In Berlin, a Retrospective of One of Germany’s Most Influential Photographers

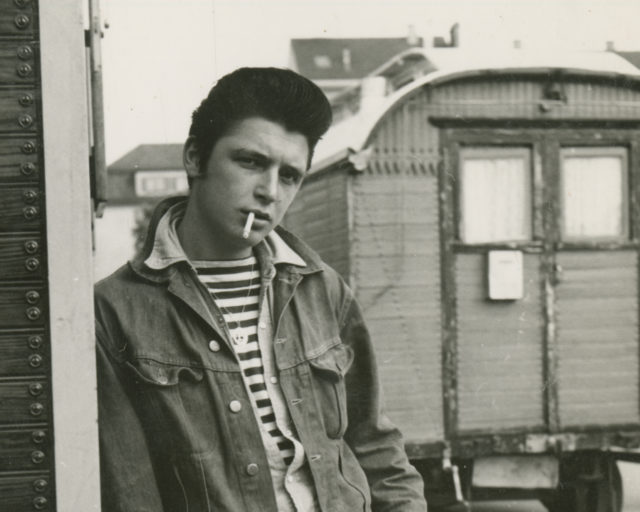

Michael Schmidt, Untitled, from the series Berlin-Kreuzberg. Stadtbilder (Cityscapes), 1981–82

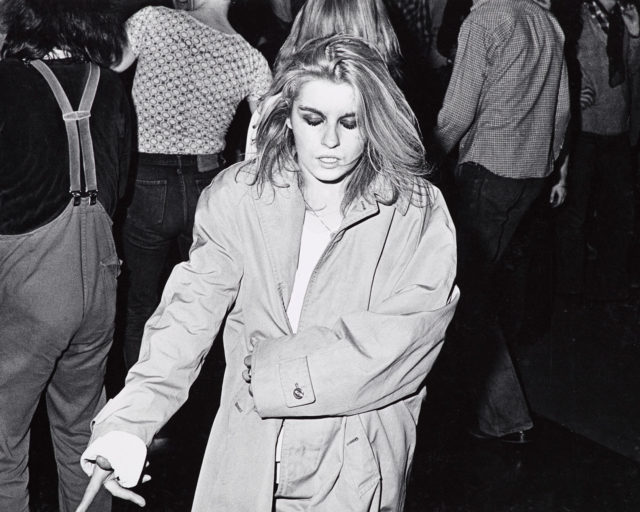

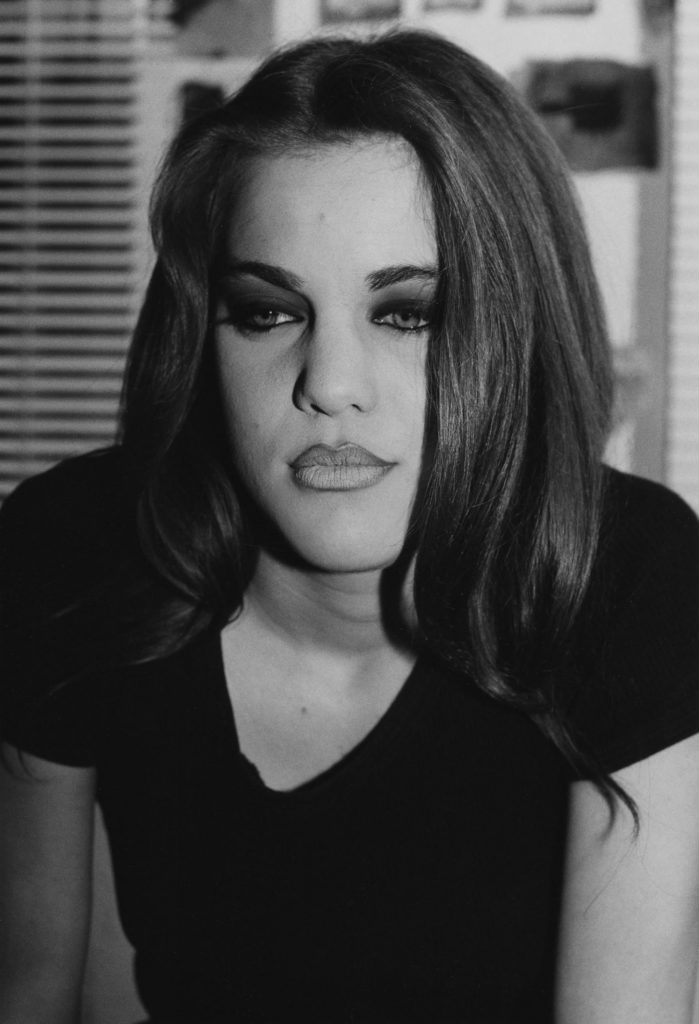

“Waffenruhe is a real ass-kicker,” the American artist Lewis Baltz wrote in a letter to Michael Schmidt and his wife Karin in 1987. According to Baltz, the series of haunting black-and-white photographs that Schmidt took in the years between 1985 and 1987, in proximity of the Berlin Wall and combined with still lifes and portraits of young adults, is a “masterpiece.” The work, which conveys a lingering hopelessness and feeling of entrapment, marked a turning point in Schmidt’s career. It also takes center stage in Schmidt’s retrospective Photographs 1965–2014, currently on view at the Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin, showcasing Schmidt’s five-decade-long career.

