

Schuman: Do you see any parallels between great sportsmen and great artists?

Klein: They are superheroes. Borg at one point was unbeatable. I remember there was an advertising poster for JVC with Borg jumping up and hitting a backhand; he was so perfect and beautiful. So these guys—Borg, Muhammad Ali—they knocked me out, and I learned a lot from them.

Schuman: What are you working on now?

Klein: I wrote a film scenario about a year ago that I’m trying to get produced, and I just published a photography book, Brooklyn + Klein (2015). For me, having grown up in Manhattan, Brooklyn was always the pits; nobody used to care about Brooklyn. The only thing I remember is that when I was growing up, every time I met a girl at a dance in college or wherever, she would live in Brooklyn and we would have to take the subway for an hour. But Brooklyn was really a distant suburb. Nowadays, it’s very chic, and everybody wants to live in Brooklyn—even Hillary Clinton has her office in Brooklyn.

Schuman: Why did you choose to make a book about Brooklyn today?

Klein: I had a contact at Sony—who is now making digital still cameras—and they wanted to commission a project. I was trying to think of a subject that wouldn’t be at the end of the world, so I hit upon Brooklyn. Also, I guess it has something to do with my obsession with New York. But I thought Brooklyn wasn’t what it’s cracked up to be. I still have that Manhattan point of view a little bit, and see it as a second-rate suburb.

Schuman: Did you find it interesting to photograph nevertheless?

Klein: I find everything interesting to photograph. For me it was always Hicksville and still is—even if Hillary Clinton does have her office there—so I wasn’t seduced by Brooklyn. But I loved going to Coney Island when I was a kid, and I still do. And there were things that happened in Brooklyn that I don’t think could happen anywhere else. One night we were watching a [minor league] doubleheader: the Brooklyn Cyclones against the Staten Island Yankees. Staten Island, can you imagine? How can they be Yankees? Anyhow, we were watching the doubleheader and a guy came over. He recognized me and said, “I’m a Czech rabbi. I came over to Brooklyn in 1980, and I remember the 1985 playoffs like it was yesterday. Do you remember that?”

And I said, “No, I don’t” [laughs]. And here’s this Czech rabbi reminiscing about the playoffs in 1985, and he said, “Do you want to see a Hasidic prayer session?” And I said, “Sure.” And this was at, like, midnight. So we went there, and they all had fur hats on; this was in August. And they said, “Okay, you can take photographs, but no faces.” Then after a while they relented and started coming over to me, saying, “Take a picture of that guy—he’s got an incredible face!” That was the weirdest evening I’ve had in a long time.

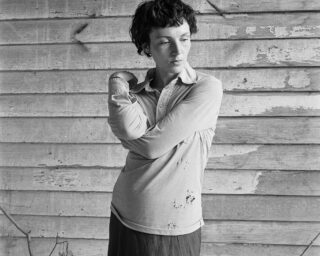

All photographs © William Klein and courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York, and HackelBury Fine Art, London

Schuman: What did you do last night?

Klein: David Lynch has a nightclub in Paris called Silencio, and he asks various people to show their work and talk about it. So they invited me to come, and I showed a couple of film excerpts: from Messiah (1999)—a film I made about Handel’s oratorio—and from my film about another messiah called Muhammad Ali, and several other sequences, as well as a mixture of different experiments in photography. I was there until very late last night.

Schuman: What’s it like to be an artist now?

Klein: I think it’s a good way of living and … [pause] I find it difficult to answer that question.

Schuman: What inspires you now?

Klein: The things I’ve done in the past lead to new things … and here I am, a hundred and fifty years old.

Schuman: How does it feel to be eighty-seven? When you look back on your life and reflect on your work, are you proud of what you’ve accomplished?

Klein: How does it feel to be eighty-seven? Not so good. But I’m satisfied with the different things I’ve done. And I want to continue as long as possible.

This article and photographs were originally published in Aperture, issue 220, “The Interview Issue,” and in Aperture Conversations: 1985 to the Present (Aperture, 2018).