Zanele Muholi's Faces & Phases

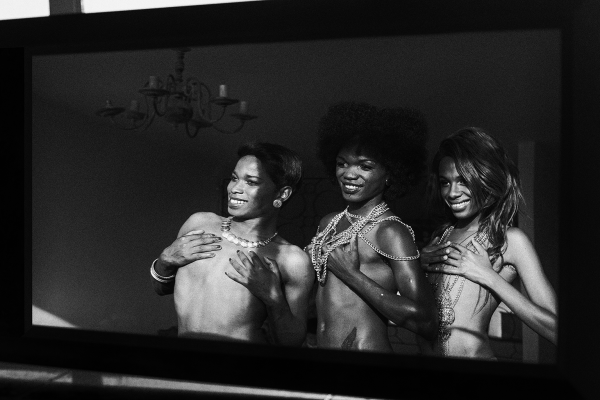

Eva Mofokeng, Somizy Sincwala, and Katiso Kgope, Parktown, 2014

For more than a decade, South African photographer Zanele Muholi created a visual record of black lesbians in her home country. Although South Africa legalized same-sex marriage in 2006, discrimination and violence against queer women remain widespread. In 2006, Muholi began her Faces and Phases project, an ambitious series of bold, undeniably powerful portraits of lesbians made against plain or patterned backgrounds—now numbering around three hundred—and often exhibited in tightly arranged grids. Faces and Phases is the subject of an extensive book, published by Steidl last fall, that forms a monumental chapter in Muholi’s mission to remedy black queer invisibility. Muholi’s work has been exhibited globally and she will have her first large-scale museum exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, Zanele Muholi: Isibonelo/Evidence, on May 1. Last November, Deborah Willis—author, curator, and prominent historian of photography—spoke via Skype with Muholi, who is based in Johannesburg, about photography and activism, her latest series Black Beauties, and her influences. This interview appeared in Issue 5 of the Aperture Photography App:click here to read more and download the app.

Deborah Willis: Let’s begin with Faces and Phases. When and where did this project begin?

Zanele Muholi: It started in 2006 and I dedicated it to a good friend of mine who died from HIV complications in 2007, at the age of twenty-five. I just realized that as black South Africans, especially lesbians, we don’t have much visual history that speaks to pressing issues, both current and also in the past. South Africa has the best constitution on the African continent and, dare I say, world—when it comes to recognizing LGBTI (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Intersex) persons and other sexual minorities. It is the only country on the continent that legalized same-sex marriage in 2006. I thought to myself that if you have remarkable women in America and around the globe, you equally have remarkable lesbian women in South Africa.

We should be counted and certainly counted on to write our own history and validate our existence. We should not feel that somebody owes us these liberties. So, it’s another way in which I personally claim my full citizenship as a South African photographer, as a South African female in this space, as a South African who identifies as black, and also as a lesbian. I’m basically saying we deserve recognition, respect, validation, and to have publications that mark and trace our existence.