Born in Berlin in 1945, just a few months after the fall of the Nazi regime, Schmidt remained living in the city’s Kreuzberg district after the Berlin Wall was erected along its perimeter in 1961. And as with Waffenruhe, Schmidt dedicated a great deal of his work to the city—or more precisely, to West Berlin, its history, and its citizens. Schmidt began to photograph in the mid-1960s, when he was still working for the West Berlin police force as chief patrol officer. By the time he published his first book, Berlin Kreuzberg (1973)—which was commissioned by the Berlin senate and includes photos Schmidt had taken of his neighborhood throughout the four preceding years—he had quit his job in order to become a professional photographer. While he sold some of his pictures to photo agencies and received further funding from the city for socially engaged projects about working women in Kreuzberg, the disadvantaged, and the elderly, Schmidt struggled to depart from the conventions of documentary photography to develop a more distinctive artistic position.

Berlin Wedding (1976–78), another project on a Berlin district, would eventually become a breakthrough in that regard. While his Berlin Kreuzberg photos depicted everyday life in Kreuzberg, the streets of Wedding in Schmidt’s photos appear mostly deserted. These pictures are more rigorously composed and consistent in style. Arranged as a coherent series of urban scenes, they are paired with a group of portraits that show Wedding residents at work and in their apartments. The urban scenes of Berlin Wedding leave an almost eerie impression, yet the portraits seem somewhat comical in their reserved stiffness.

Unlike artists such as Ed Ruscha, Dan Graham, or Jeff Wall—who, by the 1960s, had begun to capture cityscapes and suburbia to critique the notion of objective documentary photography—Schmidt’s approach was less conceptually driven, less tongue-in-cheek and more concerned with technical and formal aspects. He never really broke with the documentary tradition but rather gave it a highly subjective and personal twist. His following series gained an essayistic quality verging on the poetic. Their aesthetic is closer—and Waffenruhe is a prime example of this—to that of the topographic ventures of John Gossage and Lewis Baltz. (Schmidt became friends with the two artists after he invited them to take part in an exhibition at Werkstatt für Photographie, a photography workshop at the adult education center in Kreuzberg, which he had founded in 1976.)

In the following years, Schmidt continued to present his work both in books and exhibitions. After Waffenruhe (and the reunification of Germany in 1990), Schmidt, however, focused increasingly on subjects larger than Berlin, and he explored different modes of photography and display. In Ein-heit (U-ni-ty) (1991–94), for example, which was first presented publicly in 1996 at the Museum of Modern Art, New York—the first solo show of a German photographer in several decades at the museum—Schmidt combined reproductions of found historical photographs with his own. Originally 163 photographs in total, the exhibition at Hamburger Bahnhof includes only a selection of the black-and-white images, all of identical size and arranged in a sequence without any indication of their origin or subject. Some are familiar, some enigmatic. Schmidt conceived of each as an ambiguous fragment of Germany’s history between 1933 and 1989. And so, the picture of a Nazi rally appears next to the portrait of a teenager wearing a baseball cap, next to a close-up of a bottle of liquid Diazepam, next to a portrait of Lenin, next to a cropped image from an East German Socialist Party publication.

Compared to the fixed sequence of a photobook, the presentation of Schmidt’s work in exhibitions has always given the artist the opportunity to try new variations and constellations. How far this site-specific aspect of his work will be realized throughout the next iterations of the exhibition remains to be seen. (After Berlin, the retrospective will travel to Paris, Madrid, and Vienna.) The show in Berlin provides a great occasion to dig deeper into Schmidt’s captivating work and related archival material. However, the retrospective format is a bit too formulaic and didactically implemented: the display of Schmidt’s lifework follows a rigid chronological order, reproducing the old trope of the artist finding himself and his “voice.” Consequently, the institutional effort to immortalize and cement Schmidt—an artist who checks all the boxes of privilege: straight, white, male—into the canon of art history becomes generic. This is something the other exhibition venues should consider balancing out, applying a more self-reflective curatorial stance and a vision that might better reflect Schmidt’s constant eagerness to overcome stale conventions.

Michael Schmidt – Retrospective: Photographs 1965–2014 is on view at Hamburger Banhof, Berlin, through January 17, 2021. All photographs © Stiftung für Fotografie and Medienkunst with Archiv Michael Schmidt.