Meet the Press

At the Getty, all the news that’s fit to screen.

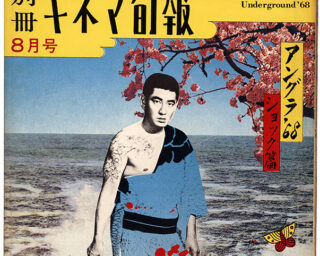

Donald R. Blumberg, Untitled, from the series Television Political Mosaics, 1968–69

Courtesy Donald R. and Grace Blumberg

Those seeking to unplug from the ongoing spectacle of Donald Trump’s cabinet appointments may find a grim kind of solace at the Getty Center’s exhibition Breaking News: Turning the Lens on Mass Media, where an incisive array of photography and video reminds that the Republican administrations of yesteryear were no picnic either. To wit, one of the Television Political Mosaics (1968–9) by Donald R. Blumberg, like televisions splayed out on a contact sheet, includes row after row of vintage talking heads from the vetting of Richard Nixon’s own unlovable cronies. Others in the series superimpose a faltering transmission of then-candidate Nixon’s profile into a black and gray miasma. Further Zen might come from Blumberg’s Television Abstractions (1968–9), a picture of a grid of sixteen TVs, all tuned to static. The white noise has never been worse, yet this exhibition offers critical insight for those who would turn today’s cameras on today’s screens.

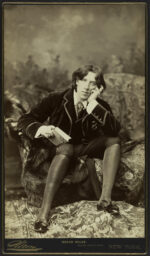

Catherine Opie, Debate, from the series Close to Home, 2004

© the artist and courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles

The grid—a format employed by half the artists here—is one way to wield the still photo against the moving image. Several works by Masao Mochizuki, for instance, compile dozens of thumbnails shot off television into single prints, from a story about quintuplets to a program on warplanes. The works effectively pause the media barrage, and set TV up for the kind of aesthetic scrutiny to which a photograph is more vulnerable. So too does the shock of the single drama tend to dissipate into deeper, disturbing patterns. In Alfredo Jaar’s Searching for Africa in LIFE (1996), a grid surveying the popular magazine reveals that in sixty years only five covers depict the continent. Jaar’s Untitled (Newsweek) (1995) is more damning. A cover lineup from 1994 comprises a timeline of the Rwandan Genocide; months passed before the magazine gave those mass murders a cover story—during which time O.J. Simpson had three.

Martha Rosler, First Lady (Pat Nixon), from the series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, ca. 1967–72

© and courtesy the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, NY

In concise but caustic subversions, the artists here zoom in, redact, and collage the supposed authority of the print photograph. Martha Rosler’s well-known series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home (1967–72), in which scenes from Vietnam haunt fashion shots of well-appointed American bedrooms and kitchens, is here twenty strong. Sarah Charlesworth, in April 20, 1978 (1978), redacted all but the mastheads and photographs on the front pages of national dailies, leaving the prioritizations of their editors as bare as, on the London Times, a lone paratrooper dropping into a blank page. Two decades later, Ron Jude reshot the lo-fi, largely reader-submitted photos of the Idaho Alpine Star, clipping hazy mementos from events of brief, forgotten importance.

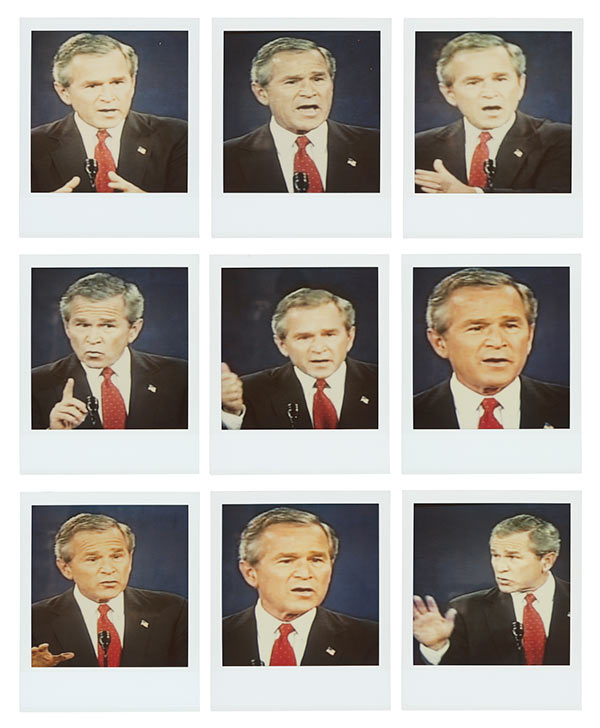

Robert Heinecken, TV Newswomen (Faith Daniels and Barbara Walters), 1986

© The Robert Heinecken Trust

Uniquely attuned to media’s aesthetic sleights of hand, other artists perform the work of specialists or consultants. Robert Heinecken finds a typology of newscaster emotion in T.V. Newswomen Corresponding (Faith and Barbara) (1986). His series A Case Study in Finding an Appropriate TV Newswoman (1984) couches a serious analysis of news media in what he calls a “docudrama,” fictionally framed as a commission for CBS, through which superimposed images of male and female morning show anchors become the target of the artist’s satirical physiognomy. One gets the sense that the networks actually do operate on a rubric of superficial qualities thought to convey sexuality and authority. As Heinecken observes, the men appear more often backed by world maps, the women by flowers.

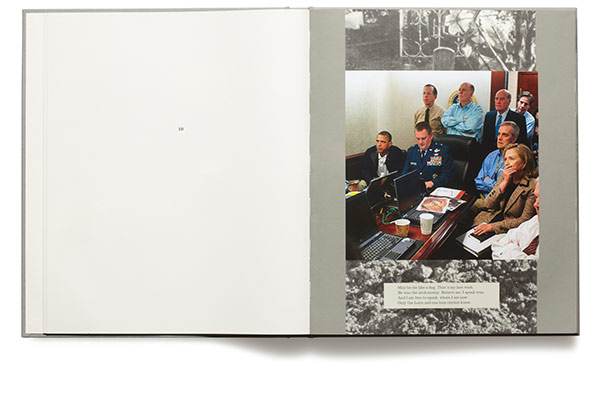

Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin, War Primer 2, Plate 10: President Barack Obama and Vice President Joe Biden, Secretary of Defense Robert Gates, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton along with members of the national security team, as they receive an update on the mission against Osama bin Laden in the Situation Room of the White House May 1, 2011, 2011

© and courtesy the artists and Lisson Gallery

The double-entendre of this exhibition’s title betrays its optimism, as if reiterating how reiterative these crises are might break the cycle’s hold. On the other hand, Breaking News might only update a pornographic resignation to media’s horror show. The most graphic images on view are also the most recent. Rosler reprised her Bringing the War Home in the mid-2000s, as America swapped its jungle fatigues for desert. In Broomberg & Chanarin’s War Primer 2 (2011), the pair pasted photographs from America’s antiterror exploits into copies of Bertolt Brecht’s 1955 War Primer, a bitter reprise of WW II-era press photos captioned with four-line epigrams. The sharp verticals of the burning World Trade Center rise out of a ruined German city; the bright red corpse of an Iraqi, hovered over by a US soldier’s camouflaged camera, blocks the blindfolded one of a Frenchman. Under this jarring revision, Brecht’s lilting quatrain feels defeated by having held true for fifty years: “And then to show you all / What came of him, we photographed the scene.” In our war of lens against lens, there’s no end in sight.

Breaking News: Turning the Lens on Mass Media is on view at the Getty Center, Los Angeles, through April 30, 2017.