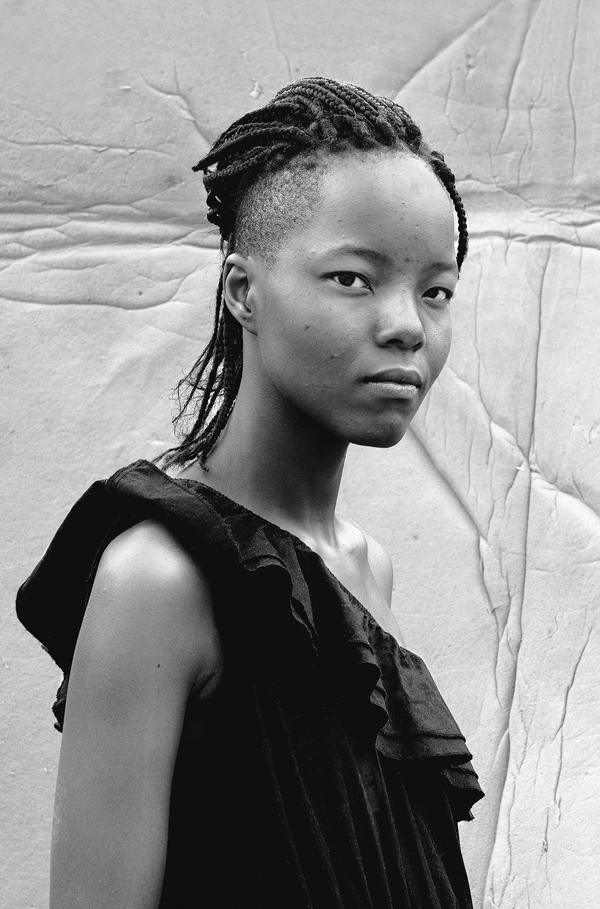

Lesedi Modise, Mafikeng, North West, 2010

DW: That’s a beautiful introduction to the project, which offers a wonderful way of reading bodies and faces and new identities. When’s the first time you remember seeing a photograph, or knowing a photograph, of a black lesbian in South Africa?

ZM: The early images I remember are black-and-white images of apartheid-era South Africa. Most were captured by male photographers like Ernest Cole or Alf Kumalo. Early images I saw depicted black women crying, images of pain, of struggle. Before black lesbian imagery clouded my mind, the first images I remember are of domestic workers, which were captured mainly by men. I looked at the work of David Goldblatt, who I regard as one of the forefathers of photography in South Africa, and the work of Jürgen Schadeberg. Those are some of the male photographers who captured apartheid South Africa.

I was born at the height of apartheid. I learned about South African women photographers very, very late. A friend gave me a book called Viewfinders: Black Women Photographers (1993), which was produced in America. I liked that book very much.

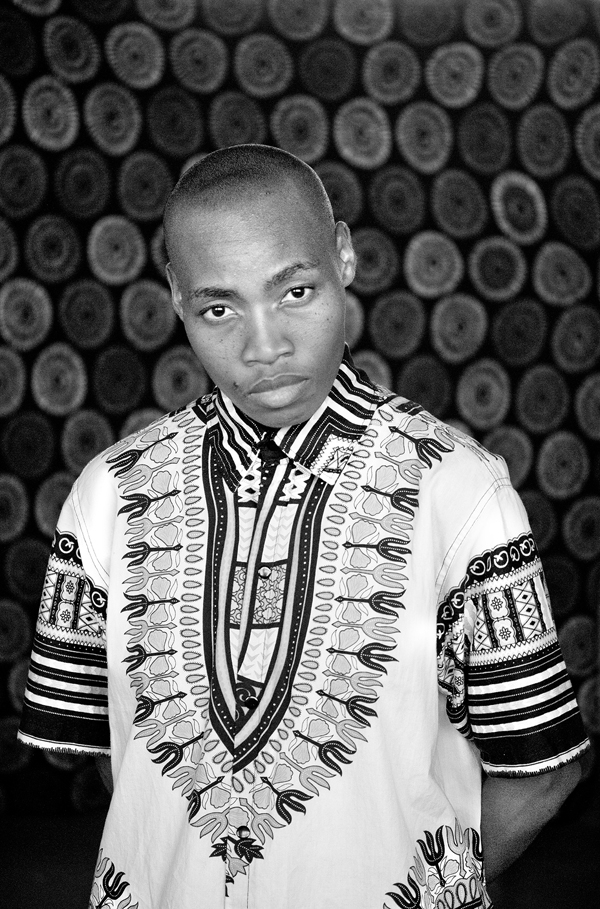

Tumi Nkopane, KwaThema, Springs, Johannesburg, 2010

DW: Viewfinders was written by the photographer Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe.

ZM: Yes, her book changed my life in so many ways. I just thought to myself that photography has to become a lifetime thing in which I deal with my own issues, my own personal issues. I quoted Joan E. Biren (JEB), an American photographer, in my thesis. Her work related to what I wanted to achieve, and it still means so much to me in ways that you won’t believe. You look at Biren’s images and you think that someone has done what I’m trying to capture now, except I’m doing it from a South African point of view.

I understood the South African struggle of being forcefully removed from your own space, a space you thought belonged to you, where women were regarded as working machines. My mom was a domestic worker and the images of domestic workers, and the images of women crying, struggling, with children on their backs, those became my daily consumption.

