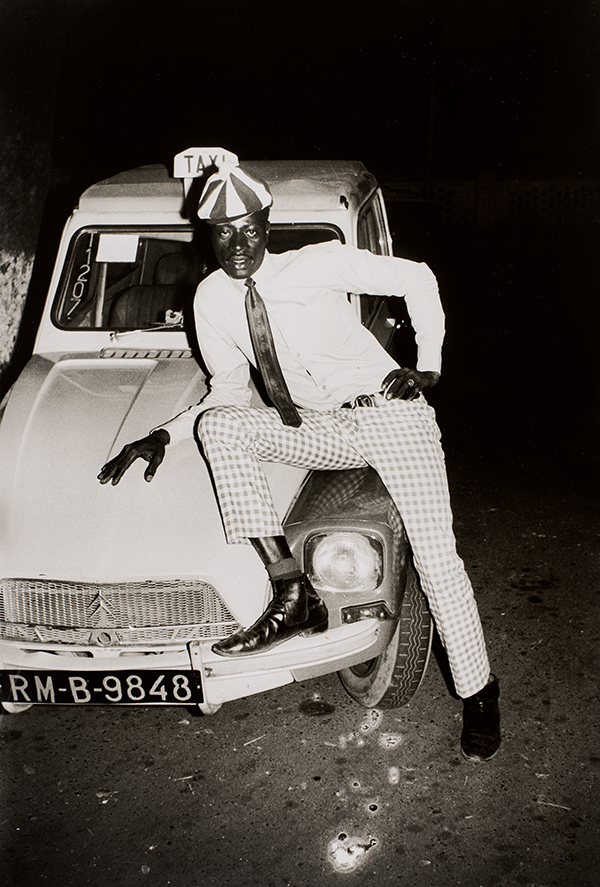

Malick Sidibé, Taximan avec voiture, 1970

I knew that Malick Sidibé was unwell. An interview seemed out of the question; I couldn’t bear the idea of dragging the great photographer on a long and exhausting journey down memory lane through his work and life. Not now that the illness was transforming his body and mind progressively every day. But, hoping to get closer to Malick’s roots, I wanted to return to Soloba, the village in southwest Mali where he was raised, to look for testimonies or written accounts of his career that could compensate for the silence imposed by his failing health. I wondered what I might find: Traces of the colonial administrator who was the first to discover the talents of the young Malick at the very beginning of the 1950s, when the French still controlled the region? Fragments of Malick’s life as a teenager in the streets of this village? Jazzy sounding voices and riffs of the kamele ngoni, a six-stringed harp?

We have a proverb in Bambara: “If you don’t know where you are going, seek to find where you come from.”

I went to see Malick’s son Mody to ask for his advice. Malick’s studio is in a house on the corner of a street like all the others in Bagadadji, a working-class district of Bamako. A big sign advertises the studio, and a group of young men (Malick’s sons and their friends) drink tea and talk. Sometimes you encounter a toubab, a white man, who has come to have his portrait taken or to visit the studio. Amongst this activity, Mody explained his father’s daily decline and confirmed that an interview would be impossible. I sensed his reserve and a will to protect his father’s privacy and old age from outsiders.

When I asked Mody whom to contact to accompany me to Soloba, he went toward the door of the studio and called out, “Yacou! Yacou!” A young man came inside. He said hello and listened to Mody, who asked in Bambara: “Can you take Chab to Wassoulou?” Mody said “to Wassoulou,” not “to Soloba.” The Wassoulou are the inner lands of Mali; Mody’s choice of term indicated to me how much the people of the Wassoulou love their land and still have a sense of belonging—not to a village, but to a place, a history. The great Wassoulou Empire once spanned from Bouré (now Mali) to Siguiri (now Guinea). A nineteenth-century empire whose towns have gone to dust. The walls of the palaces and the walls of the slums were made of the same temporary earth from the foundations up, so they disappeared brick after brick, clod after clod. The still standing traces of these formerly glorious cities are shea trees and a few scattered baobabs resisting the harsh stories of mankind.

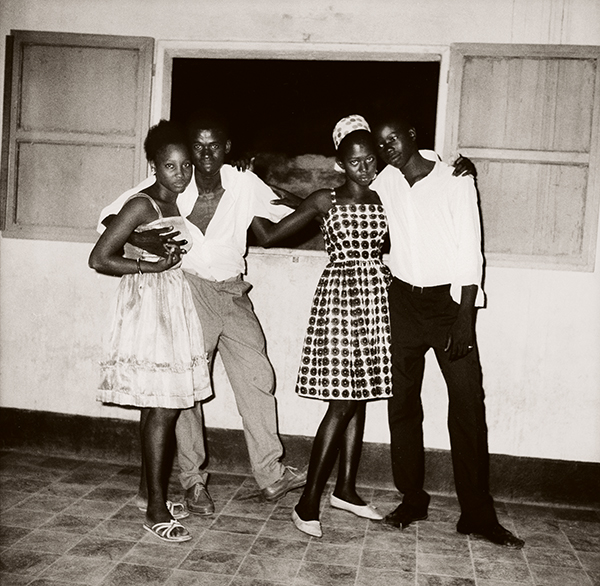

Courtesy Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Malick was born at the heart of the Wassoulou, where the ancient music of the Mandé people is connected, due to the slave trade, to the African American music of blues, soul, and funk. Sober and percussive, Wassoulou music juxtaposes the vocals of pentatonic female choruses with the equally pentatonic kamele ngoni. It mixes traditional and modern sounds, and is epitomized by the work of contemporary performers such as Coumba Sidibé, Nahawa Doumbia, Oumou Sangaré, and many other konos (birds). That generation sings about human suffering and heartache; they sing about women’s rights and the difficult realities of polygamy, which is commonplace in Mali. The warm enveloping voices of Soloman Sidibé (“the prince,” as his fans called him) and Aïchata Sidibé sang, “Chéri, viens plus près, chéri, approche toi … O diarabi, sensation. O diarabi, passion” (Sweet honey, be with me, honey, come closer).

As I drove, I listened to the Yanfolila FM radio station, called Radio Wassoulou. This radio has a very local program—local songs, advice to farmers about their crops, political information— but it does occasionally broadcast hip-hop or rap for its young listeners. At other times, the music program is retro, live from the 1960s. That morning, the Mercedes rolled along to the Temptations’ “Papa Was a Rollin’ Stone” and Sam Cooke’s “A Change Is Gonna Come,” until the radio waves slowly became blurred, and another station, broadcasting a song in praise of hunters, took over. But then the speaker was clear again, the coarse voice of Coumba Sidibé and her chorus in the background. The guitar notes mingled with those of the kamele ngoni, expanding the lyrical content of the song and bringing it close to the blues sound I heard just a bit ago in “A Change Is Gonna Come.” Did a confluence of sounds like these predestine Malick to become the photographer of Bamako’s 1960s soul nights? Otherwise, how could we explain the permanence of music and dance in the history and photographic work of the “eye of Bamako”?

To continue reading, buy Aperture Issue 224, “Sounds,”or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.