The Mexican Fotonovela

How comic books illustrated with photographs became a great popular art form.

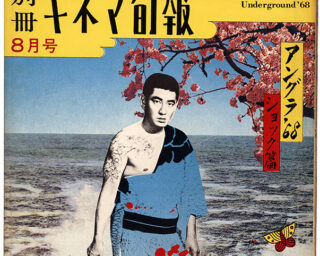

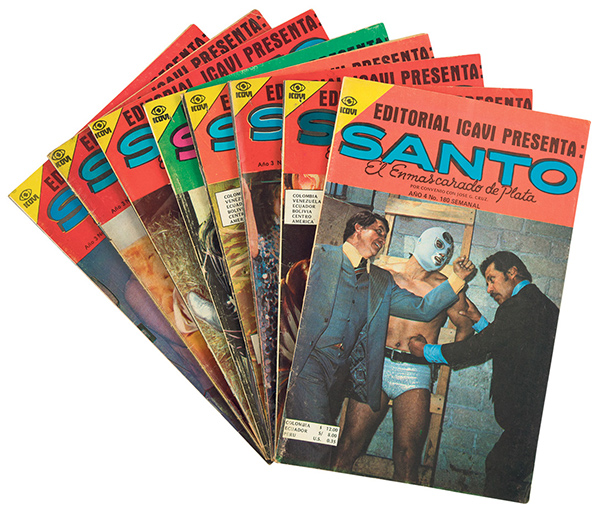

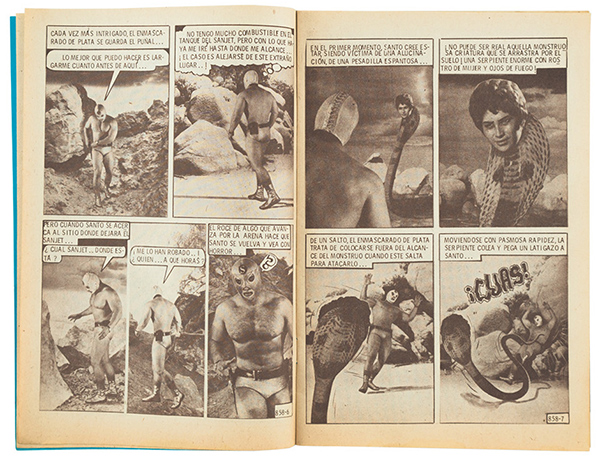

Santo: El Enmas Carado de Plata, Icavi, Columbia, n.d.

I’m not sure where I first saw fotonovelas, but it was probably when I was a little kid, during one of our family trips to Mexico to visit relatives. Fotonovelas are essentially comic books illustrated with photographs instead of drawings, operating somewhere between graphic novels, films, television, and pulp novels. Developed prior to the Second World War in Italy and France, they were originally made using film stills. They started to be produced in Latin America in the 1950s and were hugely popular in Mexico until the late 1980s, when VHS tapes of popular films and TV shows became readily available and affordable.

Santo: El Enmas Carado de Plata, Icavi, Columbia, n.d.

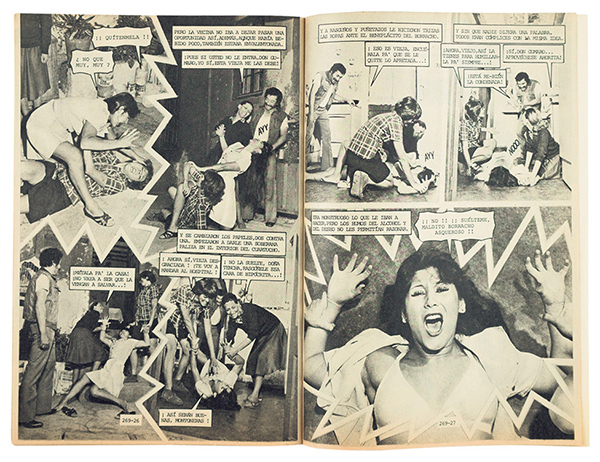

There are so many different forms of fotonovelas. There’s the classic telenovela type, the fotonovela rosa, which is the typical soap-opera Cinderella story: poor good girl meets rich, dashing guy (or a cad who treats her wrong). Then there are the fotonovelas rojas, which have more graphic depictions of sex and violence; among these are true-crime stories, which have dramatic reenactments of real cases. The sensationalist news magazine Alarma!, for which photographer Enrique Metinides often worked, even published a fotonovela edition called Casos de Alarma!. Finally, there are others that are essentially soft porn, although even these are careful to try to incorporate a moral element into the story. In fact, the fotonovela format has frequently been used for public-health and public-service announcements, and was even successfully drafted into AIDS-education efforts in Mexico.

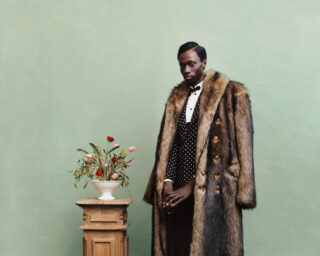

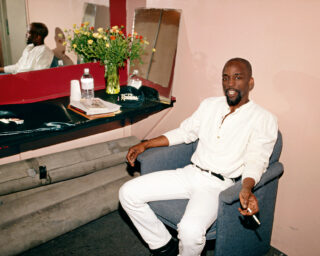

Valle de Lagrimas!, Publicaciones Llergo Mexico, 1977–1980

For kids in Mexico in the 1970s and early ’80s, El Santo, a character initially based on a real-life wrestler (but then dramatized to superhero proportions), was especially popular. Created in 1953, his was one of the first such stories that were photographed specifically with the creation of fotoaventuras, or adventure stories, in mind. This and other similar fotonovelas were aimed mostly at men and boys. They follow the adventures of various macho heroes—heroes with names like Kiling, or, of course, El Santo.

Valle de Lagrimas!, Publicaciones Llergo Mexico, 1977–1980

Fotonovelas are an obvious thing for me to collect because they fit my two primary interests: they’re photo-related, and they’re a popular art form. I started collecting them in the early 2000s, around the time I started my Telenovelas project, for which I photographed the real-life soap-opera stars of Mexico. I would pick up copies in flea markets and old bookstores. They were all over the place then. Similar to telenovelas, they deal with not only love and morality, but also class and race. They can be over the top, but they are almost always visually interesting—especially in the obvious yet creative ways they worked to get the “special effects” they needed, in a totally analog world.