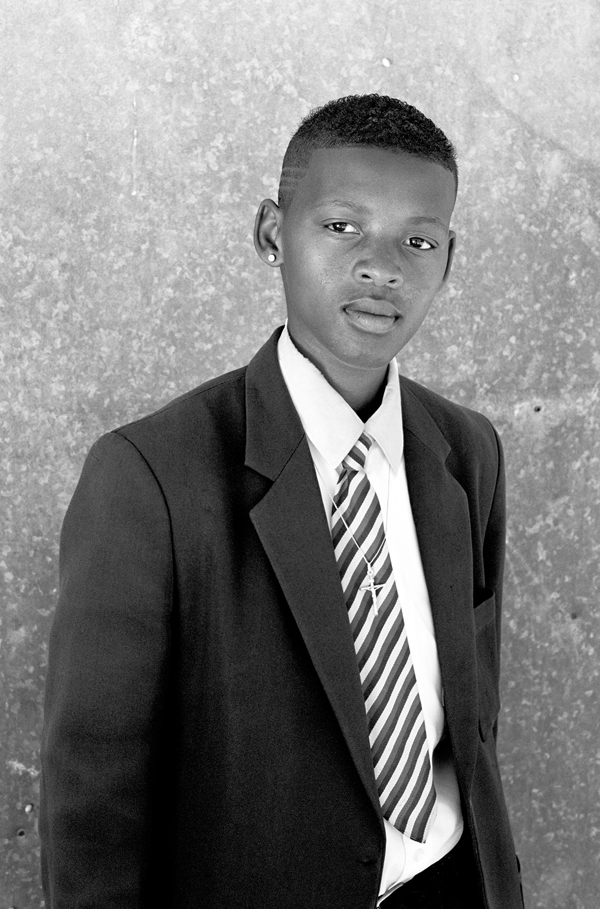

Teekay Khumalo, BB Section, Umlazi, Durban, 2012

DW: Did you start off by photographing your mother, early on?

ZM: I photographed my mom very, very late, around the time she started getting ill. It’s often very difficult for us to confront our own issues. I mention in my film Difficult Love (2010) that it’s a pity we don’t tend to look at ourselves and our immediate spaces and how the outside world becomes familiar and easier for us to deal with than our own personal issues. She had cancer of the liver, and she passed on in 2009. But I do have images that I took of her.

Yonela Nyumbeka, Makhaza, Khayelitsha, Cape Town, 2011

DW: How did she feel about the photographs?

ZM: She was always quite supportive of what I was trying to achieve, and I was out to my mom. I delayed the whole process of photographing her and missed her as a beautiful young woman. Looking at our family album, of images that were either dated, without the photographer’s name, or that had some strange names at the back, you think, Who has taken those images? What was their intention? Why are they not captured in this and that way?

The photograph that I eventually took later was of her wearing a church uniform. She was sick but allowed me to take that particular photograph. But I regret very much not having photographed her in her coffin. She looked so beautiful. But that meant negotiating with my family members, who didn’t understand the importance of documentation, so I let go of that photograph. In my imagination, I have this beautiful woman who did not look sick in her coffin.

Zukiswa Gaca, Grand Parade, Cape Town, 2011, Courtesy Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York

DW: Your photography has been described as work that “mourns and celebrates.” What do you think about such labeling?

ZM: It depends on the context. I’m reclaiming photography as a black female being. I’m calling myself a visual activist, whether I am included in a show or not, whether I am published or not. That’s my stance as a person, before anything else, before my sexuality and gender, because photography doesn’t have a gender.

Ernest Cole, for instance, captured the men in the mines. The mineworkers were humiliated to nothing, captured naked, discounted to nothing, nameless. He showed an unjust system that dehumanized workers. All we see, all we remember, are those black men and their bodies facing the wall. That was visual activism, but at that time people did not regard it as anything of that sort, even if people at that time were killed and forcibly removed. Today, lesbians in South Africa are brutally murdered. “Curative rape” is used on us. That forces me to redefine what visual activism is. If I were to reduce myself to the label “visual artist,” it would mean that what I’m doing is just for play, that our identities, as black female beings who are queer or are lesbian, is just art. Art needs to be political—or let me say that my art is political. It’s not for show. It’s not for play.